A carbon project began selling credits hailing from the indigenous reservation of Cumbal, in the paramos of southern Colombia, despite the fact that most of its inhabitants weren’t even aware of its existence. At the head of the initiative that has caused tension in the community and whose documents are not public, is a Mexican company and its Colombian subsidiary, whose manager was a founder and shareholder of the company that audited its own project.

On December 7, 2022, Diana Puenguenan saw a message that alarmed her. A former governor of the Cumbal indigenous reservation, where she lives, had shared on his WhatsApp status a photo of a legal document announcing the closing of a carbon credit sale in that community. "Does anyone know about this?" he asked.

That was the first news this 25-year-old sociologist, public administrator and indigenous Pasto of 25 years had that an ambitious payment for an environmental services project was underway in her indigenous territory, nestled between the paramos (alpine tundras) and volcanoes in southern Colombia, on the border with Ecuador.

Her reservation, she began to understand, was home to a voluntary carbon market project. These deals link local communities that care for strategic forests to mitigate the global climate crisis with companies that buy their carbon credits to offset their own use of fossil fuels. Each credit generated by these so-called REDD+ projects is equivalent to one ton of carbon dioxide — one of the greenhouse gasses that drive climate change — that no longer goes up to the atmosphere as a result of that conservation effort.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

It was an interesting initiative for her region, which preserves some 49,000 hectares of paramos, a high-mountain ecosystem that only exists in a handful of tropical countries and is considered strategic because of its water richness. There was, however, a problem. Despite the fact that this type of initiative requires broad socialization and the participation of the entire community, she’d only found out about it when it was already a fact.

She wasn’t the only one left in the dark. In the days that followed, several colleagues who, like Diana, were Pasto Indians, university professionals and inhabitants of the Cumbal reservation, said they were equally perplexed. They formed a working group to investigate further which, in the following weeks and as they delved deeper into their findings, became the Cumbal Environmental Collective. For the past five months, they have tried without much success to obtain more information about the project. They wrote to their governor, the developer and the certifier. None have responded.

