He wakes up at five in the morning and washes away his deep-sea dreams, the hot water spilling off his balding crown, running down his goatee and his bulky paunch. Then he gets into his sand-colored cargos and shirt, puts on his gear, checks his M4, grabs his battered laptop loaded with PowerPoint presentations — "Evidence Scene Protection," "Counter-IED Training," "Riot Control" — and climbs into a Humvee or MRAP to go to the next police station or training outpost. When he arrives, he greets the Iraqi policemen. As-salamu alaykum, he says. Wa alaykum as-salam, they reply. Peace be upon you. Peace be upon you, as well. The right hand touches the left side of the body armor, where the heart is hiding. Peace be upon you. Never has a war been fought with so much kindness. "I dreamed I was scuba diving last night," Bill Connelly says over the intercom of the MRAP, a twenty-ton, six-wheel mine-resistant vehicle that looks like a submarine on wheels. It's the same conversation every day. Always diving.

"Yeah, I've been thinking about it a lot," Will Martin's voice comes in crackling. "As soon as I get out of this job, I'll get my license for master scuba-diver trainer and will open my own school. Somewhere in Costa Rica or Honduras."

Will Martin is Connelly's thinner twin: a goatee, a smaller paunch. Both of them worked as cops and are employees of DynCorp. War Pigs, they call themselves. Standing side by side, they vaguely resemble Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Except that Martin is quieter, more aloof. He has been in Iraq since almost the beginning of the war. The pupil of his left eye spills into the blue iris, like a broken egg yolk. He used to be roommates with Connelly in Kosovo, where they trained that country's fledgling police force. Now they're training this country's, at least for a few more months. Then their students will have to fend for themselves.

