With a victor named Goodluck and the appearance of fair and decisive voting in Nigeria, last year's presidential elections seemed to bring about a bit of hope. But things quickly unraveled.

Within days, there were chants and curses, killings and chaos. The voting, and the ensuing violence, cleaved to ethnic and religious lines. Goodluck Jonathan, a Christian from the economically advantaged south, defeated Muhammadu Buhari, a Muslim and former major general from the north, and when Mr. Buhari failed to concede, his supporters broke into a rhythm of riots and disorder.

Benedicte Kurzen, a French photographer who has been based in Johannesburg since 2005, came to Nigeria last year with a Pulitzer Center grant and a sense of the roiling tensions there: long-seeded resentments, rooted in the breathtaking disparity of wealth, widespread corruption and a pervasive, implacable fear.

"I was not expecting to be caught by the news so fast. We wanted to start by being introduced to the different dynamics," said Ms. Kurzen, who originally conceived of the project as an exploration of religion in the area. The project, which she calls "Nigeria, a Nation Lost to the Gods," will be shown at the Visa Pour L'Image festival in Perpignan, France, beginning Sept. 1.

Skeptical of the easy binaries of "north vs. south," "Islam vs. Christianity," rich and poor — as the conflict is conventionally presented in many news outlets — Ms. Kurzen, on several trips to Nigeria beginning in April 2011, sought to reveal an intricate underlying set of circumstances. "It's a convenient divide — it makes things a bit more readable," said Ms. Kurzen, 32, "but the reality is that it's way more complex than this. We should keep in mind that it's more complex than just 'northern Muslim impoverished uneducated forgotten north' versus the 'oil-rich, educated and entrepreneurial south.' "

"The differences are very striking," she said, "but from a political, ethnic, and social point of view, things are more intricate and codependent."

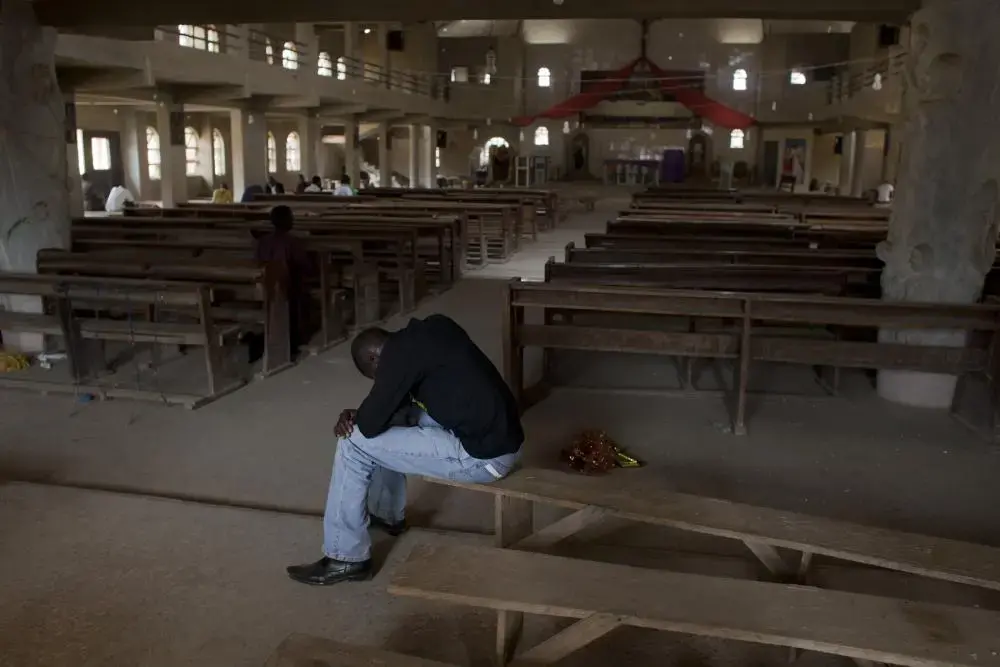

So intricate and codependent that documenting the situation in a way that supplied context or insight proved to have its limits for Ms. Kurzen. At its outset, the violence seemed politically motivated, though it soon fell along religious lines, and as it intensified, its causes became harder to discern. The resurgence of Boko Haram, an Islamist group that haunts the north, has added a confounding element. Mysterious and unflinchingly brutal, they conduct frequent bombings in Maiduguri and elsewhere, and they continue to terrorize and are difficult to track down.

Corruption, abuses of power and efforts by interested parties — the government, the military, Boko Haram — to present different realities mean that nothing could be taken for what it seemed. Regular bombardment against Christians raised the question of whether it was caused by Boko Haram or just thugs; violent reprisals against Muslims further obscured clarity. The local police, and the government, on some levels, sometimes projected ambivalence in dealing with Boko Haram's influence and destructive ways. Often, it wasn't even clear who was more afraid of whom.

"This is also the limits of photography in that sense; it only goes so far in understanding what's in front of you," Ms. Kurzen said. "I'm only photographing the symptoms of phenomena, of dynamics: symptoms translated through the daily life of the people. But I don't think I'll ever really know or really understand what's cooking underground."

In an image of four boys swimming, for instance, the relatively peaceful scene belies an acute and longstanding strife. The Kaduna River (which means "crocodile," from kada in the Hausa language) separates the Christian and Muslim neighborhoods, which have been essentially in continual conflict since the institution of Shariah law in Kaduna State in 2001. The riots in the decade that followed killed thousands. "There's always like a little twist to every picture," Ms. Kurzen said. "Even if it looks like a quiet moment, there is always something that is underneath the surface."

Indeed, the inclination is strong to hark back to easy definitions when seeking answers to grim, gauzy questions.

Ms. Kurzen — who has lived on the continent since 2005, when she moved from the West Bank — acknowledged the difficulty for some, in Africa and abroad, of seeing past preconceptions of Africa's myriad and intricate problems. For instance, many in Lagos, with its bustle and business, seemed oblivious to the conditions of living in the north, she said. And she acknowledged these challenges in herself as well.

"In some instances, I just say, 'I don't understand.' I'm not really upset with people who don't really know Africa and who haven't been here to challenge simplistic misconceptions, but that's what [journalists] are here for. To raise questions can be more important than to find answers."