Nar Kone was 12 years old, playing in her aunt’s house in Guinea with her two cousins Kadia* and May*, when her aunt called 14-year-old Kadia into a different room to “talk.” Minutes later, Kone and May heard Kadia screaming at the top of her lungs, crying, begging for help. The two cousins immediately realized what was happening. Her cousin was undergoing female genital cutting (FGC), referred to in French as “l’excision.”

As soon as she could, Kone rushed into the house where she found a wicker mat on the floor soaked in her cousin’s blood. Now 21 years old, Kone reflects on the fact that the image still lingers in her memory.

“I saw a lot of blood,” Kone said—blood that she said was supposed to stay hidden. Her aunt quickly found her and shooed her out of the room, telling her it was forbidden for her to be there.

Kadia suffered deeply in the aftermath of her cutting, Kone recalled.

The cutting caused her to hemorrhage, and in the months afterward, her cousin was crying and unable to walk correctly, Kone said. Because the practice is outlawed in Guinea, and because the family feared Kadia would bring bad luck to the world, she was not taken to the hospital. Despite this, women were sent to teach Kadia how to be a housewife and celebrate her official transition into womanhood. They cleaned her hands to wash the bad luck away, and they sang and danced for hours.

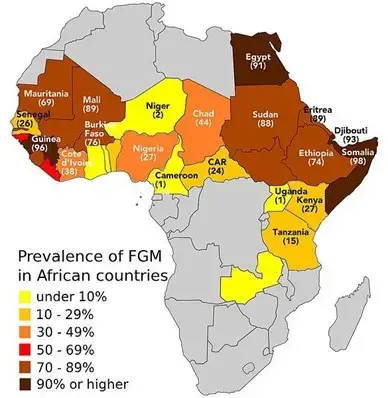

FGC is practiced around the world. It holds great importance for many cultures, including in the West African nation of Guinea, where it has been practiced for over 2,000 years. Although the practice is outlawed, 97% of women age 15 to 49 have undergone some form of FGC, according to the United Nations Population Fund. Government officials and religious groups work to combat the practice, yet discussions with female victims in Guinea show that these efforts are failing.

Kadia was by no means alone in her suffering. FGC can have fatal health complications, including hemorrhaging, death during childbirth, and the transmission of HIV. In many cases, FGC removes a woman’s ability to experience any kind of sexual pleasure, making sexual intercourse painful for the remainder of her life.

The practice is also rarely consensual. “All girls are afraid” of the cutting, Kone said, because they know that they could become very sick or die, and so they will often try to escape. They are held down, tied up, and often blindfolded during the cutting.

Both the World Health Organization and United Nations have condemned the practice as a violation of the human rights and health of women and girls.

A primary reason for the prevalence of the practice is that it is commonly believed by both Muslims and Christians alike that cutting decreases sexual desire, thus increasing the chances of a daughter remaining a virgin until marriage. Women believe that if they do not cut their daughters, “their daughters will want sex all the time,” said Emmanual Koroman, Guinean Director of Christian Affairs.

“Islam’s deep respect for women is why FGC occurs,” said Elhaj Bangaly Sangali, an imam in Conakry. He was wearing an all-black thobe, a long straight-cut garment traditionally worn by Islamic men, with silver detailing, which matched his taqiyah, a Muslim cap. “Islam respects women. [It] must conserve women and protect their modesty. This includes protecting women’s genitals. If women have no husband and are not cut, they cannot control themselves.”

“Women,” he concluded, “are the source of humanity.”

Imam Sangali studied Islam for most of his life, attending university in Malaysia and Thailand. He acknowledged that Islam never specifically decrees cutting girls but believes that because the religion never forbade it, it is permissible.

