- Cambodia’s largest island, Koh Kong Krao, off its southwest coast, is covered in largely untouched old-growth forest, but recent satellite imagery shows deforestation is spreading.

- Much of the forest cover loss is in areas tightly controlled by Marine Brigade 2, a navy unit stationed on the island that has historically been accused of facilitating the illicit timber trade.

- Residents of the island said the navy controls almost every aspect of life there, with provincial officials afraid to intervene or investigate the military’s actions on Koh Kong Krao.

- Cambodia’s military has long been a key factor in illegal logging across the country, and reporters found evidence of its continued involvement in logging across the Cardamoms.

*Names have been changed to protect sources who said they feared reprisals from the authorities.

KOH KONG, Cambodia — “I think there’s a 30% chance we’ll have trouble with the police,” said Ly Chandaravuth, an environmental activist with the outlawed group Mother Nature Cambodia.

This was in August 2022, when Mother Nature Cambodia was planning a trip to Koh Kong Krao, an island off Cambodia’s southwest coast in Koh Kong province, to raise awareness about the pristine ecosystems there.

But the group’s activism has had consequences, and Chandaravuth’s calculations, near one-in-three odds of being arrested just for visiting the island, were not unfounded.

On June 16, 2021, Chandaravuth, then a law student, was apprehended by police while collecting water samples from the Tonle Sap River in Phnom Penh. He’d planned to have the samples analyzed to better understand water pollution in the city. Instead, he was charged with plotting against the government, a charge that carries a sentence of up to 10 years in prison.

He was released in November 2021, along with five other Mother Nature Cambodia activists, three of whom had been in prison since September 2020. None were acquitted and all remain under judicial supervision for a three-year period. This means they are unable to leave Cambodia and are required to report to local authorities on a monthly basis.

Notably, they were warned against offending again. Yet this didn’t stop Mother Nature Cambodia from organizing what Chandaravuth described as an educational trip to Koh Kong Krao from Aug. 26-29, 2022.

“We’re just visiting, we have no demands, no message for the government and we have permission from the residents,” he said prior to the trip. “The government wants to keep the development of Koh Kong Krao quiet, so I think it will only look worse if they arrest us.”

The week of their planned trip, Mother Nature Cambodia petitioned the Ministry of Environment to release the findings of a 2016 study the ministry had conducted to assess whether Koh Kong Krao could be designated a marine national park.

That same year, global conservation authority the IUCN and its partner-led initiative Mangroves for the Future highlighted the value of ecosystem connectivity to Cambodian officials. This ultimately led to the island of Koh Rong, Cambodia’s second largest, acquiring marine national park status in 2018. But the environment ministry’s study into Koh Kong Krao remains unpublished, if it was ever conducted at all.

The only evidence to suggest a study had been conducted comes from a June 4, 2020, press release issued by the ministry just a day after Mother Nature Cambodia activists had been detained by police and had their bicycles confiscated while attempting to cycle from Phnom Penh to Koh Kong as part of an awareness campaign to save Koh Kong Krao. In its press release, the ministry said Koh Kong Krao would be a marine national park by 2021.

But this never happened, and Neth Pheaktra, spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment, couldn’t be reached to answer why, despite multiple attempts to contact him by phone and written questions sent over the messaging app Telegram.

Despite the lack of protection conferred upon it by the government, Koh Kong Krao, the largest of Cambodia’s 60 islands, is also one of its best preserved.

Spanning some 100 square kilometers (around 39 square miles), almost all of Koh Kong Krao is covered in old-growth forest that sprawls across mountains before giving way to waterfalls that connect to mangroves via creeks and estuaries, forming contiguous ecosystems with the seagrass meadows and coral reefs that fringe parts of the island.

Such a vast, verdant island untouched by large-scale investments makes Koh Kong Krao stand out from its peers off the coast of the Cardamom Mountains, many of which have been bought up by the Cambodian elite and seen their ecosystems degraded as a result.

Rumors of a tycoon typhoon on the horizon

While the government remains largely silent on the status of Koh Kong Krao, so too did the authorities during Mother Nature Cambodia’s trip to the island. Upon returning, Chandaravuth said that when he and the 24 people — some activists, others simply interested members of the public — arrived in Koh Kong province, police took photos of them “in case anyone goes missing.”

Other than this, he said, soldiers stationed on Koh Kong Krao watched the group for several hours, but there was minimal interference.

“We stayed with the fishing community in Alatang village, on the southeast of the island,” Chandaravuth said, adding that the community had agreed to host the activists and their guests beforehand. “It’s beautiful there, you can see many different species of fish, which provide for the community — and they want tourism to become a new income source, so there’s lots of options for trekking, there are waterfalls and parts of the jungle are so thick, there’s no sunlight inside. Big islands like this, they’re rare.”

Rare or not, the specter of unconfirmed rumors that the island has been sold to Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) senator and tycoon Ly Yong Phat, a Thai-Cambodian national, hangs heavy over Koh Kong Krao.

