This article was also translated into French and published by Ulyces.

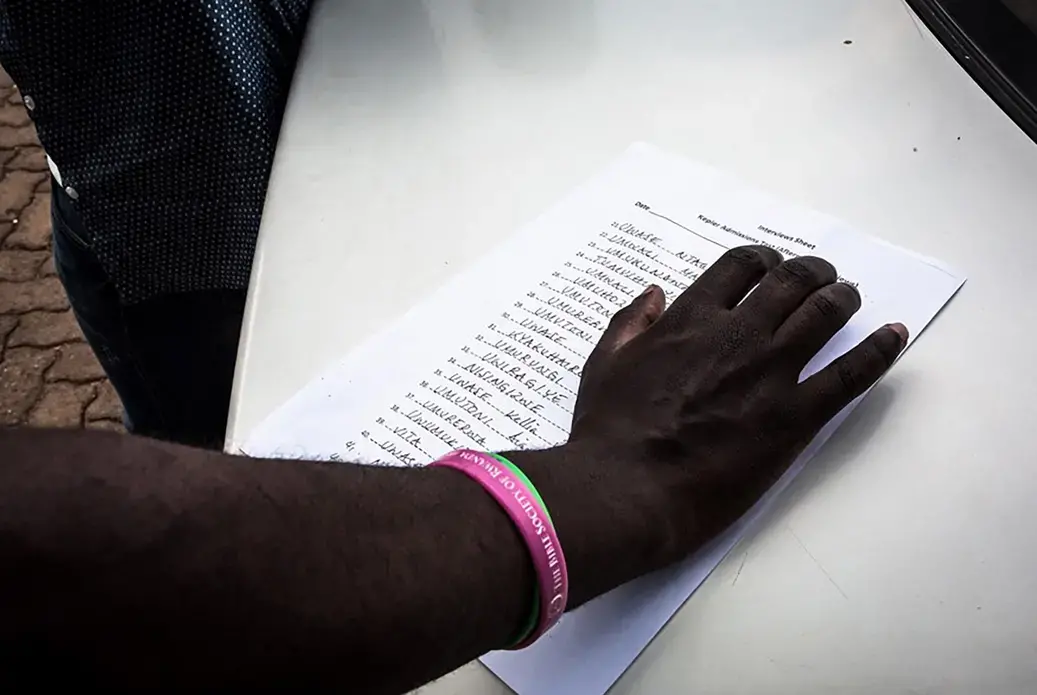

Under a bright, midday sun, a large group of prospective college students waits in the parking lot outside Kepler University, in the Rwandan capital of Kigali. The results of the morning's admissions tests will soon be taped to a large window next to the school's entrance. For many of those waiting, acceptance to Kepler could mean an end to their poverty. One young man, who cleans dishes at a hotel to support his family, says earning a spot here would be the "first happiness in [his] life."

The student hopefuls stand and sit in small groups and speak to one another softly; their conversations are mostly drowned out by noise from nearby construction sites. Everyone appears calm, even though just a third of those who took this morning's exam will advance to the interview stage after lunch. When the results are posted, our man learns that he's not one of them.

Kepler has been testing groups of applicants like this around the country for the past month. This year, they received around 6,700 applications for 150 spots, which puts their acceptance rate at roughly two percent. Last year, Harvard's undergraduate acceptance rate was triple that, at six percent.

The university, which opened in 2013, takes its name from Johannes Kepler, the influential 17th century astronomer who overcame severe childhood sickness to later discover the laws of planetary motion. Kepler University's ambitious aim is to provide "an American-accredited degree, a world class education, and a clear path to good jobs" to Rwanda's most needy for $1,000 per year (roughly the same cost as local universities).

Such bang for the buck requires serious penny-pinching. The campus, for example, is a renovated, three-story office building in a loud neighborhood on the outskirts of Kigali. "When trucks go by the windows shake," said Kepler's CEO, Chris Hedrick, "but that's part our cost structure."

