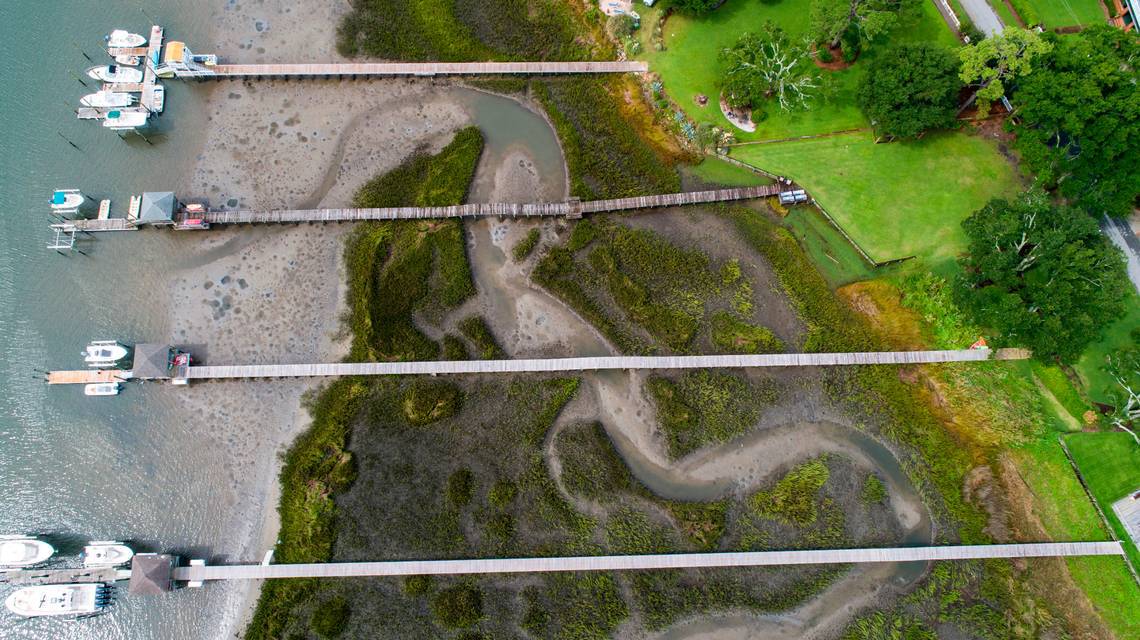

Seen from above, the salt marsh on the backside of Jekyll Island looks healthy, green, and vibrant, its spartina grass rippling in the Georgia breeze.

But a closer look reveals a nasty scar covering a section of once-thriving marsh. The federal government smothered five acres of the tideland in 2019 when it pumped black muck from a nearby dredging project onto the watery savanna.

It was part of an experiment that left some locals grumbling about an unsightly mess in a scenic wetland — and yet, the work might one day save many of the marshes that define the South Atlantic coast.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

At least that’s what scientists hope.

Rising seas are nibbling at salt marshes in the Carolinas and Georgia, threatening the tall grasses that protect the mainland from hurricane-driven waves and that sustain marine life vital to the seafood and recreational fishing industries.

So on Jekyll Island, researchers are taking steps that they think will fend off the rising ocean.

The experiment is simple: shoot enough muck onto a marsh that the muddy bottom builds up higher. With the marsh mud standing taller, rising seas won’t drown the grasses that hold these wetland systems together.

It’s a concept similar to beach renourishment, the practice of pumping sand onto eroding shorelines to widen them, which protects property and provides more room for vacationers to walk.

“We are concerned that the marshes will not increase in elevation at the same speed as sea-level rise, and that sea-level rise will eventually drown the marshes,’’ the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Clay McCoy said.

“We’re looking at what can we do, what are the impacts and can we make things better?’’

Using a pipe that vacuumed mud from Jekyll Creek, engineers pumped 5,000 cubic yards of dredged soil onto the five acres, blanketing much of the marsh with up to 10 inches of muck in the spring of 2019.

How the marsh responds to that will guide scientists and engineers interested in doing similar projects in other parts of Georgia, as well as in South Carolina and North Carolina, all of which have marshes threatened by sea-level rise.

In this case, key unanswered questions are how fast marsh grasses that were buried when mud was pumped on top of them will grow back at the higher elevation — if at all — and whether animals important to the food chain will return.