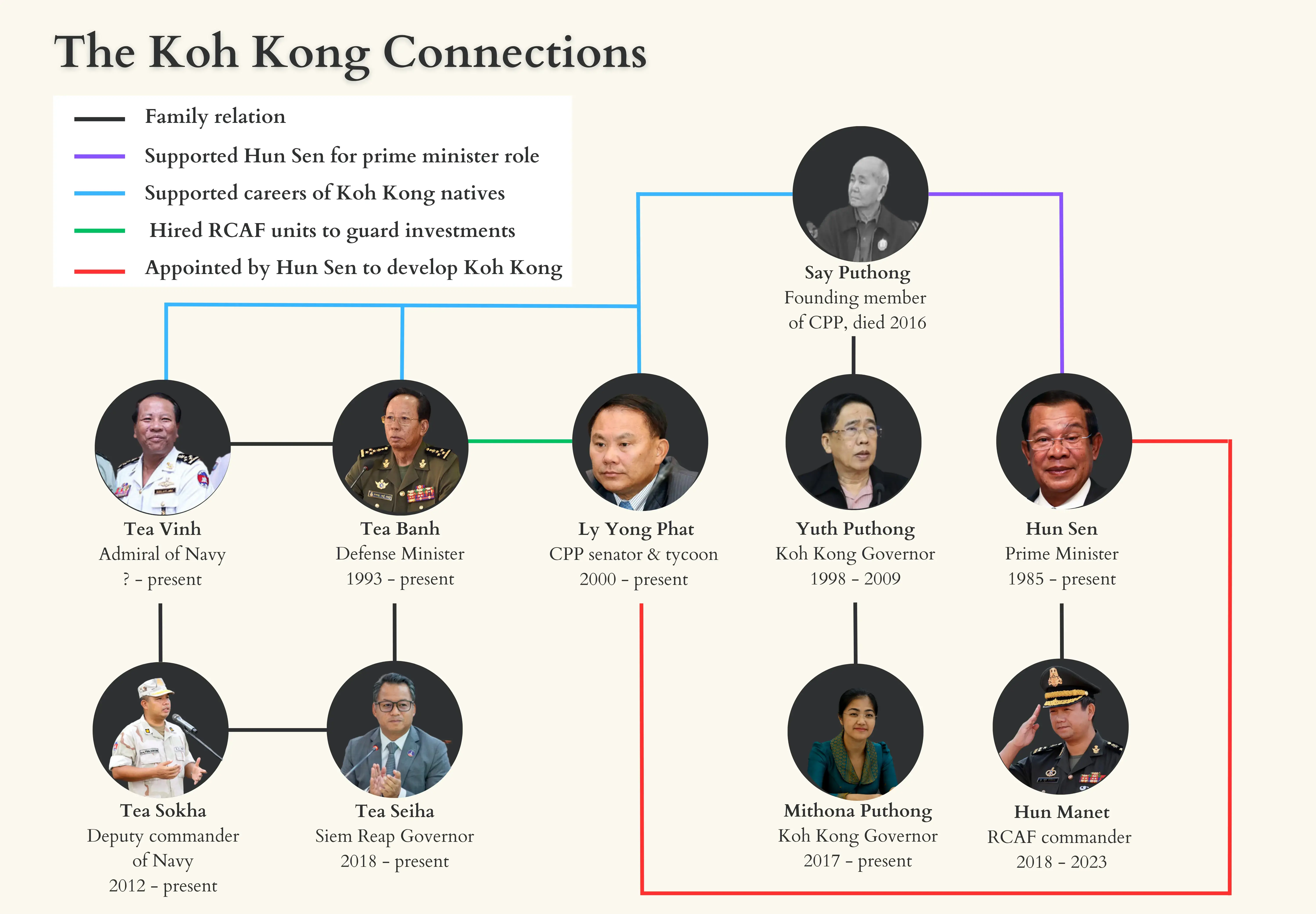

Ly Yong Phat was appointed by Prime Minister Hun Sen to develop the province of Koh Kong in 2000, and the prospect of a tycoon with a long record of forced evictions, illegal logging and environmental vandalism in Koh Kong — all in the name of economic development — has since made the island a target for Mother Nature Cambodia’s activism.

The government’s alleged decision to hand over Koh Kong Krao to Ly Yong Phat, who last year was appointed personal adviser to Prime Minister Hun Sen, appears to date back to 2014. Documents seen by Mongabay suggest that three companies, including Ly Yong Phat’s Koh Kong SEZ, applied for the license to invest in Koh Kong Krao, but it is unclear whether the license was ever issued or to whom.

L.Y.P. Group, the eponymous conglomerate belonging to Ly Yong Phat, did not respond to questions sent by Mongabay via email, and calls to the company’s listed phone numbers went unanswered.

