Alaska’s biggest salmon run is booming despite warming water, and scientists are trying to understand why.

PICK CREEK, Alaska—In mid-July, sockeye poured into this stream, skittering through the shallows balanced on their bellies as their backs thrust out of the water.

They were easy prey for a brown bear that dashed into the creek to feast on only the choicest morsels. The bear grabbed a female, sucked out the eggs and flung her body—still squirming—to the ground. From a snaggletoothed male, the bear took a quick bite of the back—turned a deep pink color—before discarding him on a sand bar in search of more flavorful fare.

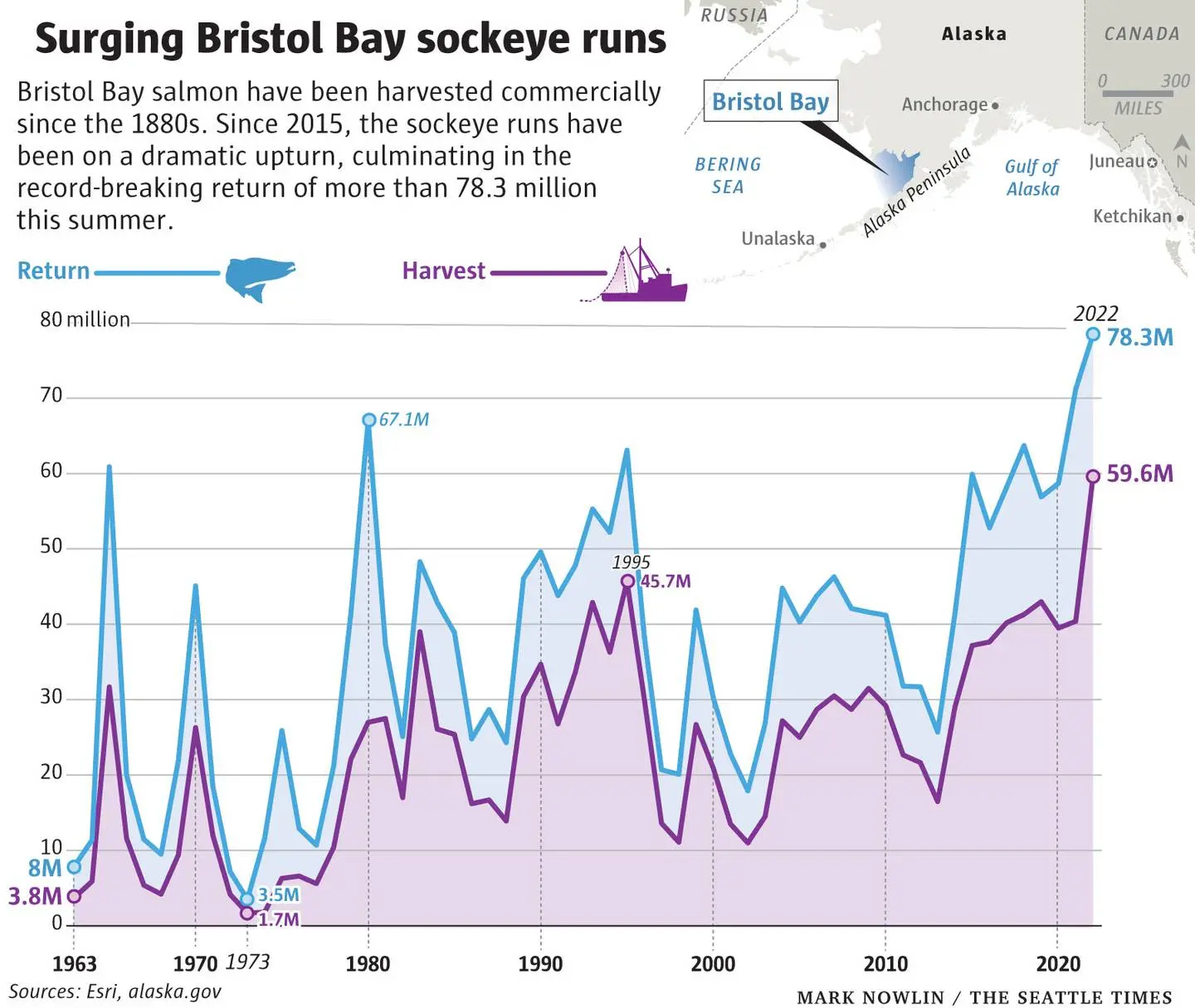

These fish were part of a record surge of more than 78.3 million salmon that returned this summer to Bristol Bay, providing a mainstay harvest for thousands of fishermen from Alaska, Washington and other states. This spectacular display of abundance in the northern realm of sockeye came during a warming century when some wild salmon runs often have struggled.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The Bristol Bay sockeye spend much of their lives in the Bering Sea, and studies have found that they generally do better in years when water temperatures climb a few degrees Fahrenheit. During the past decade, which has included marine heat waves in 2018 and 2019, sockeye, though smaller in size, stormed Bristol Bay in a series of big runs. This year’s return smashed the previous high set only last year.