The university is an iteration of an organization called Generation Rwanda, which started a decade ago as a scholarship program for orphans of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. It sent dozens of extremely disadvantaged students to local universities each year, while simultaneously providing them career training. But when they looked to expand, it proved too costly. Kepler was born out of the search for a more affordable and scalable higher education model.

To get the project off the ground, Kepler turned to the IKEA Foundation. The philanthropic arm of the Swedish furniture giant agreed to fund the university with a one-year pilot grant that has since been extended into a four-year, $8 million commitment. Among other things, this support has made it possible for Kepler's first two classes to attend on full scholarships.

According to Foundation spokesperson Jonathan Spampinato, both Kepler and IKEA "look for ways to create better everyday lives for many people by lowering costs while keeping quality."

Ensuring their education is both high-quality and affordable is a balancing act that Kepler is still perfecting. Classroom time with professors is a pillar of traditional higher education, but comes at a high cost. Online classes, on the other hand, are cheap — even free — but their completion rates can be dismal, often less than 7%.

Kepler's challenge is to effectively and efficiently meld these two models — commonly referred to as "blended learning." It's one of a handful of universities doing this in the developing world.

The university uses what it calls a "flipped classroom." At night, students often watch online videos — known as MOOCs ("mooks"), a goofy acronym for "Massive Open Online Courses" — which are culled from universities mostly in North America, Europe, and Australia. At school the next day, they attend class with a course facilitator who helps them work through the material.

On Fridays, a group of a dozen or so second-year students meets to talk about business strategy. On one particular Friday, they came having watched videos on "capability analysis." The course facilitator convened class with a short overview of how the day's material fit into the class' broader study of competitive advantage, or how businesses outperform others. Once he finished, the students divided into discussion groups.

In one group, Joyeuse Muvandimwe told two peers she thought capability analysis referred to when a company develops ways to attract and retain customers. Her partners nodded in agreement. "The uniqueness that you have in your company," offered another young woman. "But how do you create uniqueness?" A young man chimed in, saying he thought companies simply need to do what others aren't doing. Both women looked at him skeptically and the conversation continued.

All the while, the facilitator worked his way around the room, listening in here and taking part there. After half an hour, he asked one group to present a synopsis of the discussion they'd had.

Many students here will tell you this is the first time discussion has been a formal part of their education. The other Rwandan universities, they say, are lecture-based, with large class sizes. Kepler students overwhelmingly prefer this new pedagogy, which they see see as enhancing their critical thinking.

This Friday group, however, isn't what earns the students their diploma. Neither is the Kepler-designed writing workshop, finance class, or book club, where students just finished reading The Hunger Games. While these courses provide foundational knowledge and skill development, Kepler students ultimately get their business degrees from Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) by meeting a set of specific benchmarks, or "competencies." These are defined by College for America (CfA), a SNHU-affiliated non-profit that uses blended learning to provide college education to working adults in the US.

Examples of CfA competencies include "create and use a budget" and "write a business memo." If a student masters the competency, according to CfA evaluators in the US, they continue to the next one. If not, they try again; 120 competencies are required for an Associate degree and 120 more for a Bachelor's. Every student progresses at his or her own pace, but if a student is taking exceptionally long, Kepler staff are likely to intervene and offer additional support.

Speed, though, hasn't been issue for students. According to Hedrick, "They're moving along faster in earning their degrees than [at] just about any other institution of higher learning in the US." Motivation is incredibly high — sometimes to a fault, Hedrick suspects, because students stress themselves out.

The financial reality is that they "can't always learn for the sake of learning," said Chrystina Russell, Kepler's Chief Academic Officer. Their concerns are much more immediate. "They want a job. They're telling us very directly, they want to come out of poverty."

Kepler has yet to graduate its first class, so it's too early to tell whether the education will give way to steady employment. By most accounts, though, the school has made enormous strides in its first two years. Forty-nine of fifty students in the first class are on track to earn their Associate of Arts degree this June; the one exception is a female student whose graduation has been delayed by pregnancy. Kepler has engaged an independent data analysis firm to track student progress, so the model can be nimble as per student needs.

That said, no one at Kepler is under the illusion that they've perfected the system yet. "We're building this airplane as we're flying," said Hedrick.

