Andrew Orchard lives near the northeastern coast of Tasmania, in the same ramshackle farmhouse that his great-grandparents, the first generation of his English family to be born on the Australian island, built in 1906. When I visited Orchard there, in March, he led me past stacks of cardboard boxes filled with bones, skulls, and scat, and then rooted around for a photo album, the kind you'd expect to hold family snapshots. Instead, it contained pictures of the bloody carcasses of Tasmania's native animals: a wombat with its intestines pulled out, a kangaroo missing its face. "A tiger will always eat the jowls and eyes," Orchard explained. "All the good organs." The photos were part of Orchard's arsenal of evidence against a skeptical world—proof of his fervent belief, shared with many in Tasmania, that the island's apex predator, an animal most famous for being extinct, is still alive.

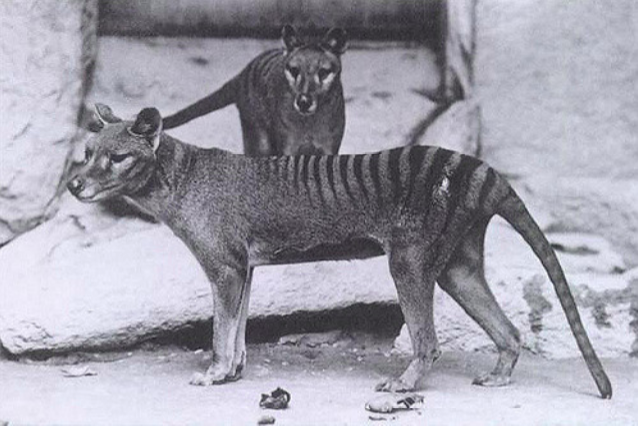

The Tasmanian tiger, known to science as the thylacine, was the only member of its genus of marsupial carnivores to live to modern times. It could grow to six feet long, if you counted its tail, which was stiff and thick at the base, a bit like a kangaroo's, and it raised its young in a pouch. When Orchard was growing up, his father would tell him stories of having snared one, on his property, many years after the last confirmed animal died, in the nineteen-thirties. Orchard says that he saw his first tiger when he was eighteen, while duck hunting, and since then so many that he's lost count. Long before the invention of digital trail cameras, Orchard was out in the bush rigging film cameras to motion sensors, hoping to get a picture of a tiger. He showed me some of the most striking images he'd collected over the decades, sometimes describing teeth and tails and stripes while pointing at what, to my eye, could very well have been shadows or stems. (Another thylacine searcher told me that finding tigers hidden in the grass in camera-trap photos is "a bit like seeing the Virgin Mary in burnt toast.") Orchard estimates that he spends five thousand dollars a year just on batteries for his trail cams. The larger costs of his fascination are harder to calculate. "That's why my wife left me," he offered at one point, while discussing the habitats tigers like best.

Tasmania, which is sometimes said to hang beneath Australia like a green jewel, shares the country's colonial history. The first English settlers arrived in 1803 and soon began spreading across the island, whose human and animal inhabitants had lived in isolation for more than ten thousand years. Conflict was almost immediate. The year that the Orchard farmhouse was built, the Tasmanian government paid out fifty-eight bounties to trappers and hunters who presented the bodies of thylacines, which were wanted for preying on the settlers' sheep. By then, the number of dead tigers, like the number of live ones, was steeply declining. In 1907, the state treasury paid out for forty-two carcasses. In 1908, it paid for seventeen. The following year, there were two, and then none the year after, or the year after that, or ever again.

By 1917, when Tasmania put a pair of tigers on its coat of arms, the real thing was rarely seen. By 1930, when a farmer named Wilf Batty shot what was later recognized as the last Tasmanian tiger killed in the wild, it was such a curiosity that people came from all over to look at the body. The last animal in captivity died of exposure in 1936, at a zoo in Hobart, Tasmania's capital, after being locked out of its shelter on a cold night. The Hobart city council noted the death at a meeting the following week, and authorized thirty pounds to fund the purchase of a replacement. The minutes of the meeting include a postscript to the demise of the species: two months earlier, it had been "added to the list of wholly protected animals in Tasmania."

