Our Rainforest Journalism Fund website is available in English, Spanish, bahasa Indonesia, French, and Portuguese.

Sut Mai* started mining gold from the bank of Kachin State’s Mali River in 2013, when he was 18. He uses a shovel, generator-powered suction pipes, a sluice pan and a tray. “Local people have been mining gold for a long time, but it’s difficult and there’s not much profit,” he said.

He hails from Tang Hpre village in Myitkyina Township, just west of where the Mali and N’Mai rivers merge to form Myanmar’s longest waterway, the Ayeyarwady.

The confluence, known as Myitsone in Burmese and Mali N’Mai Zup in Kachin, captured global attention in 2011 when then-President U Thein Sein suspended a controversial US$3.6 billion hydropower project at the site. Launched two years earlier, the proposed Myitsone dam, a joint venture between China’s State Power Investment Corporation and Myanmar’s Asia World conglomerate, was expected to flood an area bigger than Singapore and displace more than 10,000 people.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Thein Sein took the landmark decision in the face of an escalating protest movement that united people across ethnic and political differences. Although the dam was never built, months before its suspension military authorities forcibly relocated some residents, including those from Tang Hpre, to new settlements with homes made of cheap materials and where the land was unsuitable for farming. In the years since, there have been some efforts to restart the hydropower project, but these have been met with protests.

