For decades, Confederate monuments have stood in front of our courthouses, watched us from our city centers and lain in our graveyards. Most of these monuments didn’t go up immediately following the Civil War, instead their time frame coincides with segregation in the South—the 1890s to 1950s—as a reminder of who was in charge.

“These monuments were also built in an effort to reinforce white supremacy at a time when Black communities were being terrorized and Black social and political mobility impeded,” writes journalist and author Clint Smith in his new book How the Word is Passed.

Across the South and far beyond, they have been powerful symbols of racism, our nation’s original sin. Now time is catching up with them.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The Southern Poverty Law Center’s 2020 "Whose Heritage?" report, which tracks public symbols of the Confederacy across the United States, found that 168 Confederate symbols were renamed or removed from public spaces in 2020. Ninety-four of those symbols were Confederate monuments.

“2020 was a transformative year for the Confederate symbols movement. Over the course of seven months, more symbols of hate were removed from public property than in the preceding four years combined,” said the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Chief of Staff Lecia Brooks.

By comparison, 58 Confederate monuments were removed between 2015 and 2019.

More than 2,100 Confederate symbols are still on display in the U.S. They include streets, parks, counties, cities, schools, military bases, and government buildings named after those associated with the Confederacy; 704 of those 2,100 symbols are monuments.

But the reckoning has begun. Fueled by episodes of police violence and institutional racism, many Americans are truly seeing these monuments for the first time, not as benign relics but as part of a campaign to dehumanize Black citizens long after the Civil War had ended. Cities, counties, churches, and universities are awakening to the bitter significance of these symbols and covering them up, tearing them down, or dismantling them entirely. Where elected officials have been slow to act, ordinary people have taken matters into their own hands.

Protestors in dozens of states have pulled down or vandalized the likenesses of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, and others who fought to enslave people. Others have been removed by local officials under the cover of night, either to protect the statue or on the grounds that it was a public nuisance.

“The Confederacy was on the wrong side of history and humanity. It sought to tear apart our nation and subjugate our fellow Americans to slavery. This is the history we should never forget and one that we should never again put on a pedestal to be revered,” said former New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu.