Like the dodo and the great auk, the tiger found a curious immortality as a global icon of extinction, more renowned for the tragedy of its death than for its life, about which little is known. In the words of the Tasmanian novelist Richard Flanagan, it became "a lost object of awe, one more symbol of our feckless ignorance and stupidity."

But then something unexpected happened. Long after the accepted date of extinction, Tasmanians kept reporting that they'd seen the animal. There were hundreds of officially recorded sightings, plus many more that remained unofficial, spanning decades. Tigers were said to dart across roads, hopping "like a dog with sore feet," or to follow people walking in the bush, yipping. A hotel housekeeper named Deb Flowers told me that, as a child, in the nineteen-sixties, she spent a day by the Arm River watching a whole den of striped animals with her grandfather, learning only later, in school, that they were considered extinct. In 1982, an experienced park ranger, doing surveys near the northwest coast, reported seeing a tiger in the beam of his flashlight; he even had time to count the stripes (there were twelve). "10 a.m. in the morning in broad daylight in short grass," a man remembered, describing how he and his brother startled a tiger in the nineteen-eighties while hunting rabbits. "We were just sitting there with our guns down and our mouths open." Once, two separate carloads of people, eight witnesses in all, said that they'd got a close look at a tiger so reluctant to clear the road that they eventually had to drive around it. Another man recalled the time, in 1996, when his wife came home white-faced and wide-eyed. "I've seen something I shouldn't have seen," she said.

"Did you see a murder?" he asked.

"No," she replied. "I've seen a tiger."

As reports accumulated, the state handed out a footprint-identification guide and gave wildlife officials boxes marked "Thylacine Response Kit" to keep in their work vehicles should they need to gather evidence, such as plaster casts of paw prints. Expeditions to find the rumored survivors were mounted—some by the government, some by private explorers, one by the World Wildlife Fund. They were hindered by the limits of technology, the sheer scale of the Tasmanian wilderness, and the fact that Tasmania's other major carnivore, the devil, is nature's near-perfect destroyer of evidence, known to quickly consume every bit of whatever carcasses it finds, down to the hair and the bones. Undeterred, searchers dragged slabs of ham down game trails and baited camera traps with roadkill or live chickens. They collected footprints, while debating what the footprint of a live tiger would look like, since the only examples they had were impressions made from the desiccated paws of museum specimens. They gathered scat and hair samples. They always came back without a definitive answer.

In 1983, Ted Turner commemorated a yacht race by offering a hundred-thousand-dollar reward for proof of the tiger's existence. In 2005, a magazine offered 1.25 million Australian dollars. "Like many others living in a world where mystery is an increasingly rare thing," the editor-in-chief said, "we wanted to believe." The rewards went unclaimed, but the tiger's fame grew. Nowadays, you can find the thylacine on beer cans and bottles of sparkling water; one northern town replaced its crosswalks with tiger stripes. Tasmania's standard-issue license plate features an image of a thylacine peeking through grass, above the tagline "Explore the possibilities."

With the advent of DNA testing and Google Earth and cell-phone videos, it became ever more improbable that the Tasmanian tiger was still out there, a large predator somehow surviving just beyond the edge of human knowledge. In Tasmania, the idea gradually turned into a bit of a joke: the island's very own Bigfoot, with its own zany, rivalrous fraternities of seekers and true believers. Still, Tasmanians point out that, unlike Bigfoot, the thylacine was a real animal, and it had lived, not so very long ago, on their large and rugged and still sparsely populated island. As the decades passed, the number of reports kept going up, not down.

