What are the effects of being born of rape in the name of genocide? How are mothers who survived this brutal violence in Rwanda dealing with the trauma and complexities of their lives and the long-lasting, multigenerational impact of what was done to them?

In 2018, I returned to Rwanda to revisit some of the families I met 12 years before when I began a project documenting the stories of women who were raped during the 1994 genocide and the children born of those horrific encounters. The mothers have now disclosed to their children the circumstances of how they were conceived, and the children are speaking for the first time as adults, reflecting on being called “children of the killers” while they were growing up.

Between April and July 1994, an estimated 800,000 people, a vast majority of them members of the country’s Tutsi minority, were killed in the space of 100 days in the small central African country of Rwanda by Hutu militias known as Interahamwe. Thousands of Tutsi women were violently and repeatedly raped. Thousands of children were conceived during those rapes; many of their mothers contracted H.I.V./AIDS during the same brutal encounters that left them pregnant.

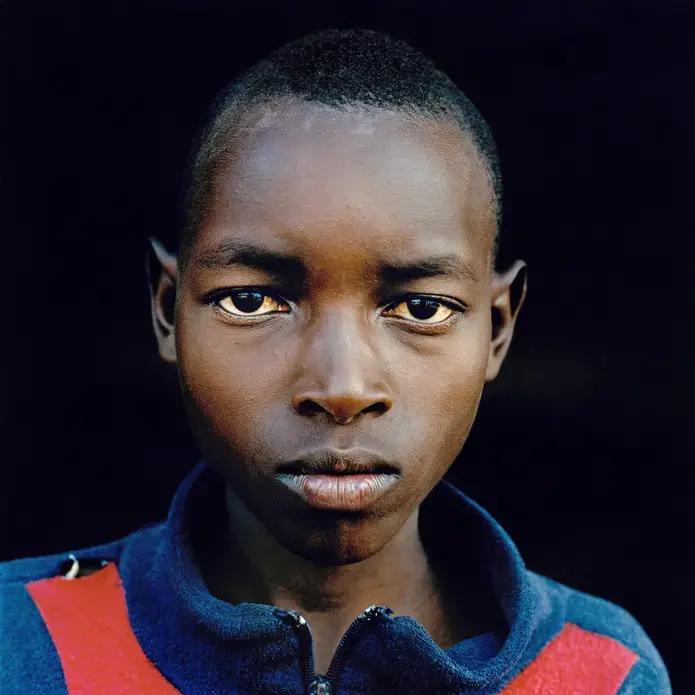

Rwanda’s children born of rape have come of age. At 24, these young men and women are reflecting on what it has meant to be born of such awful circumstances and the isolation they endured as a result. They are sharing the challenges they face as they become young adults in a judgmental society that adheres to traditions and rules that make it difficult for them to avoid discrimination and harassment. “When my mother told me about how she was raped, I felt like something was piercing my heart,” said Faustin, whose mother, Bernadette, was hung from a tree and raped multiple times during the genocide. “I felt a lot of pain knowing I was born as a result of my mother being raped and my father was a rapist and killer.”

“I used to feel bad knowing that my father is a killer and rapist, and I used to feel stigma about being born from a person that killed people. We all want to be identified as good people, and being identified as the son of a bad person used to hurt me very much, but most recently I decided that I consider him as never having existed, like he is not my father.”

— Thomas

Some of their mothers have made progress in their healing process in the years since I last visited them. Faustin’s mother, Bernadette, testified against his father in court. After that, she said: “One day he came to my house, knelt before me and pleaded for me to forgive him. I reflected on how many women were raped, and after being raped, killed. But I was raped and he did not kill me, so I found it was good for me to forgive him.” But today, she says, her son faces unfair discrimination because of what his father did: “I was so traumatized and disturbed by the fact that my son was referred to as ‘child of the killers’ in my community.”

“One day I called my daughter in to my bedroom, and I told her: ‘You know that during the genocide many people were killed, and many women were raped, and you may have heard that there are many children that were born as a result of the genocide. I wanted to tell you that during the genocide I was raped and as a result I gave birth to you, and I don’t know who your father is because there are many men that raped me.’ After I told her this, she kept quiet, so I didn’t want to continue because she was shocked about what I had told her. My relationship with my daughter improved after I disclosed to her. Before I disclosed to her, I did not feel much love for her, but after I told her the circumstances of how she was born, I felt more love for her.”

— Justine

“The fact is, my father was among the killers and did things worse than animals can do. I would not want to identify with him, I don’t think he is a normal human being. … The effects on me are that I feel that my father contributed to the horrible things that happened in Rwanda, and I don’t feel good about having been born from someone like that. Life has improved and is still getting better. I have completed secondary school and started university, and I am a strong young woman. I used to be so sad. Now I feel free.”

— Alice

“My mother called me to the house and we sat down, and then she started telling me how I was born as a child of a killer and the man who raped her was a Hutu, and that she had no role in having me with this man but it was forced and that this man was not good, he killed many people, but my mother loved me as who I am, as her child. I broke down after she told me this and I cried and was traumatized. After she disclosed to me, I hated that man that was my father. I don't think I would ever forgive him. One of the effects of knowing I was born from genocide rape is psychological. I felt I was unwanted. Another effect is that I have no family, I only have my mother. The fact that my mother disclosed to me that I was born from genocide rape made me increase my love for her. I know what she went through was not her fault.”

— Robert

“I told my son, I am his mother, I am his everything and I am committed to living with him for as long as I can. After I told him all this, he was very sad. He then asked me: ‘Did people really take machetes and cut people and kill people and rape women? I can’t believe what really happened.’ I told him it was true, that Hutu people killed Tutsi people.”

— Valerie

“My message to the world today is: “I wish genocide not to happen anywhere, that it is the worst thing that can happen to an individual, to lose all your family, and the effects go on and on for generations. … Rape was the greatest weapon during the genocide, because the people that were killed died, but us that were raped, we live with the consequences, and then we pass those consequences to the next generation.”

— Stella

“When she told me this I felt bad, but I got courage to realize that I will not be defined by the way I was born, as a young person born from rape, but I want to build a good future and be a responsible person in my life, and not be looked at as a child born from rape. The effects of how I was born on my life are having shame and stigma. It makes me feel shame that my father had a role in killing people, and raping my mother, but I wish I had an opportunity to ask him what made him do all these things. He died before I had a chance to meet him.”

— Claude

“When growing up, my stepfather treated me differently; he refused to pay my school fees, so I was working as a house girl doing all the housework while my sister and brothers that were his kids were at school. My stepfather would punish me like he wanted to kill me. He would call me ‘good-for-nothing child.’ Whenever I was told those bad words, I would go and sit somewhere. I would write sad things about my life, I would write songs, but songs of sadness. I preferred to be alone, in isolation, and write in my book.”

— Elizabeth

“I told my daughter that during the genocide, I was raped by a Hutu militia, and as a result she was born. My daughter seemed to be traumatized for a few minutes, then she was quiet for a while and then she stood up, hugged me and said, ‘I forgive you for not telling me before,’ and I hugged her and we cried together. She just kept saying, ‘I forgive you, I forgive you.’ I felt a sense of relief, because not telling her the truth was always a burden to me, and now this burden was gone.”

— Clare

With this project, I’m hoping to shed light on the underreported issue of rape as a weapon of war, and its consequences: the children born of rape in conflict areas and the complex and deep trauma they live with for their entire lives and that continues for subsequent generations. Revisiting the families, I found challenging stories of hope and forgiveness. But I also found fragility and lingering trauma, among mothers and children alike.