When reached for comment, Sok Sothy, deputy provincial governor of Koh Kong, read messages sent in both Khmer and English before blocking reporters’ numbers.

In a 2020 interview with Radio Free Asia, Koh Kong Governor Mithona Puthong appeared to confirm that Ly Yong Phat had been granted the license to develop the island on June 14, 2019.

But when contacted in October 2022, Puthong said she misspoke in the 2020 interview and that no applications to invest in Koh Kong Krao had been seen.

“We have not received any letter of application [for investments] in 2019. I am sorry when I gave the answer — my apologies, I have asked my people to double-check,” Puthong said, adding that neither the provincial nor national-level authorities had received an application to develop Koh Kong Krao from Ly Yong Phat or any of his companies.

Some residents of Koh Kong Krao suggested that Ly Yong Phat had blocked ecotourism development projects on the island, with local authorities telling prospective developers that the island had already been promised to the Cambodian tycoon since 2019. Others recalled seeing Ly Yong Phat with people they believed to be Chinese investors visiting the island repeatedly over the course of 2022.

But while many of the island’s residents knew of Ly Yong Phat’s supposed purchase of the island, none had any idea about his plans.

Chandaravuth said that if Ly Yong Phat had indeed been given the island as a land concession, whether in 2014 or 2019, Article 62 of Cambodia’s 2001 Land Law requires investors to use their concession within 12 months of it being issued — something that clearly has not happened on Koh Kong Krao.

“Maybe they’re up to something, there’s timber, there are minerals, there’s wildlife, so we hope that our visit with tourists will make [Ly Yong Phat] think twice about what the public reaction will be,” Chandaravuth added. “They think if they just ignore us, the people’s voice will fade away, but we’ll keep defending Koh Kong Krao.”

When asked about Mother Nature Cambodia’s campaign to protect Koh Kong Krao, Governor Puthong said, “If they have concerns, it is their rights as youths.”

She again denied the island had been sold to Ly Yong Phat in a subsequent March 2023 phone interview.

“We haven’t received any letter from the Council for the Development of Cambodia yet regarding the development of Koh Kong Krao,” she said. “There’s a letter issued by the Ministry of Environment already, to begin making Koh Kong Krao into a protected area, we will support this.”

Koh Kong Krao under the gun

As it stands, Koh Kong Krao remains neither developed nor protected, but another faction presents a more immediate threat to the island, its ecosystem and its inhabitants: the Royal Cambodian Navy’s roughly 70-man Marine Brigade 2, permanently stationed on the island.

“The soldiers are trying to break the community,” said Chheng*, a fisherman who has lived on Koh Kong Krao for the past decade.

Sitting on the creaking remains of the island’s only pagoda in the island’s only village as the light faded one evening in November 2022, Chheng explained how the soldiers stationed on Koh Kong Krao exert a level of control over the island that even provincial authorities cannot rein in.

“The pagoda fell into disrepair, it’s falling apart, but the soldiers won’t let us repair it,” he said apologetically. “This is why I try to attract tourists to the island — to raise funds to rebuild the pagoda. It’s still crumbling though. If we have a strong pagoda, a strong school, maybe it will be the military who are evicted instead of us.”

But it’s not just the pagoda — the whole of Alatang village groans under the weight of the 73 families who call it home.

A cobbled-together collection of sun-bleached planks makes up the rickety boardwalks that hold the village together. The wide array of once-colorful boats that bob about in the water, paint peeling in the sea air, are moored to wooden houses sporting tin roofs, awaiting their next voyage in search of fish, shrimp and crabs.

“Marine Brigade 2 doesn’t want any villagers to cut trees for building houses without paying them, they want us all to do as they say,” Chheng said.

When asked whether he felt this was because the military wants to retain a monopoly on logging, Chheng said he asked the soldiers the same question.

“If you don’t allow us to cut, do you cut it for yourself? They didn’t answer,” he chuckled.

According to Chheng, the commanding officers of Marine Brigade 2 control the entirety of Koh Kong Krao and its infrastructure, including water, electricity and food deliveries.

“The military block people from coming to buy fish or seafood from Alatang village,” Chheng said. “They purposefully close our economy so they can buy from us at a lower price.”

Other residents of Alatang village confirmed Chheng’s allegations. Sophal*, another fisherman who has lived on Koh Kong Krao much of his life, noted there was no higher authority they could turn to, saying that complaints to officials in Chroy Pros commune or to Trapeang Rung district hall have been met with silence.

“When we speak to the commune chief, we’re told they will ask the provincial authorities, but nothing ever happens,” Sophal said. “Last time, the soldiers told us that if we cannot live here like this, then we must leave.”

As Koh Kong Krao is state-public land, none of the residents of Alatang village are even allowed to live there. That leaves them relegated to a precarious life on the wooden structures just off the island’s coast that deprives them of farmland, forcing the villagers to rely on the military-controlled groceries and deliveries.

