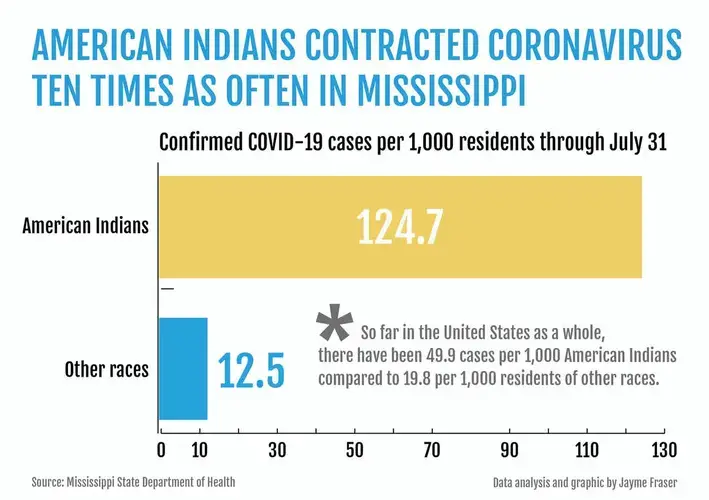

The coronavirus pandemic has hit the Mississippi Choctaw Band of Indians harder than any major city in the nation — and 10 times harder than the rest of Mississippi.

Of the 10,000 Choctaws served by the tribe, one in 10 — 1,092 — have tested positive for COVID-19.

“That’s worse than what we’re seeing in New York City or anywhere else in the U.S.,” said the 42-year-old Chief Cyrus Ben, who has battled the disease himself, suffering fever and chills.

By comparison, one in 34 residents in New York City has tested positive.

Neshoba County, where much of the tribe lives, has the highest death rate per capita in Mississippi and one of the highest in the nation. Among the Choctaws, 78 have died, or 1 out of 128 — more than twice as many per capita as New York City.

Within days of graduating high school, one Choctaw student saw the coronavirus steal the lives of both his mother and father.

“Bryce Thomas should be celebrating his recent graduation from Neshoba Central High School with his parents,” family friend Raymond Reynolds wrote for a GoFundMe page to support Thomas. “Instead he is having to bury both of his parents due to the coronavirus. What should have been a time of joy and celebration has now turned into a tragedy no young man should have to face.”

Among Native American tribes, Mississippi Choctaws have one of the highest infection rates in the nation, said Lynn Malerba, chairwoman of the Mohegan Tribe and tribal governance advisory committee.

While COVID-19 has disproportionately affected black, Latino and other populations of color, it has proven more deadly to some Native American tribes than any other group. A new report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the infection rate for Native Americans three and a half times higher than for white Americans.

Although the Choctaws represent less than 18 percent of Neshoba County’s population, they account for more than half the cases and nearly two-thirds of the deaths. More members of this small tribe have died from COVID than the total coronavirus-related deaths in Hawaii, Alaska or Wyoming.

Native Americans suffer from diabetes at a higher rate than other races. That’s one reason experts cite for why Native Americans may be at higher risk for death or severe complications from the coronavirus.

‘The mission of this agency was to stop the Choctaw from dying’

In his first year as Choctaw chief, Ben has spent much of his time handling emergencies. Storms hit, causing serious power outages, and a tornado ripped through the center of the Bok Homa community in Jones County last year. Then came February’s floods, followed by the pandemic.

Battling a pandemic is new to this generation, but nothing new to the tribe. When Europeans arrived in North America hundreds of years ago, there were more than 5 million Native Americans on the continent.

In addition to their dreams of conquest, Europeans brought diseases, which killed many Native Americans because they lacked immunities. By the 1900s, their numbers had shrunk below 238,000.

Katherine M.B. Osburn, an associate professor of history at Arizona State University and author of Choctaw Resurgence in Mississippi: Race, Class, and Nation Building in the Jim Crow South, 1830-1977, wrote that the 1918 influenza pandemic was devastating on the Mississippi Choctaw. U.S Census data reflects that 20 percent of the population may have been wiped out.

The immense loss of life led to the creation of the Choctaw Agency in 1918, she told the Mississippi Center For Investigative Reporting. “The mission of this agency was to stop the Choctaw from dying, so there is a connection between these two pandemics.”

Chief Ben said the big challenge is that Choctaws are “a very social people and tight-knit. And now, out of the blue, we’re being told that we cannot be social. That’s quite a challenge.”

In the tribe, there have been more infections among those between 21 and 30 years of age than any other age group.

They, in turn, are spreading the coronavirus to others, Ben said. Neshoba County and the Choctaw reservation’s high death rates have devastated the tribe’s elderly population, according to Mary Harrison, interim health director of the Choctaw Health Center.

