On a calm, bright morning in August 2007 a pair of Russian submersibles dropped 14,000 feet to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean and planted a flag made of titanium at the North Pole. It was a bold move, made with drama in mind, and images broadcast around the world of the Russian tricolor standing on the seabed drew quick condemnation in the West.

“This isn’t the 15th century,” said Peter MacKay, then foreign minister of Canada, on CTV television. “You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say, ‘We’re claiming this territory.’”

MacKay was technically correct; the Russian stunt held no legal weight. But his rebuke carried a note of petulance, as though he wished the whole thing had been Canada’s idea. Ten years on, MacKay’s reaction is easier to understand. 2007 was, at the time, one of the warmest years on record, and the Arctic summer ice pack—the vast expanse of floating ice that covers the North Pole even through the summer—had shrunk to the lowest levels ever recorded. The frozen polar sea, foil to human ambition for centuries, appeared to be melting, and Russia was staking a symbolic claim on whatever lay beneath the slush.

“The summer of 2007 saw the largest Arctic ice-loss in human history and was not predicted by even the most aggressive climate models,” says Jonathan Markowitz, assistant professor of international relations at the University of Southern California. “This shock led everyone to suddenly understand that the ice was rapidly disappearing and some nations decided to start making moves.”

In the decade since that “shock event,” the Arctic has been transformed by rising temperatures, vanishing ice, and international attention. Countries with Arctic territory—and some nations with no polar borders—have been scrambling for advantage on the Earth’s latest frontier. Entrepreneurs, prospectors, and politicians have all turned north, recognizing that less ice means more access to the region’s rich stores of fish, gas, oil, and other mineral resources.

“Predictions about the Arctic Ocean have been wrong,” says Michael Sfraga, director of the Polar Initiative at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. “And now there’s an ocean opening up before us, in real time. This hasn’t happened before.”

But Arctic investment has been uneven, and some nations are vastly outperforming others. Russia and Norway have been the most proactive Arctic nations, according to Markowitz, spending heavily on natural gas and oil infrastructure. Russia’s ice-capable fleet is the largest in the world, numbering some 61 icebreakers and ice-hardened ships with another 10 under construction. Norway's ice-hardened fleet has grown from 5 to 11 ships. South Korean shipyards are busy building ice-hardened cargo vessels, and China has invested billions in Russia’s liquid natural gas network.

The Chinese are more than passive investors, however, and their Arctic maneuvers tend to generate some of the loudest headlines. In 2016, a Chinese mining company tried to buy an abandoned naval base in Greenland. In 2017, the first Chinese icebreaker sailed through the Northwest Passage on a scientific survey. And in 2018, the Chinese government published a white paper outlining its Arctic plans—and its intention to play a greater role in the region.

Other Arctic nations, including the United States, Canada, and Denmark, lavish far less attention on their northern territories. Sfraga and others have called the U.S. a “reluctant Arctic power,” and Markowitz points out that although Canada often talks about raising its northern game, there’s little behind the words.

“National interests are largely a function of income and revenue,” Markowitz says. “What states make influence what they take, and states that make things—like the U.S.—are much less interested in securing Arctic resources. The Russians, on the other hand, don’t make much. They don’t have a Silicon Valley or a New York City and they view the Arctic as their strategic future resource base.”

The disequilibrium in Arctic approaches has worried some observers and led to news headlines that regularly describe the Arctic as a kind of Wild West, or as a frigid theater where nations will square off in the next Cold War. Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 and China’s ongoing play for military dominance in the South China Sea have intensified anxiety.

Markowitz, who has been tracking military development in the Arctic for years, says that Russia maintains 27 operational military bases above the Arctic Circle, more than double the number it had before the “shock event” of 2007. The U.S., in contrast, keeps just one base in the Arctic, an air force installation on borrowed ground in Greenland. Canada, which is second only to Russia in the size of its northern territory, has only three small Arctic bases.

