Transporting undocumented migrants across America can seem like easy money – until everything goes wrong.

All James Matthew Bradley junior had to do was drive. He had been a trucker for 46 years and that was the only job he knew how to do anyway. On July 22nd 2017 he sat parked in a cul-de-sac in Laredo, a border city in Texas, and watched from his truck’s side mirrors as a series of vehicles pulled up to the back of his trailer, unloaded their contents and drove off. He wasn’t allowed to approach his cargo — there were strict rules around smuggling people, after all.

Bradley waited in the cab. Upholstered in white leather with black and red trim, it was luxurious, almost yacht-like. The temperature in Laredo had reached 106°F (41°C) that day, and although dusk was falling, it offered little relief. When enough light had drained from the sky and the last of the people had been loaded, it was time to leave. The trailer doors closed, and Bradley put the truck into gear.

The rig joined a stream of 18-wheelers bound for Interstate 35, which runs from the border, up through the heartland, to the shores of Lake Superior. From the onramp above the mesquite-covered plains, streetlights twinkled in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, on the other side of the Rio Grande. Bradley drove north for half an hour before it was time to stop: lights flashed in the distance, indicating a Border Patrol checkpoint ahead.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Bradley braked and rolled down his window for an agent in a green uniform, as a patrol dog circled the back of his 53-foot trailer. He shifted his weight from side to side, trying to calm his nerves. Seventy undocumented migrants, possibly many more, were inside.

The agent confirmed Bradley’s citizenship and waved him through. Just under two hours and 120 miles (193km) later, he pulled off at a Walmart near San Antonio city limits. He drove to the back of the parking lot and turned his rig around, obscuring the trailer doors. Bradley was followed by several SUVs and vans, which arrived to ferry the people in the trailer to stash houses across San Antonio, where payment for their journey was due. Someone from the smuggling network walked to the back of the trailer. He opened one of the doors and screamed.

After midnight, a Walmart employee called 911 to report a suspicious truck and people in distress, needing water. When officers arrived, one of them approached the back of the rig, a gallon of water in hand. He would later testify that he heard moaning and felt heat radiating from the trailer before climbing inside. When he did, he vomited twice. Many of the people inside were lying flat. Some were completely still. Others were having seizures and foaming at the mouth. The officer checked pulses. Some of the migrants had already died; those who were still breathing and conscious stared up at him blankly.

Someone from the smuggling network walked to the back of the trailer. He opened one of the doors and screamed

Bradley, who surrendered peacefully, had just presided over the deadliest smuggling attempt the nation had seen in 14 years. Ten people — migrants from Guatemala and Mexico, four of them teenagers — lost their lives. Or at least ten. Investigators never determined how many people had been packed into the trailer in Laredo — one survivor estimated 200 — or what happened to those who were driven off before the police arrived. Of the 29 survivors found at the scene, some would remain hospitalised for weeks.

One of the migrants, a man from Aguascalientes, Mexico, told investigators that the person who had closed the trailer door told him not to worry and said the refrigeration would be turned on. But the trailer was neither refrigerated nor ventilated, as Bradley was well aware. “It’s air-tight,” he told Homeland Security Investigations agents upon his arrest. “The refrigerator, it don’t even work on that thing, it wasn’t even running. You just gonna put people in there like that?” he asked. At first, he maintained that he had no idea how the people ended up in his trailer. But three months later, Bradley pleaded guilty to two counts: conspiracy to transport and transporting undocumented migrants resulting in death.

At sentencing, his lawyer, Alfredo Villarreal, argued that his client’s intellectual limitations made him an easy pawn for “professional smugglers” who had threatened him with violence if he failed to carry out the job. “James Bradley, regrettably and perhaps unwillingly, entered the dangerous world of moral complacency,” Villarreal told the court. The judge wasn’t sympathetic; he likened the conditions inside the trailer to torture. Bradley was given two concurrent life sentences without parole and sent to a federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana. Only one other person involved in the smuggling attempt was charged — Pedro Silva-Segura, a stash-house operator in Laredo who received a nine-year sentence.

I first heard about the tragedy days after visiting Laredo to report on an evangelical pastor who was rumoured to be collaborating with smugglers. I returned several times over the following months. Driving up I-35 from the border to my home in Austin, I frequently found myself stopping outside that San Antonio Walmart. Sitting in my car, I would look at the spot where Bradley had parked and wonder how a 60-year-old, one-legged truck driver with nearly half a century of experience on America’s interstates had found himself involved in something like this.

The toll of his particular case had been unusual, but I came to understand that the circumstances of the crime were not. By the time of Bradley’s smuggling attempt, the Border Patrol had apprehended some 225 migrants hidden inside commercial trucks in the Laredo area over the previous nine months, a rate that would soar in the years to come. In 2022, the most recent year for which statistics are available, as many migrants would be rescued from trucks around Laredo over a single summer. How, I wondered, does a commercial trucker start moonlighting in the multi-billion-dollar business of smuggling people through the borderlands, and why?

