This story summary was translated from Portuguese. To read the original story in full, visit The Intercept Brasil. This is the second story in the Forest Thieves series by Rainforest Investigations Network Fellow Fernanda Wenzel. Our Rainforest Journalism Fund website is available in English, Spanish, bahasa Indonesia, French, and Portuguese.

It is August 15, a holiday in the Brazilian state of Pará, and dawn just broke in Novo Progresso. The city of 25,000 inhabitants, located on the edge of the BR-163 highway, is at a standstill. While the first customers of the day are entering and leaving the local gold trading stores, half a dozen men in the red light district are trying to recover from a restless night to start another day of work in the fiery heat of mines and forest clearings. In the comfort of their offices, brokers and engineers are busy finding ways to appropriate public lands from the state.

We are in the “center of agribusiness mining,” an area that “is being disputed at every inch by investors,” as one of the several Facebook profiles selling rural properties announces. The menu available to customers is varied. It includes areas with or without forest, inside or outside conservation units, with or without environmental fines, with or without gold. To take advantage of these options, the client just needs to be willing to forsake a land title.

“It is very rare to find a farm with a document in the region,” clarified Roberto, one of several brokers who profited from the appreciation of properties in southwest Pará after the construction of the BR-163 at the end of 2019.

With such a high demand, those who even sleep a wink run the risk of losing business.

“Not many options left, huh? Especially if you are looking for an area for farming [and in particular for soy],” Roberto said. “Here it is in a way that when three, four days pass, the owner is already selling.”

This real estate boom has resulted in a new wave of land grabbing and deforestation, which mainly targets non-allocated public lands: parcels belonging to federal or state governments that have not been converted into conservation units, Indigenous lands, settlements, forest concessions or private properties yet.

According to a Greenpeace report, deforestation in non-destined areas around the BR-163 highway in Pará increased by 205 percent between August 2019 and July 2020, compared to the same period the previous years.

As we saw in the first article of the Forest Thieves series, which explained who was behind the largest deforestation in the Amazon, as recorded by MapBiomas, land grabbing is not for amateurs but an organized crime activity that demands large investments and the participation of multiple social actors.

On the land-grabbing “assembly line” are the people who go deep into the forest to tear it down, often working in conditions similar to slavery. And at the top of this production chain are those who finance deforestation and profit from the stolen land, either by selling it to third parties or through their own agricultural production.

Between these two extremes, however, there are intermediary agents that usually go unnoticed, but earn significant sums from land grabbing.

Impersonating a farmer interested in buying land, I chatted via WhatsApp with two realtors who work in areas close to the federal highway. When confronted by The Intercept, at the end of the investigation, one of them said that he could be killed if his name were mentioned in the report. For this reason—and given the region's history of gunfighting and murder—we will use fictitious names when referring to both.

Five minutes after receiving my first message, one of the realtors we will call Roberto was ready to look for areas of interest to me. In a few days, he sent me four options for farms. One of them, worth 135 million Brazilian real ($26 million), is located in the Castelo dos Sonhos district and covers 3,000 hectares (more than 4,000 football pitches), of which 2,200 have already been deforested and converted into pasture. Its main attraction is the relief: The area is flat, which means it can be cultivated with agricultural machinery and, consequently, be planted with soybeans. “It is a plateau, you look at an image and you have already seen everything,” the broker guaranteed.

