As the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Milwaukee residents Estella Johnson and her husband were struggling with reduced work hours. They were also fighting an eviction order from a landlord she said doesn’t perform repairs and who changed the locks without notifying tenants.

Johnson couldn’t get into her apartment for five days and could not access her mail for more than a month because she said her landlord changed the locks without notifying tenants. When she finally got her mail, she discovered an eviction warning. “By the time I got my five-day notice from them, it was past the five days,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s landlord, Berrada Properties, is one of the leading filers of evictions in Milwaukee. The city had one of the highest eviction rates nationwide before the pandemic, with about 16 evictions every day in 2016, according to Eviction Lab data.

This year, Berrada led the way: Berrada Properties and affiliates were responsible for 16% of eviction filings in Milwaukee city and county since March 27, 2020, or 480 of the 2,929 filings during that period.

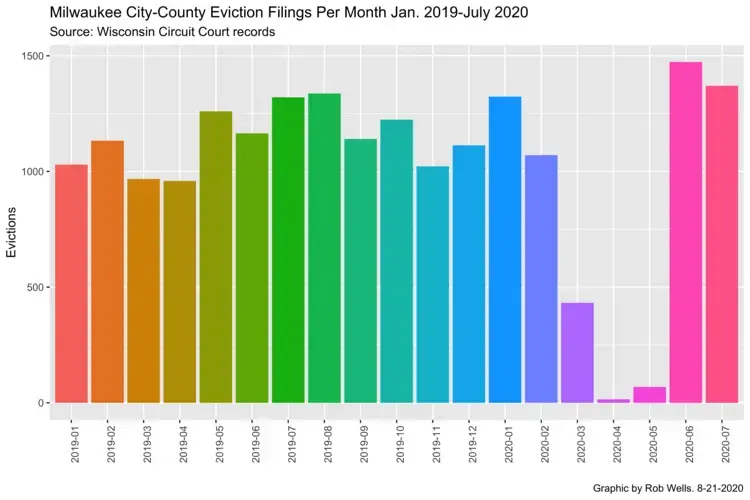

States across the country temporarily barred landlords from evicting tenants this year as the coronavirus reached the United States, forcing businesses to shutter and unemployment to spike. Wisconsin was one of the first states to lift its eviction moratorium on May 26. Milwaukee city and county tenants saw a surge in eviction filings — 1,370 cases in July, up from just 15 in April.

With the increased eviction filings, Milwaukee legal aid workers have seen their workload triple compared to pre-pandemic eviction cases.

“What you’re seeing right now is two crises colliding,” said Brad Paul, executive director of Wisconsin Community Action Program Association. “You’re seeing the preexisting housing crisis and COVID. It’s a lethal combination.”

Johnson’s eviction is an example of COVID-19 fallout, as well as of longstanding income inequality and systemic racism in Milwaukee. The Black median household income in Milwaukee has decreased by 30% since 1979, according to a 2020 study on racial inequality in the city from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. About 40% of African American renters, double the amount of white renters, in the Milwaukee metro area spent more than half of their incomes on rent, according to a 2018 study from the Wisconsin Policy Forum, a nonpartisan, statewide research organization.

“You have poor and low-income people who really care, who are still struggling (and) have to work two or three jobs just to pay rent,” said Jacqueleen Clark, an organizer with the Milwaukee Autonomous Tenants Union. “And with the pandemic now and no one’s working at full hours, it has become difficult.”

The state also has an overburdened unemployment benefits claims system, which has led many residents to wait weeks or months for checks.

Wisconsin Watch reported in late June that the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development had received some 3.4 million weekly unemployment claims in the 13 weeks ending in June 20 but paid just 2.5 million claims. The agency rejected 409,000 unemployment. There were some 509,000 claims yet to be processed, a batch representing about 151,000 people. The agency was in the process of adding more staff to deal with the backlogged claims.

Race plays a role in neighborhood composition and evictions, said Jason Geils, a Milwaukee Autonomous Tenants Union organizer.

“So, what you have is years of chronic redlining, racist superstructure here that continually repeats itself,” Geils said. “So, a lot of these things are class based, but they’re also so interwoven with racial politics.”

Redlining is the illegal practice of denying an otherwise eligible person a loan on the basis of their race, according to the federal Fair Housing Act. “Racist superstructure” describes embedded racism in governmental policies and corporate business practices, such as job and housing discrimination.

Milwaukee is both the nation’s most segregated metropolitan area and has the lowest rate of Black suburbanization in the U.S., according to a 2020 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee study.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, about half of the renters in Milwaukee County spent at least 30% of their income on rent, making them “rent-burdened,” according to the 2018 Wisconsin Policy Forum study.

Johnson, who is African American, said one example of her poor experience at the apartment involves lack of response from the maintenance staff, who she said treats her rudely and disregards legitimate complaints. She and her husband have complained for two years about a broken dishwasher, a missing front door on the building and other serious maintenance issues.

Johnson was angry the maintenance staff left her apartment without a front door for a day, and then replaced the door without a lock for three weeks. She responded by withholding their $745 July rent.