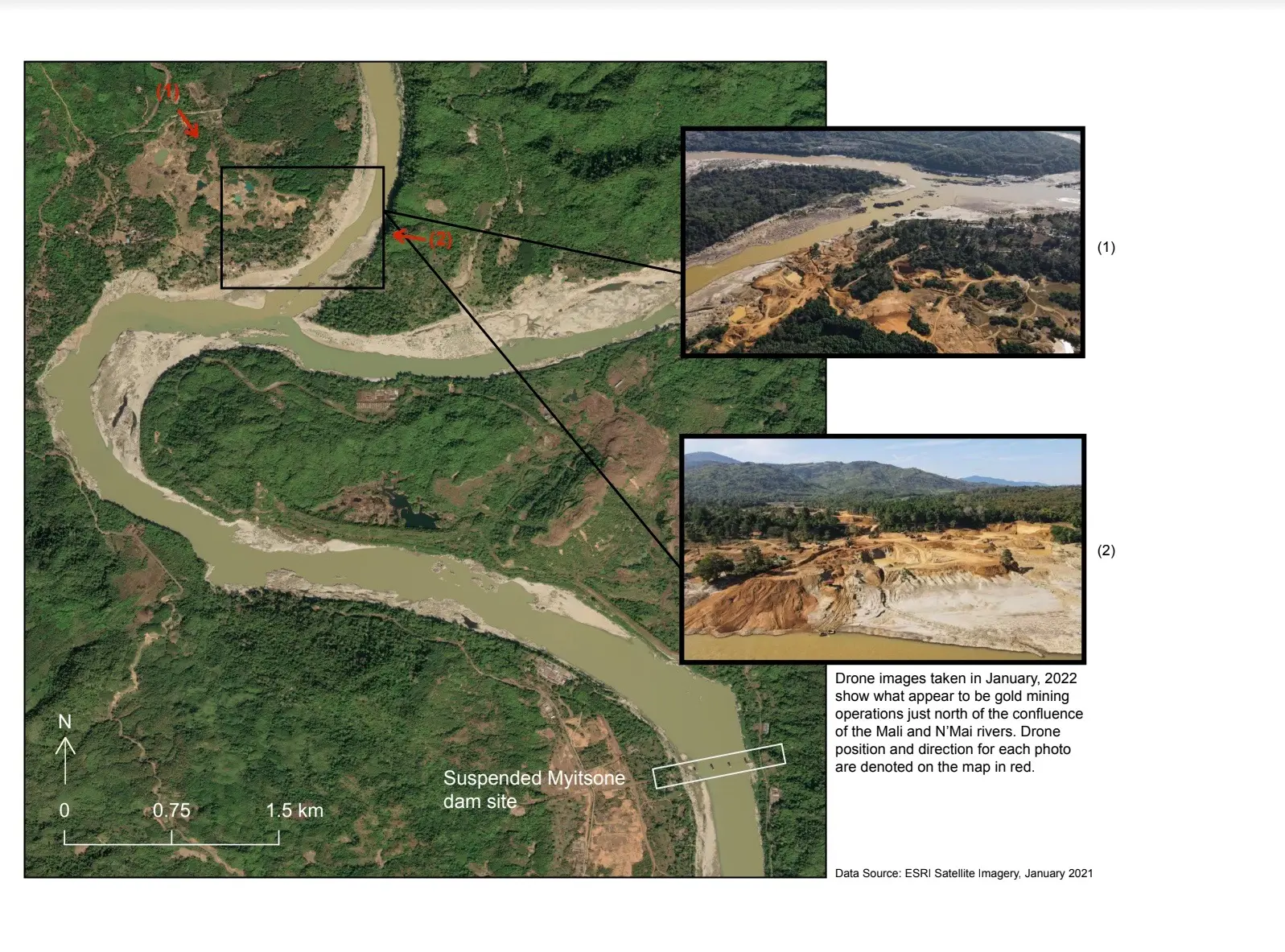

Since the military seized power in February 2021, however, Myitsone and the people from Tang Hpre have been facing another major threat: intensive gold mining. Activists, civil society workers and local people told Frontier that the main company behind the mining is Jadeland, which is owned by Kachin tycoon Sutdu Yup Zau Hkawng. They accuse the firm of digging with heavy machinery in areas beyond its permits, damaging the environment and displacing local people.

Unlike the Myitsone dam, however, there has been little pushback to the gold mining. Influential Kachin figures and institutions have not only largely remained silent, in some cases they have tried to shift the blame or even defended Yup Zau Hkawng and Jadeland, according to residents and activists, who would only speak anonymously for fear of retaliation from Jadeland or its supporters.

“The more we local people talk about it, the more we suffer, the more we lose. There is no one to stand with us,” said Brang Li*, who claims Jadeland is digging on his land without his consent. “We want someone or some group to stand with us to talk with [Jadeland], to get back our land.”

‘Everything we did … was just a waste’

People have mined for gold in Kachin for generations, but it tended to be small-scale and relatively sustainable. “Our ancestors didn’t mine to the point of destroying rivers,” said Ningrang Yuma*, a Kachin environmental activist.

That all changed in 1994, when the military regime known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council signed a bilateral ceasefire with the Kachin Independence Organisation/Army, the main ethnic armed group in the state. “The heavy machinery came in immediately after the ceasefire,” said Ningrang Yuma.

A 2004 report by Images Asia and the Pan Kachin Development Society describes a “devastating gold rush” in Kachin State, in which companies dug with disregard for the environmental or social costs along waterways and on land.

Local activists and civil society workers told Frontier that the National League for Democracy government (NLD), which came to power in 2016, made some efforts to regulate extractive industries in Kachin State, including gold mining, but that destructive practices continued through its term.

The coup, however, has erased even the limited progress made under the NLD, and created an opening for companies and individuals to mine with impunity, the activists and civil society representatives said.

“Everything we did during the democratic government was just a waste,” said Henry Awng*, a civil society worker, who served on a Kachin State monitoring group established under the global Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative during the NLD’s term. The EITI Board suspended Myanmar’s membership in the weeks after the coup and formal monitoring activities have stopped, Henry Awng said.

As a result, some companies are “mining gold as they wish” and in some cases pressuring locals not to speak out. Meanwhile, a deteriorating economy means many ordinary people are turning to gold mining to make a living, according to Henry Awng.

In recent months, local media reports have emerged of environmentally damaging gold mining practices in Waingmaw, Hpakant, Machanbaw, Putao, Sumprabum, Shwegu and Bhamo townships, as well as other parts of Myitkyina Township, in addition to Myitsone.

“Gold mining in the Myitsone area is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of environmental and social conflict in Kachin State,” a civil society member of an environmental monitoring group said.

‘Opportunists took advantage’

Jadeland is not the only company that has attracted negative attention for its gold mining practices in Kachin State — it’s not even the only one operating near Myitsone. In January, local media outlets reported that residents of the Myitsone area had also complained about other gold mining taking place on land businesspeople had bought under the guise of digging fishing ponds.

But the controversy around Jadeland has been particularly heated due to Yup Zau Hkawng’s high public profile and the disagreements between Jadeland and locals. Some told Frontier that they believe Jadeland is running the largest and most intensive gold mining operation at Myitsone, but that it is difficult to get detailed information because the mining sites are heavily guarded.

“After this issue became so hot and spread in the media, [Jadeland] stopped allowing local people to go near [its sites] and hired a lot of guards,” said a spokesperson from Mungchying Rawt Jat, a civil society organisation that focuses on the environment and land rights in Kachin. She expressed concern that an area which activists have fought to protect for more than a decade was now being destroyed.

