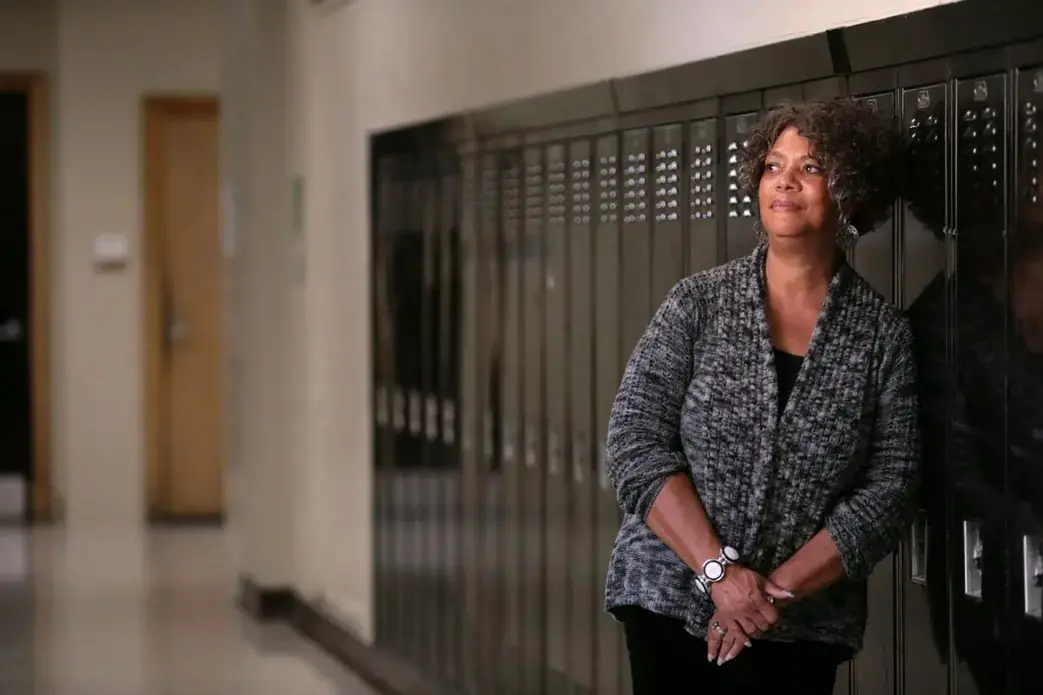

UNIVERSITY CITY — When an acquaintance contacted Judy Gladney to see whether she would be attending their 50th high school reunion next weekend, she blew him off. Why bother, she thought. The only other University City High School reunion she went to — she can’t remember if it was the 20th or 25th — wasn’t an experience she wanted to revisit. She barely knew anyone there, and almost no other African American alumni attended.

You won’t find her name in the history books, but Gladney, now 67, had been in the first phalanx of African Americans to integrate U. City schools in the mid-1960s. In her class of ’69, there were approximately 60 black students among more than 600 whites, most of them Jewish.

“I always felt like an outsider at U. City,” she said. “I didn’t fit in with the white kids, I didn’t quite fit in with most of the black kids. You’ve got all this teenage angst, you’re trying to find your niche, and where was my niche?”

Even so, the idea of attending her 50th would grow on Gladney. The prospect of the reunion had caused her to reflect on the role she and her late ex-husband Eric Vickers, University City Class of ’70, had played in the life of a unique community. University City is nationally known for its diversity and progressive approach to everything from the arts to housing to education.

At the same time, the U. City school district’s struggles are well-known. Considered among the best in the state in the mid-20th century, by the turn of this century student achievement had fallen precipitously as the district transitioned from a middle-class student base to one with many more disadvantaged students. More recently, under new leadership, student outcomes have improved.

Like other communities here and nationwide, University City saw some whites respond to desegregation by leaving. A University of Missouri-St. Louis study reported that 28 percent of white residents fled U. City during the 1960s. But then due to an exceptional amount of cooperation and collaboration among local officials and citizens that drew national recognition, the population stabilized.

Even so, white parents who continue to live and buy homes in University City have participated in a form of white flight by sending their children to private and parochial schools. In a city with a population that is 54 percent white, the public schools are 80 percent African American.

For better or worse, Judy and Eric leaned into U. City as adults and parents, buying a home close to where Judy grew up and sending their children, Erica and Aaron, to the public schools. The couple later divorced, and Eric died of pancreatic cancer in 2018. Judy now lives in St. Louis, but Eric’s dad, Robert Vickers, 92, a former Venice, Ill., school superintendent, continues to live on Dalkeith Lane in U. City, as he has since 1967. His great-grandchildren, Eric and Judy’s grandnephews, attend U. City schools.

The Nearest Thing to a Good Place

Judy’s parents, Dr. John and Clarice Gladney, moved to U. City from the city of St. Louis the summer before Judy, the youngest of their three children, started ninth grade. It was 1965, and the Gladneys were the first black family to buy a home in University Hills, a gated neighborhood south of Delmar Boulevard. John died in 2011 and Clarice in 2012, but their memories were recorded for an oral history project, available at the University City Library.