Meanwhile in western Alaska, the Yukon River’s runs of king and, more recently, chum—both mainstays of Native fishermen—have imploded, shutting down harvests for the past two years.

Scientists are trying to better understand what conditions improved to produce a steroid-like boost in recent wild sockeye runs.

They are also grappling with another question in a century of intensifying climate change stoked by human activities that release greenhouse gases: Will it eventually get too warm, and undermine the extraordinary productivity of Bristol Bay sockeye?

Already there is one unsettling trend: Adult Bristol Bay sockeye in recent years have been steadily smaller as they return to spawn.

“There’s a tipping point somewhere,” said Daniel Schindler, a University of Washington fishery scientist who spends summers studying these fish. “How far are we from that? Will it be 10 years or 100? We don’t know.”

The pace of this warming could have huge consequences for the world’s largest harvest of wild sockeye, which has emerged as a global model of a sustainable salmon fishery.

Most sockeye are netted during a brief few weeks in late June and July as they return home from years living in the ocean to try to spawn in five freshwater drainages spread across southwest Alaska.

This commercial harvest of Bristol Bay sockeye began back in the 1880s when schooners started to catch and salt the salmon. The development of canneries—and later freezing lines—by largely Washington-based processors helped stitch together the economic ties that still bind Alaska’s seafood industry to the Pacific Northwest.

This year, the sheer scale of the harvest—unfolding amid the COVID-19 pandemic and global supply chain disruptions—intensified the seasonal challenges of the annual mobilization.

The preseason forecast cited the potential of a harvest of up to 60 million salmon, and shippers struggled to stockpile enough freezer containers to bring the fish to global markets.

To catch these fish, a fleet of some 1,500 gillnet boats converged in Bristol Bay, and more than 900 beach-based crews stretched setnets into tidal waters.

Processors flew in thousands of workers and contracted with an armada of vessels, ranging from World War II-era scows to Bering Sea crab boats, to ferry the fish back to the plants.

“Things get really tense, and we’re juggling, juggling, juggling,” said Blake Benson, fleet operations manager for Seattle-based Trident Seafoods.

On July 11, in the late-evening twilight of Alaska’s summer, Michael Fourtner, of Adna, Washington, spotted a jumping sockeye from the bow of his boat, a promising sign that more were close by. Fourtner and his four crew members unfurled 1,200 feet of net from the stern deck in the choppy waters off the mouth of the Naknek River.

Since mid-June, fishing through days and most of the nights, they had already caught some 200,000 pounds of fish—more sockeye than Fourtner had ever brought in during his 12 years fishing the bay.

The best single haul of his career was on the previous night, when gusty winds prompted some fishermen to set anchor. Fourtner encountered what he described as a “wall of fish” as some 2,000 sockeye hit his net.

This evening, Fourtner was eager for more. He was elated to see eruptions of whitewater along the net as sockeye got caught in the mesh.

“Holy smokes,” he said. “What a year. This is just phenomenal.”

Fourtner grew up in Homer, Alaska, where he started fishing for salmon at age 9. He settled in Washington in 2004 and returned to Alaska each year for his work as a Bering Sea crabber on the Time Bandit, a boat long featured on Discovery Channel’s “Deadliest Catch.” In 2013, after 15 years on the boat, he got a call from his wife that she was pregnant with twin girls, and he quit to spend more time at home in southwest Washington.

Fourtner now works as a sales rep for a marine engine manufacturer while fishing summers in Bristol Bay. Last winter he also found time to overhaul his 1991 aluminum fishing boat in his garage. He rechristened it Twin Tuition in hopes it would help pay the college bills for his daughters, now 9 and already eager for their first stint fishing.

In the predawn hours of July 12, Fourtner and his crew finally took a few hours to sleep, four of them collapsing into cabin bunks in a cacophony of snores and a fifth on a mat in the galley.

“I got to keep rolling because the fish are only here for a short amount of time. But you got to be safe,” Fourtner said.

The volatile mix of big loads of fish and bouts of rough weather can have grave consequences. This summer, at least four boats were lost—although none, as in some years past, resulted in loss of life.