This year, scientists from the University of South Carolina, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Georgia Southern University have been monitoring the five acres of Jekyll Island salt marsh to see if there are signs of recovery since the marsh was coated with mud two years ago.

Jekyll Island, located less than 50 miles from the Florida border, is a former hunting preserve for the rich that has been developed into a major resort destination. Hordes of vacationers visit each year. The island features shopping centers, beach homes, nature centers, and towering old inns, but it also boasts expansive salt marshes like the ones scientists are studying today.

Among those who have been checking on the Jekyll Island salt marsh are Jaynie Gaskin, a Georgia Department of Natural Resources wetlands biologist who has worked on the project since it began.

During a field trip to the man-made mud flat earlier this year, Gaskin smiled as she pointed out a few sprigs of bright green spartina grass popping through the muck where dredged soil was applied most thickly.

Like other researchers, Gaskin had not seen the site in more than a year until she visited the marsh last spring.

“You can tell for sure that it has changed,’’ Gaskin said, noting the new plant growth. “This is very exciting.’’

Researchers returned to the site earlier this month, finding more extensive marsh grass growth, according to USC.

Mud helps Gulf Coast marshes

What Gaskin experienced was more than just a science project in an isolated Georgia marsh.

Hundreds of miles away, federal and state officials have for years sprayed and piped mud along the battered Gulf Coast, trying to rebuild marsh systems and barrier islands that protect cities like New Orleans from erosion and rising seas.

It’s an intense effort that dwarfs anything underway on the South Atlantic.

Gulf marshes are in many places in worse shape than those of the Carolinas and Georgia, imperiled by years of oil and gas development, changes in river patterns, sinking land, and sea-level rise.

Engineers also have pumped mud into vulnerable areas in New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and California in an effort to build up the land and save tidelands from sea-level rise.

A few marsh enhancement projects have been attempted along the South Atlantic coast, including three in North Carolina and one in Georgia.

Some of those projects have been deemed successful, including one at Freeman Creek near the Camp Lejeune Marine base in North Carolina.

Marsh grass grew thicker on land that had been built up artificially with excess mud than on the natural tideland, which was continuing to be inundated by rising seas, said Carolyn Currin, a retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist who conducted the research.

But scientists want to know more. Unlike the Jekyll Island work, the projects in North Carolina and Georgia were either tiny — like at Freeman Creek — or done in the 1970s and 1980s.

Some early marsh projects focused almost exclusively on whether the Corps of Engineers could dump mud in tidelands without causing long-term environmental damage. Unlike the Jekyll Island project, the focus wasn’t building up the land to combat rising sea levels.

At Jekyll, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers made a point not to replant marsh grasses once the mud was dumped on the healthy tideland. Instead, the Corps wanted to learn how fast marsh plants and sea creatures that live there would return, said the agency’s McCoy.

No one expects dredged mud to be pumped on every inch of salt marsh in the southeast to combat sea-level rise. That’s unrealistic. But experts say it could work in many areas where salt marshes are most in danger from the ocean.

One researcher interested in the Georgia project’s outcome is Denise Sanger, with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. She’s looking into whether South Carolina could do the same thing.

“We haven’t really done a lot of it,’’ Sanger said. “Dredge disposal on marshes was proposed years ago, largely to get rid of the material — as opposed to now, where we are looking to see if this can allow us to keep up with sea-level rise.’’

Grand Canyon of salt marshes

The need to save salt marshes is important for multiple reasons. The soggy tidelands cover more than 1 million acres in the Carolinas, Georgia and North Florida, an expanse that covers roughly the same acreage as the land at Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona.

Not only do salt marshes preserve the natural scenery that so many people know from visits to the South Atlantic coast, but they shield the mainland from hurricane-driven storm surges.

A single acre of marsh can absorb 1.5 million gallons of flood water, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, which is spearheading efforts to protect Southeastern salt marshes from sea level rise.

Tidal marshes also are vital to the fishing industry. The marsh grasses provide places where crabs, fish and shrimp grow up, feasting on the abundance of microscopic organisms that live there and hiding amongst the spartina stalks from big predators.

Salt marshes are so important that they are used by 75 percent of the fish and shellfish at some point in their lives, state and federal agencies report.

From North Carolina to the east coast of Florida, a region with some of the nation’s most expansive salt marshes, recreational fishing trips, boating and eco-tourism contribute nearly $4 billion to the economy annually. Recreational anglers, for instance, took 16.8 million fishing trips in the region in 2016.