As John Gladney put it, the family chose U. City because “it was the nearest thing to a good place to live.” He’d been active with civil rights groups that pushed to desegregate schools, banks and other businesses in St. Louis. He also was a pioneer in other respects. He became the head of the ear, nose and throat department at the St. Louis University School of Medicine, the first African American to lead a department of otolaryngology in the U.S.

He and Clarice wanted to live the dream, though clearly it was not going to be easy to see it fully realized.

“We were told the city fathers had decided black people could only live north of Olive,” Clarice recalled in the oral history. “We didn’t want to be put back into a ghetto situation.”

The Gladneys could not find a real estate agent who would show them houses south of Delmar Boulevard. So when a doctor friend told John about a house for sale at 7361 Teasdale Avenue, in the Hills, he knocked on the homeowner’s door one Sunday to inquire. The homeowner liked the Gladneys but later learned her agent wouldn’t handle the sale. So the woman waited 120 days until her contract expired with the agent, then closed the deal.

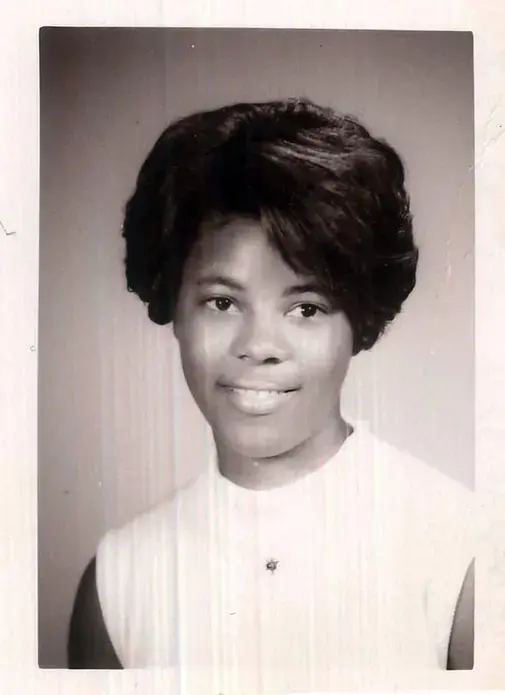

Judy would have been just fine if it hadn’t happened. As a then 13-year-old, she had not bought into the life her parents imagined for her. She wanted to follow in the footsteps of her brother and sister, who both graduated with honors from Beaumont High School in north St. Louis.

“I felt robbed,” Judy said.

As a ninth-grader at Hanley Junior High, Judy was one of a handful of African American students and pretty much one of the only ones from U. City’s more upscale south side of town. Judy remembered being placed in a math class at Hanley that was not very challenging. “One day the teacher called me to the front of the class and said, ‘I don’t understand why you’re in this class.’ What he was saying is, as a black person, I had been put in a math class below where I should have been. Apparently, there was tracking and I had been tracked down.

“And so that was my first takeaway of racism in the U. City schools. Thank God the teacher was open-minded enough, and I got placed in an accelerated (math) class at that point.”

Living in beautiful University Hills was a double-edged sword for Judy. She grew tired of feeling “different.”

“We were always the ‘negroes’ that white folks felt comfortable with,” Judy said. “It used to tick me off that I was never introduced by my name to many people. I was always ‘Dr. Gladney’s daughter.’”

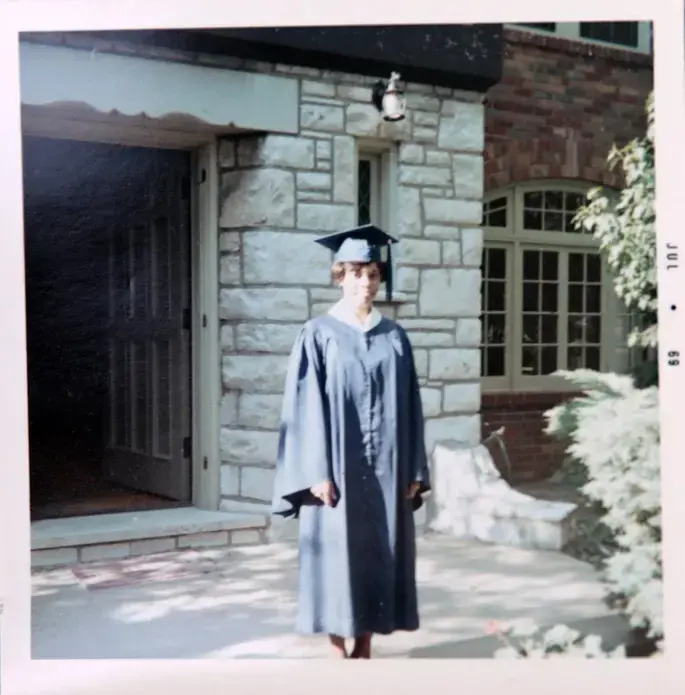

Judy grew to accept life as a student in a more culturally diverse community. She played on the high school’s tennis team, was a member of the student council and maintained a rigorous load of classes. Still, she says she “wasn’t hanging with a whole lot of folks” and never formed close friendships with the white students. They had already formed their circles of friends in grade school, she said. Most were friendly, but she was never invited to any of their homes or to their parties.