“Nobody is allowed to build a house on the land, because the whole of Koh Kong Krao is under the control of the military — even the beaches,” said Seng Hak, the CPP-aligned chief of Alatang village, who has lived on the island for more than a decade. “I’m supposed to be the head of the village, but the soldiers have weapons, so their presence is more powerful than mine.”

Residents’ attempts to reason with the soldiers saw them referred to the Ministry of National Defense, but those who were interviewed said they had been unable to successfully contact the national government body and most said they had no idea how to.

‘They make their own rules’

The navy has centralized its power in the northern portion of the island, within an area that Mongabay reporters were not allowed to access or even dock a boat. What is known locally as First Beach is entirely off-limits, even to Alatang villagers.

“If you fly your drone here, the navy will shoot it down and arrest us all,” cautioned a fisherman who agreed to take reporters around the island by boat.

It is also here, residents of Alatang village alleged, that the navy runs an illegal logging operation. Oversight and scrutiny have been historically uncommon among Cambodia’s military, but in a place as remote as Koh Kong Krao, those with weapons are in effect above the law.

“The military come from the citizens, they’re originally just normal citizens that would come under our authority, but now they’re soldiers, they make their own rules,” said Hak, who noted that the Ministry of National Defense holds more power nationally than the Ministry of Interior, which he works for as the Cambodian People’s Party village chief.

Satellite imagery analysis shows that between May and June 2019, a road was carved through the dense jungle that stretches from the northwest tip of the island down past First Beach and Second Beach. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, when residents confirmed nobody was allowed to visit the island, patches of forest vanished within the military-controlled area.

Throughout 2022 and 2023, evidence of selective logging became visible via satellite imagery, matching deforestation alerts seen on data visualization platform Global Forest Watch. These small, bald patches poking through the forest canopy can be seen dotted about the northwest of the island, but also running down the western coast of Koh Kong Krao, down to its southwest corner.

“We cannot identify the loggers, we have no evidence to prove who they are, but we know that they are brought in by the military. They use the creeks in the island to enter the forest,” said Chheng, whose fishing routes take him all around the island.

These allegations match claims made by Hong*, an unemployed logger in Koh Kong town on the mainland, who previously worked for a network of timber traders based out of the Koh Kong provincial prison.

“When they [the prison logging network] sent me to find rosewood, it was mostly to Koh Kong Krao,” Hong said in a July 2022 interview.

Hong’s description of his experience logging on Koh Kong Krao matched the observations of Chheng: Hong claimed to be taken out on a boat from mainland Koh Kong by soldiers, who protected him and his team as they traveled through the island’s creeks to access untouched forest where valuable timber is still hidden among the mountains.

“Whenever we go to log on Koh Kong Krao, we have protection from RCAF [Royal Cambodian Armed Forces],” Hong said. “The timber from the island goes either to Thailand or to Sihanoukville Port, that was how it worked when I was there last year.”

Hong said he didn’t know the names of the naval officers who facilitated his logging on Koh Kong Krao, but was able to confirm roughly where he had landed on the northwest of the island, where access is restricted to military personnel.

“It would be utterly impossible for this logging not to be, if not outright perpetrated by RCAF soldiers, happening without the approval of military commanders of the region,” said Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson, the founder of Mother Nature Cambodia.

Gonzalez-Davidson was deported and barred from returning to Cambodia in 2015 for his role in Mother Nature Cambodia’s ultimately successful opposition to a hydropower dam being built in the Cardamoms, but he has maintained close contact with those working in Cambodia’s southwest.

“The fact that it has always been, with the exception of the last couple of years after the beginning of the arrival of tourists, a place where soldiers were there pretty much alone,” he said. “[This] means that large and expensive species of timber became obsolete [on Koh Kong Krao] even faster than in other forested parts of the country.”

But Gonzalez-Davidson said that while rosewood species have been largely annihilated on Koh Kong Krao and almost everywhere else in Cambodia, navy officers could still sell what’s left to bolster their meager paychecks.

“Having said that, the fact that logged timber needs to be transported out by boat as opposed to by land, has also perhaps helped preserve some of the large trees you still see in the island,” he added, noting that this would add to the costs of transporting the timber.

Off the coast and off the books

“Now, I’m preparing a boat for Em Chantha, who asked me to build it to supply merchandise for the marine officers off Koh Chhlam [Shark Island]. He’s the commander of the Marine Brigade stationed on Koh Kong Krao,” said Chea*, a boatbuilder by trade who has called the island home for almost two decades. “They hire other people to supply the timber, to go and cut the trees here on the island.”

Chea was hesitant to discuss the legality of taking timber from Koh Kong Krao — or much of anything. Like other residents on the island, Chea said he lives at the mercy of the soldiers, noting that “Technically, nobody is allowed to live here.”

