GLOUCESTER — When the self-proclaimed Prince of Whales arrived at what he calls the Nazi Fishies HQ, the rumpled scourge of all those he considers ecologically unrighteous immediately began to unload.

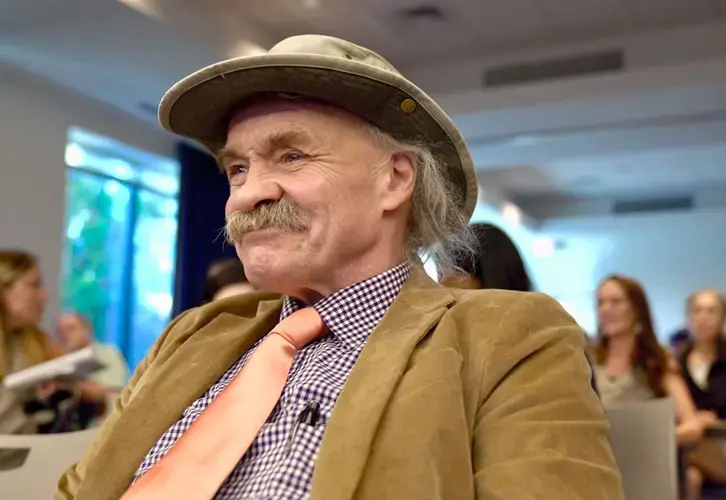

“I told the security guards there’s going to be a riot,” the Prince — Richard Maximus “Max” Strahan — said with a grin after arriving last month at the regional headquarters of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, where many familiar targets of his wrath gathered to discuss the latest controversial proposal to save North Atlantic right whales from extinction.

He lived up to his promise to stir tension, though not a riot. But it wasn’t for want of trying, for the whales have no more relentless, litigious, and truculent advocate than Strahan, nor — as even the targets of his verbal harpoons concede — one who has succeeded as much in forcing the government to protect them.

His is a monomaniacal mission to save the critically endangered species. At 68, Strahan has been at it for decades, lashing out at fishermen, scientists, bureaucrats — anyone he suspects of harming the whales — filing scores of lawsuits, engaging in civil disobedience, haranguing them with vitriolic rhetoric.

While some dismiss the man with the missing front teeth and wild gray hair as a crackpot, he has undeniably gotten results. In the 1990s, Strahan’s zeal led to a landmark victory in federal court that required Massachusetts, and eventually other states, to increase enforcement of the Endangered Species Act, earning him a grudging respect among even those he has dragged to court.

Now, with fewer than 400 right whales left, and their prospects for survival fading, Strahan is again suing Massachusetts and Maine — and many others, from scientific organizations to individual fishermen — to reduce one great risk to the iconic species: becoming entangled in the hundreds of thousands of fishing lines that interlace the Gulf of Maine.

He’s also, again, pushing for a state ballot initiative that would ban lobster lines that rise from the seafloor to surface buoys and are considered the chief threat to right whales, whose numbers have plummeted more than 20 percent since 2010.

“I’m like a green knight,” he said in an interview. “My motivations are pure; I just want to stop this species from going extinct.”

In the process, however, Strahan has alienated many who share his goals, and infuriated those who don’t.

He dismisses environmental advocates who have filed similar lawsuits to protect right whales as WINGOs (whale-interested NGOs) or charlatans. “They just live off the misery of these animals and do little more than shake down corporations for attorneys’ fees and token concessions,” he says.

Strahan calls lobstermen “rapists of the sea.” Some leading right whale scientists, he insists, are “whale frauds” who “help the fishermen avoid enforcement of the environmental laws.” NOAA officials are the “fox that got into the chicken coop.”

Over the years, the incendiary language, litigiousness, and other brash tactics have earned him rebukes from judges, exile from environmental groups, and time behind bars. Strahan has filed more lawsuits than he can count and boasts about being the “most arrested person in the history of Massachusetts,” claiming to have been detained well more than 100 times.

Most of those arrests, he says, are for trespassing, disturbing the peace, and disorderly conduct. But they also include charges of assault, illegally soliciting money, and driving a car without a license or insurance. By the 1990s, he had at least 20 criminal convictions and served time in jail. For other charges, he has received suspended sentences, fines, and community service.

He was once even banned from the New England Aquarium after allegedly behaving aggressively toward visitors boarding whale-watching cruises. Predictably, Strahan sued the aquarium in response.

Underscoring his often belligerent obstinacy, a judge in Belchertown in August placed him on pretrial probation after he admitted to sufficient facts on charges of assault with a dangerous weapon after allegedly threatening to ram a security guard at an Amherst apartment complex with his 2014 Volkswagen Jetta.

