Plumes of smoke trailed behind a fleet of excavators and bulldozers mounding downed debris within a protected forest that they were ordered to clear just a few days earlier.

Several metre-high piles of trees made it easier for Kem Khim to harvest timber, which she intended to use for firewood and fencing. Each swing of her machete grew the stack of wood she planned to carry to her nearby home.

A combination of heavy machinery and a hundred or so residents were clearing the way for rapid reforestation. By the end of the first day, thousands of saplings for luxury-grade timber were freshly planted.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

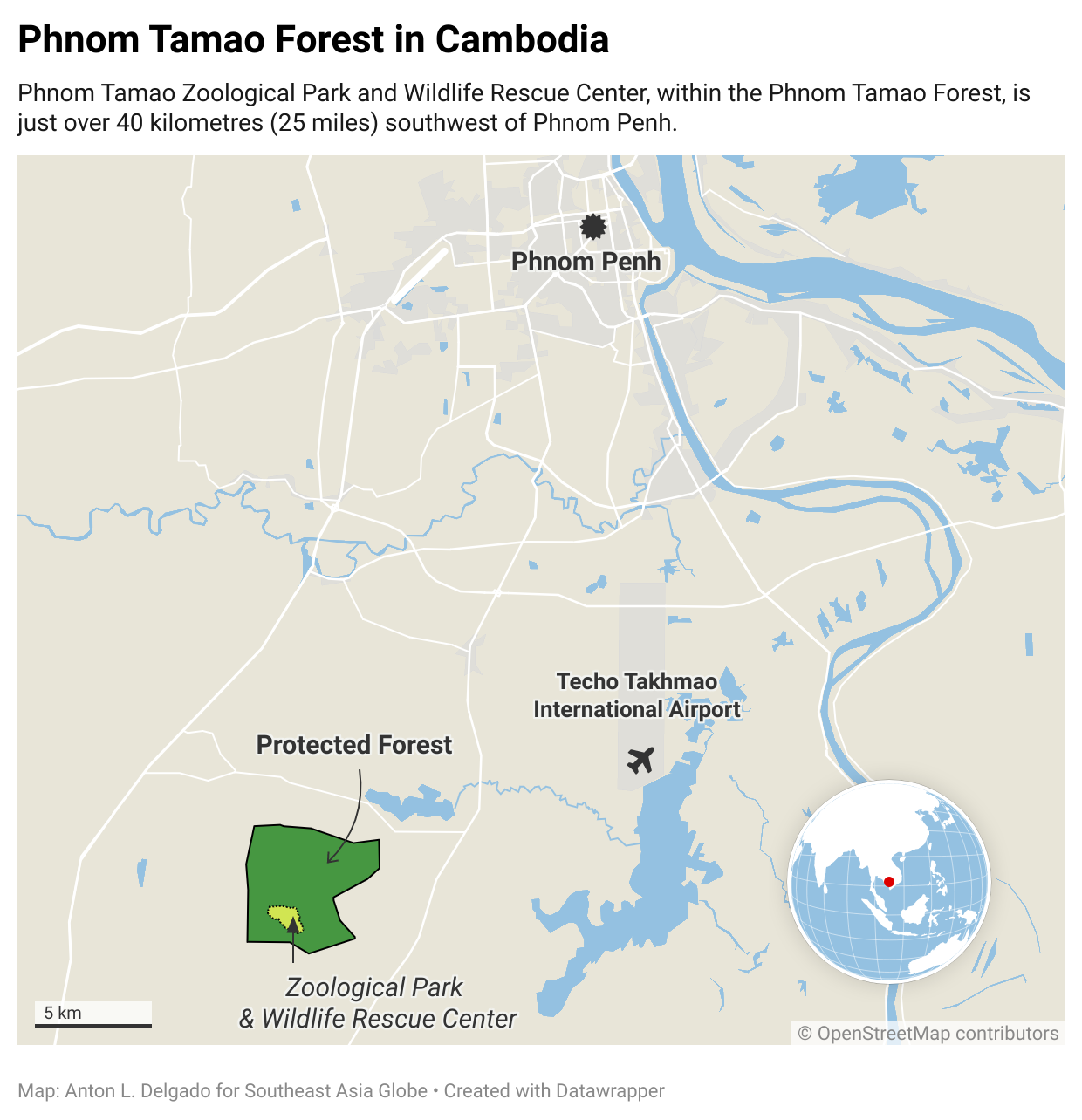

The launch of the reforestation campaign closed out a week that began with huge swathes of trees cleared from Cambodia’s Phnom Tamao Forest. Just days before, the area was destined to be developed into a satellite city that drew extensive criticism until Prime Minister Hun Sen cancelled the clearing following a social media tempest.