We are many centuries removed from the cartographers who used the phrase "Hic Svnt Leones" ("Here are lions") to mark where their maps approached the unknowable, or who populated their waters with ichthyocentaurs and sea pigs because it was only sensible that the ocean would hold an aquatic animal to match every terrestrial one. We've learned quite a bit, since then, about where and with whom we live. By certain accounts, however, our planet is still full of unverified animals living in unexpected places. The yeti and the Loch Ness monster are famous; less so are the moose rumored to roam New Zealand and the black panthers that supposedly inhabit the English countryside. (The British Big Cat Society claims that there are a few thousand sightings a year.) Panther reports are also common across southern Australia.

Some of these mystery animals may be part of explicable migrations or relict populations—there are active, if marginal, debates about whether mountain lions have reappeared in Maine, and whether grizzlies have survived their elimination in Colorado—while others are said to be menagerie escapees. Australian fauna are reported abroad so often that there's a name for the phenomenon: phantom kangaroos, which have been seen from Japan to the U.K. In some places (such as Hawaii, and an island in Loch Lomond), there are actual populations of imported wallabies. Elsewhere, the kangaroo in question was nine metres tall (New Zealand, 1831) or eschewed its usual vegetarian diet to kill and eat at least one German shepherd before disappearing (Tennessee, 1934).

What are we to make of these claims? One possible explanation is that many of us are so alienated from the natural world that we're not well equipped to know what we're seeing. Eric Guiler, a biologist known for his scholarship on thylacine history, was once asked to investigate a "monster" on Tasmania's west coast, only to find a large piece of washed-up whale blubber. Mike Williams, who, with his partner, Rebecca Lang, wrote a book about the Australian big-cat phenomenon, told me that "people's observational skills are fairly low," a diplomatic way of explaining why someone can see a panther while looking at a house cat. In April, the New York Police Department responded to a 911 call about a tiger—presumably the Bengal, not the Tasmanian, kind—roaming the streets of Washington Heights. It turned out to be a large raccoon. Williams, who travels to Tasmania a few times a year to look for thylacines, described the continued sightings as "the most sane fringe phenomena."

Another explanation is that the natural world is large and complicated, and that we're still far from understanding it. (Tasmania got a lesson in this recently, when the government spent fifty million dollars to eradicate invasive foxes, a scourge of the native animals on the mainland, even though foxes were never proven to have made it to the island.) Many scientists believe that even now, in this age of environmental crisis and ever-increasing technological capability, more animals are discovered each year than go extinct, often dying off without us even realizing they lived. We have no way to define extinction—or existence—other than through the limits of our own perception. For many years, an animal was considered extinct a half century after the last confirmed sighting. The new standard, adopted in 1994, is that there should be "no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died," leaving us to debate which doubts are reasonable. Because the death of a species is not a simple narrative unfolding conveniently before human eyes, it's likely that at least some thylacines did survive beyond their official end at the Hobart Zoo, perhaps even for generations. A museum exhibit in the city now refers to the species as "functionally extinct"—no longer relevant to the ecosystem, regardless of the status of possible survivors.

Tiger enthusiasts are quick to bring up Lazarus species—animals that were considered lost but then found—which in Australia include the mountain pygmy possum (known from fossils dating from the Pleistocene and long thought to be extinct, it was found in a ski lodge in 1966); the Adelaide pygmy blue-tongue skink (rediscovered in a snake's stomach in 1992); and the bridled nailtail wallaby, which was resurrected in 1973, after a fence-builder read about its extinction in a magazine article and told researchers that he knew where some lived. In 2013, a photographer captured seventeen seconds of footage of the night parrot, whose continued existence had been rumored but unproven for almost a century. Sean Dooley, the editor of the magazine BirdLife, called the rediscovery "the bird-watching equivalent of finding Elvis flipping burgers in an outback roadhouse." The parrots have since been found from one side of the continent to the other. Is it more foolish to chase what may be a figment, or to assume that our planet has no secrets left?