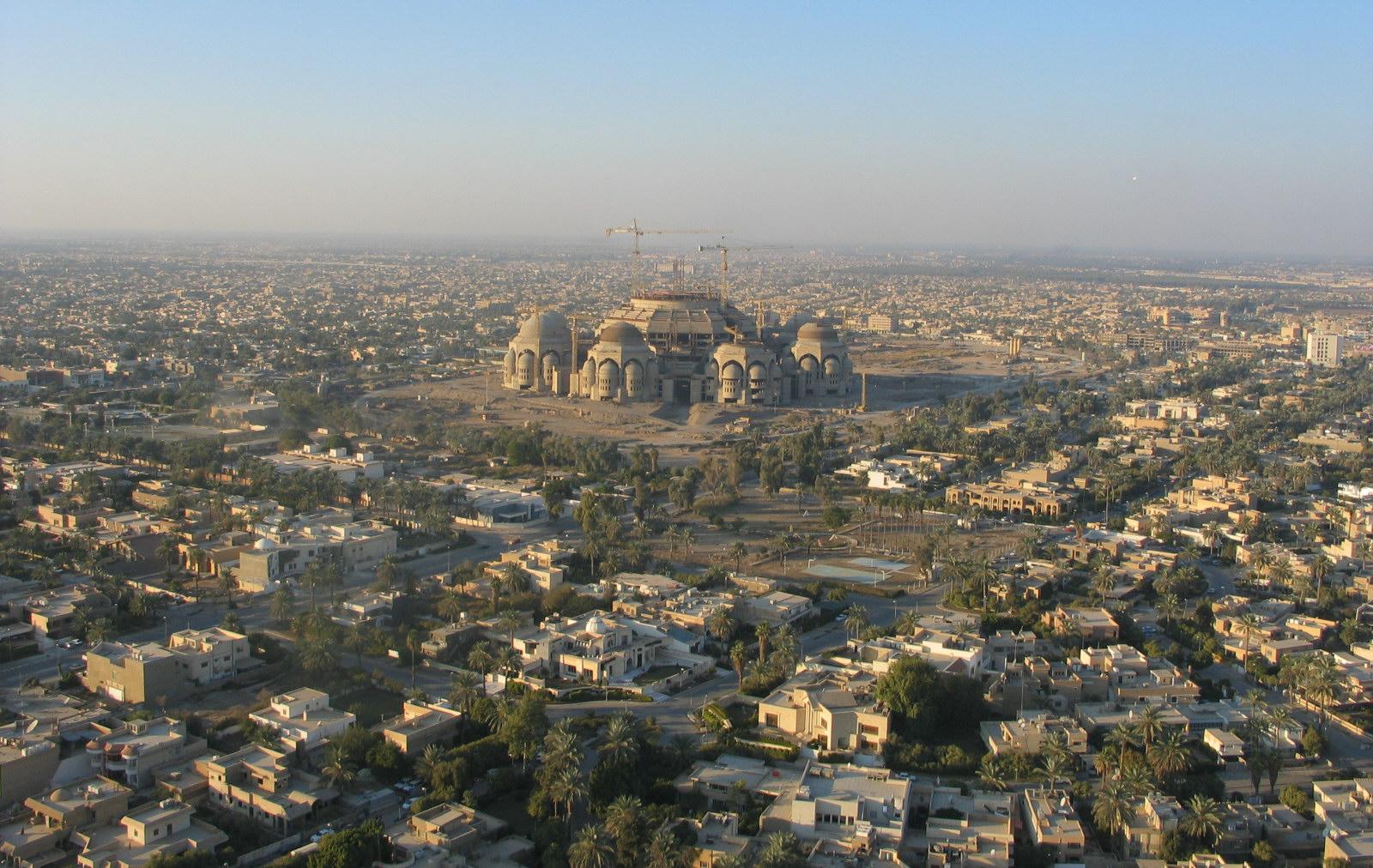

The armored convoy lurches forward, pushing through the gates of Camp Liberty, the sprawling U. S. base on the western outskirts of Baghdad, past Ugandan contractors with loaded Kalashnikovs and boonie hats slung low over their eyes. There are two beat-up Iraqi police trucks in the lead. Anytime Connelly* and Martin* or any MPs go beyond the wire, Iraqi escorts come along.

Outside, drab brown tenements and mud huts rise out of smoldering mounds of trash. A few cows graze in the refuse. In the distance, the four smokestacks of the local power plant shoot up like hypodermic needles, injecting the sky with their black smack. Only the palms, their fronds frozen in silent explosions, and Martin's stories — about diving, about binge drinking, about prostitutes in Thailand — add a bit of color.

"I think I'll buy a house here. It'll cost me cheap," Martin says. "You've got livestock as well," says Connelly.

There are four U. S. armored vehicles in the convoy holding twenty-four men: four noncommissioned officers from the 49th MP Brigade, which is overseeing much of the police training in Iraq; sixteen personal-security details from the 229th MP Company charged with protecting them; two linguists; and Bill Connelly and Will Martin, who will lead the training. The Gatorade and water in the cooler next to Connelly shake as the convoy starts and stops. Every so often it comes across an Iraqi police vehicle parked by the roadside or broken down. Several cops are having a picnic on the bed of their truck; another is standing by his motorcycle fingering his prayer beads, looking contentedly around. There is no reason to worry. Everything will be fine. Inshallah, God willing.

Suddenly the convoy comes to a halt.

"What happened?" somebody's worried voice.

Silence.

"One of the police escorts stopped to buy a doughnut," Specialist Brian Dexter, the turret gunner, reports.

Silence.

"Are you kidding me? Right now?" asks Sergeant John Paras, the truck commander. "Roger, sir."

"A doughnut?"

"Sorry. Cigarettes. He's buying cigarettes."

Silence. Then laughter. It's all good. At last the convoy snakes through a couple of concrete roadblocks and pulls into a parking lot of the Iraqi Patrol Police Headquarters, on the opposite side of the Tigris from the International Zone. To one side is the new American-built training center with an indoor firing range and a makeshift boxing ring. To the other are more than a hundred blown-up police cars stacked atop one another like piles of prehistoric bones. Next to the heaps of twisted metal and shattered glass, sitting on tattered scraps of cardboard in the parking lot, cross-legged and calm and potbellied like Buddhas, are the new Iraqi recruits.

As the crew members spill out of their vehicles, weapons on red, the students across the parking lot stare at an Iraqi instructor teaching them bomb-detection techniques. He clicks open a black briefcase and takes out a plastic hand grip with a swiveling antenna. With his arm relaxed at his side, he draws a deep breath, then slowly raises the device until the antenna is parallel to the ground. A small plastic bottle with C-4 has been placed a few feet away, and the antenna swivels on its own in the direction of the explosive.

The students, wearing tattered, mismatched uniforms, are wonder-struck. One by one they get up to give it a try. But most struggle to balance the antenna while walking, as if getting tested for alcohol. The antenna swings wildly left and right, detecting smiles and giggles instead. The device, which can cost up to $60,000, is called ADE 651. A few months ago a Cambridge University scientist concluded that the plastic cards within are nothing more than simple antitheft tags. The detector doesn't work, the American military told the Iraqis. But the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior had already spent $85 million to outfit the entire police force, so they continue to use it.

One of the cops approaches Connelly and the MPs, who are standing across from the training. "It works," he says with a smile, "but a lot of the guys prefer teasing their girlfriends with it, produce a big bang."

Connelly looks for a brief second at the young Iraqis testing the bomb detector in front of the blown-up cars. He's been in Iraq two years now. His job is to assist and advise, check off a box, and move on to the next mission. Beyond that, he is to offer no opinions, no unsolicited advice. So he does the only thing he can: He walks away. Soon he'll be gone, and securing the country will be left to the disheveled, laughing Buddhas and their magic wands...

Continue reading the full story at Esquire.

*These names have been changed because DynCorp has not authorized them to speak with the media.