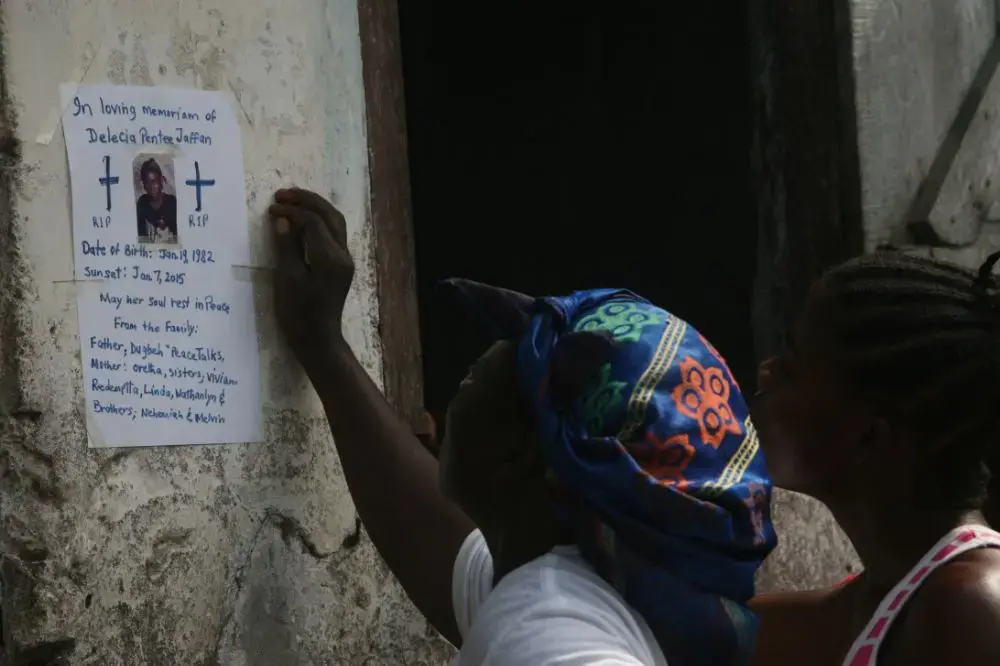

Delecia Pentee Jaffan is dead. On the white sheet of paper attached to the door of the 32-year-old's crumbling home in Monrovia's Bong Mines Bridge area, childlike blue handwriting read "Sunset: Jan. 7, 2015." Her father said that she had been sick for seven years. But this is what families say. Maybe she has been, or maybe she died from Ebola. Either way, the body is treated the same way.

To help curb the spread of Ebola, the Liberian government in August ordered mandatory cremation in Monrovia — an announcement that offended the Liberian soul to its core. Families in the West African country make annual pilgrimages to visit the graves of their deceased ancestors; when their bodies are incinerated and stored in large collective bins, this sacred rite is stripped. Liberian funerals involve washing the body, styling the hair, and dressing up the deceased. And the family members clean their own faces with the same water in which they washed their loved one. There are really few better ways to catch Ebola.

Cremations have mercifully ceased since the start of 2015, as a new safe burial procedure has finally been implemented at a remote site about 25 miles away, known as Disco Hill. Average Liberians are still scared, however, that when teams in white suits and masks and goggles come to collect a body, they will be forced to give up their loved one for the oven.

Mark Korvayan, 36, is an agriculturalist from Liberia's Lofa county who has been picking up the bodies of those who have died of Ebola since the disease came to his community in February. Despite a lack of training, he decided to forge ahead with the work as the situation in the region worsened. Eventually, he received some instructions: a line of photos stuck to a wall indicating what he is to do when picking up a body. Official Ministry of Health training followed, and now he does the job for the Liberian Red Cross.

Just before 10am on Thursday morning, dressed in blue paper scrubs, battered white boots, and a Dodge Charger visor, Korvayan ate a breakfast of chicken and fried rice as his call list came in from the Red Cross dispatcher. A few minutes later, his four-vehicle convoy was racing through in the center of the road in central Monrovia with their flashers on to a corner of Bush Rod Island, where the body of Delecia Jaffan lay.

The first sign of trouble appeared early, as Jaffan's family was not waiting at the meet-up spot next to the main road. In order to hunt down the home, Korvayan directed his trucks into the slum, down a narrow alley. There, he found a father and husband unwilling to give up their dead loved one.

Korvayan entered the small home and explained the process to the gathered men and women, answering questions, soothing, cajoling, and arguing both loud and soft about the need to give up Jaffan for safe burial. The family's sticking points were clear: how do they really know she will not be burned? And do they need to pay Korvayan for taking the body?

Traditionally, undertakers in Liberia will accept payment for the pick-up and transportation of remains. This system has been perverted as Ebola has wreaked havoc on the country, and while officially none of the non-governmental organizations that do body transport accept money, locals say that some burial teams charge up to $150 to take a body — or thousands of dollars to leave it and forget they ever came.