Last year, three men calling themselves the Booth Richardson Tiger Team held a press conference on the eve of Threatened Species Day—which Australia commemorates on the day the Hobart Zoo thylacine died—to announce new video footage and images that they said showed the animal. They'd set up cameras after Greg Booth, a woodcutter and a former tiger nonbeliever, said that while walking in the bush two years earlier he had spotted a thylacine only three metres away, close enough to see the pouch. The videos were shot from a distance, and grainy, but right away they prompted headlines, from National Geographic to the New York Post. By the time I arrived in Tasmania, this spring, the team had gone to ground. When I reached Greg's father by phone, he told me that their lawyer had forbidden them from talking to anyone, because they were seeking a buyer for their recording.

One of Tasmania's most prominent tiger-hunting groups, the Thylacine Research Unit, or T.R.U., looked at the images and pronounced the animal a quoll, a marsupial carnivore that looks vaguely like a weasel. T.R.U., whose logo is a question mark with tiger stripes, has its own Web series and has been featured on Animal Planet. "Every other group is believers, and we're skeptics, so we're heretics," Bill Flowers, one of the group's three members, told me one day in a café in Devonport, on the northern coast. Since Flowers began investigating thylacine sightings, he has been reading about false memories, false confessions, and the psychology of perception—examples, he told me, of the way "the mind fills in gaps" that reality leaves open. He talked about the unreliability of eyewitness testimony in court cases, and pointed out that many people, after spotting a strange animal, will look it up and retroactively decide that it was a thylacine, creating what he calls a "contaminated memory."

It isn't unusual for an interest in thylacines to lead back to the psychology of the humans who see them. "Your brain will justify your investment by defending it," Nick Mooney, a Tasmanian wildlife expert, told me. I met Mooney, who is sixty-four, in his kitchen, which was filled with drying walnuts and fresh-picked apples. In 1982, he was studying raptors and other predators for the state department of wildlife when a colleague, Hans Naarding, reported that he'd seen a thylacine. The department had just been involved in the World Wildlife Fund search, which had found no hard proof but, as the official report, by the wildlife scientist Steve Smith, put it, "some cause for hope." Naarding's sighting was initially kept secret, a fact that still provides grist for conspiracy theorists. Mooney led the investigation, which took fifteen months; he tried to keep out the nosy public by saying that he was studying eagles.

The search again turned up no concrete evidence, but, from 1982 until 2009, when Mooney retired, he became the point person for tiger sightings. The department developed a special form for recording them, noting the weather, the light source, the distance away, the duration of the sighting, the altitude, and so on. Mooney also recorded his assessment of reliability. Some sightings were obvious hoaxes: a German tourist who took a picture of a historical photo; a man who said that he'd got indisputable proof but, whoops, the camera lurched out of his car and fell into a deep cave (he turned out to be trying to stop a nearby logging project); people who painted stripes on greyhounds. Mooney noticed that people who had repeat sightings also tended to prospect for gold, reflecting an inclination toward optimism that he dubbed Lasseter syndrome, for a mythical gold deposit in central Australia. One man gave Mooney a diary in which he had recorded the hundred or so tigers he believed he'd seen over the years. The first sighting was by far the most credible. Eventually, though, the man would "see sightings in piles of wood on the back lawn while everybody else was having a barbecue," Mooney said. "What we're talking about here is the path to obsession. I know people who've bankrupted themselves and their family . . . wrecked their life almost, chasing this dream."

But there were always stories that Mooney couldn't dismiss. The most compelling came from people who had little or no prior knowledge of the thylacine, and yet described, just as old-timers had, an awkward gait and a thick, stiff tail that seemed fused to the spine. There were also the separate groups of people who saw the same thing at the same time. He often had people bring him to the scene, and then would reënact the sighting with a dog, taking his own measurements to test the accuracy of people's perceptions, their judgment of distance and time.

