TCHULA — This small town sits an hour from the suburbs of Mississippi’s capital city of Jackson, but it rests a world away.

It is the poorest town in the nation’s poorest county, the most forgotten place in America.

“We were already off the cliff with no safety net,” said Holmes County Supervisor Leroy Johnson. “Then COVID came.”

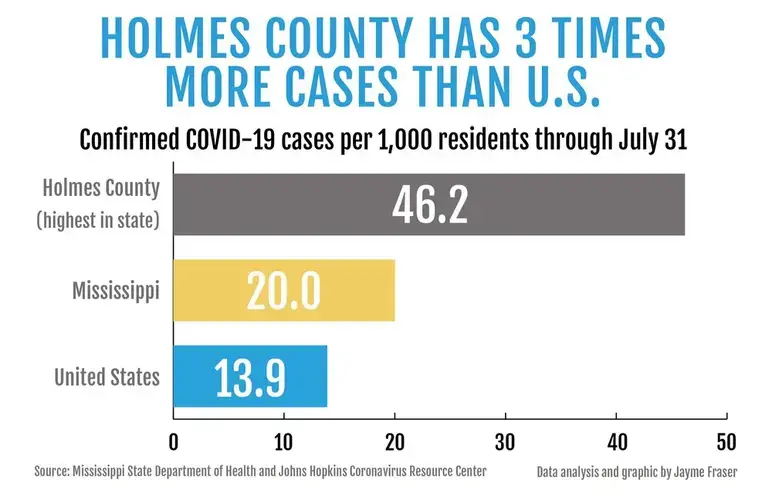

People in Holmes County have contracted the coronavirus twice as often as residents of Hinds County — and died from the disease seven times as often. The rate of infection in Holmes County is more than three times the national average.

At the 80-bed Holmes County Long-Term Care Center in Durant, most of the staff members and residents came down with COVID.

One of those residents, 80-year-old Lula Pearl “Duley” Benford, was already suffering from diabetes, resulting in the amputation of one of her legs.

At 4 a.m. May 25, her daughter, Annie Lee Benford, received a call from a nurse at the center who said the ambulance was coming for her mother.

The same nurse called back with the news that employees had tried to resuscitate her mother, but she had died.

Benford said her sister, who was also at the home, became ill as well and had to go on a ventilator.

In further conversations with staff, Benford said she learned that a nurse employed by the center became ill at work.

Each time MCIR contacted nursing home officials for comment, asking how they were keeping residents safe, they hung up the telephone.

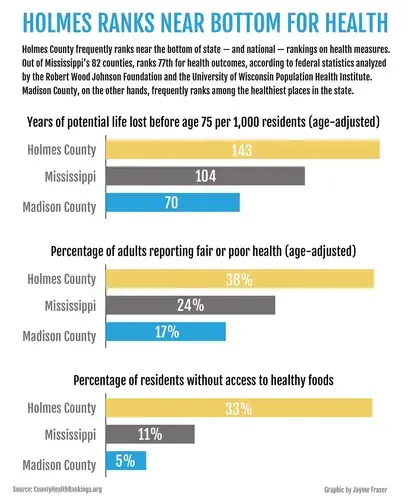

Johnson said what has made Holmes so vulnerable has been the number of people suffering from underlying health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and lung disease.

Diabetes here runs more than twice as high as the national average. Many more suffer from prediabetes, a precursor that can lead to the devastating disease.

One reason Tchula has been hit hard is the town is “a food desert,” said Edelia Carthan, a Tougaloo College professor whose father Eddie Carthan became Tchula’s first African American mayor. “They have to drive miles, either to Lexington, Yazoo City, Jackson or Greenwood just to get fresh food.”

Calvin Head works with the Mileston Co-op, which provides jobs to young people, some with disabilities, to plant and harvest fresh vegetables to address this shortage.

When the pandemic sent children home from school, he and others stepped up to provide food boxes for those children.

The co-op has taken over an abandoned building that once housed a local school and turned it into a community development center that is helping create jobs, Head said.

Deluges have devastated the land the past two years, but the current pandemic puts such woes to shame, he said. “This is the worst there is, COVID-19. You get by with a little flood, but this stuff is serious.”

‘This Pandemic Is Real.’