“The N’Mai Hka and Mali Hka confluence is a significant place for all Kachin people,” she said. “Local people stood against the Myitsone Dam … That’s why this confluence is still surviving, still flowing. But when the political situation became unstable, opportunists took advantage to mine gold near Myitsone.”

Jadeland is also pushing out people who mine gold by hand and with small machines, residents and activists told Frontier. Sut Mai, the local gold miner, said that because of Jadeland’s operations he has fewer places to dig, and that the company’s activities “impact the livelihoods of local gold miners”.

There is a legal basis for Jadeland’s presence near Myitsone: In 2020, the Kachin State Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation issued Jadeland a permit to mine for gold at a four-acre site in Tang Hpre for five years. But civil society workers told Frontier that the company is mining beyond the allocated area, which is several kilometres from the confluence, and that its machines are visible within a few hundred metres of the riverbank, which they worry could cause erosion and flooding during the rainy season.

Local people also told Frontier that some landowners are being coerced into selling their property to Jadeland. Brang Li said Yup Zau Hkawng came to his land in Tang Hpre in October to negotiate a purchase price even though the company had already started digging on his property one month earlier. “They dig with backhoe machines without my permission. We can’t do anything about it,” he said.

Brang Li has refused to sell, but he said that others eventually gave in. “We feel devastated about it. What heritage should we give to the next generation? How should we resist it? Our village is going to be destroyed,” he said.

He and other locals said Jadeland’s gold mining sites are heavily guarded. “They have around eight watchtowers … If anyone comes close to their mining areas, security guards blow their whistles and stop them,” he said.

“Locals aren’t even allowed to pass through to reach their farms,” added Sut Mai.

Frontier received reports that one local person who had spoken out against Jadeland’s gold mining operations near Myitsone was beaten at knife point by a group of people who approached them in a vehicle. Frontier could not independently verify this incident and is withholding further details to reduce risks of retaliation for the victim.

Jadeland’s influential owner

Yup Zau Hkawng has near-legendary status for many Kachin people, thanks largely to his rags-to-riches story, and because he is a well-known benefactor to Kachin cultural causes, including traditional Manau festivals. He also chaired the Kachin National Association of Tradition and Culture from 1998-2008.

He is not without controversy, however. In 2009, a United States embassy cable described him as “the richest man in Kachin State”, largely due to his connections with the previous military regime and the KIO, and recommended targeted sanctions against him, his family and his companies.

The cable said Yup Zau Hkawng gained concession rights to about 10 jade mines in Kachin State’s Hpakant — home to the world’s largest and most lucrative jade mines — for his “instrumental” role in brokering the 1994 ceasefire between the KIO and the military, and also described his large concessions in logging, fishing and biofuel production.

Although his current levels of wealth are unknown, nearly 13 years later, he remains well-connected. He is one of three official members of the Peace-talk Creation Group, which has been mediating disputes between the military and KIO since conflict resumed in 2011. Myanmar Peace Monitor describes it as a group of “prominent businessmen who have vested interests in industrial or resource extraction.”

Yup Zau Hkawng’s second son, Mr Yup Sin Gawng Naw Htoi, is also married to the daughter of the junta-appointed Kachin State Chief Minister Hkyet Hting Nan.

Frontier’s calls to Yup Zau Hkawng either went unanswered or encountered a busy signal. Jadeland said a spokesperson would call back, but never followed up, and when Frontier tried calling again, the line was busy. Yup Sin Gawng Naw Htoi, who locals say is leading Jadeland’s operations near Myitsone, responded to a message over Signal, but requested that Frontier send questions by email, which he did not reply to.

A failure to mediate

Yup Zau Hkawng’s many connections make him a difficult man to defy. After gold mining began at Myitsone following the coup, locals appealed first to the KIO, writing to its headquarters and district office in July and August 2021 and asking it to order the suspension of gold mining with heavy machinery in the area.

While Myitsone is under the administrative control of the State Administration Council, as the military regime calls itself, two of the letter’s signatories told Frontier they trusted the KIO more to handle the issue.

“Even if the SAC allowed [companies] to mine for gold, if the KIO didn’t, no one would dare,” one of the signatories said. Another said a letter sent straight to the SAC would have shown disrespect to the KIO.

Colonel Naw Bu, of the KIO’s information department, told Frontier on January 5 that he was aware of the letter, but had not seen it and could not comment on it.

On October 5, the Kachin National Consultative Assembly organised a meeting with some of the letter’s signatories in the state capital of Myitkyina, about a 45-minute drive south of Tang Hpre. Known as WMR for its name in Jinghpaw, the assembly mediates social and political disagreements in Kachin State.