According to Chea, Chheng and other residents, Koh Kong’s coast appeals to the navy beyond purely strategic locations. Islands off the coast of Koh Kong have provided a key outpost through which timber smuggling could be facilitated by boat, with various levels of complicity within the navy.

“We used to have a lot of rosewood across the province, but now it’s mostly gone,” Chheng said. “But the island still has other valuable species, like beng [Afzelia xylocarpa], although this is disappearing from Koh Kong [province].” Beng has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 1998, with the species’ distribution across Southeast Asia dwindling in the face of huge demand for luxury furniture, for which beng provides a valuable substitute to rosewood.

Across the board, conservationists agree that rosewood has been essentially extirpated from Cambodia’s forests, most of which have already been picked clean of the most valuable grades of timber. This is where Marine Brigade 2 appears to come in, at least in the context of Koh Kong Krao. Its alleged involvement in Cambodia’s illicit timber trade is a reflection of the accusations that have dogged the RCAF for decades.

Chantha, the island’s highest-ranked officer, has been accused of illegal timber smuggling since at least January 2014, back when he was deputy commander of Marine Brigade 2 serving under Tep Vuthy, who now serves as deputy commander at the controversial Ream Naval Base. The pair were accused by local fishermen of stockpiling illegally harvested rosewood on Koh Kong Krao in preparation for its sale to Vietnam, relying on their military ranks and political allies in Koh Kong province to guarantee its safe passage. These allegations were repeated the same year, with the marines reportedly receiving support from then-chief of the Koh Kong provincial gendarmerie, Thong Narong.

The gendarmerie is supposed to police the military, but in reality, this role has reportedly often been abused across the country and throughout the gendarmerie’s ranks, with numerous reports of collusion between the gendarmerie, the military and illegal loggers — particularly along Cambodia’s borders.

The long-standing coastal timber smuggling operation, residents of the island said, was aided by the rotation of personnel between Marine Brigades 1 and 2, with Marine Brigade 1 stationed on neighboring Koh Yor, an island connected to Koh Kong’s provincial town by bridge.

Rotational duties were confirmed by a soldier who blocked Mongabay’s reporting team from docking at First Beach.

“Every three months I get transferred over to Koh Yor and then back here again three months later,” said the soldier, who would not identify himself. “We serve the people, because we are the military, but when people ask for trees to help them repair their homes or the bridges, I don’t understand why the military chief doesn’t allow it.”

Media reports from 2013 suggest that the navy-controlled Koh Yor has been used as a secondary stockpile location for rosewood, leading to shootouts between Cambodian gendarmerie forces and corrupt navy officers involved in the timber trade.

Pro-government outlet Koh Santepheap reported in 2018 that a truck full of luxury timber was detained in Koh Kong’s Trapeang Rung commune, having traveled from Stung Treng province in the northeast of Cambodia. Rangers from conservation NGO Wildlife Alliance, which works with gendarmerie and Ministry of Environment rangers, stopped the truck, but provincial officials reportedly intervened and ordered the truck be allowed to continue to its destination: the naval base at Koh Yor.

By 2016, Chantha had been promoted to commander of Marine Brigade 2 and cast off any doubts that his alleged role in transporting illegal timber had been solely down to his former superior Tep Vuthy.

Local media that year reported that Chantha sat at the helm of a timber smuggling operation, allegedly with Forestry Administration officials paid to turn a blind eye. The same year, a military official known as Tha was again accused of smuggling neang nuon (Dalbergia oliveri), a prized rosewood species, out of Koh Yor with intent to sell to Vietnam.

The case was eventually investigated toward the end of 2016, with police sources confirming that Tha was a naval officer who had conspired with a local police officer to transport rosewood to islands off the coast of Koh Kong in preparation for shipment to Vietnam. It is unclear if charges were ever filed against anyone reportedly involved.

The impunity with which RCAF units and their commanding officers have been able to extract valuable timber from across Koh Kong and sell it either domestically or abroad is something that activist Gonzalez-Davidson said is afforded by a network propped up on kickbacks.

“All units, and by extension soldiers, have the unofficial right to exploit whatever natural resources they see fit, as long as payments up the chain of command are given of course,” he said. “The extraction of rosewood of 2010 to 2013 or so, which I saw with my own eyes time and again, was a good example of this.”

During this time, he said, RCAF units were deployed across the Cambodian sections of the Cardamoms to facilitate, and to take a cut of, the multimillion-dollar timber trade that was driven by China’s insatiable appetite for hongmu furniture made of rosewood and abetted by Cambodia’s lax environmental safeguards. The RCAF’s involvement, Gonzalez-Davidson said, was happening independently, without orders from Phnom Penh.

Many residents, including Chheng, remained sympathetic to Chantha, despite the long laundry list of allegations linking him to illegal logging — many made by the community on Koh Kong Krao itself — saying that things improved significantly for them in the transition from Tep Vuthy’s command to Chantha’s.

