Steep conical hills of brown sand and stone ring the city of Lima. Massive cement water tanks cap many of the summits, some bearing a slogan of the city's powerful water utility, Sedepal: Agua Para Todo: water for all. To an inhabitant of the eastern United States, where water is generally plentiful, and where few lack a working tap, the motto appears at first to be either simply a statement of fact or an easily achievable promise. Today I learned that the slogan is neither; for hundreds of thousands, if not millions (the numbers are in dispute), of Lima's poorest inhabitants have either no running water at all or supplies that flow only a fraction of the day.

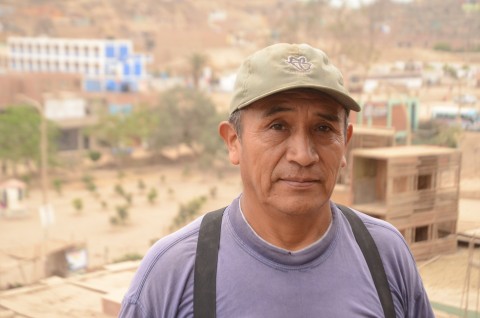

My day began early, in the San Martin district, a shantytown at Lima's northern edge. There I met Martín Mendieta, a long-time inhabitant of the Cerro Candelario neighborhood. Like many Peruvians descended from the Quechua people who were ruled by Incas before Spain conquered Peru, Mendieta is small in stature but muscular in build. He paused from a construction chore breaking rocks to chat.

When Mendieta arrived from the countryside in the mid-1970s he built a home on the stony hill where he still lives. Whether he looked to the west toward the sea or the east toward the Andes, he saw hardly anyone on the flats below his perch. The land there was either completely unused or sparsely farmed. He excavated a shallow well alongside his modest house. But the water table fell in time, and its contents became inaccessible. Meanwhile farmers and shepherds from the highlands, some fleeing communist guerillas, others drawn to the allure of city life, populated the flats with what Peruvians call "human invasions." They built sturdy brick homes at the foot of Mendieta's rampart-like hill. Now about 150,000 people live in four contiguous neighborhoods there, none of which has running water.

Mendieta says that he and his neighbors gained the stature of a community worthy of receiving city water around 1988, and they petitioned the government to hook them up. After years of petitions and protest marches, the utility Sedepal finally built a cistern for the community that looks like a giant aspirin on top of a nearby hill. But that was in 2008 and the tank is still dry. In the meantime, anyone in the area who wants water has to buy it from a truck. This morning I watched as a squadron of blue Sedepal tanker trucks careered through San Martin's uneven dirt roads, tooting horns and ringing bells to alert customers. Put one or two Soles (about 50 cents) into the outstretched hand of a truck driver's assistant and he'll fill your barrel from the end of wide hose suitable for a fire truck. Activists I consulted complained that the water is about 20 times more expensive, and far less clean, than the same thing when piped.

As I wandered through Ex Fondo Naranjal, one of the four waterless communities I visited, backhoes scraped up buckets of dirt from the roads, digging square holes for sewer connections. The activists I talked to said me that water pipes had already been installed. They said the utility promises it will pressurize the pipes later this year. Mendieta, whose house sits on an imposing rock mound, says he hasn't gotten such pipes yet. Digging trenches there is difficult, he says, giving Sedepal, his adversary for so many years, the benefit of the doubt. He's optimistic that Sedapal will fill the community's cistern soon, and after nearly 40 years even he will have running water in his home.

Next week I'll speak with glaciologists who question whether, regardless of how many people have taps, Lima will be able to keep its promise of water for all. As global warming shrinks the country's glaciers, the country might simply not have enough water on its dry western coast to match the increasing demand.