Multiple attempts to reach Berrada Properties by telephone and email were not successful. The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism data analysis of Milwaukee city and county court records found Berrada Properties and affiliates were responsible for 11% of all 19,420 Milwaukee city and county eviction filings between Jan. 1, 2019 and July 31, 2020.

Pete Koneazny, chief staff attorney with Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee, a group that provides legal representation for tenants facing eviction, has focused on Berrada cases for about a year. He described Berrada’s typical presence in court as “aggressive” and “sue first, talk later.”

Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee has been inundated because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Koneazny said. In 2019, Milwaukee Legal Aid typically received eight to 10 eviction intakes per week, Koneazny said. After the eviction moratorium lifted, Legal Aid attorneys began to receive 25 to 30 weekly eviction intakes.

High rent in Milwaukee’s lower-income neighborhoods has caused an epidemic of evictions for a long time, Koneazny said.

One of the nearly 1,500 Milwaukee-area residents facing an eviction in June was Wyconda Clayton, who lives with her 20-year-old daughter in a townhouse owned by Business Ventures Investments. She is facing her fifth eviction with the company since 2018, according to an analysis of online court data.

Clayton said her most recent eviction began when her home care service job was impacted by the pandemic and her mother’s illness.

To provide in-home care for her ailing mother, Clayton had to cut back on hours, she said. She has two clients and works 17 hours a week, making around $300 biweekly, which is not sufficient to cover $600 rent and food costs.

Conditions in Clayton’s duplex were harmful to her mother, and Clayton said that her landlord would not respond to her maintenance requests. Her mother died in April and Clayton began working a new job in May, she said.

Clayton tried to pay her landlord $1,200, a portion of her previously owed back rent, but her landlord would not accept less than the full amount of $4,200, Clayton said.

“We couldn’t go out of our house and everything was shut down, so what do you want me to do?” Clayton said. “I can’t make the government send me my money just to pay y’all.”

After waiting several months for government aid, Clayton said she finally received her unemployment benefits Aug. 4, but has not received her stimulus check nor her federal tax refund. Clayton also applied for rent aid through the Social Development Commission in May and received a $3,000 voucher July 21.

Clayton’s final court hearing for her eviction case was Aug. 7, and the commissioner issued a writ of restitution, or an eviction. Although Clayton had all of the rent money she owed, she said her landlord did not accept the rent aid from the Social Development Commission.

“I’ve been trying to call my landlord, let my landlord know, but he was refusing my calls,” Clayton said. “He didn’t answer my texts.”

Clayton said she has until November to move out of her apartment and is struggling to find housing for her and her daughter.

Legal aid and housing advocates say a significant portion of low-income tenants lack any legal representation. Although inundated with requests, Koneazny of Milwaukee Legal Aid estimated his group and Legal Action of Wisconsin represent about 5% of tenants in eviction cases, leaving the vast majority of Milwaukee residents without representation.

The Howard Center analysis of court records showed 21% of eviction cases in Milwaukee city and county had an attorney attached to the case, much higher than other states reviewed, such as Georgia, which had about 1% attorney representation.

In Milwaukee, tenants were seeking legal help more often since passage of the federal CARES Act. Prior to the CARES Act, just 10% of eviction cases had an attorney attached to the case. Legal representation is not required in Milwaukee’s small claims court.

Clayton, for example, does not have a lawyer for her eviction case. Instead, she is receiving help from the Milwaukee Autonomous Tenants Union, which Clark and Geils formed in March to organize tenants to protect their rights.

One unexpected benefit of the pandemic has been improved attendance by tenants at video conference court hearings on evictions, said Judge William S. Pocan, who oversees Milwaukee small claims court.

“People are now appearing, because they can do so from their home, and people with a smartphone can appear easily through Zoom,” Pocan told Wisconsin Watch in an interview. “It has allowed more people to contest things than before, which we weren’t expecting.”

Even if it doesn’t result in a tenant being forced out of their home, just filing an eviction can impact their ability to find a quality living situation in the future, said Nick Toman, a Milwaukee Legal Aid staff attorney. It can lead to ending up in properties with building code issues or problematic charges.

“Once that first eviction gets put on somebody’s name, they’re kind of in the eviction track with future landlords,” Toman said. “And they have a hard time getting out of it, so it’s more likely they will get an eviction filed again in the future.”

Clark, a former Berrada Properties tenant, said she started the tenants union after her own eviction last March. She was ultimately evicted for not making her rent payment due to being in between jobs, she said.

Clark had Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee representing her at the eviction hearing, but she lost the case. Afterward, Clark struggled to find housing and, as a result, was homeless for about a year.

Having an eviction on her record added to the hardship of finding quality housing.

“Now, finding housing because of the eviction, I had to pay double security,” Clark said. “Who can pay double security?”

Wisconsin Watch staff contributed to this report. Hennigan and Zimmardi reported for the University of Arkansas.

This project is a collaboration among the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, Big Local News at Stanford University, the University of Arkansas and Boston University. It was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center, the Scripps Howard Foundation and the Park Foundation.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.