ON CAPE COD BAY — Moments after Michael Moore launched the drone, just off the starboard side of the Rosita, a charcoal-colored fluke thrust out of the dark chop. Seconds later, a few feet away, another smaller fluke emerged.

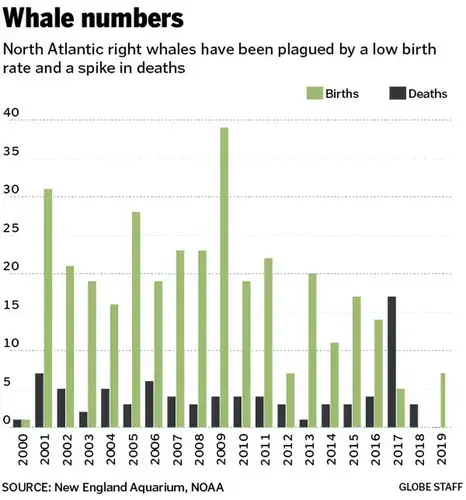

It was a rare sign of good news for the beleaguered North Atlantic right whales, among the most endangered species on the planet. There are thought to be 411 left — down from nearly 500 in 2010 — and the scientists on this recent morning had spotted a mother and her calf, one of seven born in recent months.

Toward the bow of the 55-foot sloop, Moore was staring through an enclosed viewfinder to guide his drone to just the right spot over the whales, which have experienced a spike in deaths and a sharp drop in births. He had the tricky task of flying through a fine mist showering from their blowholes, to collect vapor samples that would help his team test for bacteria to gauge the health of the whales.

“The good news is the right whales are still out there doing their thing,” said Moore, director of the Marine Mammal Center at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “They still have the potential to do what they have to do to survive as a species. We just have to let them do it.”

The whales’ arrival in Cape Cod Bay — about half of the overall population was recently there feeding on a vast swarm of zooplankton — coincides with another, more controversial effort to protect the species from extinction.

This week, a team of federal and state officials, scientists, fishermen, and others appointed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration plan to meet in Providence and issue formal recommendations that seek to reduce whale deaths and serious injuries by as much as 80 percent.

The recommendations, likely to be adopted by NOAA, could have a significant effect on lobstermen and other fishermen throughout the Northeast. The region’s lobster industry alone takes in more than $500 million a year, consistently making it the nation’s most valuable fishery.

The options being considered by the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team include closing more areas of the Gulf of Maine and nearby waters to lobster lines, which are considered a primary threat to right whales. Another change could require lobstermen to use significantly weaker rope that connects traps on the ocean floor to buoys on the surface — rope designed to break if a whale gets tangled in it.

Most fatalities of right whales appear to be the result of being entangled in fishing lines, scientists say. In a federal survey of right whale deaths between 2010 and 2014, scientists found that 82 percent died as a result of entanglements, which can drown them instantly or kill them slowly by making it exhausting to swim and impairing their ability to feed. The rest died from ship strikes.

Regulators have succeeded in reducing the death toll from ship strikes by moving shipping lanes away from areas where right whales travel and requiring large ships to reduce speeds at certain times of the year, scientists say.

But previous measures to reduce entanglements — such as requirements that lines connecting lobster traps be weighted so they sink to the seafloor or use weak links so they snap if snagged by a whale — have largely failed.

As a result, federal officials are now considering more drastic action, such as what their counterparts in Canada have done recently. Canadian officials required a host of closures after 12 right whales were found to have died in 2017, some as a result of entanglements in snow crab lines in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The regulations prevent fishermen who catch snow crabs and lobster from setting their traps when right whales are present.

NOAA now estimates that fishing lines kill or seriously injure between five and nine right whales a year. The real number is hard to know because about 60 percent of right whale deaths are unobserved, agency officials say.

In a recent letter to members of the Take Reduction Team, coordinator Colleen Coogan warned that its proposals could prove painful to fishermen.

“We know this target is daunting, but it is necessary to ensure the recovery of the North Atlantic right whale population,” she wrote.

Mike Pentony, the regional administrator of NOAA, said he hoped the team would “assist us in taking the important steps necessary to reverse the decline of this iconic species.”

Lobstermen throughout the region, however, have expressed deep concerns about the possible closures and other regulations.

In Massachusetts, lobstermen from Plymouth to Provincetown say they have borne the brunt of previous regulations and fear additional government requirements could hurt their ability to make a living.

Since 2014, NOAA has banned lobstermen from setting traps in Cape Cod Bay between Feb. 1 and April 30, or until right whales leave the area. Many of the lobstermen complain that the ban also effectively keeps them from fishing in January and May because they have to spend weeks removing and then resetting their traps.

Other closures prevent fishing in the Great South Channel, a vast bottom southeast of Chatham, between April 1 and June 30 when whales frequent those waters.

“We are looking at drastic changes coming our way,” said John Haviland, president of the South Shore Lobster Fishermen’s Association, who has spent 43 years fishing, mainly out of Marshfield.

Haviland said he has lost significant business to the existing closures.

“It causes not just economic hardship. For a lot of guys, it causes emotional or mental hardship.”

Many lobstermen feel they have been unfairly blamed for the deaths of right whales. They hope the government will find ways for them to continue fishing.

“If there are additional closures, an awful lot of guys will be hurting,” said Dave Casoni, who has fished out of Sandwich for 45 years.

Some lobstermen already lose as much as $20,000 a month because of the existing closures, he said.

While many lobstermen in Maine have benefited from record catches in recent years — the value of the landings there is now about three times what it was in 2000 — others further to the south have been struggling with more modest catches and rising costs for bait and fuel.

“For me, it’s a matter of just hanging in there,” said Casoni, 75. “But for the younger guys in the business, there’s a real question about whether they can continue making a living doing this work.”

Agency officials and scientists on the team said they recognize the threat of additional regulations to the industry.

Many of them have been hoping that new technology will ultimately enable lobstermen to fish with remotely activated devices that would raise traps to the surface.

One option the team is considering is whether some lobstermen could be permitted to use such ropeless fishing systems in closed areas, providing an incentive to experiment with the new technology.

“The situation cries for an innovative approach, and from my point of view, ropeless fishing is the best idea out there,” said Charles “Stormy” Mayo, a member of the Take Reduction Team and director of the Right Whale Ecology Program at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown.

Many lobstermen, however, say the technology remains clunky and too expensive to be a practical solution. With as many as 800 traps per lobsterman, the equipment could cost tens of thousands of dollars, they say.

While the fishermen and environmental advocates debate how to protect right whales, scientists this month have been taking advantage of their arrival in Cape Cod Bay. On a recent clear afternoon, a team aboard a Center for Coastal Studies plane counted 221 whales, distinguishing them by blotch-like calluses that form distinctive marks on their heads.

Meanwhile, on his boat in the bay, Moore flew his drone above the surfacing whales, taking pictures to measure their lengths and widths and collecting blow samples.

On another boat, Lisa Conger, a NOAA biologist, led a team of researchers taking biopsies of right whales. Using retrievable darts, they were able to collect tissue samples from the mother and calf that had recently arrived in the bay, vital information that helps scientists monitor calf survival rates.

Across the horizon, scores of whales were breaching the surface and belly flopping with a huge splash. Then they disappeared below to feed on their tiny prey.

“I’ve been doing this since the early ’90s, and it’s still awe inspiring,” Conger said. “You have to take your head out of the research for a bit and appreciate it. It’s a spectacle that never gets old.”