Zau Htoi*, a local resident who attended the meeting, said that WMR representatives “spoke in favour of Yup Zau Hkawng” and promised he would rehabilitate the land after mining. “They said that after Yup Zau Hkawng digs gold there, he will refill the mining pit, and then grow trees and build [retaining] walls on the riverbank,” he said.

Zau Htoi also said that during the meeting, WMR pressured him and the other residents to sign an agreement allowing Yup Zau Hkawng to continue his gold mining operations near Myitsone. “WMR said, ‘You came here as representatives of local villagers. Villagers will listen to your voices. You should sign to end this issue now,’” he recalled. “They pushed us so much and with many tricks to get us to agree to Yup Zau Hkawng's gold mining.”

Still, he and the other local people present refused to sign anything, Zau Htoi said.

A WMR spokesperson, who did not attend the meeting and spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that five WMR representatives attended the October 5 meeting. This included Reverend Hkalam Samson, interim chair of WMR and an influential figure in Kachin society. He also serves as president of the Kachin Baptist Convention, which represents the largest denomination among the predominantly Christian Kachin.

Hkalam Samson was seen in December 2021 with Yup Zau Hkawng at the inauguration of a Kachin Baptist Convention church in Nawng Pung, Myitkyina Township. Yup Zau Hkawng had donated funds toward the church’s construction in 2018, and his name is engraved on a placard in front of the church.

Hkalam Samson declined to be interviewed for this article.

Also present at the WMR meeting was Lamai Gum Ja, who serves with Yup Zau Hkawng on the Peace-talk Creation Group. When Frontier called Lamai Gum Ja, he repeatedly said he was busy and then stopped answering his phone.

The WMR spokesperson said that WMR and the PCG “acted as mediators” to “solve the issue through dialogue” with Myitsone residents, and that Yup Zau Hkawng later joined the meeting at WMR’s request after the issue could not initially be resolved.

The WMR spokesperson denied that WMR had put any pressure on local villagers during the meeting. “We just tried to discuss the issue to have mutual understanding between both sides,” he told Frontier. “Both parties must understand the root cause of the problem and not blame one another. This issue should be dealt with by collective thinking and investigation.”

Some local people have wondered whether the KIO delegated WMR to respond to their complaint letters regarding gold mining at Myitsone. WMR’s spokesperson denied this to Frontier, and Colonel Naw Bu said he was not authorised to speak on this matter.

Following their unsuccessful appeal to the KIO, residents issued an open statement on October 18 objecting to the mining of gold with heavy machinery at Myitsone.

Three locals who have spoken out against Jadeland told Frontier they experienced more pressure and intimidation after the statement was released.

One said that WMR requested another meeting, but that locals refused to meet, because they felt that WMR was acting “like an agent for Yup Zau Hkawng”.

Regional officers from the KIO and its armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army, also visited Tang Hpre and asked those who wrote the statement to come forward, the same person told Frontier. Naw Bu told Frontier that the KIO’s central committee was not aware of the visit and he could not comment on it.

One resident also said they were also contacted by junta officials after the statement was released, but they declined to meet. “We already released a statement and it was not necessary to discuss it with them,” they said, adding they did not want to be seen as cooperating with the military regime.

A local person who has been outspoken about Jadeland also received a letter written in red and placed on their motorbike from the “Truth Patriotic Group”. The letter warned them to “stop spreading false information”, which the recipient told Frontier they felt was meant as a threat.

An ‘affront to the desire of our people’

Dr Hkalen Tu Hkawng, a Kachin Baptist Convention reverend who serves as the natural resource and environment minister for the National Unity Government, told Frontier that he could not comment about Jadeland’s gold mining near Myitsone. The NUG was appointed in April 2021 by the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw — a legislative body made up of members of Myanmar’s elected parliament ousted by the coup — to represent Myanmar as its interim government in defiance of the junta.

Hkalen Tu Hkawng said it is not the NUG’s responsibility to investigate or respond to local complaints about Jadeland. “It wouldn’t be appropriate for the union level to intervene at the state level. Therefore, I have informed KPICT to take charge of this issue,” he said.

The minister was referring to the Kachin Political Interim Coordination Team, which was established in March last year by domestic and diaspora Kachin organisations to represent Kachin political aspirations.

Mr Nsang Gum San, the KPICT spokesperson, said in an email on December 8 that the group was working in consultation with the CRPH to “lead efforts to govern the Kachin Region under the security umbrella of the KIO/A.”