“It was public support and the intervention of the prime minister that saved Phnom Tamao Forest,” said Nick Marx, director of wildlife rescue and care with conservation group Wildlife Alliance. “Whether this would happen elsewhere in the country I could not say.”

The developers and government ministries overseeing the land exchange are now being praised for saving what is left of the protected area and financing reforestation, even though the change in policy was a result of the unexpected order from the prime minister.

Experts worry a rushed reforestation may not lead to full ecosystem recovery for the forest, which surrounds a wildlife rescue centre and was used to release animals.

But after the sudden change of plans, activists, conservationists and political analysts are left to ponder the peculiar case of Phnom Tamao.

Optimists hope the prime minister’s response indicates the government’s renewed commitment to sustainable resource management. Pragmatists gauge whether this is a conservation case study for the necessity of online support to save protected areas. Sceptics believe the government’s actions are performative, especially in the lead-up to Cambodia’s national election in July 2023.

Pushback at Phnom Tamao

Land exchanges within the forest were debated from the beginning. And developers and government officials remained tight-lipped about the intended use of the protected area.

But a murky mix of leaked documents, social media posts, and billboard advertisements indicated a plan to construct a new satellite city in close proximity to Cambodia’s newest international airport, which is set to be completed in 2023 and linked to Phnom Penh, just 40 kilometres (25 miles), by a recently renovated national highway.

Wildlife Alliance and other conservation groups including Fauna & Flora International and Free the Bears worried about the future of Phnom Tamao Zoological Park and Wildlife Rescue Center, which would have bordered the development. They were also concerned for the wellbeing of hundreds of rescued animals released into the forest over the past two decades.

Despite the opposition, satellite imagery confirmed by ground photos taken by Wildlife Alliance, show small-scale clearing began on 31 July. The following days saw a boom in operations with up to 600 hectares (1,482 acres) cleared within the first week of August, according to an estimate based on satellite imagery and ground observations.

The speed and scale of the clearings caused a shock-and-awe response on social media. Videos of the levelling along with hashtags such as #SavePhnomTamao reached thousands of people online within the first day.

The Forestry Administration, which manages Phnom Tamao Forest as part of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, fuelled the digital backlash by defending the project with a statement that claimed there were no endangered species in the forest and that wild animals were a nuisance to farmers. A claim Marx and monks at Wat Tmor Antorng within the forest vehemently said was false.

The director of the Forestry Administration, Keo Omaliss, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Nhek Ratanapich, director of Phnom Tamao Zoological Park and Wildlife Rescue Centre, declined to comment.

Less than a week after clearing began and as the number of shares, comments and articles about Phnom Tamao steadily rose, a Facebook post by Hun Sen, whose Office of the Council of Ministers greenlighted the land exchange that opened the forest to development, brought bulldozers and excavators to a grinding halt.

The Prime Minister’s social media post, which effectively became law, cancelled the land exchange and development permits within the protected area. The online directive also returned jurisdiction of the land to the ministry with instructions to protect the forest around the zoo and rescue centre.

Hun Sen further instructed companies to stop clearing operations and reforest the bulldozed areas. He said there were “many requests to the royal government to keep the forest,” and even thanked those who shared “constructive comments.”

The post does not indicate how long the orders will be in effect. While Marx had seen no official documentation other than the post, he felt secure saying “Phnom Tamao Forest is now safe.”

“The public feeling was so strong that the prime minister intervened to save the forest,” said Marx, whose videos pleading for Phnom Tamao to be saved received tens of thousands of views. The clips have since been removed from Wildlife Alliance’s Facebook page and replaced with a video thanking the prime minister and the public for saving the forest.

Khim, who has lived in Kandoeung Toch village on the border of Phnom Tamao all her life, said she had never before seen an attempt to develop the area.

“I hope this is the last time someone tries,” she said. “I am relieved the project was stopped before more of the forest was lost. I saw the tree planting begin and I will hopefully get to see those trees grow big, though I think it might take a long time.”

Alongside dozens of her neighbours, Khim spent the first few days after the development was cancelled collecting wood from cleared areas. Motos, minivans, remorques and even an ice cream truck stacked with tree limbs jammed the single-lane, sandy road leading to the northeastern edge of Phnom Tamao.

“They already destroyed this part of the forest, so there is nothing for us to do but take the wood, since the trees are sadly already dead,” Khim said.

Ly Chandaravuth, an activist with Mother Nature Cambodia, who helped organise in-person and online campaigns to save the forest, acknowledged the impact of activist campaigns, news articles and social media comments, while noting another important factor.

“Cambodia has a national election in 2023 and that played a big part in Hun Sen’s decision to save the forest, which also saved popularity for the ruling party,” he said.

Sam Seun, a political analyst at the Royal Academy of Cambodia, agreed the prime minister’s decision brought “good fame” to the Cambodian Peoples’ Party, especially among the Kingdom’s internet savvy demographic.