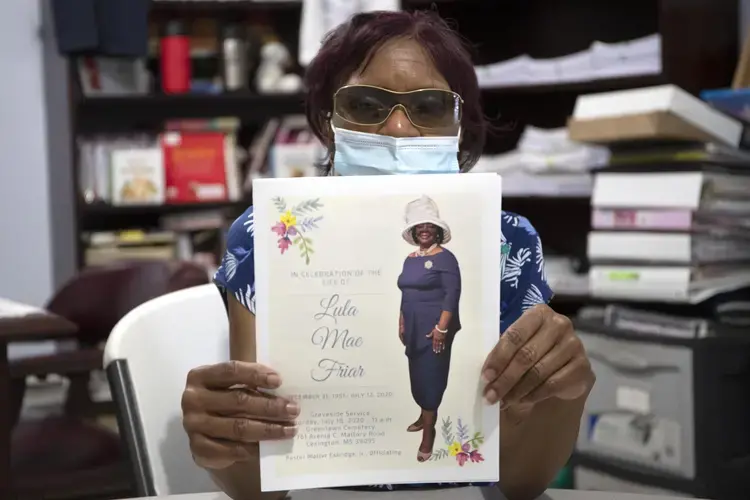

Lula Mae Friar worked as a school teacher for 34 years in Lexington.

She mentored many young people, running a program that assisted pre-K students in learning, as well as “adopting” a dozen high school seniors this past year.

At the Community Students Learning Center, she made sure students wore masks and kept the building safe through constant use of disinfectant.

“That was the kind of person she was,” said her sister, Beulah Greer, who worked as the center’s executive director. “She was a pillar of the community.”

One Friday in May, Friar told her co-workers at the center that her knees were hurting. The next day, she tested positive for COVID.

On May 30, she went to the hospital in Jackson, where she was placed on a ventilator. Six weeks later, they buried her.

“This pandemic is real,” Greer said. “Somebody close to you can get infected.”

She has a 6-year-old granddaughter and worries she might catch COVID from her.

“Right now, we’re very vulnerable,” she said. “We need to do our best to take care of each other so that we don’t spread it to someone else.”

‘We’re A Broadband Disaster.’

Telemedicine has been touted as a replacement for face-to-face medical visits, but it remains a challenge in this area, Johnson said, because “we’re a broadband disaster. We don’t have it.”

Tchula Mayor General Vann said that’s why a crowd can be seen gathering outside the library in the evening, tapping into the public wi-fi.

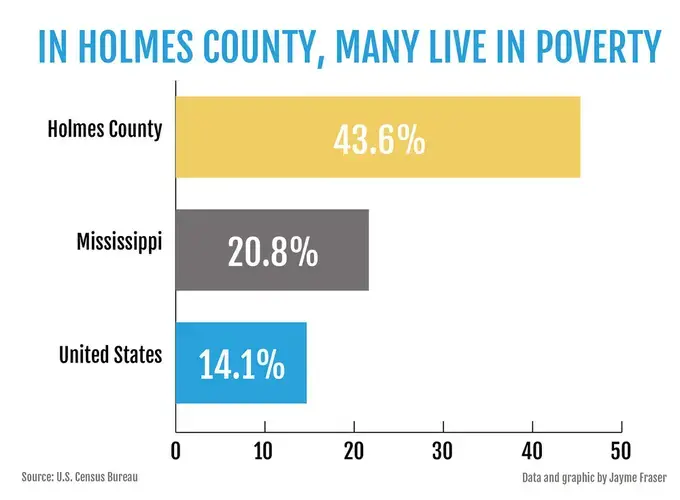

Nearly half the population here lives in poverty — more than three times higher than the national average.

Such poverty has made it difficult to test citizens for COVID, despite Holmes County making the state’s list of hotspots.

It wasn’t until July 1 that the county saw its first COVID screening in which patients didn’t have to be pre-screened through a smartphone app. That screening took place in Lexington, a dozen miles from here.

Lexington Mayor Robin McCrory noted that “even if people have a smartphone, they may not know how to download the app.”

Beyond that, “one of the biggest issues we have in small towns — even though it’s the age of computers — is getting the right information out to the public,” she said.

Some information confused the public, she said. “We were already back to business when all of a sudden we were put on the hotspot list.”

‘She Died In Front Of Her Kids.’

Because of poverty, a lot of families have to live together here in small spaces. A half dozen vehicles or more can be seen outside some trailers.

And their workplaces in nearby counties are often packed tight, making it impossible to quarantine, said local resident Francine Jefferson.

Clara Kincaid was one of those. The 50-year-old supervisor at Peco Foods chicken plant in Canton worked there for more than two decades, said Jefferson, who was her sister-in-law.

The plant initially didn’t have masks and gloves for workers, she said.

In March, Kincaid began complaining that a number of sick employees continued to work, Jefferson recalled. “She said, ‘I think they’ve got the virus.’”

In early April, the single mother of four and the grandmother of six discovered she was ill, no longer able to speak without coughing, Jefferson said.

Kincaid, who was still caring for two of her sons, initially hesitated to get tested, she said. “She didn’t want to get taken away from her kids.”

On April 14, Kincaid drove more than 40 minutes to a MEA Medical Clinic in Canton, where doctors diagnosed her with COVID-19.