Strahan has become so maddening, or feared, that officials at some environmental and fishing groups asked that the Globe not even describe them as declining to comment, worrying that any mention of their organization might invite another lawsuit. The director of one group said Strahan has cost it more than $200,000 in legal bills over the years.

“He offends virtually all audiences — courts, scientists, enviro groups,” said Sharon Young, marine issues field director of The Humane Society of the United States, which is also suing the federal government to protect right whales.

She cringes at his tactics. “One hopes that his rantings . . . do not distract from or undermine the very real and necessary fight we and other groups are waging,” she said.

Yet Young and others acknowledge that Strahan’s exploits have made a difference.

One of his lawsuits in the 1990s forced NOAA to establish a special team of fishermen, scientists, and state and federal officials, among others, to protect right whales. Last spring, that team proposed a plan aimed at reducing the risk of right whale deaths by as much as 60 percent.

That suit also eventually led Massachusetts to ban lobster fishing for several months a year in Cape Cod Bay, when large numbers of right whales feed there.

“Max has done a lot to move the needle toward conservation,” said Scott Kraus, chief scientist of marine mammals at the New England Aquarium.

Kraus has had his share of unpleasant experiences with Strahan, and has urged him to stop “harassing” fellow scientists. He has frequently threatened to sue scientists unless they share their data. Nonetheless, Kraus said, “Max is of great value to the right whale community.”

“Because he’s out there, he forces the government and fishing community to take the radical conservation view seriously,” Kraus said. “It’s good to have someone who’s crazier than me.”

Other legal targets of Strahan also said they can’t help but appreciate his commitment to the cause, if not his methods.

“He frustrates me, because he uses up my time and is consistently off base,” said Charles “Stormy” Mayo, director of the right whale ecology program at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, which Strahan has sued again this year. “That said, he’s right in his expression of concern for right whales. We would be in a very different place without him.”

Strahan’s first cause was the northern spotted owl. He claims to have filed the first petition to list it as an endangered species in the 1980s.

A native of Western Massachusetts who now lives in New Hampshire, after sojourns on the West Coast, Strahan refuses to say much about his background or how he finances his advocacy. He has said he studied physics at Boston University and received a master’s degree in liberal studies from the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

In one recent lawsuit, he described himself as a commercial fisherman, conservation scientist, and “Plaintiff Man Against Xtinction.”

In court, where he represents himself, Strahan has often galled judges with his strident and exasperating antics.

Last spring, he asked federal Judge Indira Talwani in Boston to order state regulators to extend the closure of Cape Cod Bay to lobster fishing, arguing the state was violating the Endangered Species Act by allowing buoy lines. A recent study of right whale mortalities found that, when a cause of death could be determined over the past 15 years, the majority died as a result of entanglements.

But Strahan kept talking over Talwani, who questioned whether he was judge shopping.

When she suggested delaying the proceedings, Strahan thundered: “The right whale doesn’t have the time. . . . This court should not ignore the murder of a species.”

Unable to get in a word, Talwani eventually raised her voice.

“Please stop!” she ordered.

Months later, at a meeting in Gloucester for the public to comment on the latest proposed regulations to protect right whales, Strahan was again speaking out of turn and raising a ruckus.

To their face, he dismissed advocates from the Natural Resources Defense Council as coming to pad their “seven-figure salaries.” As a local lobsterman spoke about the potential hardship of the proposed rules, which could eliminate as many as half of the buoy lines in vast swaths of the Gulf of Maine, Strahan interrupted him.

Lobstermen in the audience appealed for security to eject him.

“Why don’t you remove vertical buoy lines from the water, instead of being cowards and criminals,” he yelled back.

When NOAA officials beseeched him to calm down, Strahan threatened to strip off his clothes, which included a satin, salmon-colored tie and a corduroy blazer.

Later, they allowed him to address the meeting as the final speaker. When he exceeded his time, he was given another minute. When he continued, a security guard and other NOAA officials surrounded him, demanding he step away from the podium.

“I’m the one that got everything happening,” he shouted. “I’m the one that Massachusetts bows to.”

He looked at the lobstermen and issued a warning.

“You’re all going to be replaced by green fishermen who . . . actually care about the environment.”

After a security officer escorted him to his seat, Strahan was still smarting.

“Kick him out!” lobstermen chanted. “Kick him out!”

Then Strahan looked at the officer and apologized, sort of, for the commotion.

“Dude,” he said, “this is about life and death.”