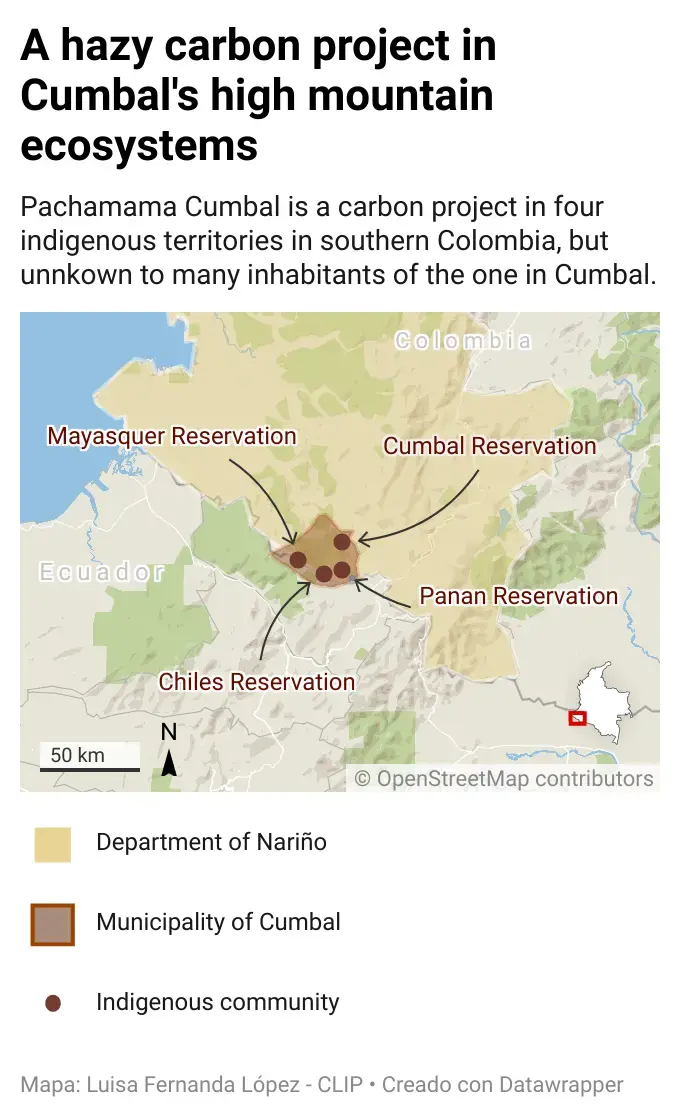

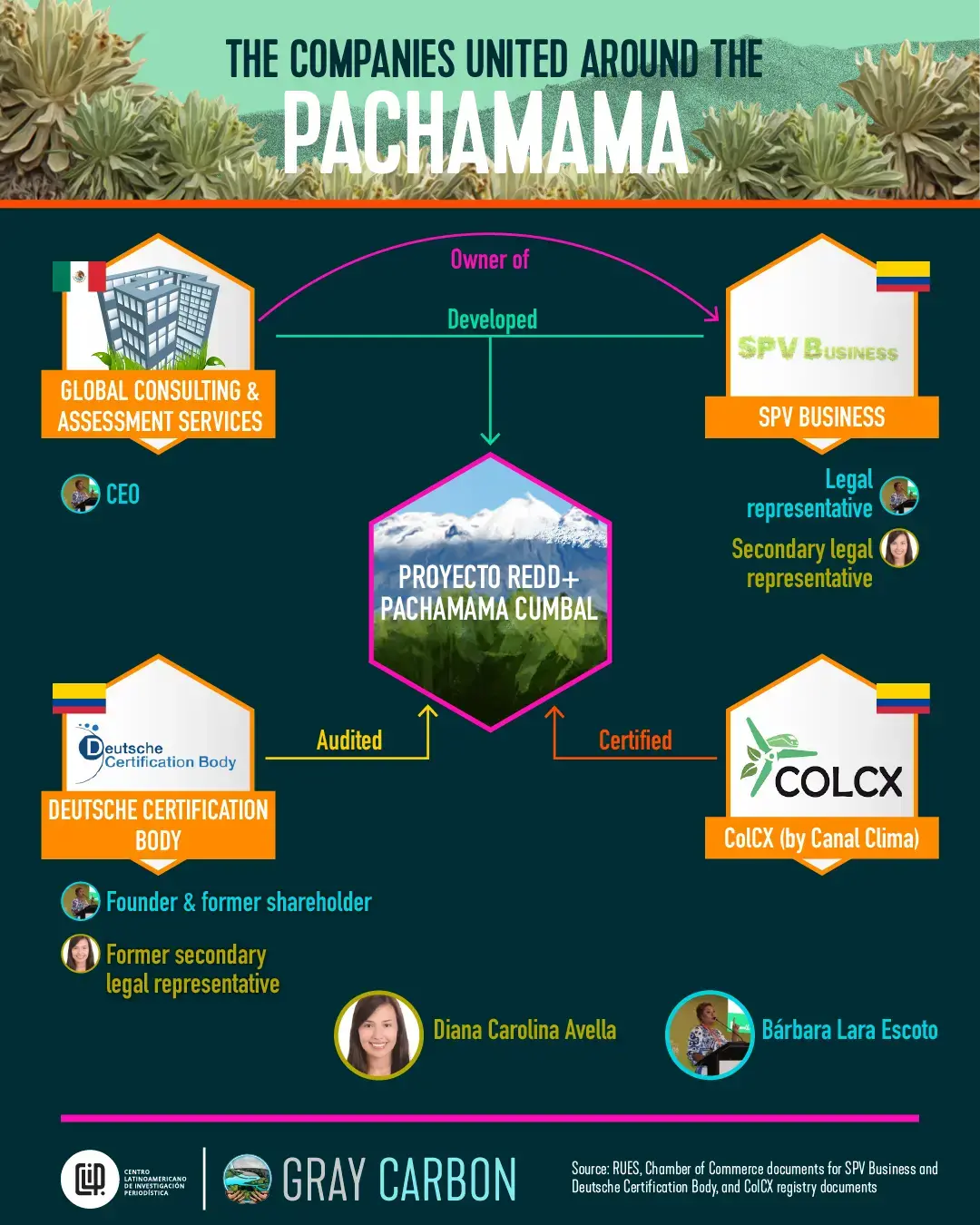

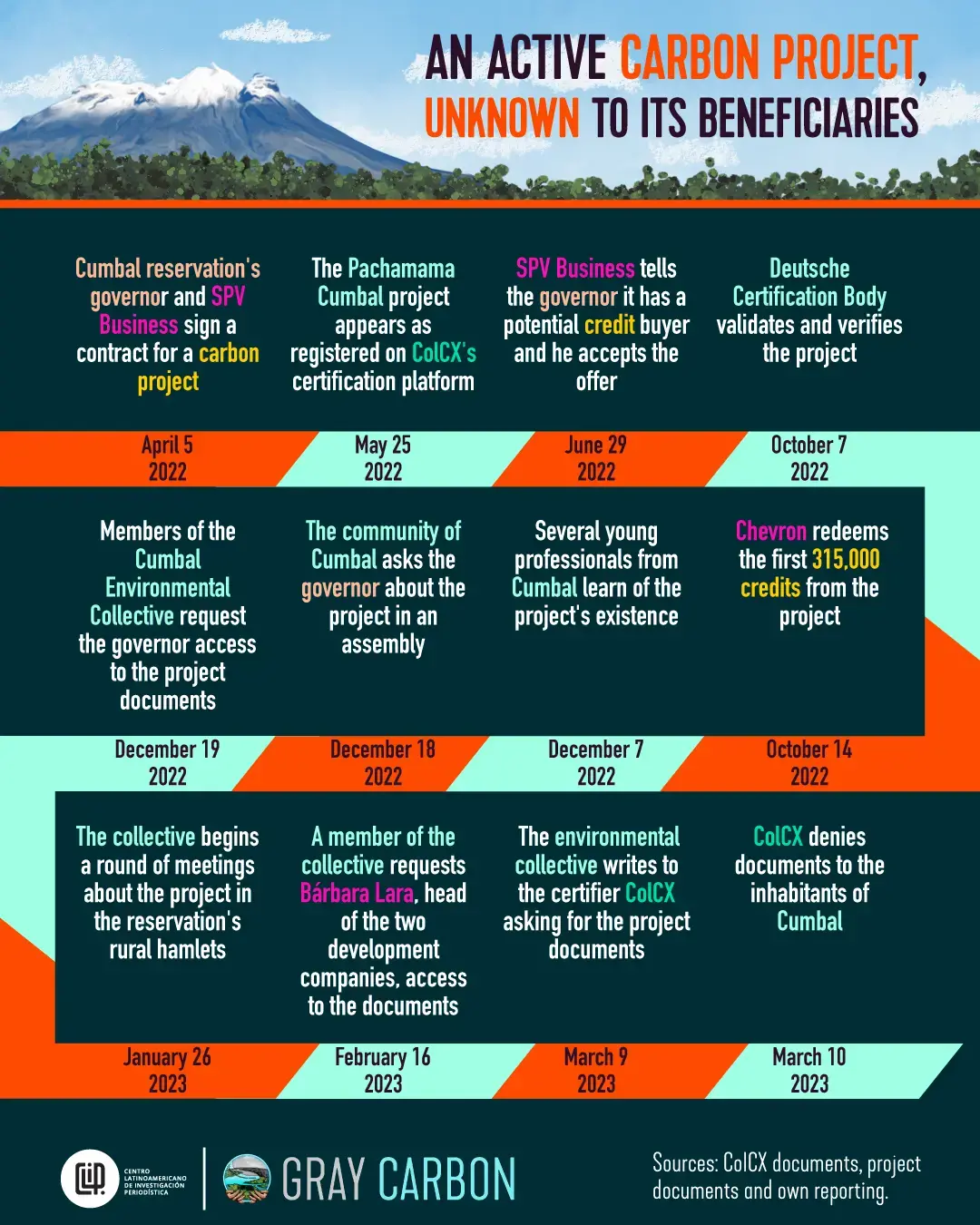

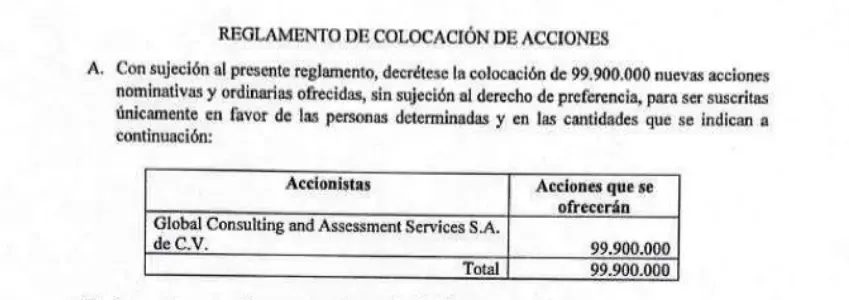

The project, however, was more advanced than they knew. Promoted by the Mexican company Global Consulting and Assessment Services S.A. de C.V. and its Colombian subsidiary SPV Business S.A.S., the Redd+ Environmental Project for the Protection of Pachamama Cumbal has been registered on the platform of the Colombian certification standard ColCX since May 25, 2022. In addition to theirs, it brings together three other neighboring indigenous reservations and draws its name from the Inca word for "mother of the world."