Although Imam Sangali may be one of the most outspoken supporters of FGC, the general population echoes his beliefs: A Guinean study found that 68% of women and 57% of men believe that FGC is a religious obligation. Former Guinean Minister of Education, Dr. Bano Barry, states that religious beliefs are one of the primary reasons cited for performing FGC on one’s child. (Other reasons mentioned included promoting abstinence, cultural respect, and the shame of being uncut.)

Aboubacar Nabe, a Muslim religious leader and member of Guinea’s Secretariat for Religious Affairs, has heard time and time again that Guineans assume FGC is tied to their religion. Although neither the Quran nor the Bible (89% of Guinea is Muslim and 7% are Christian) mention FGC, it is a common myth, Nabe said, that FGC is required by both Islam and Christianity.

Organizations in Guinea, including religious authorities, nonprofits, and governmental officials, are trying to combat FGC with religious arguments based on the Quran and Bible. Since the two issues are deeply intertwined for Guineans, the strategy, spearheaded by the government, is meant to combat the root of the problem. It uses religious figures to dispel the myth that FGC is integral culturally and religiously.

Religious anti-FGC work is led largely by men and disregards the importance of women in leading the fight against FGC. However, other anti-FGC activists say that FGC is an act perpetuated both by and against women, and thus any effort to combat it must include women.

Djomandé Djessira, the Vice President of the National Network of Traditional Communicators (RENACOT), similarly acknowledged that need. On the one hand, she said that religion is extremely important and influential, and any effort to convince people to abandon FGC must address religion. But, to really make a change, Djessira said, members of the target population must be the ones to spark change. Say, she said, that you come to a place where “women are topless with no shoes.” “Coming as modern [clothed] people, you cannot influence them,” she stated. Dr. Barry, in his study mentioned above, found similar results in his research, writing “the message must be from the target population.”

In another interview, Siba Alexis Dopavogui, who works to combat FGC in Caritas Guinée, the Guinean offshoot of the Catholic charity organization, acknowledged that he does not know how women feel, and emphasized the need for women to be the actors of change in the movement. Without the message coming from the target population (in this case, women), he said that the rates of FGC will not decrease.

Several women I interviewed agreed that the issue of FGC is multifaceted, relating not only to health but also to problems of sexual pleasure, consent, and women’s rights. Because the effort has been led by men, the movement has become disconnected from the problem it is trying to solve.

For example, Nar Kone’s issue with FGC lies in the lack of consent and information about her own body that she was denied. It was in a medical biology class that she says she realized her vagina looked different than her classmates'. She knew she had been cut like most of the other female students, but her vagina looked distinctly unlike theirs. She went home, inspected herself in the mirror, and realized that her vagina had also been sewn shut after the cutting.

Kone said that she was a victim of FGC at age four and has no memory of the incident. No one in her family had ever told her that her labia were sewn together. This discovery explained her constant infections and painful periods. However, Kone cared less about the medical complications this had caused her and more about the fact that she had not consented to being cut and that no one in her family had ever told her this life-altering information about her own body. It costs around $500-$600 to get corrective surgery, a surgery Kone cannot afford without the help of her parents.

“My parents will never give me the money [to afford the surgery],” Kone said. Her mother told her to keep herself sewn shut until marriage. Kone disagrees. “When I have the money, I will.”

Aissatou Diallo, 28, was 11 years old when she was kidnapped in broad daylight by her mother’s friend and taken to the forest to be cut. She says she bled so much that her family was forced to take her to the nearest hospital. After she was married, she discovered that she was physically incapable of having sex. She and her husband went to the gynecologist, where they were told that she would have to undergo surgery. The surgery was grueling, and it took days for her to recover. Today, sex is still so painful that she sobs every time.

“I have never felt pleasure with my husband,” Diallo said. “I would do anything to be able to feel pleasure while having sex with my husband. I have lost something great.”