Randy Shipman, of Sedro-Woolley, lost his boat, the Summer Solstice, early in the harvest.

His boat was drifting toward a boundary line, beyond which it would be in an illegal zone and subject to a fine. To speed things up, the crew pulled in the net without first picking out many salmon. This created a big, heavy pile in the stern. The waves got bigger, and then the boat suddenly rolled over.

One of Shipman’s buddies had been monitoring the whole fiasco and positioned his vessel nearby for the rescue.

Shipman’s season was over. Even if he could find another boat, his crew was unwilling to head back to the bay.

A video screen hanging in a small office at the Trident Seafoods plant in Naknek displays a giant map of Bristol Bay with the locations of dozens of vessels contracted by Trident to gather the salmon caught from fishing boats.

Through most of June and all of July, this is where fleet operations manager Benson tried to puzzle together how to keep fish flowing into the Trident shore operation as well as a floating processor—or when the volume became too great, into more distant plants on the Alaska Peninsula. This task was complicated by big tides, which at a low ebb could make river channels impassable and sometimes even forestall offloading fish.

“We’re playing this game of chess. How much fish do we have coming in, and what vessels can we get them on and how much water do we have coming in and out of Bristol Bay?” Benson said.

Trident is one of more than 30 companies that processed the harvest. Many are based in Naknek, a small community where seafood companies have built bunkhouse campuses to lodge and feed their workers.

At Trident, some 400 men and women pulled marathon 16-hour daily shifts to keep pace with the processing of the salmon stowed in a long row of chilled tanks, each of which can hold 49,000 pounds of fish.

“We need all this capacity to get us through the next tide when we can take in more fish,” said plant manager Luke Forrestor.

Some fish were filleted or flown out by plane for fresh markets. Most ended up as headed and gutted, frozen then shipped by sea to U.S. markets.

Toward the end of the season, it appeared shippers might run out of freezer containers. But a series of storms slowed the fishing effort, which ended at the tail-end of July as Trident and other processors stopped buying sockeye.

By then the total harvest had reached 59.5 million fish—26% more than had ever been caught in a single Bristol Bay season. That was enough fish to serve a quarter-pound of salmon to every person in America.

In the 1940s, when the catch dipped as low as 4.7 million salmon, the gargantuan scale of 2022′s summer harvest would have seemed like the stuff of science fiction.

Industry officials worried about the weak returns and were frustrated by then-federal management. They wanted fresh research that could yield a better account of the runs, a more accurate forecast of the next year’s harvest and more assurances of a sustainable harvest.

So in 1946 the Bristol Bay canneries gave the University of Washington $36,000 to take a closer look at the salmon runs. More than 75 years later, the industry grants, along with other funding, still support the university’s salmon research.

This has enabled generations of scientists and students—based out of a network of backcountry camps—to produce a remarkable long-term documentation of the freshwater ecosystem that sustains the sockeye.

At a remote shoreline site at Lake Nerka, a log cabin erected in 1949 is surrounded by more than a half-dozen other structures, including bunkhouses and a cookhouse near a garden patch of arugula and rhubarb.

UW’s Schindler first came to this camp in 1997 and has been back every year in a season that now starts in late May and runs through mid-September. During the height of spawning season, he may wade 6 miles or more a day to count salmon in the creeks.

Through years of observations, Schindler and other UW researchers have documented some startling adaptations.

In one shallow creek, the salmon that return are smaller and narrower than most Bristol Bay sockeye. These sleeker bodies give them a better chance of scooting across a gravel bar entry often covered with just a few inches of water, without flopping over or getting picked off by bears.

About half the Wood River drainage sockeye forgo creeks to spawn in the gravel beaches of nearby lakes. Those salmon often have bigger bodies since they spend their final days where the water is deep enough to offer more protection.

“We’re always humbled by not how much we know, but often how little we know,” Schindler said.

Schindler and other fishery scientists have looked to the freshwater and oceans for clues to the runaway sockeye returns of 2022, which by late July offered startling vistas of vast schools milling about patches of Lake Nerka’s blue-green water.

UW research records track a long-term warming trend that has resulted in the breakup of lake ice about two weeks earlier now than in the 1950s, according to Schindler. This increases the food supplies for young salmon, which, after they hatch, live in freshwater for one to two years.

But the biggest reasons for the record runs appear to be in the ocean, where they spend one to four years before returning to spawn.

Ed Farley, an Alaska-based federal scientist, helped to pioneer the study of Bristol Bay sockeye in a series of research cruises in the southeastern Bering Sea between 2001 and 2015. He sampled the fish during their crucial first year in saltwater when they must grow fast and accumulate fat to survive the winter. His studies consistently found more young sockeye during years with warmer temperatures in the southeast Bering Sea than in cooler years.