“We have so many young people in Cambodia and almost all of them are social media users,” Seun said. “Social media has such an impact because that is where people receive news and where good or bad fame is spread.”

With Cambodia’s median age in the mid-20s, “It is important for the ruling party and other political parties to understand how to get the support from the young generation, from the social media users,” Seun said.

Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, welcomed “this small victory” but feared the “prime minister’s intervention is but a one-time occurrence” prompted by public outcry, rather than representative of a shift in government priorities.

The order to replant in bulldozed areas of Phnom Tamao was posted just past 10 am on a Sunday morning. By 8 am the next day, reforestation had begun.

Replanting in Phnom Tamao was first mentioned on Facebook by real estate tycoon Leng Navatra, who was one of the developers responsible for clearing the forest. Less than 15 minutes before the prime minister’s crucial post, Navatra reached out on Facebook to “all those who love trees” to join him at Phnom Tamao.

In the week leading up to Navatra’s newfound green thumb, a hashtag bearing his name – #BoycottNavatra – circulated online as part of public discontent. Months before clearing began, Navatra, who leads companies including China Poipet Satellite City and Galaxy Navatra Group, met with local officials to finalise the land measurements of his allotted portions, the Forestry Administration confirmed.

Since the directive restored forest protection, Navatra has committed to donating about a thousand saplings to replace the trees his heavy machinery toppled.

“If they were passionate about the forest and wanted to keep it the way it was, they shouldn’t have cut it down in the first place,” Chandaravuth said. “People have been against the land exchange since the announcement. They should have consulted with civil society and people, they should have listened to public opinion.”

The prime minister gave permission for agricultural tycoon Mong Reththy to take the lead in reforestation efforts. Reththy plans to reforest the 500 hectares (1,235 acres) he said had been cleared.

An official from the Mong Reththy Group confirmed newly planted saplings were of three luxury timber species: Dalbergia cochinchinensis, Afzelia xylocarpa and Pterocarpus macrocarpus.

By the end of the first day, reports claimed more than 7,000 saplings had been planted.

Kim Sobon, deputy director of the Forestry Administration’s Department of Forest Plantation and Private Forest Development, declined to comment and stated he did not have permission to respond to questions about such a sensitive topic. He confirmed his department is not currently involved at Phnom Tamao.

“Reforestation is a very broad umbrella term for the re-establishment of any kind of tree cover, it doesn’t always mean forest ecosystem restoration. If you truly want to bring back the original forest ecosystem and not just smother the land in trees, it takes time,” said Stephen Elliott, co-founder and research director at Chiang Mai University’s Forest Restoration Research Unit.

In Phnom Tamao, the rapid reforestation rate, seasonal timing, tree species diversity, number of saplings planted and the distances between them all defy his nearly 30 years of experience restoring forests in the region.

Half the saplings will be dead by March, Elliott predicted.

“The most difficult thing is to get the trees through the first dry season,” said Elliott, who explained saplings need water and time to grow before the punishing dry season. August is simply too late to plant.

Phnom Tamao is a deciduous dipterocarp forest, the most widespread type in continental Southeast Asia, where up to 80 tree species can grow. Planting three species is “better than nothing” but will slow ecosystem restoration by decades. Reththy’s plan to plant 204 trees per hectare is “a drop in the ocean,” said Elliott, who recommended about 3,000 trees per hectare.

Elliott said Phnom Tamao is commercial reforestation to establish a new timber plantation: “Whoever gets the licence to log that place is going to make an absolute fortune. If the trees survive.”

Cambodia’s woodlands have become synonymous with deforestation in recent decades. The Kingdom lost nearly 22,000 square kilometres (8,494 square miles) of its tree cover, just over 20%, from 2001 to 2019, according to data from Global Forest Watch.

Environmentalists are evaluating whether the public’s role in Phnom Tamao’s conservation can be replicated to safeguard other protected areas.

Sokphea Young, a University College London research fellow who studies environmental accountability and collective action in Cambodia, said Phnom Tamao deforestation images posted online prompted “a form of visual activism that had the power to mobilise the nostalgia of forest lovers to put pressure on the responsible institutions and private sector.”

While this would be more challenging for Cambodia’s remote forests, some a half-day drive from Phnom Penh, Young believes photography and mass social media use could fuel future action.

Chandaravuth described the rapid campaign to save Phnom Tamao as a case study in the “power of people” to rescue the environment.

“In order to protect natural resources we have to come up with a creative way to make people care about the environment and the natural resources we are protecting,” Chandaravuth said. “When enough people care, the government will listen to them.”

Additional reporting by Sophanna Lay.

This article was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network. A version of this story will be available at Southeast Asia Globe and at Focus—Ready for Tomorrow, the Khmer-language publication of Globe Media Asia.