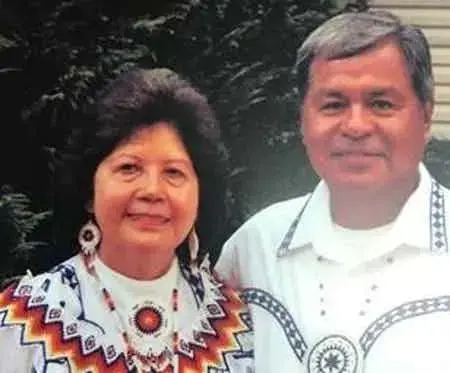

Harrison has seen COVID kill three in-laws: her children's grandmother, grandfather and great-grandmother. Lena Denson, the “glue” of her family, was the former first lady of the Choctaw Nation and a strong voice for traditional beliefs and ways of life. Lucy Morris, her children’s great-grandmother, was a respected seamstress and traditional cook. The grandfather, Benson Lewis, like the two women, spoke the Choctaw language fluently.

Harrison decried the death of such “family treasures. Our culture within our family has been lost.”

COVID has also killed younger tribal members and halted traditional tribal practices through gatherings, she said. “We're losing parts of our culture here, losing parts of who we are and how we connect with our identity as tribal members.”

This devastation, she said, “ignites something in me to help take care of my tribal people.”

Mitzi Reed, a wildlife conservation officer who lives in the Pearl River community, saw her uncle and grandmother die days apart in May.

But she said she wasn’t able to attend either funeral because she and her sister care for their mother, a dialysis patient. “It was just too risky.”

When her mother goes to dialysis, she wears a mask and fishing garters, Reed said. “Once she comes home, it’s 30 minutes of disinfection. We just want to make sure.”

The last thing that Rita Mattera of the Pearl River community expected when the pandemic hit was burying her 47-year-old daughter, Sheila Rivera.

Rivera was working as a corrections officer in Chicago for the detention center at the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, where she was asked to watch inmates with COVID.

“She told them she was diabetic, but that didn’t mean anything to them,” Mattera said.

Her daughter worked the first 10 days without masks, gloves and the like, catching the disease from inmates. On April 19, she suffered a seizure and died, and a funeral procession will start Sep. 25 at the Choctaw Police Department, where she once worked, Mattera said. “It has devastated me.”

‘Our people have come through a lot’

Under Choctaw tradition, a person’s spirit is believed to remain for several days before journeying to the “Land of Ghosts.” In keeping with that tradition, a family holds a three-day wake in the home, with the community coming together to support the grieving family, tribal members say.

That has been impossible in the days of COVID, said social worker Sally Allen. “It was a difficult time and still is.”

In June, her brother-in-law died, and her son-in-law and his grandmother died within an hour of each other at the hospital, she said. “One co-worker lost her sister. Another lost her aunt and two cousins. Our clients are elderly clients, and some of them have passed on.”

In the wake of the pandemic, funeral home director John Stephens of Philadelphia has held double funerals for the same families, including a husband and wife and two sisters.

“No one has ever seen anything like that before,” he said, “nothing like this since the Spanish flu or the bubonic plague.”

Father Bob Goodyear, who has pastored the Holy Rosary Indian Mission in the Tucker community and two other Choctaw churches for nearly three decades, has witnessed the tribe’s transformation, going from dirt roads to asphalt thoroughfares, from clapboard houses to casinos, which reopened Aug. 28.

But he’s never seen anything like COVID-19. Because almost everyone on the reservation is related, the disease is “touching everybody,” he said.

The cemetery for his church, the place where many Choctaws are buried, is so packed with people, it has little room left.

Tribal officials say a Choctaw community cemetery is in the “planning stages” to take pressure off the Holy Rosary cemetery.

The pandemic has become personal for Goodyear, who is now battling COVID-19’s famous fever, chills and weakness. “I feel like the poster child for all the symptoms,” he said.

Melford Farve, who writes for the Choctaw Community News, said Choctaws were “caught off guard, like a lot of America.”

These days, “I see more Choctaws wearing their masks,” he said. “People are taking it a lot more seriously.”

The Choctaws are “a resilient people, and we will overcome, just like we have overcome the government trying to assimilate us and knock down our culture,” he said. “Our people have come through a lot, and that’s how we’re going to have to face it. We will get to where we need to be.”

Jayme Fraser and Kristine de Leon contributed to this report.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

The Poverty & the Pandemic is a continuing series from the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and the Pulitzer Center that captures the stories of people and places hit hardest by the nation's worst pandemic in a century. If you would like to continue receiving these stories, please sign up for our newsletter.

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR's newsletters here.

Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.