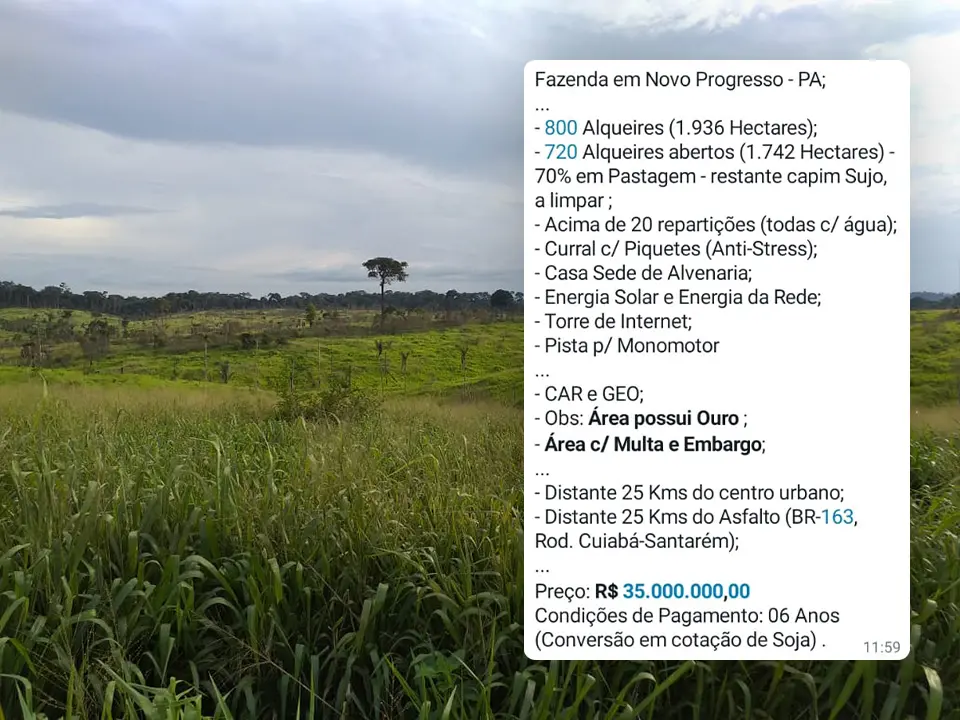

Another area on offer, this one in Novo Progresso, costs $6.8 million and has 1,936 hectares of land, almost 90 percent of them deforested—the advertisement itself points out that the area was subject to a fine and embargoed by the environmental agency, perhaps predicting that the assessments (so common in this region) are not an impediment to closing the deal. The structure includes brick headquarters, an internet tower, and even a runway for a single-engine plane. Finally, a valuable observation: “The area has gold.” The Intercept found that in the region, it is common for landowners to allow prospectors to enter their properties in exchange for a percentage of the metal extracted from illegal mining.

Under the force of gunpowder

My conversations with Roberto ended when he said that he could only send me the location of the farms if I signed a document guaranteeing the exclusivity of the deal. In it, customers undertake not to buy properties “through another intermediary or directly with the owner” or, if they do, they guarantee that they will still pay Roberto a percentage of 6 percent on the value of the property.

Meanwhile, I was also exchanging messages with Gustavo, who was soon asking the usual questions to outline a customer profile. He asked about the size of and the use for the land, the amount of investment, and the level of my demands when it comes to documentation—making it clear that if I intended to regularize areas, I would need to look further north, near Santarém.

"Wonderful. It's a big area. I’m going to look into the options here for that size,” he replied, after I explained that I was looking for a property of around 6,000 hectares for cattle raising, but that also had the ability to plant soybeans and that I would be satisfied with a CAR record from the Rural Environmental Registry and georeferences of the area: a map based on the geographical coordinates and boundaries of the farm.

During two months of conversation Gustavo offered me eight options for farms on the BR-163 axis between Castelo dos Sonhos, Novo Progresso, Trairão and Altamira, whose prices ranged from $4.8 million to $19.3 million. If the sale were to go through, the broker would pocket a commission between $145,000 and $579,000, corresponding to 3 percent of the value of the deal.

“Usually, here it's 5 percent, but if the area exceeds R$10 million, we talk about 3 percent,” he explained.

The top-of-the-line offer is a farm on the banks of the Jamanxim River, with four houses, a corral, a shed, electricity, internet and the capacity for 8,000 oxen. Located between Castelo dos Sonhos and Novo Progresso, almost half of the area—corresponding to 2,400 hectares—is already “formed,” which, in the language of land grabbing, means that the forest has been cut down and the grass is already planted. All this for about $20 million, enough to buy 12 mansions similar to those of singer Anitta in Miami.