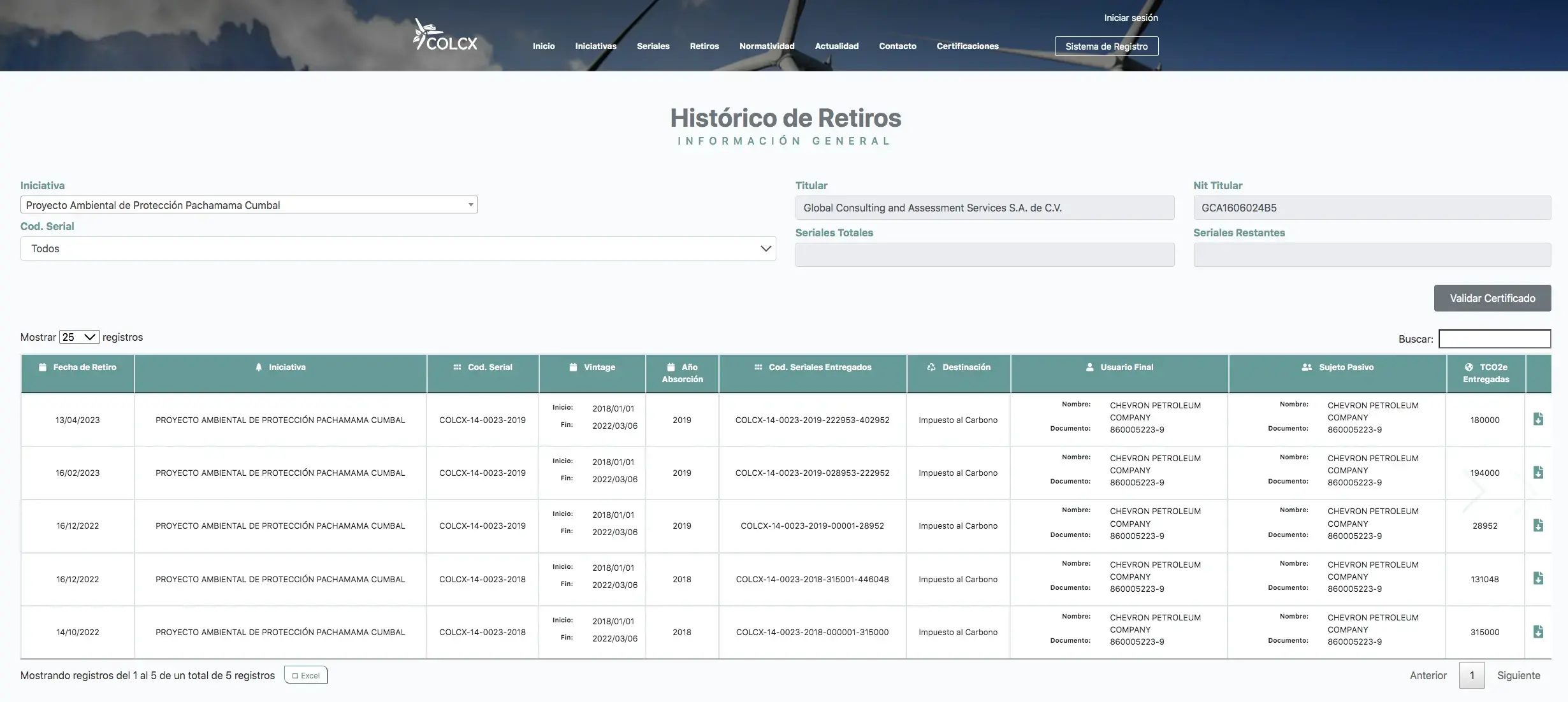

Five months later, on October 14, the first batch of 315,000 Pachamama project credits was redeemed by the oil company Chevron, according to the certifier ColCX’s registry. In other words, a company claimed the conservation results of the Cumbal reservation eight weeks before many of its inhabitants were even aware of the project's existence.

The case of Diana Puenguenan’s volcanic reservation is illustrative of a broader problem: Despite their potential to bring invaluable resources to those who care for "mother earth," many Redd+ projects in Colombia are being socialized with only a fraction of their communities, are not transparent or accountable to the majority of their beneficiaries, and are fostering social fractures. Cumbal seems to be an extreme case: Until today, its inhabitants knew almost nothing about the project housed in their collective territory and that has already closed five transactions totaling almost one million credits.

This isn’t the only singularity about the project. The company that audited it and gave it the go-ahead to sell carbon credits, Deutsche Certification Body S.A.S., was co-founded by Bárbara Lara Escoto, who is CEO of one of the two companies promoting the Pachamama project and legal representative of the other, according to Chamber of Commerce records for the two Colombian companies. Her alternate legal representative at Colombian subsidiary SPV Business, Diana Carolina Avella Ostos, was also a legal representative for the same auditing company until a month before signing the contract with the then governor of Cumbal, according to the company's records. This dual role shows that those who were supposed to independently assess the project in the forests and paramos of Cumbal might not have such independence.

These are some of the findings of an investigation by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), in partnership with Mongabay Latam, La Silla Vacía and El País América, and with support from the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network. This collaboration is part of Gray Carbon, a journalistic series that has been shedding light on how the carbon market is working in Latin America.

A nebulous project in the mountains

Since the Cumbal Environmental Collective’s members learned of the Pachamama project in early December, they have been gathering information bit by bit.