Farley said that in warm years, sockeye ranged farther offshore and shifted more of their diet from zooplankton to very young pollock, a fish found in great abundance.

In 2019, Bering Sea surface temperatures climbed as much as 9 degrees above the long-term average, according to an analysis of federal readings by the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The young sockeye that encountered those conditions appeared to thrive, as they formed a big portion of the adults that returned to produce this summer’s record Bristol Bay return.

“These warming events have been very positive for the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon,” Farley said. “They grow pretty quickly early on, and we see a lot of them out there in our surveys.”

During their years at sea, the Bristol Bay sockeye forage as far west as coastal areas off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula and south into the Gulf of Alaska. During the past 70 years, this vast swath of the North Pacific has become more crowded with salmon due, in part, to a dramatic expansion in Asian and North American hatcheries.

In 2018, more than 5.5 billion hatchery salmon, mostly the fast-growing, short-lived pinks and chum, were released into the ocean—a more-than-ninefold jump from the 1960s, according to Greg Ruggerone, a Seattle-based fishery scientist who has studied both freshwater and ocean salmon for decades.

Ruggerone said that the big increase in the hatchery salmon, along with surging numbers of wild pink salmon in a warming ocean, have intensified competition for food in the North Pacific. Some wild runs of the longer-lived and larger kings—also known as chinook—have declined not only in the Yukon and other western Alaska rivers but also in many other North American drainages.

These changes also may help to explain a steady decrease in the adult size of Bristol Bay sockeye.

During this summer’s harvest, the average sockeye that spent three years at sea weighed 5.54 pounds, nearly 17% below the long-term average, according to sampling by Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game.

“It’s quite significant,” Schindler said. “We know that smaller females have fewer eggs and smaller eggs. So big females are worth a lot from a reproductive standpoint.”

In July 2019, a heat wave hit Bristol Bay that offered a stark foreshadowing of the kind of summers that could become the norm later in this century.

Salmon can die if exposed for prolonged periods to temperatures above 68 degrees. The temperatures at the mouth of Bristol Bay’s Igushik River in 2019 climbed past 70 degrees, according to readings taken by skipper Camron Hagen.

Hagen observed thousands of sockeye milling in the tidal waters near the river mouth, and many perished long before they could swim upstream to spawn.

“The beaches were covered with dead fish,” Hagen said. “I’ve never seen anything like that.”

Alaska state fish biologists confirm that thousands of salmon died from heat stress during the summer of 2019, but note that millions of sockeye still made it to spawning grounds around the bay.

“It wasn’t like we’re losing our spawning production because of this heat wave. But it was obviously killing fish,” said Travis Elison, a state district biologist.

Elsewhere, broader impacts to sockeye runs have been linked to prolonged heat waves. The Gulf of Alaska, which even in normal years typically has higher temperatures, saw intense warming in 2015-2016 and again in 2018-2019.

In a warming sea, why does the world’s biggest sockeye run keep breaking records?

Some runs of Alaska, Canadian and Northwest sockeye, which feed in the Gulf of Alaska, plummeted during this period. In 2020, for example, Canada’s Fraser River sockeye hit the lowest point on record with a run of fewer than 400,000 fish.

During the past two years, the Gulf of Alaska temperatures have cooled. And in 2022, sockeye populations in Canada and the Pacific Northwest rebounded.

On the Columbia River, as of Aug. 24, 663,174 made it past Bonneville Dam east of Portland, most headed for Canada — the biggest run since 1938.

But climate models forecast that the warming periods in both the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea will become more frequent and severe as the ocean absorbs more heat amid the buildup of atmospheric greenhouse gases.

“This is where we are headed. The temperature could spike again,” said Nathan Mantua, a federal climate scientist who studies salmon.

Still, in this summer of bounty, Schindler in his forays through streams finds reasons for hope. These salmon are stubborn, resilient creatures.

He pointed to a sockeye with a fresh, deep wound from a bear bite. The fish, still alive, would likely fight on to try to spawn.

If more creeks get too hot in July, Schindler expects sockeye can spawn in those waters later in the summer when the temperatures ease.

If entire rivers get too warm, then sockeye might evolve to come back to Bristol Bay earlier, in a cooler month.

But how much—and how fast—can the Bristol Bay sockeye change as greenhouse gases increase in the atmosphere and set the stage for more heat waves?

“In the watersheds, they have lots of options to do what they need to do to survive,” Schindler said. “In the oceans, they may not.”