In the media, Mooney is regularly consulted for his opinion on new sightings or the species' likelihood of survival. (Extremely low, he says.) But he won't answer the question everyone wants answered. Flowers told me, "We ponder very often, does Nick believe or does he not?" Mooney's refusal to be definitive angers those who accuse him of perpetrating a government coverup of a relict population and also those who think he's encouraging nonsense by refusing to admit a dispiriting but obvious reality. Mooney thinks these views represent a thorough misunderstanding of how much we actually know about our world. "I don't see the need to see an absolute when I don't see an absolute," he told me. "Life is far more complicated than people want it to be." In his eyes, the ongoing mystery of the thylacine isn't really about the animal at all. It's about us.

To the outside world, Tasmania has long been a place of wishful thinking. For centuries, legends circulated of a vast unknown southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita, which was often said to be a land of riches so great that, as one writer put it, "the scraps from this table would be sufficient to maintain the power, dominion, and sovereignty of Britain."

This is the dream that the explorer Abel Tasman was chasing when he sailed east from Mauritius on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, in 1642. (Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean, had become a popular stopover for Dutch sailors, who restocked their larders with a large and easily hunted bird that lived there, the dodo.) Almost seven weeks later, his crew sighted land, which they took for part of a continent, never discovering that it was an island. Onshore, they initially met no people, although they heard music in the forest and saw widely spaced notches carved into trees, which led Tasman to speculate, in his published journal, that giants lived there—a notion that may have inspired Jonathan Swift's Brobdingnagians. Tasman also wrote that a search party "saw the footing of wild Beasts having Claws like a Tyger."

A century and a half later, the first shipload of convicts and settlers arrived. They didn't know what creature—later named for the devil they feared it to be—made the screams they heard in the night. When, a few months after the establishment of a settlement at Hobart, some convicts caught sight of a large striped animal in the forest, it seemed another symbol of this strange and intimidating land. "I make no doubt but here are many wild animals which we have not seen," a chaplain wrote. They encountered creatures like the platypus, an animal so bizarre—venomous, duck-billed, beaver-tailed, with the furry body of an otter but egg-laying—that George Shaw, the author of "The Naturalist's Miscellany," believed it to be a crude hoax. From the beginning, the thylacine's common names—zebra wolf, tiger wolf, opossum-hyena, Tasmanian dingo—marked it as another chimera, too incongruous to understand on its own terms.

Three years after the colony's founding, Tasmania's surveyor-general wrote a scientific description that was read before the Linnean Society, in London: "Eyes large and full, black, with a nictant membrane, which gives the animal a savage and malicious appearance." More harsh descriptions followed, from the eighteen-thirties through the nineteen-sixties: "These animals are savage, cowardly, and treacherous"; "badly formed and ungainly and therefore very primitive"; "marsupial quadrupeds are all characterized by a low degree of intelligence"; "belongs to a race of natural born idiots"; "an unproportioned experiment of nature quite unfitted to take its place in competition with the more highly-developed forms of animal life in the world today." The thylacine was stupid and backward and also, somehow, a terrifying menace to the new society, which blamed it for killing tens of thousands of sheep—an absurd inflation—and sucking its victims' blood like a vampire.

This abuse was part of a larger prejudice against marsupials that is sometimes called placental chauvinism. The science historian Adrian Desmond wrote that "civilized Europe, for its part, was quite content to view Australia as a faunal backwater, a kind of palaeontological penal colony." As Europeans spread throughout Australia, killing native animals and displacing them with their preferred species, their assessments of marsupials were as unflattering as their racist dismissals of the people they were also killing and displacing.

Aboriginal Tasmanians, who had lived on the land for roughly thirty-five thousand years, were dying in large numbers, succumbing to new diseases introduced from Europe and attacks by colonists who wanted to raise livestock on the open land where they, and the thylacine, hunted. In 1830, just twenty-seven years after colonization, Tasmania's lieutenant-governor called on the military, and every able-bodied male, to join a human chain that would stretch across the settled areas of the island and sweep the native people into exile. The operation, which used up more than half the colony's annual budget, became known as the Black Line, for the people it targeted. That same year, a wool venture in the northwest offered the first bounties for dead thylacines, and the government of the island began offering them for living Aboriginal people—later to be amended to include the dead as well.