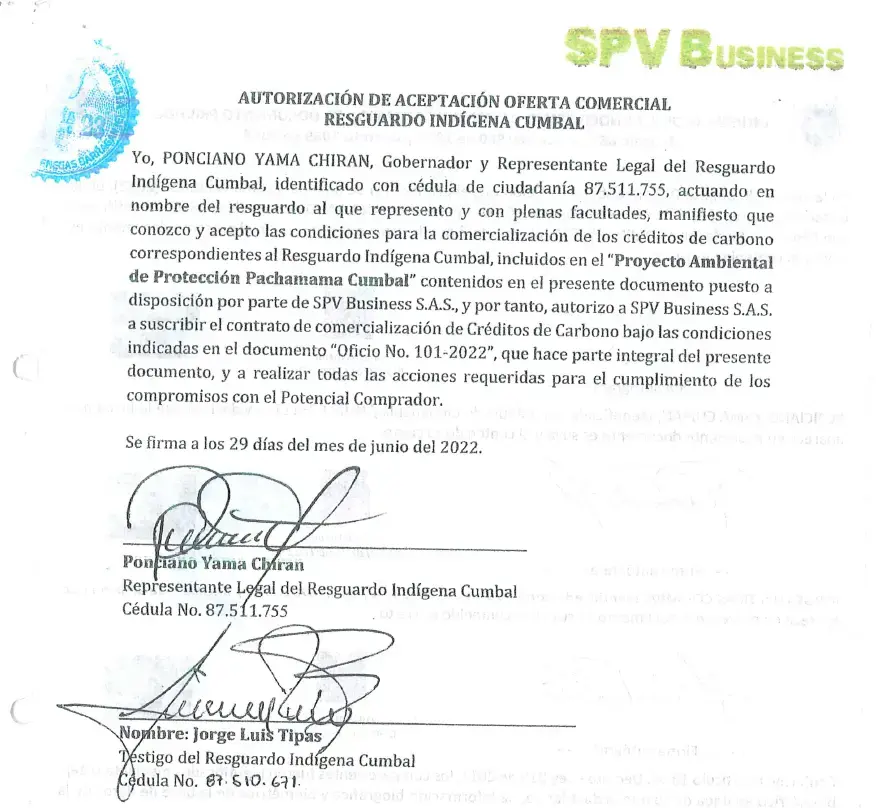

On December 10, 2022, three days after Diana sounded the alarm, her colleague Miguel Ángel Quilismal managed to obtain the first document. It was a letter, dated June 29, 2022, and with notary stamps, in which the company SPV Business informed Governor Ponciano Yamá Chiran — different from the one who had alerted of the offer in his WhatsApp status — that it had a "potential buyer," whom it did not identify, interested in acquiring all the credits issued by the reservation between January 2018 and mid-2022. The same pdf included a second, more succinct letter, in which the then governor accepted the commercial offer that same day. That was the document they had seen on the former governor's WhatsApp status.

Those two letters gave them a better understanding of the dimensions of the project: it covered not only their territory but also the neighboring Pasto reservations of Chiles, Panán and Mayasquer, which are part of the same municipality and the same paramo complex. According to the document, Cumbal was entitled to a little less than half of the 1.6 million bonds sold, as it’s the largest territory.

The news spread like fog through this dairy-producing town at 3,000 meters above sea level. A week later, during the December 18 town hall meeting in which Governor Yamá was to give an account of his administration, questions about the Pachamama project rained down on him. The community demanded that he explain the agreement and make the documents public. "He was never clear nor did he explain how the process began. He only talked about the needs of the reservation and how money transfers [from the Colombian state] are not enough to cover them," says Diana Puenguenan. She also recalls that, in response, they were accused of opposing development and investment in the community’s well being.

This second document turned out to be the contract signed on April 5, 2022, by the then governor Ponciano Yamá with the company SPV Business to "create a Redd+-type emissions reduction project derived from avoidance of deforestation and forest degradation, to be implemented in the entire extension of the territory of the Gran Cumbal Reservation." The legal document, notarized in Bogotá, describes some of the terms of the agreement: It will last 30 years — extendable up to a century — and its income will be divided among the promoters, with 60% corresponding to the four indigenous reserves and 40% to the developer.

With the turn of the year came a new governor, but little details about the nebulous carbon project or how the money it brought in has been invested. Faced with the repeated lack of answers, since the end of January and for two months, the members of the environmental group organized informative meetings in eight of the nine rural hamlets that make up the reservation. "We realized that in none of them it had been socialized," says John Fredy Alpala, a 31-year-old environmental and sanitary engineer and another of the collective’s founders.

Neither the previous governor Ponciano Yamá — who signed the contract — nor his successor Héctor Villacriz —who is executing it — responded to interview requests from this journalistic alliance about the project and how the resources stemming from it are being invested.

Carbon among moorlands and volcanoes

Global Consulting and SPV Business are two of the newest players in Colombia's growing carbon market.

In the last six years, more than a hundred private projects of this type have appeared throughout the country. These schemes were incorporated into the United Nations Climate Change Convention to connect national governments that are curbing deforestation with others that want to pay for those results, but Colombia decided to expand them to include private projects from the voluntary carbon market as well. Redd+ projects have since blossomed in Colombia's Amazon and Pacific rainforests, but also among Caribbean mangroves, Orinoquia's savannas and Andean paramos like these in southern Nariño.

There are three reasons for this boom. The first is that in 2017 the Colombian government created a tax incentive that allows companies that use fossil fuels to reduce or not pay the carbon tax if they buy these credits. The second is that a large part of Colombia's jungles and forests — totaling 600,000 square kilometers, or the area of Ukraine — is guarded by indigenous and Afro-descendant communities that usually have collective ownership and effective governance of their territories, which is why many companies began to seek them out to promote private carbon projects. There is an additional one: the possibility of turning a quick profit, without much technical, social and environmental supervision by the state.

Although paramos contain far fewer trees than a rainforest or a forest, they are fundamental ecosystems in the fight against climate change for another reason. Their organic-rich soils retain high amounts of carbon, which is released into the atmosphere if the topsoil is removed. For this reason, carbon market projects in paramos seek to discourage drastic changes in the use of these fragile soils, especially their burning and reconversion for agriculture or livestock, which could take hundreds of years to reverse.

In theory, all projects must comply with global principles that seek to ensure that initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation or forest degradation work well and actually protect local communities and biodiversity. One of those social and environmental safeguards — which Colombia turned into a list of 15 detailed ground rules — is that interested communities have clear and easily accessible information about the initiatives.