Judy’s strongest white allies were her teachers: Dennis Lubeck, a social studies teacher, and Karen Berger, an English teacher. They tapped her, and two other students, to participate in a summer enrichment reading program held at Berger’s home.

She proudly remembers the other students: Clement Cann, who would go on to Harvard and a distinguished career as a filmmaker and videographer, and Diane Ridley (now Ridley Gatewood), who earned a law degree from Northwestern and recently retired as an assistant New York attorney general with a long list of honors.

Judy also remembers Joyce Ladner, who mentored her on an independent study project. Ladner, a civil rights activist who was then working on her doctorate in sociology at Washington University, later played a key role in restructuring the public school system in Washington, D.C.

“How many high school kids are mentored one-on-one by someone who would go on to serve in the Clinton administration?” Judy marveled.

Missing U. City

After graduation Judy moved to Washington, D.C., to attend Howard University, studying there for two years before transferring to Washington U. where she and her future husband, a political science major, began dating.

Judy Gladney and Eric Vickers were married in 1975. After he graduated from law school at the University of Virginia in 1981, the couple moved back to St. Louis and he became a renowned and controversial civil rights activist. She was nine months pregnant with their daughter, Erica. They had another child, Aaron, six years later.

The couple lived in the Pattonville school district portion of Creve Coeur until 1987 when they moved to a home in U. City so that Erica could start first grade at Jackson Park Elementary School, a more racially diverse school than what Pattonville then offered.

“The elementary school was excellent,” Judy said. “They had an African American principal named Gloria Davis who offered strong leadership, which resulted in good test scores for the students.”

Judy was especially impressed by the school’s math program, which used timed tests to build students’ skills. “Erica pretty much became a math whiz, which I think influenced her to go into accounting.”

But by the time Erica got to middle school, Judy had become disenchanted.

“When she was in seventh or eighth grade, she brought home a paper with an A on it and I noticed all of these grammatical errors,” Judy said. “I made an appointment with the teacher, a black male teacher, and I said you know, you probably never had this happen, but I’m not happy that you gave her an A because this is unacceptable. If I’m pointing out all these grammatical errors, how is she going to be prepared for college?

“He said, ‘Well I don’t teach reading, I teach social studies and she answered all the questions right.’”

Judy said by the time Erica got to high school, the atmosphere was even more lax.

“What I noticed is it was a school within a school because there were kids who were still going to all the Ivy League schools, black or white, if they applied themselves. And then my daughter and son liked to be with the ’cool’ kids, so they weren’t applying themselves.”

Judy said the district continued to decline and that had a much greater impact on Aaron, six years younger than Erica.

Aaron, now 32, agrees.

“Teachers were pushing along kids, even if you didn’t understand the subject,” he said.

So concerned was Judy that a couple of years after she and Eric divorced, she took an apartment in Creve Coeur so she could send Aaron to Pattonville High School. Aaron would later move in with his dad and finish high school at Soldan in the city.

Aaron says despite going to high school at Pattonville and Soldan, he always kept in touch with his friends from U. City, even to this day.

Erica Vickers Cage is now 38 years old and lives in Shiloh, close to where her husband, Warren Cage, works. She has a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Lincoln University in Jefferson City.

Erica says she misses U. City. It pains her that her three children haven’t grown up with more African Americans.

“I’ve always grown up around diversity. It’s something that I embrace and something that a lot of people don’t understand. It’s all you know and all you want.”

The family maintains ties to U. City Schools. Eric’s niece, Kwira Vickers Wright, who is the dean of students at KIPP Inspire Academy, a charter school program in the city, chooses to continue the Vickers tradition of living in U. City and sending her children to its schools. Her son, Rashad, 16, is a sophomore at the high school, and Jahleel, 11, attends Jackson Park.

“I am U. City to the heart,” Kwira says.

The family appreciates that the district has focused an uncommon amount on equity, restorative justice practices and community service projects, the kind of work that was so important to Eric and Judy and their parents.

An Invitation

The memories and the emotional connections her family maintains made Judy rethink the U. City Class of ’69 reunion.

She now plans on attending. But before that, she will share her story at a separate public event at 6 p.m. Friday at the U. City Library. Maybe some of her classmates will attend.

If so, unlike the last reunion when the time passed so slowly, and almost no one spoke with her, Judy expects she will have much more to talk about with her classmates concerning U. City’s yesterdays, and now she looks forward to its tomorrows.

Sylvester Brown Jr. and Sally J. Altman also contributed reporting and information to this story.