This story summary was translated from Portuguese. To read the original story in full, visit The Intercept Brasil. This is the third story in the Forest Thieves series by Rainforest Investigations Network Fellow Fernanda Wenzel.

During Bolsonaro’s term as president of Brazil, the Ministry of Environment opened up an area in the Amazon to loggers who knocked down 45,000 truckloads of trees.

From above, it looks like a serpent making its way through the woods. On the ground, the road carved out by tractors is wide enough for trucks to pass through. This is the entrance to the forest for chainsaw operators to cut down the most valuable tree species, such as the ipê and jatobá, whose cubic meters are sold at US$3,000 and US$1,500 on the international market, respectively. Once felled, the trees are brought to the trucks by a skidder, a machine with a large hook at the end perfect for pinching and dragging the huge logs.

Like termites opening trails through the forest, loggers have looted 45,000 trucks loaded with logs from a national public area located in the municipality of Lábrea, in southern Amazonas—a region that has become the epicenter of deforestation in the world's largest tropical forest. Put one after the other, the vehicles would form a queue of 450 kilometers, the equivalent of the distance between São Paulo and Curitiba. The looting did not happen with direct consent of the environmental authorities but gaps in regulation, disinterest, and irregularities meant the same bodies that should be protecting the environment gave their silent blessing.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The volume of trees removed from the public area is equivalent to five times the largest seizure of illegal wood ever made by Brazil’s Federal Police. In 2020, the year in which the largest amount of wood (30 percent or 200,000 cubic meters) was removed from the plot, the environmental agency of Amazonas, Ipaam, had already been warned of irregularities in the sustainable forest management plans of the region, which detail how many and which tree species can be cut down on a given property. The information was mentioned in a 2018 recommendation by the Federal Public Ministry, but while Ipaam ignored the measures proposed by the agency to stop the bleeding, the loggers increased the wound in the forest.

“In the meantime, practically all the volume that could be exploited in the fraudulent management plans has been used up and this wood, which is illegal, entered the timber circuit as if it were a legal product,” said Nilo D'Avila, senior researcher at the Greenpeace.

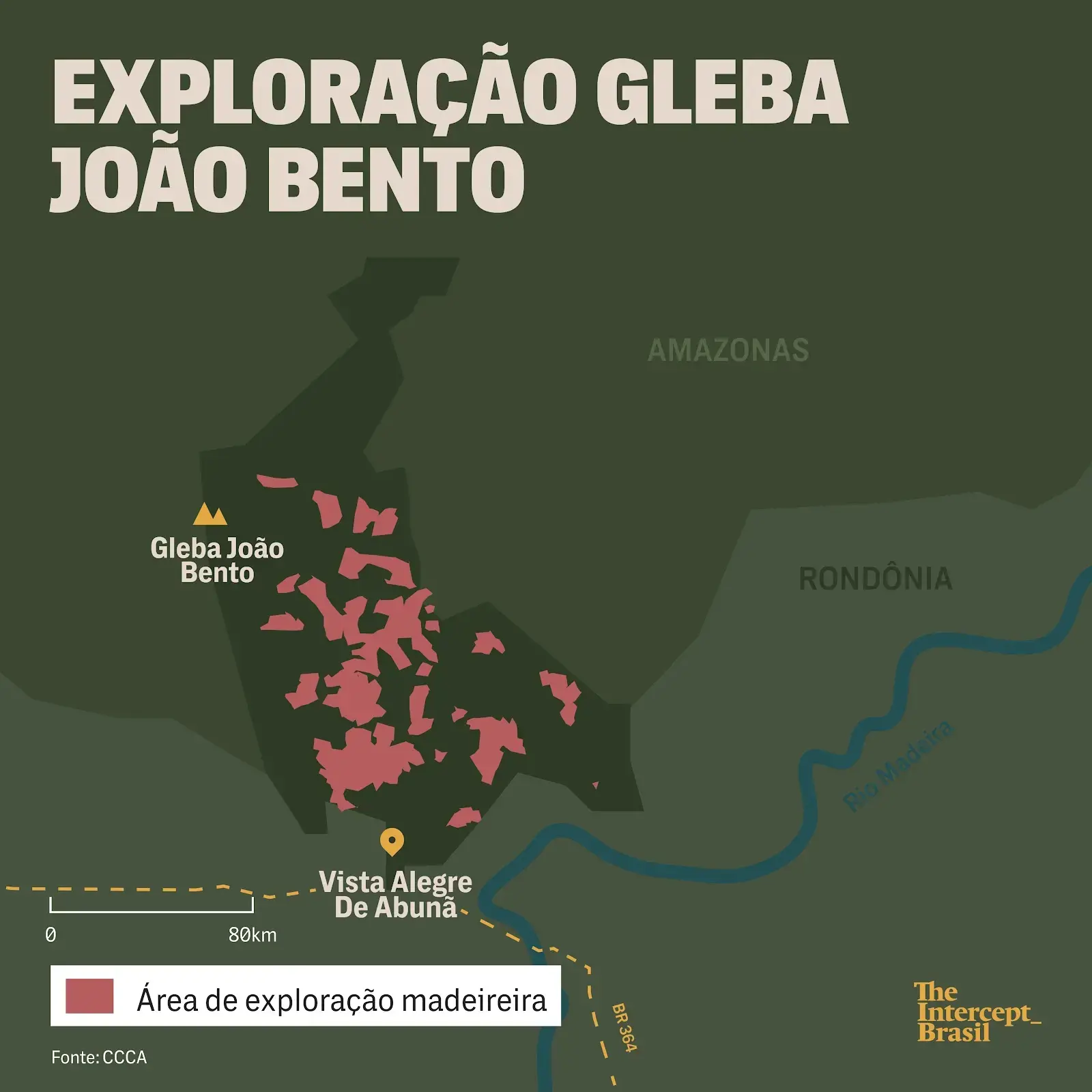

The size of two times the city of São Paulo, João Bento is a non-designated public area, or “gleba,” as public lands that have not been converted into Indigenous land, quilombola areas, conservation units, settlements, forest concessions, or private properties are called, and which have become the number one target for land grabbers, as the Intercept Brasil has shown in the first story in the Forest Thieves series.

The estimate of extraction in the public land is based on the scars left in the forest by loggers, visible on satellite imagery, and covers a period of nine years, from 2013 to 2021. The survey was carried out exclusively for the Intercept by the Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA)—an NGO that aims to hold companies contributing to global warming legally responsible—and was based on logging rates per hectare used in forest management plans in the region. In practice, the damage can be much greater, since in illegal extraction the volume exploited can be up to twice as high as that authorized by environmental agencies.

Hand in hand with land grabbing, the action of loggers has fed a deforestation machine that has already destroyed almost half of the 295,000 hectares of land, which is the last barrier before a vast block of protected areas, where there are even records of isolated Indigenous peoples—the most recent was discovered in 2021 in the Médio Purus Extractive Reserve .

“This region is home to the last large forest massifs we have in the Amazon, because the rest is already very fragmented,” said Antonio Oviedo, a researcher at the Instituto Socioambiental, or ISA.

You can read the full version of this story in Portuguese at The Intercept Brasil.