In Cumbal, that situation didn’t improve even when they spoke to the company in charge of the project. In mid-February, collective member and engineer Alpala managed to get into a meeting between Global Consulting and SPV and leaders of the reservation, in which — at his request — CEO Bárbara Lara Escoto promised to share with them a drive with all the documents of the Pachamama project. Three months later, Alpala says he’s had no news of this drive.

Above all, there are two foundational documents for any Redd+ project that Alpala and the other members of the collective have not yet been able to consult: the project design document (or PDD, in industry jargon) and the report of the external auditor who assessed it. These are usually available on Renare, the Colombian government platform that lists all mitigation initiatives, but which has been out of service since last August. Nor are they published on the platform of the certifier that awarded its seal of quality to the project.

As none of the governors have responded and Global Consulting’s Bárbara Lara has not fulfilled her promise to make them public, on March 9 they wrote from the environmental collective's email to the Colombian certifier ColCX, one of four operating in the country. After introducing themselves as "part of the community of the Gran Cumbal indigenous reservation," they asked to share both documents, explaining that the governor has not done so and arguing that reading them is the community's right. "The non-delivery of this information has generated division and social conflict among the community, since it doesn’t know about the formulation, execution, indicators or goals to be developed in the project," they wrote.

ColCX — whose parent company Canal Clima is part of Valorem, the holding company of the Santo Domingo family, one of the richest and most powerful in the country — responded the following day. It did so by denying them access to the reports. "Following due process, it should be requested to the owners and/or the governor," its technical manager Catalina Fandiño tersely said. She omitted that, precisely, the problem has been that neither the incumbent companies nor the governor provide them any answer.

Since January, this journalistic alliance asked ColCX for access to the project documents, given that — unlike its competitors, the U.S.-based Verra and the Colombian Cercarbono and BioCarbon Registry (formerly ProClima) — this certifier does not make them public in its project registry. In a first response in January, Fandiño said that "the design document for each of the projects is confidential and property of the community and/or developer," but that she would request them from the developer. Upon further requests, in March she responded that "we did not obtain approval to share the requested information."

In an interview on May 30, ColCX explained that it trusts the thoroughness of the documents submitted by developers and auditors, but that it cannot share them because its contracts with developers — including Global Consulting — include confidentiality clauses. "We are unfortunately contractually bound and the only one who can authorize us is the developer," said its director Mario Cuasquen, adding that they were not aware of the conflict in the community as a result of the carbon project but that as certifiers they cannot play any role in its implementation.

Cuasquen, however, acknowledged that there is a difference in the standard of transparency with its competitors and that this episode generated self-criticism within ColCX. "We realized that, due to an administrative issue, maybe that aspect was left behind [insufficient] and that this wasn’t the best practice," Cuasquen said. One of the decisions they made as a result of a consultancy they hired, he said, was to eliminate the confidentiality clause in contracts from now on, so that all new projects will make their documents public. In projects already in force, such as Pachamama, this will be done gradually as they renew their contracts with ColCX.

On May 14, the Cumbal environmental collective wrote again to Global Consulting and SPV, insisting on their right to consult these documents. Again, there was only silence.

The promoters of Pachamama

The owners of the Pachamama project referred to by the certifier ColCX are, in addition to the governors of the four reservations, two companies linked to each other. One of them, the Colombia-based SPV Business, signed the contract with the Cumbal reservation, while the other, the Mexico-based Global Consulting and Assessment Services, was the one promoting the initiative before the certification and auditing bodies.

SPV Business, created in Bogota in September 2020, lists Global Consulting and Assessment Services — represented by Yolanda Escoto Torales — as the sole shareholder since August 2022, according to Chamber of Commerce documents. In turn, Global Consulting is a company that has its address in the Mexican city of Queretaro.

The head of both development companies is Bárbara Lara Escoto, a Mexican chemical and industrial engineer who worked for Norwegian audit firm Det Norske Veritas. Since 2008 she is the founder and manager of Global Consulting, a company that — according to her own description — has helped register "more than 1650 projects from different productive sectors before internationally recognized carbon standards." She is also, since March 2021, the legal representative of SPV Business. In Colombia she was invited by the oil palm industry group Fedepalma to its international congress last September, where she spoke about carbon credits as "a possibility to generate additional income in the palm agroindustry."

This journalistic alliance requested interviews with Global Consulting’s Bárbara Lara and SPV Business’s Diana Carolina Avella since May 20, both by email and telephone. Neither of them responded.

A not so independent auditor

In the carbon market, Redd+ projects are submitted by developers to a certification standard such as ColCX. In order for the latter to give it its seal of approval and allow it to issue credits, it assesses reports in which an external auditor validates the project and verifies the deforestation it has avoided. The work of this auditor, who is usually paid by the developer, must remain "impartial to the activity being validated or verified, and free from bias and conflict of interest," according to one of the international standards that regulates their work and that is in force in Colombia.

However, in Pachamama’s case, this distance between developers and auditor is less clear. In what could constitute a conflict of interest, the Global Consulting’s manager and SPV’s legal representative was also a shareholder of the auditor that validated it in October 2022 and verified its removal of 2.6 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) that allowed it to sell the same number of credit.