“Em Chantha took over and he is better, he tries to help people,” said Chheng on the rotten wooden steps of the island’s pagoda. “Chantha used to work for [ruling party senator and tycoon] Ly Yong Phat as a logger, he would bring in a lot of timber, leftovers from other jobs, and then he would sell the timber cheap here so we could build the primary school.”

Fifteen years ago, Chheng recalled, Chantha had not donned the RCAF uniform and was limited by the lack of education opportunities. He freelanced in the forest for Ly Yong Phat, working with navy officials at Koh Yor, until he became one of them.

“He has no other skills and his network is in the military,” Chheng said. “In Cambodia, if you have a network, you can do anything.”

Nobody on the island dared to share Chantha’s contact details and reporters were barred from accessing First Beach, where Marine Brigade 2 is headquartered, making it impossible to visit him in person to verify these claims.

Koh Kong provincial officials said it was a matter for the Ministry of National Defense, but Chantha’s contact details are not listed on the ministry’s website and repeated calls to numbers listed as the ministry’s information department went unanswered. Likewise, messages sent to Chantha’s Facebook page were met with silence.

Neither Gen. Chhum Socheat, spokesperson for the Ministry of National Defense, nor RCAF spokesperson Thong Solimo would answer questions about Chantha, Koh Kong Krao or the military’s role in the illicit timber trade when reached by phone, and neither responded to detailed written questions submitted by Mongabay.

Cronies of Koh Kong

In a March 2023 phone interview, Koh Kong Governor Puthong ultimately noted that she was powerless to intervene in matters concerning the RCAF.

“This area is controlled by the military,” she said of Koh Kong Krao. “I don’t know what to say, the military is in charge there because they live there. That’s the right of the military, I cannot touch it.”

This is particularly telling given Puthong’s relationship to Koh Kong province, which has only been accessible by car since 2002 when CPP senator Ly Yong Phat bankrolled the bridge that linked the coastal province to the rest of Cambodia. The isolation, coupled with the low population density and proximity to Thailand, has factored into the rise of the Thai-Cambodian elite that form Koh Kong province’s semi-separate political climate.

Taking the role of provincial governor in 2017, Mithona Puthong became the latest in a long string of influential figures from the Puthong family; she is the daughter of Yuth Puthong, who himself served as governor of Koh Kong. Both Mithona and Yuth are overshadowed by the imposing legacy of Say Puthong, Mithona’s grandfather, a founding member of the CPP, believed to be the party grandee who nominated now-Prime Minister Hun Sen for the top job in 1985. Both Hun Sen and the CPP remain in place today. While Say Puthong died in June 2016, an event that produced one of the few known images of Hun Sen crying in public, his legacy is still keenly felt across Koh Kong.

In addition to being accessible by car to Cambodians for just 21 years, Koh Kong has only been Cambodian for 119 years — a short period given the country’s long history — since French Indochina took control of parts of what is now Trat province, Thailand, in 1904. The French returned control of Trat to Thailand in 1907, but Koh Kong remained a part of French Indochina, before Cambodian independence from France was declared in 1953 and it became its own Cambodian province in 1959, while retaining a strong connection to Thailand.

This is how Say Puthong, a Thai national, came to be so involved and influential in Cambodian politics. He used that influence to mingle with other ethnically Thai Cambodians, like Tea Banh, a native of Koh Kong whose life has been dominated by conflict — first rising up against then-prime minister Norodom Sihanouk, then against the subsequent administration of Gen. Lon Nol, before joining the Khmer Rouge and then the Vietnamese forces that ousted Pol Pot’s genocidal regime.

Now, for almost 20 years, Tea Banh has served violently as defense minister and one of Cambodia’s 10 deputy prime ministers, while his brother, Tea Vinh, is admiral of the Royal Cambodian Navy.

“Given the many links between the Tea family and Thailand, it would be only natural for them to strike financial links with Thailand,” said Mother Nature Cambodia founder Gonzalez-Davidson. “More so in the early 2010s when rosewood and other types of timber was so expensive and so easily available.”

And so for Koh Kong Krao, where the murkiness of political, military and economic interests merge to obscure reality, Gonzalez-Davidson suggested that the selective logging could be either a means for navy commanders such as Chantha to make extra cash from the remaining timber species, or a more broadly orchestrated plot to secure land as its value rises, particularly ahead of an investment by Ly Yong Phat.

“It could, however, also be yet another case of RCAF commanders identifying the value of the land for future development and thus claiming it for their own,” he said. “The navy’s main reason for claiming Koh Kong Krao was not only to make as much money as possible out of the timber and wildlife, but also to get access to land that can eventually become very expensive.”

The arm that controls the hand that controls the fingers

This nexus of political, military and economic control is felt across Koh Kong, even in places as remote and sparsely inhabited as Koh Kong Krao.

“Em Chantha is the commander of Marine Brigade 2 and he’s Khmer,” Chheng said. “But Ta Fiang is the deputy and he has more power, even than Chantha.”