In an interview, Camara Souleymane, Chief of the Guinean Project of FGM/E [refers to female genital cutting and excision], described the many efforts that the government was undertaking to end FGC, in conjunction with religious authorities and groups such as the National Network of Traditional Communicators (RENACOT), who represent traditional sources of authority in the community. He focused solely on health repercussions (often maternal), without mentioning sexual pleasure or consent, often interrupting those he was speaking to and snapping his fingers at them. These people more often than not happened to be women.

Souleymane said that he also works with UNICEF, UNFPA, and Plan International as well, along with the governmental Ministers of Health, Justice, Religious Affairs, and Education. He introduces anti-FGC material into Friday programming and referenced a phone number that a woman could call to report an illegal cutting—a number which, upon further questioning, turned out to be non-functioning due to technical difficulties.

The only reason to address FGC is because of its “repercussions in the health of women. That’s why we work against it,” said Koroman, the Guinean Director of Christian Affairs. He spoke for an hour about the training the government does for church authorities, all of which focuses on the potential health problems, but not on women’s rights or consent.

Even religious groups acting without the traditional obstacles of government bureaucracy fail to address these issues of consent, women’s rights, and sexual pleasure. For example, RENACOT wields great influence on the community in many different ways—some religious, some cultural. They meet regularly to discuss ways to aid Guinea. At their June 1, 2022, meeting, the leaders consisted of five men, two of whom were imams, and one woman, aforementioned Vice President Djomandé Djessira. The group discussed their plans to fight FGC by talking about its various health issues. They centered around death during childbirth, once again ignoring issues of women’s rights and sexual pleasure in favor of health alone.

Views like the ones held by Diallo and Kone, which are incredibly common and reflect the genuine thoughts and emotions of the affected women, are rarely addressed by current Guinean religious programming. Sexual pleasure for women is often a taboo topic, treated as something that will increase promiscuity. In every story, women discussed how they screamed, cried, and tried to run away—but programming focuses on infections rather than the immorality of a forced cutting of a young girl’s body. Money is thrown at these religious authorities by government and international NGOs alike.

However, the religious groups, as well as the government and the NGOs that work with them, are majority men—out of interviews with eight NGOs fighting FGC, only one had a woman in a position of power, and both government officials working on the issue were men.

The one woman in power was 21-year-old Kadiatou Konate, founder of Club Jeunes Filles Leaders de Guinée, or Young Female Leaders of Guinea Club. She founded the club a few years ago with two of her friends, and since then, the club has grown to over 500 members. Her mission aims to give girls a voice, and she has a variety of programs addressing different women’s rights issues, from child marriage, to sexual violence, to FGC. Konate said she also works with religious groups from Christian, Muslim, and Indigenous religions.

Konate, in contrast to representatives of the other NGOs, governmental groups, and religious groups I interviewed, has ensured that her organization is overwhelmingly comprised of women. At the headquarters, not a man was in sight, and a quick glance at the Facebook page for the organization shows almost exclusively women. The club also addresses women’s rights broadly, not drawing a line in the sand at FGC but recognizing that child marriage, FGC, rape, and more are part of a broader issue of Guinean women’s rights. Konate also, like Djessira, stressed that the club must “adapt their message” to their target audience.

When Kone discovered she had been sewn shut without her consent, she said that she became a feminist and anti-FGC activist. She has made public Facebook posts sharing her experience, and has traveled to markets and schools to speak to local women about the dangers and problems of FGC.

Diallo also saw her lack of rights and independence as the reason for her lifelong suffering, and she decided to devote her life to helping other women. She created the Training and Literacy Learning Center to teach young girls reading, writing, and technical skills (such as sewing) so that they can become self-sufficient. In the course of her teachings, she has from time to time talked about FGC. She makes sure to always mention to her students that FGC is not in the Bible nor in the Quran, as she recalls that when she was a child, she thought FGC was a religious rite.

It is Kone and Diallo’s stories that will empower others to stop FGC so that their daughters will be spared.

Editor's note: *Kadia and May's names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Interview translation from French to English was provided by Fatima-Ezzahra Bendami.