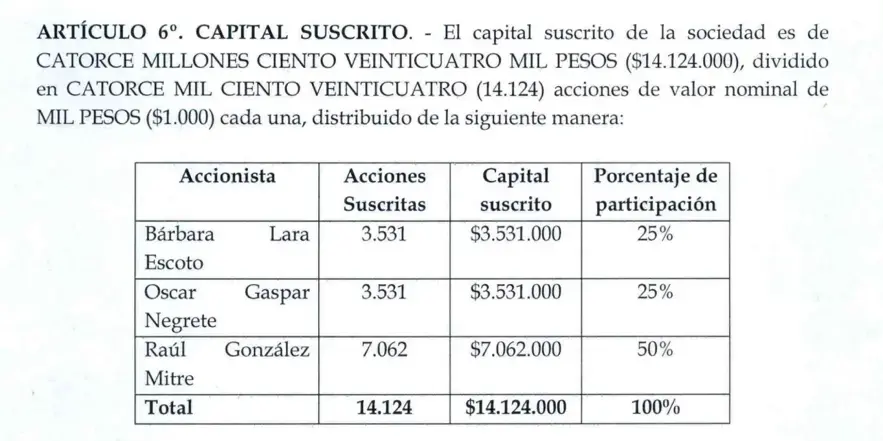

Bárbara Lara Escoto, CEO of Global Consulting and legal representative of SPV Business, is listed in Chamber of Commerce documents as founding partner of Deutsche Certification Body S.A.S. Created in June 2019 to provide "testing, inspection, supervision, certification, research and evaluation" services in "greenhouse gas emission reduction, mitigation, capture, sequestration and storage projects," the Bogota-based auditing firm had three founding partners, all of them Mexican nationals: Raúl González Mitre had half of the shares, while Óscar Gaspar Negrete and Lara Escoto had a quarter.

Lara was listed as a shareholder of Deutsche Certification Body until at least March 2021, according to Chamber of Commerce documents. One year later, in March 2022, her former business partner Óscar Gaspar was listed as the sole shareholder of the audit firm. It was precisely he who signed the validation and verification statements for the Pachamama Cumbal project in October 2022, which appear on ColCX’s platform, as president and legal representative of Deutsche Certification Body.

This is not the only link between developers and auditors. Diana Carolina Avella Ostos, who has been listed since March 2021 until today as SPV Business’s alternate legal representative, held the same position in Deutsche Certification Body between March 2021 and March 2022, according to the auditor's Chamber of Commerce records. Avella Ostos, a chemical engineer who worked at Fedepalma, was the person who signed the contract with the governor of Cumbal in April 2022 and the commercial offer to purchase the credits in June 2022.

Since the full audit reports are not public and ColCX denied access to them, this journalistic alliance could not verify whether these business and personal connections were made public.

This journalistic alliance sought out the three companies involved in the audit process to hear their views on these relationships and to understand how they handle potential conflicts of interest. Like Global Consulting and SPV Business, Deutsche Certification Body did not respond to an interview request made by email on May 20.

Certifier ColCX told this journalistic alliance that it wasn’t aware of such links. "I hadn’t heard. It is a matter of alarm and the issue of conflict of interest would have to be assessed," said its technical manager Catalina Fandiño, adding that the procedure would be to report the facts to Colombia's National Accreditation Body (ONAC), which oversees auditors in the country. ColCX director Mario Cuasquen explained that the company and the Valorem group have a rigorous due diligence process of their suppliers, that they verify that the auditors are accredited with ONAC and that they rely on the oversight from this mixed entity, but acknowledged that they don’t review corporate documents in detail. He also admitted that ColCX does not currently have a conflict of interest assessment procedure, but that in the update it is making to its protocol it will include an obligation for developers to declare possible conflicts of interest. "Our goal is to remedy the weaknesses that the standard may have, in a process of continuous improvement," Cuasquen said.

The oil client

In its six months of life, Cumbal's Redd+ project has registered the sale of 849 thousand carbon credits. It has done so to a single buyer: the U.S. oil company Chevron.

Since that first transaction of 315,000 credits in October 2022, Chevron has redeemed credits from the project in the Cumbal paramos on five occasions, according to ColCX’s platform. That initial purchase was followed by one of 160,000 credits in December 2022, another of 194,000 in February of this year and one more of 180,000 last April. In all cases, its objective was — according to ColCX — to demonstrate carbon neutrality in order to be exempted from paying the carbon tax to the Colombian government.

When asked if it knew that the credits bought and redeemed came from a project that most inhabitants of the reservation that houses it are unaware of, Chevron told this journalistic alliance that "according to audit reports, it has the permits and approvals of the respective indigenous government authority and corresponding socialization processes were carried out." The oil company’s Colombia office added that it is in "continuous communication" with the developers, that they have not "reported or notified them about the existence of any conflict or eventualities" and that they even consulted them again as a result of this investigation.

Chevron also explained that its policy to support what it deems "an important market-based approach to achieving efficient carbon reductions" is to establish "strategic partnerships that enable us to achieve compliance standards." Its due diligence process for the credits it buys, the company said, consists of checking that the verification bodies that assess the projects are accredited in Colombia or by the International Accreditation Forum, and examining the projects' audit reports. Chevron declined to answer, due to "corporate confidentiality of information policies," which company it purchased these credits from and the amount paid for them. "Our offsets have a degree of compliance accepted by the governments in the regions where we operate," it added. (Chevron's full response can be read here).

