Eddy Galindo’s restaurant, just steps from the beach, was empty on a warm early afternoon in December 2019. He called out half-heartedly to the handful of tourists walking by on the street, advertising rice, beans, and fried chicken.

“People don’t spend any money anymore, the economy’s bad,” Galindo said. “People spend money when they come for a week. The cruisers don’t spend any money.”

He pointed across the empty street to the ocean beyond.

“See that boat?” he said, “They’re cruisers coming back from snorkeling. Those kayaks too. They all do pre-booked tours.”

Galindo’s restaurant is on the main street of West End, a small town on the northwestern side of Roatan, the largest of Honduras’s Bay Islands. The island sits about 40 miles north of mainland Honduras in the Caribbean Sea, at the southern end of the Mesoamerican Reef, the second-largest coral reef system in the world.

Roatan, like many other destinations around the world, has been transformed by a sharp increase in cruise ship tourism, a fast-growing sector of the global tourism industry. The annual number of cruise passengers globally has risen steadily to 30 million in 2019, according to Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), with the Caribbean region making up over a third of global cruise ship deployment. Honduras received over 900,000 cruise ship passengers in the 2017-2018 cruise year, according to the most recent data published by the Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association, and the vast majority of the country’s cruise ship arrivals dock in Roatan.

While cruise tourists have provided a vital source of employment and income opportunities for islanders, many residents worry about Roatan’s future. The growth of tourism has been accompanied by environmental degradation, a growing economic dependence on visitors, and rapid demographic change. All of these changes, many residents worry, threaten Roatan’s unique culture and natural beauty that sparked the tourism boom in the first place.

The Bay Islands, in contrast to the rest of Honduras, were colonized by Britain rather than Spain, which led to a distinct culture and history from the mainland. Many local islanders are descended from the mix of Afro-Caribbean and European groups who began inhabiting the island in the early 1800s. For much of its history, Roatan was a sleepy backwater with a small population and an economy based mostly on fishing. The growth in tourism in Roatan began in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the arrival of scuba divers attracted to the world-class coral reef habitats and marine life that surround the island.

Ian Drysdale, who works as the Honduras coordinator for the Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative, an environmental non-governmental organization (NGO), described Roatan in the early days of the diving industry as “the mecca. It was really hard to get here. Beautiful reefs, you know, unspoiled. There was one dive shop and then there was three dive shops and that was it. And just, you know, word of mouth, Roatan, keep it quiet, don't tell anybody, just your friends. And then, all of a sudden, just boom: international airport, cruise ship companies.”

Cruise ships began to arrive in large numbers in the mid-2000s, with the annual number of day-visitors from cruise ships increasing 1,400 percent between 2002 and 2010, according to a study cited by the Roatan Tourism Bureau. The cruise industry dramatically expanded the potential benefits of tourism to the population of Roatan.

Synthia Solomon, the current president of the Roatan Chamber of Tourism and a former vice-minister of tourism for all of Honduras, said that before the cruise boom, “the only way the community, the local people were able to participate in tourism was working in hotels,” whereas now many islanders are able to earn a living by offering tours, providing transportation, or selling souvenirs to cruisers.

Proponents of the cruise industry point to these economic benefits for Roatan. The huge influx in the number of daily visitors has provided thousands of jobs as tour guides, taxi drivers, souvenir shop workers, and service workers at the beach resorts and restaurants that cater to the cruise ship passengers. However, cruise tourists spend less money per day than longer term visitors–primarily because they eat and sleep on the ship rather than at local restaurants and hotels–limiting the positive benefits for the local economy.

Roatan now has two cruise ship ports. One, known as the Port of Roatan, is in the island’s largest town of Coxen Hole. It is owned by a Mexican corporation and serves ships primarily from Royal Caribbean and Norwegian Cruise Lines. The other, Mahogany Bay, which opened in 2009, is owned and operated by Carnival Cruise Lines and serves ships from Carnival and their affiliated lines.

Both of these ports have expanded in the past several years to accommodate both more ships and larger ships, further increasing the number of daily cruise visitors but drawing criticism from some local residents and environmental activists.

Solomon expressed her frustration with the Port of Roatan’s dock expansion, describing the project as “the first incidence that we've had on Roatan where, in my opinion, a community has been deeply affected… I would even venture to say displaced a bit, because they are building the port right in front of their beach, you know, and it's just a mess. And it's an environmental disaster.”