Meanwhile, the total domestic economic impact of commercial fishing in the region exceeds $1 billion from sales, NOAA statistics show

Jim Morris, director emeritus of the Baruch Institute at the University of South Carolina, knows perhaps more about the potential loss of salt marshes than most scientists in the Southeast. He’s been studying marshes since the early 1970s, and is one of the lead researchers on the Georgia restoration experiment.

“The question is can we use dredged sediment to renourish marshes and raise their elevation and improve their survival chances?’’ Morris said. “I think the answer to that is absolutely we can.’’

Sea-level rise threatens salt marshes

South Atlantic salt marshes most threatened by rising sea levels are on the southern North Carolina coast, the Murrells Inlet, Charleston areas of South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Fla., according to resiliency maps from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Threats also exist in the Hilton Head Island-Savannah area. Areas in red and orange on this map show spots where marshes are least resilient to sea-level rise. Areas in green are most resilient. Source: NOAA

Hope for Jekyll Island marsh

Not everybody thinks the effort is a solution to rising sea levels.

Among them is James Holland, a former Altamaha riverkeeper.

Holland took aerial photos of the Jekyll Island marsh after hearing about the project. He didn’t like what he saw.

In an interview with The State newspaper, Holland said he believes the Corps is simply “looking for a place to dump their garbage,’’ referring to the excavated mud from dredging projects. He said the damage done to the environment is a big concern.

“Pumping all that mud out there, with any of the critters that were out there, hell, they killed them,’’ he said. “I said to myself there ain’t no way in hell this is going to work.’’

Others say that building up salt marshes, while an admirable effort, is not the long-term answer to rising sea levels. Salt marshes need the ability to slowly move inland as sea levels rise, a natural process, scientists say.

“All of this is great, but it’s a tiny, tiny solution to a really big problem,’’ said Rob Young, a Western Carolina University coastal geologist. “Holding these marshes in place as sea level continues to rise is a losing battle.’’

Morris said he’s heard the criticism before, particularly complaints about aesthetics.

“It’s not terribly popular with laypeople, locals, because the marsh ends up looking like a moonscape’’ until it recovers, Morris said. “But when they recover, they look great.’’

On a brilliant warm day earlier this year, those working with Morris on the Jekyll Island project boarded a boat at the Georgia DNR’s Brunswick office and cruised a few miles down the Brunswick River to the project site in the marsh along Jekyll Creek.

After landing on a small beach adjacent to the marsh, they trekked through waist-high spartina grass to the barren moonscape Morris described.

Mud covered most of a circular area a few hundred yards from Jekyll Creek, a part of the Intracoastal Waterway. The mud was so gooey in places that scientists had to step carefully to avoid getting stuck.

Researchers spent the day taking soil samples, measuring the height of spartina plants and looking to see if crabs, mussels, snails and other marsh animals were returning to the mucky flat.

Gaskin and Karen Sundberg, a researcher who works with Morris at USC’s Baruch lab, pulled up cores of marsh mud for analysis later. Their boots and gloves were caked in the dark, wet sediment.

One of the questions is whether the dredged soil engineers dumped on the marsh begins to take on the same characteristics as the natural muck below it.

That would help foster the regrowth of spartina grass, a willowy plant that holds salt marshes in place with its extensive root system. Spartina grass is the most dominant plant found in low-lying salt marshes.

At Jekyll Island, two of six plots Georgia Southern University was monitoring earlier this year showed “a fair amount of growth,’’ said Risa Cohen, a GSU scientist.

Cohen said research Georgia Southern is conducting will guide state and federal agencies on future marsh protection projects.

“You don’t want to tell somebody to go dump a bunch of dredged (mud) on top of the marsh and it’s going to be amazing, if you don’t have data to back it up,’’ Cohen said. “These projects have a real importance in setting some of the ideas about what sorts of techniques and policies to use. I’m thrilled to be a part of that.’’

Cohen, who formerly studied marshes in California, said she hopes the Georgia experiment will be a success. Unlike some parts of the country, southeastern wetlands are still vibrant enough to be saved, she said.

“One of the reasons I came here is I wanted to be somewhere where I could still make a difference,’’ Cohen said.

How salt marshes survive

When salt marshes are threatened by sea-level rise, they have two survival strategies.

One is by increasing their elevation by trapping sediment or using below-ground biomass.

Another way is to move upland as sea level rises and salt water moves inland. The problem comes when bulkheads and other hard surfaces get in the way.