I left Africa last night with a great deal of gratitude for the people who have shared their stories with me, especially the farmers. Never have I encountered such a wide variety of experiences, skills and backgrounds, but all of them were willing, even eager, to share their thoughts with an American journalist. They include:

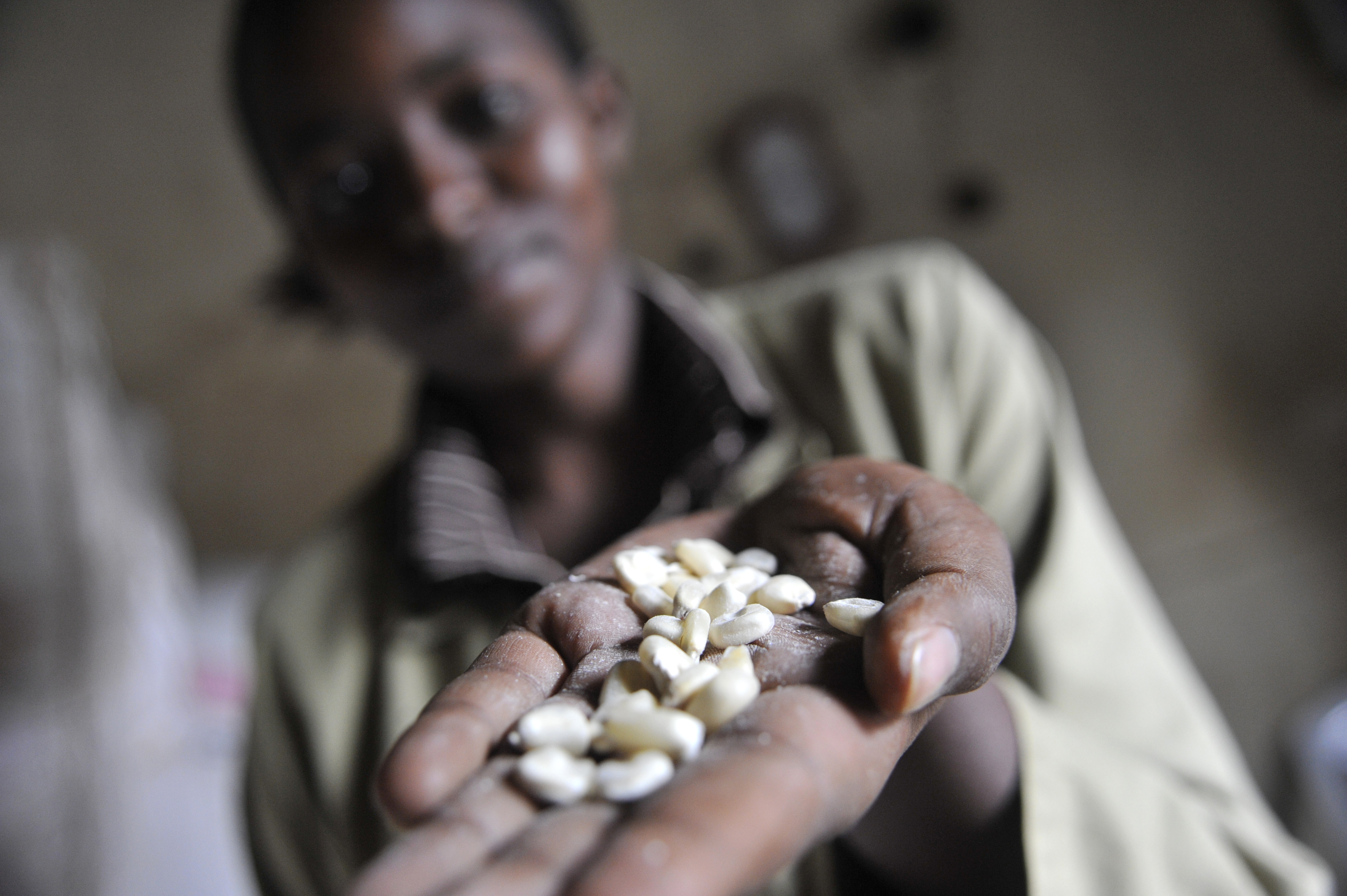

Janet Kaindu, who had lost her second crop in a row of maize and beans on her plot in Kenya's Rift

Valley, which remains wracked by a drought that won't break. She planted her latest crop in October, counting on El Nino rains in November that never came.

Joshua Maweu, who patiently showed my photographer and me around his farm near Machakos, Kenya, even as he clutched 90 pepper seedlings that he was eager to plant now that it had finally rained overnight.

Joseph Mokirah, a Maasai farmer in the Rift Valley who at 22 may be just one of the most daring and innovative farmers I've ever met. He's certainly one of the youngest. He's turned a a few acres of what is essentially desert into a vibrant corn and vegetable farm that is feeding his family and making a profit. The secret was persuading his family to sell enough cattle to have a well dug. Experts say this Pkind of success could be repeated elsewhere, if the government were willing to put the money into irrigation. One of my big regrets of the trip is that I wasn't able to persuade Joseph to record his success for Americans to see. The Maasai are often reluctant to be photographed.

Alastair and Peej Wood, brothers who operate a second-generation farm in Kenya where they produce corn seed for Monsanto and corn for food. They're eager to use genetically modified seeds but skeptical any technology can really make corn more resilient in drought.

Tommie Olckers, who showed me around farm holdings he manages in South Africa that are big even by American standards. They include 9,500 hectares, or more than 23,000 acres, of corn and canning beans, in an area east of Pretoria where the flat country is occasionally studded with the hills of yellowish sand that are the remains of abandoned gold mines. He does it, as every farmer here must, without a dime of government subsidies. That lack of government support has hastened the end of many farms, leading to consolidation into bigger operations.

Isaac Khuto, who has gone from driving a taxi to fulfilling a dream of running a farm, something only whites such as Olckers did not that long ago in South Africa. Now, he's conducting his own field trials of biotech and conventional seeds to make sure he knows which one type is best for him.

I came to Africa quite frankly with a great deal of skepticism about the potential for genetically modified crops to make a difference in food production in this part of the world. But the story has turned out more complicated than I expected. Yes, farmers, especially smallholders, have challenges that go well beyond the yield potential of the seed they buy. But food shortages are a real prospect as drought seems to go on and on in parts of Kenya.

And Kenya especially bears watching in the next few years as the government implements new biosafety regulations and Monsanto pushes forward with plans to introduce insect-resistant corn seeds. The technology has taken off in South Africa, at least with corn, where two-thirds of what is planted now is now biotech. More would be except for export markets that insist on non-GMO maize. Olckers grows a relatively small amount of GM corn for now, but not because he doesn't like it. Would farmers in Kenya, and elsewhere in Africa, embrace GMOs as readily? Will they get the chance? Should they?