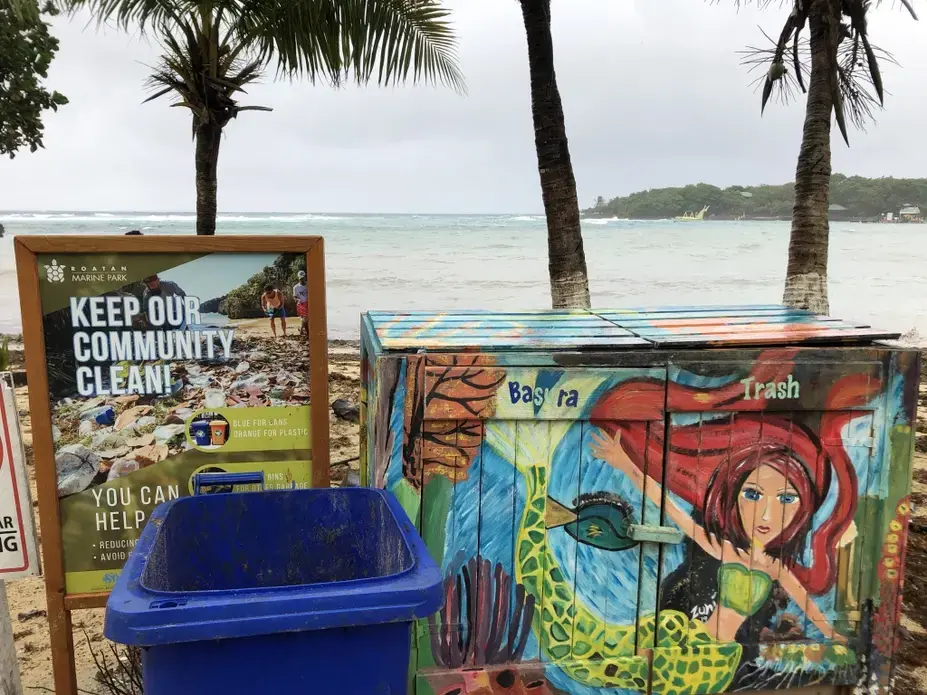

Nicholas Bach is with the Roatan Marine Park, an NGO that works to preserve the island’s coral reef ecosystems through measures including reef patrols and education campaigns. He expressed dismay at the environmental impacts of the ports, and said construction and expansion at both of the ports destroyed coral reefs that should have been protected.

Bach, whose work for the Marine Park focuses on installing marine infrastructure to limit boats from damaging the reef, described how dredging during construction and propwash from ships have harmed reefs near the ports, as well as how the new dock at the Port of Roatan has blocked currents, which could cause a once healthy bay to turn into a “stagnant pool.” Bach believes that these projects went forward over the objections of NGOs in a battle between financial benefits versus environmental considerations.

ITM Group, the Mexican corporation that now operates the Port of Roatan, did not respond to a request for comment. Elena Gonzalez-Maldonado, director of operations at Mahogany Bay Cruise Port, pointed to the port’s environmental programs as evidence that the tourism business can work hand-in-hand with sustainability efforts.

Mahogany Bay has initiated efforts including replanting mangroves on the coastal areas around the port, organizing beach cleanups in local communities, and innovating composting and recycling systems within their port. Gonzalez-Maldonado hopes that Mahogany Bay’s efforts can be replicated by other businesses across the island.

“Tourism can go hand in hand with environment,” she said. “We're not in a fight with them.”

Another criticism of the cruise ports is their consolidation of tourism’s benefits. Many cruise passengers book organized tours in advance of their arrival in Roatan, and day visitors have been increasingly drawn to the resorts of the rapidly developing West Bay area rather than other parts of the island. Additionally, both major cruise ports boast their own shopping, dining, and entertainment facilities on site, which, according to some locals, has reduced the percentage of passengers who venture out onto the rest of the island.

Elmer Bustillo, who owns a souvenir shop near the Port of Roatan in Coxen Hole that caters mostly to cruise tourists, complained that the big cruise companies are “trying to get all the whole package… they want the tourists to keep inside” the port area, diminishing foot traffic near his store outside the port gates.

While Bustillo still affirmed that tourism has been a positive economic force on the island, he has seen significant changes over the years. “The big companies they want to keep the money for themselves,” he said, shaking his head, “they don't want to share it.”