He said KPICT was “looking in depth” at the scale of gold mining operations in Kachin State, but it was “challenging to implement mining standards and environmental law when the State is effectively unstable and no party is exercising full control of the territories.”

“We call upon all residents of our Region to exercise caution in mining arbitrarily anywhere they please simply because [the] coup regime permits,” he said. “We have to realize that our younger generations will never see our state’s bucolic countryside and pristine natural forest if we continue on this mining rampage.”

He said that KPICT had no direct contact with Yup Zau Hkawng or Jadeland, however, and emphasised that it was important to look at the bigger picture of gold mining across the state and to investigate “financiers and enablers” of gold mining projects.

“We cannot single out Yup Zau Hkawng for gold mining in Kachin,” he said.

However, in updated comments sent to Frontier hours before this article was published, Nsang Gum San said despite the fact that Jadeland’s permit was granted under the NLD, the KPICT “doesn’t permit or condone destruction of the confluence.”

“Jadeland and other operators who mine gold near Myitsone [are an] affront to the desire of our people and irreparable harm to the environment,” he said.

‘Protecting the environment is also revolutionising’

On December 27, 2021, the KIO issued a statement prohibiting gold mining in KIO-controlled areas. Naw Bu told Frontier that the KIO was unable to grant or withdraw permission to mine gold in areas outside of its administrative control, including near Myitsone.

“The KIO is against all kinds of activities that damage the environment or civilians’ land and property. However, we are not able to protect or maintain the environment in non-KIO controlled areas,” he said.

Despite claiming the KIO does not have control over gold mining at Myitsone, in a follow-up interview, Naw Bu confirmed that the KIO collects taxes from gold mining activities there, as it does from many projects across the state.

“Gold mining is related to all of us and our [Kachin] nation so we tax it,” he said, adding that collecting taxes is a “small job which is normally carried out by subordinates on the ground” and he did not know the specifics about taxes on mining at Myitsone.

Naw Bu also said the KIO was in a “difficult position” to establish gold mining regulations for a specific area and was instead drafting policies to regulate the industry throughout the state. But this was not an easy task while the group was in open conflict with the military regime, he said. “The most important thing right now is to finish this revolution as fast as we can.”

The KIO’s General Secretary Mr Kumhtat Hting Nan responded to questions about gold mining during a live video conference organised by the World Kachin Congress (WKC) on February 6. He said that after the coup, the military’s Northern Command reapproved existing gold mining permits at Myitsone which had been issued during the NLD’s term, as well as plans to transform Myitsone into a tourist destination and natural park.

When Frontier tried calling military-appointed Kachin State Chief Minister Hkyet Hting Nan (who has no relation to Kumhtat Hting Nan) the call encountered a busy signal.

During the video conference, Kumhtat Hting Nan acknowledged public concerns that gold mining could affect a place of historical and environmental significance, and negatively impact local people. “In the past, there was a plan to build a hydropower megadam, but together, we the people strongly opposed the project. Now, another issue is happening again in that area, so we are still wondering what other plans [the military regime] have for that area.”

According to Kumhtat Hting Nan, the KIO’s western central office in Myitkyina had ordered the suspension of all gold mining at Myitsone, but businesspeople were “refusing” to follow the order. He did not name any specific examples or mention when the order was issued.

“[Businesspeople’s] actions might be considered as ‘seeking out opportunity in times of crisis’, but we still need to observe closely whether their claim is true or whether they are cheating,” he said regarding the alleged plans to establish a natural park.

He said the KIO central committee is “still observing” the situation before deciding whether to give an order to stop all gold mining in the area.

Residents and activists told Frontier they would like to see the KIO unequivocally take action against gold mining at Myitsone.

“Currently, we don’t have a legitimate government, so we don’t have a platform for local people’s voices,” said the Mungchying Rawt Jat spokesperson. “That’s why we think only the KIO, which is protecting Kachin State and Kachin people, has a big responsibility for this issue. We believe in the KIO, and we want to request that they consider stopping gold mining as their biggest responsibility for the sake of Myitsone’s long term survival.”

“Even when the KIO wins the revolution, if the N’Mai and Mali rivers are destroyed, winning will be for nothing,” she added.

Zau Htoi agreed that the revolution for self-determination must go hand in hand with environmental protection. “If we get [self-determination] in Kachin State when there is nothing left, it is a waste. Protecting the environment is also revolutionising,” he said.

* denotes the use of a pseudonym.