In India, strides are being made to increase access to contraception, but plenty of challenges still exist—especially when it comes to reaching rural women. And too often, women bear the burden of family planning. In fact, among developing countries, India has the highest number of women—31 million—with an "unmet need" for contraception, according to RAND survey research.

Doctors, educators and advocates are trying to turn that around. They've tried piloting a device that helps couples track fertility, encouraging larger family discussions and developing a reversible contraceptive for men, as just a few examples.

Tracking fertility with CycleBeads

Maybe you’ve never heard of the Standard Days Method, but about 2 million women around the world use it. It’s a calendar-based method of birth control. You don’t need to swallow or insert anything. But you do have to pay close attention to what you’re doing for it to work.

The Institute of Reproductive Health at Georgetown University developed a device called CycleBeads as a way for women to follow the Standard Days Method. CycleBeads resemble a necklace with brown and white plastic beads, with one red bead that marks the first day of a woman’s menstrual cycle.

You track your fertility by moving a rubber band on the beads each day. Beads that mark “unsafe” or potentially fertile days glow in the dark, so you can see them at night without lights.

That's important in places like India's rural state of Jharkhand, where many villages don’t have electricity. An ambitious pilot program for CycleBeads took place in Jharkhand, where over 1.5 million women are at risk of unwanted pregnancy because they don't use birth control.

"You just have to keep talking about the safe and unsafe days. When you do and you’re both careful, there's no danger of an accidental pregnancy."

Shabnam Thirki, CycleBeads user, Jharkhand state, India

Anughram Thirki remembers his wife, Shabnam Thirki, talking about CycleBeads. The couple has been using the device for five years. Shabnam Thirki says it works as long as couples communicate. "You just have to keep talking about the safe and unsafe days. When you do and you’re both careful, there's no danger of an accidental pregnancy," she said.

But that kind of conversation isn’t easy for some couples. And critics say CycleBeads depends too much on a woman’s ability to say no to her husband. The pilot program ended in 2016, but people here still talk about CycleBeads.

Also, Jharkhand piloted another program that helps families talk about contraception: It's called Saas Bahu Pati Sammelan, which means “meeting of the mother-in-law, daughter-in-law and husband.” In many rural families, the mother-in-law has influence over how many children a couple has. This program encourages families to discuss it together.

Controlling the population

When Pinki Sahu heard her sister, Sunita Sahu, was in the hospital due to complications from surgery, she got there as quickly as she could.

Sunita Sahu was 25 years old. And the procedure she was getting—tubal ligation—should have been straightforward. Pinki Sahu never imagined it could lead to her sister’s death. It was November of 2014. And like many women in rural parts of India, Sunita Sahu had gone to a government-run surgical camp set up to sterilize large numbers of women.

Women in rural areas would line up for tubal ligation—and get paid a small fee. On the day Sunita Sahu went to the camp in Bilaspur, the surgeon performed the procedure on 83 women.

Sunita Sahu was one of 14 women who died from complications. All had young children.

Human rights lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj says it’s no coincidence so many women like Sunita Sahu lost their lives that day. "We place the entire burden of controlling the population on very poor women, and we're fairly callous about the way we treat them."

India was the first government in the world to launch a program aimed at controlling its population. It’s run radio and TV spots urging married couples to use contraception. The scandal wherein Sunita Sahu died and ensuing investigations ultimately led India to ban mass sterilization camps in 2016.

But that’s created a new problem for poor women in rural areas. Many who want the procedure can’t find a place to have it done.

Dr. Yogesh Jain works about 25 miles from the sterilization camp that led to the changes. And he says that his hospital can’t keep up with the demand. They’re overwhelmed.

Advocates say whether you’re targeting a certain number of women for sterilization or leaving them without options, you end up compromising community health. They say India doesn’t need top-down population control. It needs to make people aware of the benefits of contraceptives and make them available with good quality care.

A reversible contraceptive for men

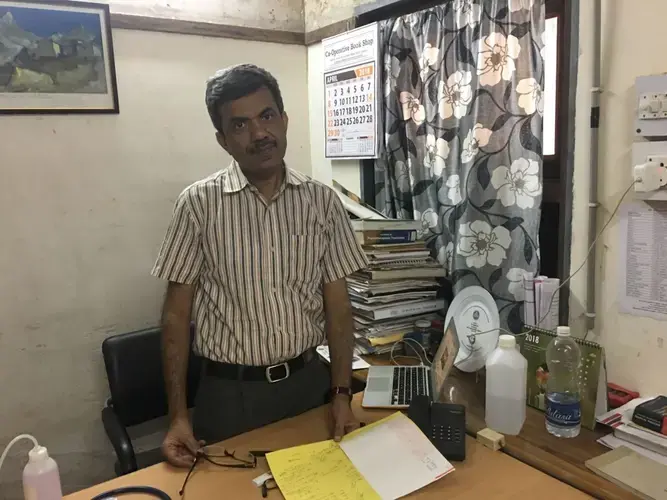

Another doctor in India, Sujoy Guha, based in Delhi, has worked for several decades to make male contraception a reality.

Guha, also a biomedical engineer, developed a reversible contraceptive for men called RISUG (Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance). Here’s how it works: a gel is injected into the vas deferens, and renders sperm ineffective so they can’t fertilize an egg. And if a patient decides he wants to have kids later, another injection breaks down the gel.

In 2000, when RISUG was ready for human clinical trials, it was tough to find volunteers—in India, family planning and childbearing is still seen as the woman’s responsibility.

“Women generally do not like their husbands to get into any kind of medical procedure. They would much rather feel that they would take all the burden. But that is changing now. The male is starting to feel that they should be equally responsible in what we call ‘family welfare.’”

Sujoy Guha, doctor and biomedical engineer, India

“Women generally do not like their husbands to get into any kind of medical procedure. They would much rather feel that they would take all the burden. But that is changing now. The male is starting to feel that they should be equally responsible in what we call ‘family welfare,’” he said.

Guha wants to do another clinical trial to ensure that the drug will be available in rural areas and not just urban centers. It's unclear where the funding for it will come from but he’s patient. After all, this has been his life’s work for the past four decades.