The sheer number of individuals visiting the island and the enormous boats docking daily have put an increasing strain on the island’s infrastructure. The tourist boom also has threatened the health of Roatan’s coral reef, on which the island’s prominence as a tourist destination depends.

A 2020 report by Healthy Reefs highlights the risk to reef health, citing unchecked coastal development due to tourism, and particularly the sewage runoff caused by the strain of an increased population of visitors and locals, as the biggest danger to the reef. Because of this, many residents of Roatan worry that without more sustainable tourism, the island’s lifeblood industry could collapse under its own weight.

Michele Crimmin, a hotel owner and local council member in West End, expressed her concern that current trends of mass tourism threatened livelihoods, insisting that “sustainable tourism needs to happen… because right now, the way we're headed, we won't be here.” She laughed, and clarified “I mean, not as a business. We will still be here because, well, we live here. But, you know, things will be different. Things will be very different.”

According to Solomon, the Chamber of Tourism head, a major obstacle to developing a more environmentally conscious tourism model on the island was individuals being “blinded by greed,” but she expressed hope this was changing. Solomon pointed to assessments conducted by the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) that showed significant improvement in tourism sustainability on Roatan in many categories between 2013 and 2019. She credited some of this improvement to dialogue between the NGO and business communities on the island, leading to a growing consciousness that the reef presents “natural capital” for the economy.

“People are realizing we need to take care of the ocean, because that's our livelihood,” she said, echoing a common sentiment on the island. “If we were starting development it would be much easier,” she added, “But we're already in the middle of it. Past the middle of it.”

Many activists in Roatan blame government corruption for exacerbating the negative impacts of tourism. Transparency International, a global watchdog organization, rates Honduras 146 out of 180 countries in its Corruption Perceptions Index, reflecting a high degree of public distrust in the transparency and accountability of the national government.

Drysdale, of the Healthy Reefs Initiative, described what he perceived as a culture of corruption among politicians, engineers, and businesses leading to lax enforcement of environmental regulations. In his view, which was shared by numerous other environmental activists on Roatan as well as Solomon, licenses for major commercial projects on Roatan, including the cruise ports, were granted without full consideration of the effects on local communities or fragile marine life. Drysdale also criticized perceived conflicts of interest between local officials and the tour operators who benefit most from cruise passengers.

Gisselle Brady, of the Bay Islands Conservation Association (BICA), another environmental NGO based on Roatan, also identified government policies as an impediment to sustainability in tourism. According to Brady, Honduras’s 2017 Tourism Incentive Law “undermined existing laws” that had limited beachfront development, putting the natural beauty of the island at risk as well as encouraging development without the requisite infrastructure. “It's just like the government is creating laws to take from their own people,” she said.

Gonzalez-Maldonado, of Mahogany Bay, holds a more optimistic view of Roatan’s future with tourism. Standing in the main plaza of the cruise terminal, which boasts its own private beach as well as shops and restaurants for passengers, she described the relationship between the island’s natural environment and tourism business as “positive,” but clarified that “it depends on how you want to work with it, you know?” In her view, and in the view of many residents, “[Roatan] without tourism would be a disaster” due to the island’s dependence on the sector for livelihoods.

Gonzalez-Maldonado emphasized the need for corporations and governments to show leadership in investing in sustainability and expressed optimism that things are moving in the right direction. Roatan’s municipal government recently banned single-use plastics on the island in an effort to limit the effects of plastic pollution on marine life. Multiple organizations, including Roatan Marine Park and BICA, are focusing on education campaigns to teach children about environmentally friendly practices.

Some activists worry, however, that this growing consciousness does not extend to visitors. Bach, of the Marine Park, took a pessimistic view of the cruise ship passengers in particular, lamenting that, in his view, most “don't really care about the environment, know about the environment. Some of them still think they're in Belize or Mexico.”

Manlio Martinez, a filmmaker who previously worked for a National Geographic-funded sustainable tourism initiative on the island, summed up his concern by insisting that businesses and government “need to understand that, like, all that green and all that blue needs to remain that way because that's what makes us unique. And that's what will keep attracting visitors to the island.”

There remains an inherent tension between the need to limit the environmental impacts of a runaway tourism industry and the economic dependence of many islanders on the steady stream of visitors. While Brady said her organization BICA still believes projects such as the Port of Roatan expansion had a greater impact on the ecosystem than permits allowed, she does not agree with the business interest views that NGOs ignore the economic benefits of tourism.