Ta Fiang proved to be another elusive character in the hyperlocal power plays of Koh Kong Krao, but multiple residents gave the same account of him: a Thai national, able to speak broken Khmer, who purchased the name of a deceased soldier to gain a military rank and salary.

The buying and selling of soldiers’ “names” is not uncommon and dates back to the United Nations’ involvement in Cambodia during the 1990s, when Cambodian military commanders would inflate the number of soldiers under their command to gain additional financial support. A 1999 internal investigation conducted by the Ministry of National Defense found some 13,000 “ghost soldiers” whose existence was confined to paper. These problems, Cambodian officials argued in 2002, were known to international donors, but ignored in favor of demobilizing the RCAF in the wake of an official end to the conflict in Cambodia.

Still, in 2008, a further 10,000 ghost soldiers and another 10,000 ghost police officers were uncovered by the government. Then, in 2010, the government abandoned the donor-funded demobilization after donors such as the World Bank grew frustrated by the apparent lack of results.

As such, the sale of ranks and salaries is believed to continue in remote parts of the country far from the reforms issued in Phnom Penh, and Ta Fiang has, according to Koh Kong Krao residents, fully capitalized on the lack of oversight across the island.

“He cannot read or write Khmer, he can only speak Khmer, but he has connections, so nobody dares to touch him,” said Chheng, the fisherman.

“Anywhere he goes on Koh Kong Krao, people are scared of him because he knows everyone, everyone knows him,” said Sophal, another fisherman who confirmed Chheng’s assessment of Ta Fiang’s path to power.

Chheng alleged Ta Fiang owned a coconut farm on the south of the island and then brought in loggers to clear several more hectares around the farm, where satellite imagery shows evidence of more selective logging.

It is Ta Fiang’s Thai ties, including his Thai wife, that have reportedly earned him connections to Tea Vinh, head of the navy, and several villagers confirmed that Ta Fiang’s wife has repeatedly bragged about delivering shrimp to Tea Vinh’s house in Peam Krasop.

When reached by phone, Ta Fiang used one-word answers to reporters’ questions and denied purchasing the name and rank of a deceased soldier. He also denied owning the coconut farm that had seen several hectares of forest cleared on the island’s southwest, refuted that any logging had taken or was taking place on the island, and rejected claims that the navy was facilitating transport of outsiders into Koh Kong Krao to fell trees. When asked about the documented involvement of his boss, Em Chantha, in illegal logging, Ta Fiang told reporters to “Go ask him” before hanging up.

“If Ta Fiang says no, then [Chantha] cannot do anything, but they’re both in the network of Tea Vinh,” Chheng said. “[The marines] are all part of the network of Tea Vinh, they are his fingers, he is the hand, Tea Banh’s the arm.”

Both Defense Minister Tea Banh and Admiral Tea Vinh are ethnically Thai and grew up on Koh Sralau, a small island barely half a kilometer north of Koh Kong Krao that sits within Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary.

But Peam Krasop, like much of Koh Kong’s protected areas, have suffered at the hands of the Tea family, whose recent land-grabbing spree reflects their outsized influence within the provincial political economy that translates to broader power nationally.

Both the Tea brothers have a long history of involvement in illegal logging across Koh Kong that dates back to the late ’90s, with navy chief Vinh being hit with Magnitsky sanctions by the U.S. Department of Treasury in November 2021 for alleged corruption in connection to a controversial military base being developed with Chinese assistance inside Ream National Park. The park itself has subsequently been devastated by further Chinese investments, much of which are believed to be linked to the Tea brothers.

When reached for comment, Tea Vinh said he was “in a meeting” and then subsequently declined multiple calls from reporters. He did not respond to detailed written questions submitted via the messaging app Telegram. The admiral’s brother, Tea Banh, could not be reached, and Ministry of National Defense officials refused to share his contact details.

A problem beyond the province

The Tea brothers’ Thai connections have endured throughout successive generations of Puthong political dominance in Koh Kong province and have also helped the military maintain a close connection with another Koh Kong native, Ly Yong Phat. The latter is currently engaged in the development of a deep-sea port in his Koh Kong SEZ, in Kiri Sakor district on the coast of the mainland directly east of Koh Kong Krao, and the construction of a new bridge connecting Koh Yor to the Koh Kong mainland.

These aren’t Ly Yong Phat’s only connections to the military. While he doesn’t appear to have served or fought for the RCAF, he has hired them. A 2010 subdecree legalized the hiring of border security forces in a bid to boost military funding saw tycoons such as Ly Yong Phat take up the offer. At least two battalions, Battalion 42 and Battalion 313, hired by the senator have been identified carrying out armed evictions. While these troops cleared land for Ly Yong Phat’s business interests, others, including Battalions 42, 301, 302, 303 and 702, are also known to have been hired by the CPP senator.