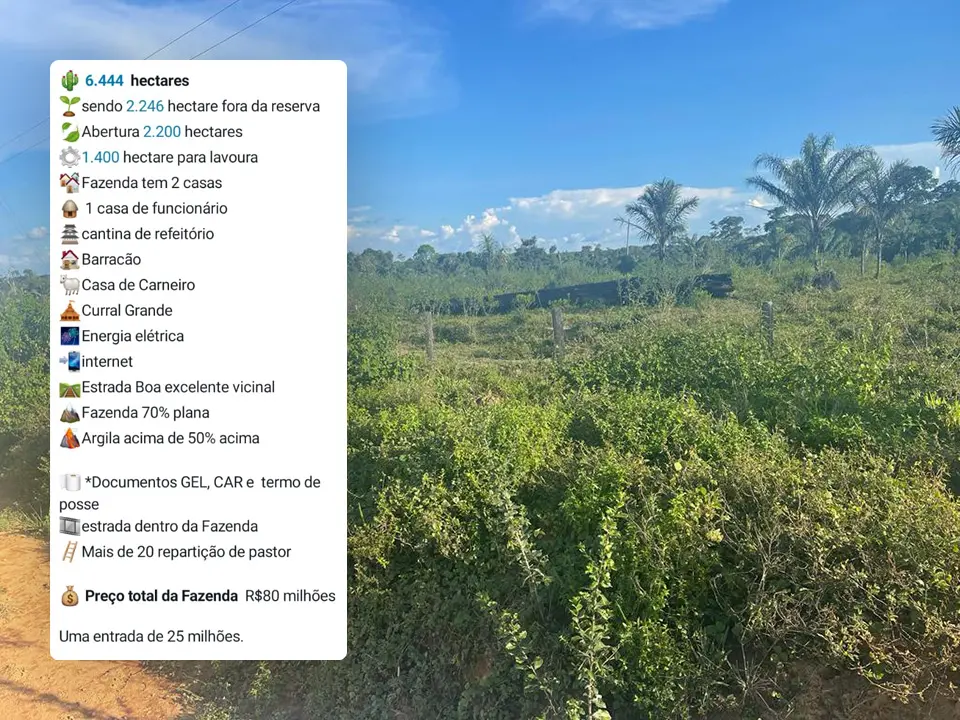

In another offer, worth $15.5 million, the seller clarifies that 2,246 of the 6,444 hectares are “outside the reserve,” an expression used in the region to refer to the Jamanxim National Forest (the second most deforested conservation unit in the country, according to environmental agency Inpe). The farm is very well equipped. It has two houses, a house for employees, a cafeteria, a shed, a sheep barn, a large corral, electricity, internet and “excellent road access.”

Our team was in one of the areas offered by Gustavo, a farm costing $6.8 million, with 4,157 hectares (of which almost 3,000 were deforested) and located in a public area not designated by the federal government—the Curuá land. To get there, we left Novo Progresso and drove 50 kilometers along the federal highway heading north, until we entered a dirt road called Diamantino. We drove for another 60 km, passing through areas where cattle are raised and other areas were still smoldering from recent fires. Finally, we arrived at the farm from the advertisement. It was covered with pasture and had a few head of cattle surrounded by vast soybean plantations. (In August, when we were in the region, the land was being prepared for planting.)

“It is a region with a lot of rich people. There, the business belongs to the people who have the gunpowder,” explained Gustavo via WhatsApp, in a reference that applies both to economic power and to the caliber of landowners to intimidate neighbors and “resolve” possible conflicts.

Those who are not as “well-armed” can buy land that still has forest standing on it, for $1,930 per hectare.

"But we can see what can improve in the price," the broker assured us. Eager to close the deal, Gustavo even sent us the contact information of a man who fells forested land in the region.

“Personnel to do felling is not hard to find here, no. We are aligning this,” he said.

In a note sent to The Intercept, the Regional Council of Real Estate Brokers in Pará, CRECI-PA, reported that intermediating the sale of land without a regular title is a “transgression” of the profession’s code of ethics, which can be punished with a verbal warning and going as far as the seizure of the professional card.

Gustavo's case is even more serious, since, unlike Roberto, he is not registered with the agency, which makes him subject to a misdemeanor criminal offense. Gustavo himself admitted that he uses a fake CRECI number.

You can read the full version of this story in Portuguese at The Intercept Brasil.