“It’s always ‘Oh, you don't care about the people. You just care about the environment.’” she said, characterizing this criticism. But she expressed sympathy for residents of the island who may be in favor of expanding the tourist industry further.

“Unfortunately, we're a poor country. And so, it's hard to tell someone that needs to make a living, that needs to provide food for their kids, like, ‘Hey, you know, do you know how much this really impacts us in the long run?’”

![A row of souvenir shops illuminated at night in West End] Image by Jack Shangraw. Honduras, 2019.](/sites/default/files/styles/height_500/public/photo10.jpg.webp?itok=6bkSdZPy)

Roatan’s culture and demographics have been upended by the tourist boom as well. Over the past several decades, Roatan’s population has exploded from around 25,000 in 2001 to over 60,000 in 2018, according to Honduras’s National Institute of Statistics. The island’s current population is likely much higher in part because of thousands of recent migrants living in informal settlements. Most of these people are Hondurans who have moved to Roatan from other parts of the country, seeking job opportunities and fleeing violence and crime on the mainland.

The surge in population has put further pressure on the natural environment, particularly as run-off from informal settlements without adequate sewage and sanitation infrastructure pollutes the coral reef.

Population growth has also led to tensions between mainland migrants and local islanders, many of whom regard mainlanders as being from essentially a foreign country due to their linguistic and cultural difference from the islanders. The influx of new residents combined with the economic influence of ex-patriates has put increasing strain on the island’s traditional social fabric.

Crimmin, the West End hotel owner, described how in decades past Roatan’s communities were “tight-knit,” with residents knowing each other personally and settling any disputes informally and respectfully. Now, however, she observed, “with all the tourism, with all the influence from the mainland, those communities still exist, but they're much smaller… it’s a very different place from when I was young, to where it is now.”

Aminta Tennyson, a West End souvenir shop owner with family roots in Roatan going back generations, lamented the changing economic and cultural landscape she’s witnessed since her childhood.

“All the good things of Roatan is because of the island people, not of others that is coming in.” said Tennyson. She described how foreign-owned businesses have moved onto her street, forcing her to compete with shops selling souvenirs mass-produced off the island. “It's too built up and then has so many tourists been coming in,” she complained of Roatan in recent years. “The reputation of our island, it really been going down because of that situation.”

But despite the environmental and demographic pressures, many say that cruise tourism has become too deeply entrenched in the island’s social and economic fabric to go anywhere anytime soon.

Chris (who declined to give his last name), a 34-year-old resident of Coxen Hole who gives unofficial tours to disembarking cruise passengers in exchange for tips, has been making his living from tourism since he was 10, and he has seen the changes it has brought.

“I've been working this my whole life,” said Chris, standing in a near-empty souvenir shop next door to the Port of Roatan, where an almost-3,000-passenger cruise ship from the German TUI line loomed over the town.

“Tourism is the industry that you can make a living off of. You know what I'm saying?” he said. “The tourists stop coming here man, we gonna suffer, you know? Because construction, man, [pays] about five bucks a day here on the islands. So what are we mostly doing here in the island, man? Wait for the cruise ship to come in.”

Eddy Galindo, the West End restaurant owner, sat back in his chair and looked down the street at the foreign-owned souvenir stores and dive shops that now defined his hometown. “We’ve been discovered, man. And once you’re discovered you can never go back.”

Note on the impact of COVID-19 on Roatan:

Since the reporting for this story occurred in late December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken an immense toll on the global tourism industry and the communities that rely on it for livelihoods. As of this story’s publication, all major cruise lines have halted operations, cutting off Roatan from its economic engine. Roatan Marine Park, on their Facebook page, described the lockdown as the RMP’s “hardest challenge since [the park’s] creation in 2005,” due to decreased revenues and the pressure placed on the reef by locals, most of whom usually rely on tourism income, turning to fishing to feed their families.

Michele Crimmin wrote in a text message that “the situation here right now without tourism is quite serious,” and, referencing her earlier remark that the island would be “very different” without tourism, said that “it would seem as though change came a lot quicker than expected.” Ian Drysdale, also via text, described the island as “empty.” “As I have never seen it before,” he wrote. “Ghost towns.”