Korvayan was adamant where he stood on the matter. "We are not asking for money," he said. "If anyone comes asking for money, do not give it to them. We are paid to do our jobs. We are no longer cremating."

Dugbeh Jaffan was as sick as his daughter, but with symptoms that may indicate a cancer diagnosis. His eyes were watery. His body looked hollowed out, with his fingertips deep red and corroding and his feet leprous, and folds of skin stuffed in Crocs. He was covered in flies.

"Yesterday," he said. "I did nothing but cry."

Dugbeh gave in easily, but Abraham Rogers, his son-in-law, stood his ground. He would not give up his wife's body. Korvayan stalked the small lot adjacent to Rogers' home. "If they refuse, we leave it!" he said to himself as much as anyone. "I will not take five or ten dollars from anybody. It is not a blessing."

Finally, though, his impatience overcame his manners, and at the corner of the home he took Rogers aside.

"My brother, you know me," he said. "You know me good. I will show you the place. Everybody will be crying. People will be recording." Here he pointed to the photographer accompanying me and her camera. "There is no alternative."

"You are welcome," the husband said, completely defeated, and Korvayan immediately waived over his deputy.

The burial and spray teams moved extremely fast, dressed in Tyvek suits, masks, and wearing three gloves on each hand. One took a swab sample from Jaffan's mouth. The family will be notified in about two weeks if she tested positive for Ebola. The team of four men and two women placed her corpse in a body bag, carried it outside, and loaded it into the flatbed. They then sprayed down the house, removed the bedding for disposal, and cleaned themselves in an elaborate procedure of undressing. It's a job that takes strength and stamina.

"Simple mistake, you gone," Korvayan said.

Family and friends waited outside and watched the entire process. One woman, Mother Catherine, grew upset and suddenly started spinning and screaming next to the truck that bore her sister-in-law.

"My children!" she yelled over and over, eyes closed. No one moved to restrain her or join in. Then she sang part of a song, "In Jesus' Name," and testified for the assembled friends and family about the mercy of God.

Korvayan has dealt with worse — he's even been stoned and chased out of neighborhoods. When families start to indicate they'll get even slightly violent, he tells them to keep their distance at several feet away from him.

"I don't care how you feel about me, but give me feet," he said. No touching.

With the cargo loaded, the next stop was Disco Hill, a new 25-acre graveyard just purchased by the Liberian government and operated by the US-based non-profit Global Communities. The local leaders sold the land under the condition that the town receive a new road, primary school, and that its residents get preference for gravedigger jobs. Every county is responsible for burying its own dead, and only Montserrado County, the home of Monrovia and 40 percent of the Liberian population, had been without a safe area to place those who may have Ebola. This led to the hated cremation order, which was held until Disco Hill opened in late December.

"This solves a huge problem," said Matt Ward, the American site manager of Disco Hill. "Before, someone would go to an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) and the family would never see them again. They died and went straight to the incinerator." He shook his head.

"Desaparecidos," he said, using the South American term for the disappeared.

Ward is a self-described "cemetery guy," whose last job was in public health work in South Sudan. He is tall and unshaven, and sunburned after weeks of overseeing jungle removal and the pouring of concrete. The work has worn on him, but he has a system.

"I pick one to mourn," he said. "For me, it's an eight-year-old Muslim girl from Cape Mount. I don't want to say her name. I mourn her. The rest are just numbers. They have to be. Eighty Christian, 27 Muslim. 37 females, 70 males. Nineteen under the age of 10."

At the current rate of burials, Disco Hill has several years of space available. There are longer-term plans to make the site a national cemetery, and to establish a national monument with the names of everyone cremated. It would at least give families a place to visit on Decoration Day, an important holiday in mid-March when the graves of ancestors are painted. For now though, Disco Hill is dirt and fresh holes and a few trees. A Muslim section facing Mecca is separate from the Christian section, and there are yards of fencing demarcating safe areas from hot zones where the body bags are handled.

By the time Jaffan's body arrived, Rogers and his friend Tennessee were waiting. They sat on a wooden bench in a round hut made of branches and a white plastic tarp. The trip took them over an hour, and cost 300 Liberian dollars (US $3.24). This is a small fortune when a roadside bag of water is five dollars. They changed taxis three times.

Here Korvayan changed roles, from body removal team leader to funeral director. He took Rogers aside and told him the process: when it was time, he could approach the grave and pray for only one minute.

Rogers waited in the sun. A Global Communities decontamination team carried the body to the grave and lowered it in. Then they cleaned their gloves with a chlorine hand-pump over the open hole, the water dripping on the bag.

Rogers stepped forward. He was there only a moment.

"Go in peace. We'll see you again," he said into the open air, and then turned away. From picking up her body to her burial, the process of burying Delecia was less than four hours.

Korvayan was not done. He took Rogers aside, pointed to the grave, and gave him a task.

"You see this. There was no burning," he said. "We did our job. You will get the message to all the people."

Education Resource

Meet the Journalists: Cheryl Hatch and Brian Castner

Pulitzer Center grantees Brian Castner and Cheryl Hatch discuss their project: The 101st Airborne...