Two days later, she woke up and told her youngest son, “I’m so tired,” before collapsing on the floor, Jefferson said. “She died in front of her kids.”

What she can’t understand is why the doctor sent Kincaid home, instead of sending her to the hospital since she was already suffering from pneumonia and a fever.

“They sent her back home to die,” she said.

Clinic officials told MCIR that when a patient tests positive for COVID, that patient is told to isolate and if symptoms grow worse, to head for the nearest emergency room.

The clinic didn’t send home a brochure, Jefferson said. “We were trying to guess and figure it out.”

Kincaid was a beloved figure in the community, helping many people get jobs at the plant and helping her family as well, she said. “She was the one we all depended on. It’s heartbreaking not to have her. It’s such a void in our lives.

“Her death is so senseless. It didn’t have to happen.”

Peco officials responded that team member safety has always been part of the company’s core values and that masks and other safety measures have been required since before the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued safety protocols that included masks.

Company officials said in a July 15 email to MCIR that they are taking temperatures of anyone coming into facilities and screening them. They say they are disinfecting the plant and have installed partitions at work stations.

Officials for Peco, which had COVID outbreaks among its Mississippi poultry workers, said the state Department of Health “has assured us that the plants are exceeding the federal and state guidelines for protecting essential workers.”

Liz Sharlot, spokeswoman for the department, said Aug. 24 that State Epidemiologist Dr. Paul Byers does not recall making that remark.

Richest Soil, Poorest People

The western part of Holmes County belongs to the Mississippi Delta, a place with some of the world’s richest soil and some of the nation’s poorest people.

By World War II, mechanical cotton pickers began to replace the work done by hand, helping fuel the Great Migration that led many African-American families north.

Those who stayed behind struggled.

Today, the per capita income in Holmes County is less than $14,000. Nearby Madison County has a per capita income nearly three times higher, $38,496.

The lack of decent jobs has led to a massive brain drain, said William Dean Jr., who in 1974 became the first African American elected superintendent of schools in Holmes County.

“We just don’t have any industry here,” he said. “If people finish school, they just leave.”

Despite such poverty, the county has played a key role in Mississippi history.

A lawsuit here led to the U.S. Supreme Court ordering implementation of Brown v. Board of Education in 1970, and Robert Clark became the first African American elected to the Mississippi House since Reconstruction.

And on July 2, Holmes County made history again by purchasing and delivering masks to every single resident, along with some hand sanitizer. The new masks can be washed up to 15 times.

Johnson said he felt driven to push for this as a supervisor, wanting to make a difference in health care in his native county.

He remembers back in 1963 when his aunt died after her appendix burst. “The hospital wouldn’t take her because of the color of her skin,” he said.

What happened with her inspired his brother to become a medical doctor, he said. “He didn’t want another Aunt Katherine to die because of the color of her skin.”

COVID-19 first spread into this area after those attending a March 26 funeral at a Church of God in Christ in Clarksdale returned to Holmes County, where the 6 million-member denomination began more than 120 years ago.

Hundreds were exposed to the disease at the funeral, and many became ill, said Dean, the superintendent of the Lexington district.

Shortly after that, Bishop T.T. Scott, who had been a pastor since 1972, drove to Atlanta to pick up his wife.

A day later, he fell ill, and his son took over the driving. He died in early April, and his son died several days later.

Since then, two pastors in the district in Lexington have died, Dean said. “One was chairman of my district. He pastored two churches in my district. One was a pastor at Pickens. He was the first black mayor of Lexington.”

Those pastors were “close and supportive of me,” he said. “You miss them and hate they’re gone.”

In the Lexington district alone, the church has lost about a dozen members, and nationally that number tops 30, he said.

Funeral services play an important role in the African American community, but Johnson said COVID’s spread “opened everyone’s eyes that the things that were customary to do were the things that were killing us,” he said.

Without traditional funerals, people can’t process their grief, he said. “Folks are still mourning here. They’re still going through grief.”

All of this has dragged the community into an abyss, he said. “I don’t know how we’ll get out of it easily.”

The community remains strong, “but they haven’t seen this kind of devastation for a long time,” he said. “You see the light go out of people’s eyes, the light is dimming, and I don’t know what we can do as a community and as a government to relight the light in folks’ eyes because cases are going up and we’re continuing to have among the highest per capita.”

Jayme Fraser, Kristine de Leon, Sarah Fowler, James Finn and Samuel Boudreau contributed to this report.

The Poverty & the Pandemic is a continuing series from the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and the Pulitzer Center that captures the stories of people and places hit hardest by the nation’s worst pandemic in a century. If you would like to continue receiving these stories, please sign up for our newsletter.

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletters here.

Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.

- View this story on Clarion Ledger