By 1869, it was believed that only two Aboriginal Tasmanians, a man named William Lanne, known as King Billy, and a woman named Truganini, survived. Scientists suddenly became obsessed with these "last" individuals. After Lanne died, a Hobart physician named William Crowther stole his skull and replaced it with one that he took from a white body. Lanne's feet and hands were also removed; the historian Lyndall Ryan contends that other parts of his body, as well as a tobacco pouch made from his skin, ended up in the possession of other Hobart residents. There was a public outcry at the "unseemly" acts, but Crowther was soon elected to the legislature and later served as Tasmania's premier.

In 1871, two years after Lanne's death, the curator of the Australian Museum, in Sydney, wrote to his counterparts in Tasmania with a warning: "Let us therefore advise our friends to gather their specimens in time, or it may come to pass when the last Thylacine dies the scientific men across Bass's Straits will contest as fiercely for its body as they did for that last aboriginal man not long ago." Truganini, who died in 1876, professed her fear of a similar fate. Thanks to a guard who kept watch over her body, she was successfully buried. Eventually, however, her bones were exhumed and displayed at the Tasmanian Museum, along with taxidermied thylacines.

In fact, Lanne and Truganini were not the last Aboriginal Tasmanians. Descendants of the island's first people lived on, mostly on the islands of the northern coast, where Aboriginal women had had children with white sealers; today, though the numbers are contested, some twenty-three thousand people in Tasmania identify as Aboriginal. For decades, they had to fight against the widespread belief that they no longer existed. "It is still much easier for white Tasmanians to regard Tasmanian Aborigines as a dead people rather than confront the problems of an existing community of Aborigines who are victims of a conscious policy of genocide," Ryan has written. In 2016, the Tasmanian government, by constitutional amendment, recognized Aboriginal Tasmanians as the original owners of the island and its waters. As of this writing, the Encyclopædia Britannica defines them as extinct.

The politics and the emotions may have changed, but the thylacine still serves as a proxy for other debates. In March, in the tiny town of Pipers Brook, a group of Tasmanian landowners gathered over tea and quartered sandwiches to learn about how to support native animals on their properties. During the past two hundred years, more mammals have gone extinct in Australia than anywhere else in the world; Tasmania, once connected to the continent by a land bridge, has served as a last refuge for animals that are already extinct or endangered on the mainland. In Pipers Brook, the group was shown a picture of a thylacine, accompanied by an acknowledgment of grim responsibility. "A lot of what we do has the soul of the thylacine behind it," David Pemberton, the program manager of the state's Save the Tasmanian Devil Program, said. The devil, Tasmania's other iconic species, is suffering from a contagious and fatal facial cancer that essentially clones itself when the devils bite one another's faces. Pemberton has calculated that the combined weight of the tumors, most of which are genetically a single organism, now exceeds that of a blue whale.

As the group toured an enclosure for a devil-breeding program, a man named John W. Harders told me that the possibility of the thylacine's survival had become a matter of pure belief, like whether there is life after death. Other participants said that they couldn't help but feel some optimism, despite their rational doubt. "There's so much despair in terms of conservation these days," a botanist named Nicky Meeson said. "It would provide that little bit of hope that nature is resilient, that it could come back."

But some people erupted in frustration at the mention of the tiger. "We killed them off a hundred years ago and now, belatedly, we're proud of the thylacine!" Anna Povey, who works in land conservation, nearly shouted. She wanted to know why the government fetishizes the tiger's image when other animals, such as the eastern quoll—cute, fluffy, definitely alive, and definitely endangered—could still make use of the attention. I couldn't help thinking of all the purported thylacine videos that are dismissed as "just" a quoll. "It does piss us off!" Povey said. "It's about time to appreciate the things we have, Australia, my God! We still treat this place as if it was the time of the thylacines—as if it was a frontier and we can carry on taking over."