Canadian and American forces do operate bases just south of the Arctic Circle, though, in Alaska and the Northwest Territories, and Sfraga said both nations are capable of rapidly dispatching aircraft, troops, and submarines into Arctic territory. The two nations are also slowly expanding their cold-weather military infrastructure. Canada is building a naval refueling base on Baffin Island, and the U.S. announced plans earlier this year to re-establish the Navy’s Second Fleet, which will counter Russian activity in the North Atlantic.

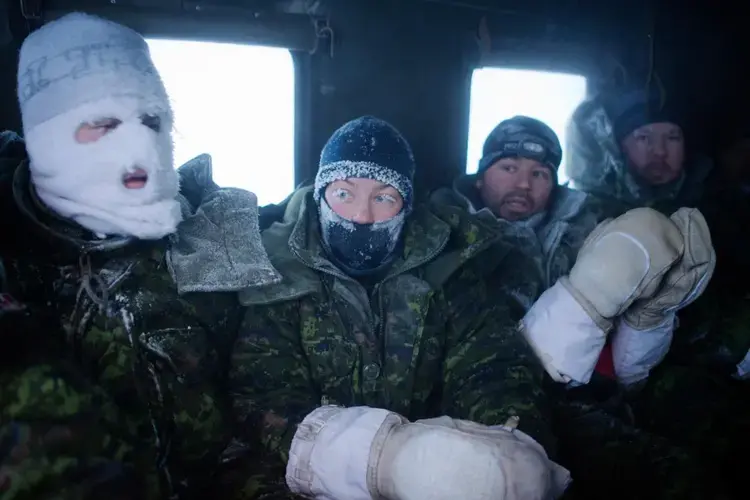

In the meantime, Canadian and U.S. forces, along with other members of NATO, continue to regularly train for cold weather conflict. Today, in Norway, NATO opens its largest training exercise since the end of the Cold War—two-weeks of war games involving 50,000 troops from 31 nations. The massive operation, called Trident Juncture, imagines a scenario in which northern Norway is invaded, prompting allies to rush to its defense. The gallery here reveals how extreme even practicing for a war in the north can be.

While the imaginary enemy in Trident Juncture isn’t named, Norway shares Arctic land and sea borders with Russia, and tension between the two nations has risen in recent years. Some observers worry that future disputes between the neighbors over fishing or mineral rights could pull the NATO alliance into a conflict for which it is unprepared.

Still, the Arctic remains one of the world’s calmer regions, where contact between nations is relatively open and stable. Russia, Norway, the U.S., and five other Arctic countries are all members of the Arctic Council, a group formed in 1996 to encourage communication and cooperation across the pole. Even as NATO forces gather in Norway, the council continues coordinating meetings on Arctic science, environmental issues, and search-and-rescue operations.

Sfraga and Markowitz agree that the Arctic Council, operating outside the military framework of NATO, offers one of the best paths forward for easing strain. Some experts also point to the south pole—where an international treaty has preserved Antarctica “for peaceful purposes only”—as a model for what could be possible in the Arctic.

For now, many military and political analysts consider the Arctic an unlikely battlefield. Global warming has begun transforming the region, but the qualities that have frustrated human ambition and desire in the north for hundreds of years remain powerful.

“If it came to war in the Arctic, you’d really be fighting two enemies,” Brigadier General Mike Nixon said last year at the headquarters of Canada’s Joint Task Force North, in Yellowknife. “And the more dangerous of them would be the cold.”

Nixon was careful to say that Russia’s Arctic military activity remains well below Cold War levels, and he dismissed the idea of potential land grabs or invasions. The cold is too intense, he said, the ice pack still vast and thick, the polar distances enormous. Planting a flag at the bottom of the sea is one thing. Sending troops across the ice is quite another.

“If someone actually decided to launch an attack over the pole,” Nixon said, “it would quickly turn into the largest search and rescue operation the world has ever seen.”