This isn’t the first time Chevron’s environmental compensation scheme has been questioned. A week ago, a report by the non-governmental organization Corporate Accountability claimed that 93% of the carbon offsets Chevron bought and used globally between 2020 and 2022 are environmentally problematic. The oil company rejected the report’s findings, arguing that it is biased against the industry and paints an incomplete picture of its efforts to reduce its carbon footprint.

A sanctioned carbon advisor

The lack of transparency surrounding the Pachamama project isn’t the only thing that worries inhabitants of the Cumbal reservation. The name — and more specifically the background — of the person who appears in the letter of acceptance of the commercial offer to purchase the Redd+ project’s credits as a "witness" has also become a cause for alarm.

His name is Jorge Luis Tipas Colimba and he is an inhabitant of the reservation who was an alderman in the rural hamlet of Cuaspud, worked as a public official in the Cumbal mayor's office and was a departmental assemblymember. His political career was cut short when, in late 2015, the State Comptroller of Nariño found him responsible for administrative mismanagement in two different cases linked to contracts that he had supervised during his time as municipal planning secretary of Cumbal in 2012.

In a first case, in November 2015, the Comptroller's Office found Tipas responsible for the "unjustified loss of public resources" in a contract to supply gasoline for a dump truck destined for road maintenance in the Chiles reservation that was under repair in Pasto. According to the regional oversight body of public resources, Tipas did not supervise this contract and "untruthfully certified that the fuel and lubricants were used in a vehicle that was not being used in favor of the community." A month later, the same departmental Comptroller's Office declared him responsible for not having supervised ten contracts for repairs in Chiles’s cultural house, for not monitoring the use of construction materials and for not realizing that they were used in a different location than the one in the contract. In both cases, the Comptroller's Office determined that there was "damage to public assets" due to Tipas' "negligent actions," which it deemed "serious negligence of omissive character." The amount of these losses, according to the Comptroller's Office, was 102.3 million pesos (about 31 thousand dollars at the exchange rate on that date).

Those rulings brought him two of the harshest disciplinary sanctions in Colombia: In April 2016, the Inspector General's Office barred him from holding public office for ten years and an identical one to contract with the State. Both are in force until April 2026. (Several of the documents write Tipas with an 's' and others with a 'z', but refer to the same ID number).

Six years later, in March 2022, one month before the signing of the carbon project contract, the Comptroller of Nariño again ruled against Tipas in a third process also linked to his time at the Cumbal municipal government. According to the regional entity, it didn’t find "any trace (...) that allows to verify the execution" of an environmental restoration project in the Cumbal reservation or of 46,000 native tree seedlings that were paid for but never planted. Tipas argued that he was not appointed supervisor of these contracts, but the Comptroller's Office ruled against him on the grounds that "it cannot be minimized" that he didn’t verify the activities and still certified compliance. On that occasion, he was not held liable and clarified that "he did not participate in the deceit to obtain the resources intentionally."

Tipas did not respond to an interview request from this journalistic alliance about his role in the carbon project and his sanctions.

Problems for "mother earth”

For the inhabitants of the reservation on the slopes of the Cumbal volcano, the greatest irony is that the project promising to care for "the entire extension of the territory in the Gran Cumbal Reservation," as its contract says, has excluded them altogether.

"The authorities’ obligation is to make any project known: to use a loudspeaker to invite and gather the community, present the project to them and ask them how they feel about it. If the community agrees, it can be done. But you can't do it quietly," says 74-year-old Gilberto Valenzuela, who has been an alderman in Cuaical four times.

The sum of singularities — a project unknown to its beneficiaries, documents that aren’t public, undeclared links between developers and auditors, a certifier who refuses information to the community and a sanctioned project advisor — have sown doubts among them about its legitimacy. In addition, the project may not be complying with several of the social and environmental safeguards for this type of initiative, including transparency of information, consent and full participation of beneficiaries, and accountability of its results.

"Everything must be done with participation and dialogue. The accumulated knowledge of the community, its elders, women, young professionals and environmental organizations was not taken into account, but rather the negotiation was carried out in Bogota behind closed doors," says Omar Chiran, lawyer and member of the collective. In his opinion, the project has been "totally detrimental to the rights, processes and worldview of the indigenous peoples," leading them to consider filing a legal action, emulating that of the indigenous people of Pirá Paraná, which was selected for review by the country’s Constitutional Court.

This would allow them to correct, at the very least, that the project does benefit those who are protecting "mother earth" in Cumbal. "The communities that really care for the paramos and the forests have not benefited from it at all," says 50-year-old María Jael Cuaical, who leads a native plant nursery in the Guan area. In the seedbeds of her Sinchimaki association, where eleven families work, hundreds of trees from the high Andean forests — pumamaquis, caspimotes, capulies, chilcuaros and charmelanes — grow and are planted along the edges of the creeks that flow down from the paramo.

But, Cuaical says, "we are invisible."