In the nineteen-seventies, Bob Brown, later a leader of the Australian Greens, a political party, spent two years as a member of a thylacine search team. He told me that although he'd like to think the fascination with thylacines is motivated by remorse and a desire for restitution, people's guilt doesn't seem to be reflected in the policies that they actually support. Logging and mining are major industries in Tasmania, and land clearing is rampant; even the forest where Naarding saw his tiger is gone. Throughout Australia, the dire extinction rate is expected to worsen. It is a problem of the human psyche, Brown said, that we seem to get interested in animals only as they slide toward oblivion.

While living Aboriginal Tasmanians were conveniently forgotten, the thylacine underwent an opposite, if equally opportune, transformation. To people convinced of its survival, the animal once derided as clumsy and primitive became almost supernaturally elusive, with heightened senses that allow it to avoid detection. "This is one hell of an animal," Col Bailey, who is writing his fourth book about the thylacine, and claims to have seen one in 1995, told me. He has a simple explanation for why the tiger hasn't been found: "Because it doesn't want to be."

Last year, the thylacine's genome was successfully sequenced from a tiny, wrinkled joey, preserved in alcohol for decades. It was a breakthrough in a long-standing project to revive the species through cloning, an ecological do-over that has been suggested for species from the white rhino to the woolly mammoth. Some critics consider cloning another act of denial in a long line of them—denying even the finality of extinction.

Of all the disagreements among tiger seekers, the most contentious is this: Do they, could they possibly, still live on the Australian mainland? Although thylacines are now synonymous with Tasmania, they lived as far north as New Guinea, and were once found all across Australia. Carbon dating suggests that they have been extinct on the mainland for around three thousand years. That would be a very long time for a large animal to live without leaving definitive traces of its existence. And yet some Aboriginal stories place the tiger closer to the present, and mainland believers contend that there have been many more sightings—by one count, around five thousand—reported on the mainland than in Tasmania.

Thylacine lore in western Australia is so extensive that the animal has its own local name, the Nannup tiger. A point of particular debate is the age of a thylacine carcass found in a cave on the Nullarbor Plain in 1966, so fresh that it still had an intact tongue, eyeball, and striped fur. Carbon dating indicated that it was in the cave for perhaps four thousand years, essentially mummified by the dry air, but believers argue that the dating was faulty and the animal was only recently dead.

To many Tasmanian enthusiasts, mainland sightings are a frustrating embarrassment that threatens to undermine their credibility; they can be as scathing about mainland theorists as total nonbelievers are about them. "Every time a witness on the mainland says, 'I found a tiger!,' it looks like they filmed it with a potato and it's a fox or a dog," Mike Williams, the panther researcher, told me. He pointed out that sarcoptic mange, a skin disease caused by infected mite bites, is widespread in Australian animals, and can make tails look stiff and fur look stripy.

Last year, researchers at James Cook University, in Queensland, announced that they would begin looking for the thylacine in a remote tropical region on Cape York Peninsula and elsewhere in Far North Queensland, at the northeastern tip of Australia, about as far from Tasmania as you can get and still be in the country. The search, using five hundred and eighty cameras capable of taking twenty thousand photos each, was prompted by sightings from two reputable observers, an experienced outdoorsman and a former park ranger, both of whom believed that they had spotted the animal in the nineteen-eighties but had, in the intervening years, been too embarrassed to tell anyone. "It's important for scientists to have an open mind," Sandra Abell, the lead researcher at J.C.U., told me as the hunt was beginning. "Anything's possible."