English proficiency has been a constant hurdle. This is due, at least in part, to the government switching the official language of instruction from French to English in 2008, which left many in the country in linguistic limbo. The hope is incoming students' level of English will eventually improve. The Kepler staff estimates they currently spend as much as a quarter of their time addressing language issues.

A bigger question is how effective course facilitators can be without subject-area expertise. "I did not study economics," said lead facilitator Aurore Umutesi, "but I've taught macroeconomics and microeconomics." Using generalized instructors, who act more as guides than as teachers, saves money. But students like Sereverien Ngarukiye can find it frustrating. "[It's a] challenge when they're also not able like to explain the full content."

It's unclear what qualifies Kepler's facilitators in the first place. Command of English and familiarity with Rwanda (almost all the facilitators are Rwandan) are paramount, said Russell, but after that, it gets murkier.

"We don't look for skills that teachers come in with, as much as a willingness to be innovative," she said. Kepler tries to round out the staff with a range of backgrounds. The school has even started experimenting with using students as teaching assistants, precursors to the course facilitators. "We're confident that Kepler [students] will be our biggest pool of talent for hiring once they graduate."

Although finding quality teachers at a low cost is a perpetual challenge for blended models like Kepler's, Dr. Mark Brown, who directs the National Institute for Digital Learning at Dublin City University, cautions against underestimating the importance of educators. "It's not always a particularly popular view in today's age," he said, but especially at advanced levels, "education does require knowledge."

Beyond retaining skilled teachers, his broader criticism of blended learning is actually that it isn't transformative enough. He contends technology is being used to merely "tinker toward utopia" rather than fundamentally change how students learn. MOOCs, for example, still largely come in a lecture format from predominantly Western sources, which, Browns says, risks "dump[ing] a Western curriculum on parts of the world that probably, desperately, don't need that." However, if Kepler is indeed providing young Rwandans greater access to education and employment, he sees their approach as a creative step toward meeting local needs.

"If someone is teaching you how to swim and brings you a book, you're going to drown," said Kepler student Shanton Ngabire, describing how the Kepler's approach is unique in Rwanda. "They teach you how to swim in water."

That said, Kepler's adaptation to the local environment is far from over. The administration team in Kigali, which is entirely American, would like to see Rwandans take the reins in the next few years. And, if Kepler continues to succeed, it could be a harbinger of a new higher education model in the developing world. With support from IKEA, Kepler is already considering applying their self-described "university in a box" approach elsewhere. A potential satellite campus in a Kigali refugee camp, for instance, could serve as a stepping-stone to other parts of East Africa and beyond.

The task at hand, though, is ensuring that the existing Rwandan program is sustainable. This will mean reducing per-pupil costs, which are still relatively high, so the school can make ends meet when the IKEA money runs out. This is going to require risky steps, like charging tuition, reducing the number of expensive foreigners on staff, and increasing enrollment.

As the sun went down on a recent Wednesday, students filed back to their group houses, which are between a ten and twenty minute walk from campus. Some strolled from class, backpacks slung over their shoulders. The ones out running with the marathon club should be back any minute. Some were using the last light to wash their clothes behind the houses.

Sereverien Ngarukiye lives with fifteen classmates. The setup is not without its problems — today the electricity is out, other times it's the Internet — but still he's more than content.

"Two years ago, I was not imagining that I can be in such [a] good place," he said. He can now type 50 words per minute, use Microsoft Excel, navigate Google Drive, properly cite his work, and much more. All of these skills, he said, put him ahead of his high school classmates who entered other local universities. What's more, those same non-Kepler friends are envious of his living situation.

Past the dining room and up the stairs, Ngarukiye entered the small room he shares with three peers. Clothes and books were strewn about the bunk beds, with only a small balcony to escape the clutter.

In June, Ngarukiye will be halfway to a Bachelor's degree. He paused to reflect in the twilight. "I'm really proud of where I am now."

Education Resource

Meet the Journalists: Tik Root, Wyatt Orme and Juan Herrero

Tik Root, Wyatt Orme, and Juan Herrero speak about their project in Rwanda where they explored the...