Ly Yong Phat was not the only tycoon known for hiring the Cambodian military to advance his business interests in an armed fashion, but the practice is widely believed to have been informalized since 2016, relying on relationships rather than government policy or approval. This appears to have been further compounded by the alleged politicization of the RCAF in 2015, when the CPP added as many as 80 high-ranking party loyalists to the top ranks of the military, effectively ensuring it remained loyal to the ruling party and its allies.

Timber magnate Try Pheap, another Cambodian tycoon famed for his plundering of the Cardamoms’ rosewood species, was also found to have hired a range of RCAF units. But long after the ability of tycoons to hire soldiers ended, there remains evidence to suggest the relationship continues unfettered in Pursat province, another key element of Cambodia’s stretch of the Cardamoms.

The logging operations taking place on Koh Kong Krao are but a fraction of the RCAF’s known involvement in the illicit timber trade, and while the RCAF’s historical involvement in illegal logging is well-documented, reporters uncovered a previously unknown sawmill located within the Military Region III headquarters in Kampong Speu province, the tail end of the Cardamoms in Cambodia.

Cambodia is divided into military regions, each aimed at covering a number of the country’s 25 provinces, with Military Region III consisting of Kampong Speu, Kampot, Kep, Koh Kong, Preah Sihanouk and Takeo provinces. But the headquarters’ logging operation was an open secret among Kampong Speu residents.

“Sometimes we see timber taken into the military base, mostly at night, some of it is just cooking wood, but sometimes also they get big pieces of timber,” said Nithy*, a café owner whose property overlooks the road leading into the main entrance to Military Region III headquarters. “They have machines inside the base, a big saw, to process the wood, but I don’t know what they do with it afterward.”

The vehicles transporting the timber in don’t sport the recognizable blue-and-red RCAF license plates, Nithy explained — all the timber is brought in via minivan.

A man who declined to be named, but who operates what appeared to be a woodwork shop that backed onto Military Region III headquarters’ sawmill, and that is connected to the sawmill by a gate, claimed not to know about any logging activity. He also denied that he was a soldier, despite the RCAF football shirt he was wearing denoting his membership in an RCAF football team. The man would not let Mongabay reporters access the sawmill via the gate on his property, stating that, “There is nothing to see.”

When reporters attempted to speak to soldiers inside the headquarters, one reporter was physically detained and dragged across the street. The situation was defused while the first soldier called in a superior officer.

“Sometimes a car from outside or a truck carrying wood comes here,” the first soldier said. “High-ranking soldiers are the ones who buy the wood, but I’m not sure where they put all of it.”

While he couldn’t be sure, the first soldier suspected that the timber came from Phnom Aural, a mountainous protected area that has reportedly been heavily logged by military officials. Perhaps it would be used for a new building within the headquarters’ compound, he added.

“People in this area have been cutting down trees since before you were born, but soldiers no longer cut down trees as our salaries have increased up to $600 per month,” the first soldier said, adding that any soldier found to have committed a forest crime would be fired immediately.

However, while the first soldier reporters encountered openly admitted the existence of a sawmill within the military compound, his superior, who declined to give his name or rank, denied such a place existed.

“Soldiers are no longer involved in logging. Other crimes have stopped too now that the wood is no longer available in the forest,” he said. “This is a secret place that nobody is allowed to photograph.”

He repeatedly denied that timber was processed inside the military base, contradicting his subordinate and photographic evidence collected by Mongabay.

The unnamed second soldier then went on to suggest that “the enemy could be sat in front of us right now,” but maintained that soldiers, and the RCAF more broadly, had been reformed since Prime Minister Hun Sen’s eldest child, Hun Manet, was appointed head of the army. Rules were stricter, soldiers more disciplined, and corruption no longer tolerated, the second soldier claimed.

“Firstly, soldiers do not commit these crimes anymore because they are paid better; secondly, the new head of the military is much stricter than before; and thirdly, there is no forest to log nowadays,” he said.

When asked why, then, residents living around the military base reported seeing timber delivered to the base and why so many others had confirmed the existence of a sawmill with what conservationists suggested could well be a grade of luxury timber processed inside it, the second soldier was incredulous.

“If people say soldiers sell drugs,” he snorted, “do you believe we sell drugs?”

Mongabay did not find any evidence of drug sales at the Military Region III headquarters, but the evidence of timber is not something that the soldiers outside the base or RCAF spokesperson Thong Solimo were prepared to discuss. Solimo now appears to have blocked reporters’ numbers. Chhum Socheat, the defense ministry spokesperson, again did not respond to questions, or accompanying photo evidence, about the RCAF’s involvement in illegal logging.

“It is once more indicative of how the needs and agenda of criminal structures within the [military] is more important than the law, or even of official policies,” said Mother Nature Cambodia’s Gonzalez-Davidson when presented with this evidence. “Ultimately, though, this is what has been happening in the country’s forests for a long time, so nothing surprising.”