In Adelaide, I met up with Neil Waters, a professional horticulturist, who, on Facebook, started the Thylacine Awareness Group, for believers in mainland tigers. Waters, who was wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase "May the Stripes Be with You," told me that he has "a bit more faith in the human condition" than to think that so many people are all deluded or lying. "Narrow-minded approach to life, I call it," he said. He told me that he also felt a certain ecological responsibility, because his ancestors "were the first white trash to get off a ship, so we've been destroying this place for a long time." His family had been woodcutters, and, for him, becoming a horticulturist was a kind of karmic reparation.

In the dry hills outside the city, we stopped in an area called, appropriately or not, Humbug Scrub, and then picked up Mark Taylor, a musician and a thylacine enthusiast who lived nearby. A few months earlier, Taylor said, his son-in-law and grandson had seen what they described as a dog that hopped like a kangaroo, and Taylor was yearning for a sighting of his own. "It's becoming one of the bigger things in my life," he said. Anytime we were near dense brush, he would get animated, saying, "There could be a thylacine in there right now and we'd never know!" Once, just as he said this, there was movement on a distant hillside and he jumped, only to realize that it was a group of kangaroos. The world felt overripe with possibility.

Four weeks earlier, Waters had left a road-killed kangaroo next to a camera in a place where he had found a lot of mysterious scat containing bones. "Shitloads of shit!" he exulted. Now he and Taylor were going to find out what glimpses of the forest's private history the camera had recorded. As they walked, Taylor stopped to gather scat samples for a collection that he keeps in his bait freezer for DNA analysis. "My missus hates it," he said.

The kangaroo was gone, except for some rank fur and a bit of backbone. Waters retrieved the camera from the tree to which he'd strapped it. Taylor was bouncing again. "This is when we hope," he said. Back at the car, we crouched by the open trunk as Waters removed the memory card and inserted it into a laptop. We watched in beautiful clarity as a fox, and then a goshawk, and then a kookaburra fed on the slowly deflating body of the kangaroo. Waters laughed and cursed, but it was clear that no amount of disappointment would dampen his belief. "It's a fucking big country," he said. "There's a lot of needles in that haystack."

I thought of something Bill Flowers, of T.R.U., told me about the first time he set up camera traps in a Tasmanian reserve called Savage River. In terms of the island, where about half the land is protected, the reserve is relatively small. But the forested hills stretched as far as he could see. He began to consider the island not as it appears on maps—small, contained, all explored and charted—but as it would appear to an animal the size of a Labrador, looking for a place to hide. Suddenly, Tasmania seemed big indeed. "You go out and have a look and you start going from skeptic to agnostic very quickly," he said. I heard something similar from many searchers. "It's all very well and good to look at Google Earth and say, la la la, it's not possible for something to be not seen," Chris Tangey, who interviewed two hundred witnesses as part of his own search, in the late nineteen-seventies, said. "But then you go to those places . . ." He trailed off, sounding wistful.

For some people, contemplating the possibility of the thylacine's survival seems to make the world feel bigger and wilder and more unpredictable, and humans smaller and less significant. On a planet reeling from the alarming consequences of human activity, it's comforting to think that our mistakes may not be final, that nature is not wholly stripped of its capacity for surprise. "It puts us in our place a little bit," a mainland searcher named David Dickinson told me. "We're not all-knowing."

After dodos disappeared from Mauritius, in the seventeenth century, naturalists came to believe that the bird had only been a legend. There were drawings and records, sure, but where had it suddenly gone? Extinction was a new and much derided idea. Even Thomas Jefferson refused to believe in it for many years—how could the perfection of nature, of creation, allow such a thing? The evidence of departed species mounted until it was undeniable—dinosaur and mastodon bones were pretty difficult to account for—but it took longer to understand that humans, through their own actions, might be able to overwhelm the abundance of nature and wipe out whole species. That's part of why the Tasmanian tiger became famous in the first place. By the time it disappeared—right on the heels of passenger pigeons, which not long before had blocked out the sun with the immensity of their flocks—we were just beginning to confront the terrible magnitude of our destructive power.

We're still just beginning.