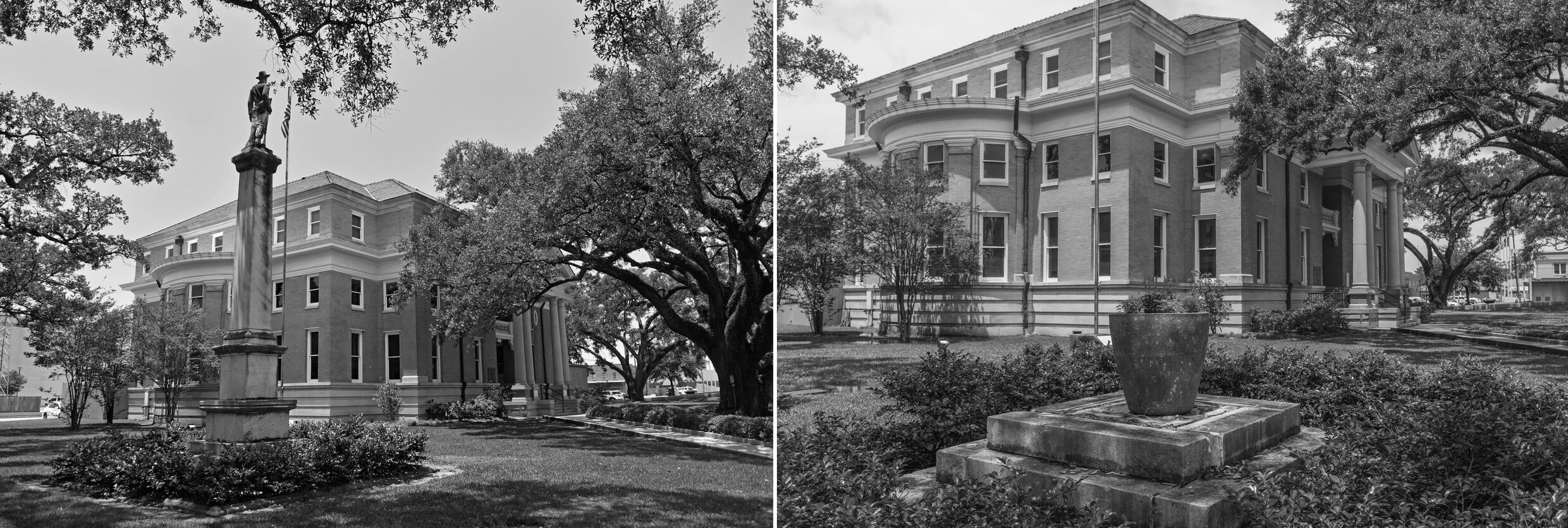

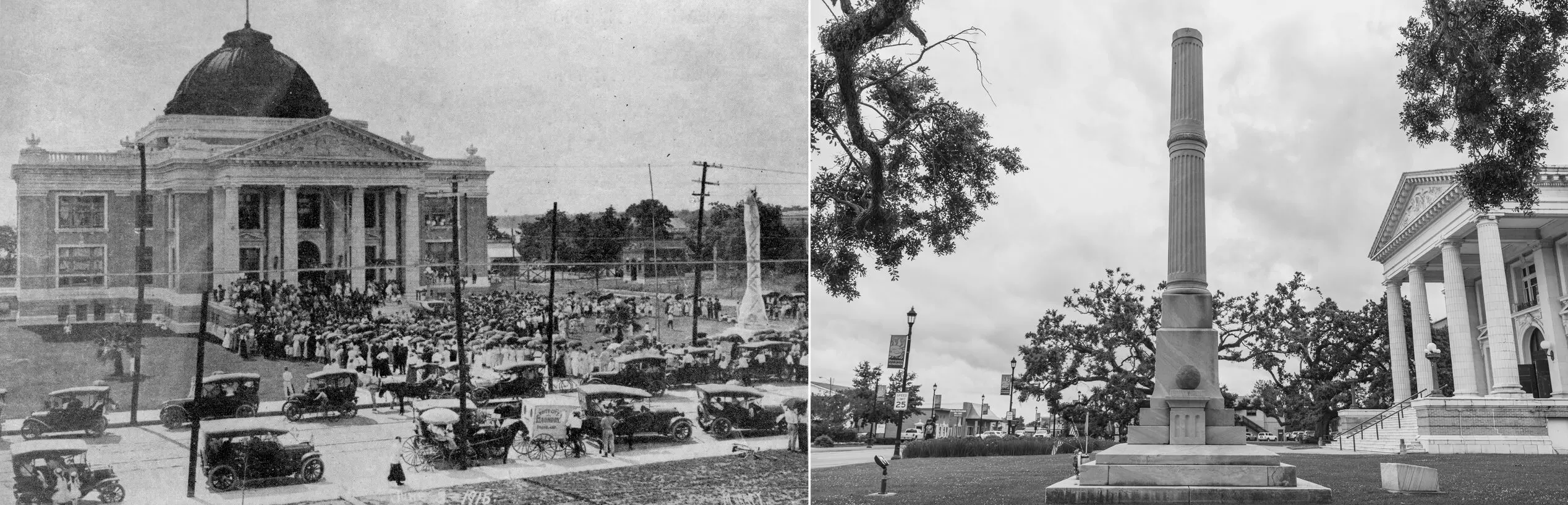

Last fall, I began to document the Confederate monuments that have been taken down since George Floyd’s death. And in April 2021, I started a 5-week, 7,300-mile road trip through the South to continue this work. My goal is to create a record of an unraveling—this moment in time when long-held narratives about Southern pride and memorialization of Civil War leaders are literally being knocked off their pedestals. I’m photographing the spaces where the monuments once stood, as well as where they’ve ended up. And I’m pairing those photos with archival images of the monuments, commemorated on postcards, and in state and university archives, or in the Library of Congress.

Some government officials were proud of their city’s actions, saying off the record that “it’s about time.” Others allowed me access to where their monument is being stored, while they wrestle with the question of what, if anything, should be done with them now.

Louisiana officials were neither proud, nor forthcoming.

In June 2020, a 12-member Iberville Parish Council voted unanimously to remove a statue of a Confederate soldier, which was erected in 1912 on the front lawn of what was then the Iberville Courthouse. It was removed about seven months later. Multiple people in Plaquemine’s parish government told me if I wanted to photograph it now in storage, I’d have to go through Iberville Parish President Mitch Ourso, who promptly hung up on me, after hearing why I was calling.

The Calcasieu Parish Police Jury voted 10-4 on August 13, 2020, to let the South’s Defenders Monument remain where it stood on the grounds of a courthouse in Lake Charles. Two weeks later, Mother Nature had other ideas, when Hurricane Laura blew through town and knocked the statue off its base, breaking it into pieces. A PIO at the Calcasieu Parish Police Jury told me that, “Unfortunately the part of the monument that came down in the hurricane is in storage and not accessible. You are welcome to photograph the pedestal which remains on the courthouse lawn.”

Jamie Angelle, Chief Communications Officer for the Lafayette Consolidated Government, told me that the statue of Alfred Mouton still remains in its original location, in front of the Old City Hall, at the intersection of Jefferson Street and Lee Avenue. Albeit, with his nose chiseled off now. “We are still waiting for the court hearing to take place but unfortunately it keeps getting postponed for one reason or another. The statue remains damaged, and we (Lafayette Consolidated Government) have no intentions to make any repairs to the statue. It will have to stay just as it is until the courts decide what to do with it."

The press secretary for the mayor of New Orleans, LaTonya Norton, emailed to say, “We respectfully decline at this time.” David Simmons, also in the mayor’s communications office, said, “Unfortunately we're not granting access at this time” and would not answer questions about whether or not their statues were still in the city lot at the “Police Car Graveyard" at Alvar and Chickasaw, as earlier news stories noted.

But, on my road trip, I saw first hand how other cities have handled this question.

Cities in Alabama and North Carolina have moved their monuments to the Confederate dead to Confederate graveyards. Cities in Georgia and Florida have moved some of their monuments out of the public eye and onto private property. Clinton, N.C., displayed their town’s statue with some context in a war exhibit in the Sampson County History Museum.

At the behest of their mayor, the Houston Museum of African American Culture was the first African American cultural asset in the country to be the recipient of a Confederate monument.

The HMAAC’s CEO, John Guess, Jr., said taking the monument in was an effort to reclaim the narrative and to “have an honest discussion about race here in Houston.”

Other cities have hidden theirs away in shipping containers, warehouses, storage sheds, public works facilities, city impound lots, a prison maintenance yard, and other “secure disclosed locations.”

And others that were vandalized or spray painted with graffiti have not been cleaned up and whitewashed.

Chris Haugh, Community Relations & Preservation Manager at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, told me he’d like to see the ones that were torn down in protest make their way to a museum someday. “It’s history,” he said. But so is the spray paint and other damage, so he didn’t clean it up or try to fix it. “That’s history too,” he said.

With that comment, Haugh captured the story I want to tell. It’s about the moment we began to reject the cruelty and white supremacy of once-revered men. And about what comes next, what’s worth preserving, and why.