So I wrote to Bradley and asked him.

James Bradley has a peculiar voice: gravely, equal parts melodic and flat. It’s a voice of the American South, from which he hails, and the edge of the Great Plains, where he had maintained an address for three decades. But, more than anything, it is the voice of a man who has spent his life on the road, chain-smoking behind the wheel of a big rig – a person defined by transience. “The highway is my home, really,” he told me over the phone from Terre Haute.

Bradley was born in Florida in 1956. The name James came from his father, whom he did not know. The youngest of seven siblings, Bradley was mostly raised by his maternal grandmother in a tiny town near Gainesville. As a boy, he would sit on the front porch and wait for the logging truck to go by. “This was when I was a little bitty guy,” he said. “I could hear that truck coming around the curve and I would run out in the yard and want him to blow that horn.” In his decades on the road, he was always searching for a horn that sounded just like that truck’s, but he never found one. Whenever Bradley’s teachers asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, he’d say a truck driver. But he didn’t go to school much. He hid in the bushes when the school bus went by. He got Ds and Fs and dropped out by the time he was 13.

How had a 60-year-old, one-legged truck driver with nearly half a century of experience on America’s interstates found himself involved in something like this?

Bradley was 14 when his grandmother died. The way he remembers it, the hearse went in one direction and he walked away in the other. Bradley slept under bridges and inside drain pipes. It was dangerous to be a black kid alone on the road in the South. Once, in Alabama, a white man poked him in the chest and told him he’d better get out of town before the sun set. Bradley mentioned the incident a number of times to me; he believes that if the man hadn’t warned him, he’d be dead.

Hitchhiking across the country, he found a home among truckers. They gave him food and let him sleep in their cabs. Some taught him how to drive and fix trucks; when Bradley was experienced enough, one took him to a small town in Mississippi to get his chauffeur’s licence — all a person needed to drive commercial trucks at the time. He paid $54 and stood in front of a blue curtain. The camera flashed, and he became a truck driver. He was only 14 years old, but he looked 17, the legal age for obtaining a licence. He adopted his CB radio handle, “Bear”, both on and off the road. “That’s all I know, trucks,” he told me. “I don’t know nothing else.”

Bradley came of age on the road when the figure of the American truck driver was steeped in the myth of the frontier. It is a rugged identity to which he still clings tightly. He refers to himself as a “black cowboy” and an “outlaw” and describes bar fights and other tales from his decades in trucking as “like old Western stuff”. I often felt as if I was speaking with an actor playing a 1970s Hollywood version of a trucker.

Trucking for Bradley was more than a job; it was a matter of soul. “It’s not sitting behind a wheel saying I’m a truck driver,” he said. “No, it’s more than that.” The only narrative that seemed to make sense for him was that of the open road. But in the decades since he became a truck driver, that road had changed entirely.

In the early 1970s, when Bradley began his career, driving a truck was one of the best blue-collar jobs in America. More than 80% of the trucking workforce was unionised, nearly all with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, then the country’s largest industrial union, and freight routes and rates were tightly regulated by the federal government. But as the decade wore on, fuel prices soared, inflation reached crisis levels, independent drivers staged nationwide strikes and calls for more competition gained traction in Washington. In 1980 President Jimmy Carter signed the Motor Carrier Act, a broad set of measures aimed at deregulating interstate trucking.

Trucking companies, for the most part, could now haul what they wanted, where they wanted, at whatever price the market would accept. New carriers hit the road by the thousands as older carriers shut down, gutting the Teamsters. Shipping rates and wages plummeted. Consumers benefited — low prices at big-box retailers depended on access to cheap, fast freight — at the cost of the drivers who delivered their goods. As of 2022, the most recent year for which Bureau of Labour Statistics data is available, the median annual pay for a truck driver was about $50,000. While there has been an upward pressure on wages in recent years due to low driver retention and rising freight rates, adjusting for inflation, long-haul truckers today are still earning roughly half of what they were in 1980.

Bradley spent the majority of his career hauling meat and produce for small freight companies. In the years after deregulation, he remembers having to run harder and drive farther to make a living, sometimes more than 5,000 miles a week, requiring him to doctor his own logbooks. (Long-haul truckers are not supposed to drive more than 11 hours in a single day, but Bradley found himself on the road for 15, 18, even 20 hours, popping amphetamines to stay awake.) He would be out for as long as six weeks at a time with only one- or two-day breaks between runs, which he told me was his preference. He had been married four times and had three kids, but didn’t consider himself a family man. “I’m basically on the road all the time,” he said, still using the present tense from behind bars.

The itinerant life turned Bradley into a loner, but he had friends from the road. One of them was Paul Terry. They were both black men who had started trucking in the early 1970s, when only 3% of long-haul truckers were black, and lived in Colorado, where they would meet for barbecues on breaks from driving. Terry, who is 75 years old and still works as a long-haul trucker, described Bradley as a loyal friend. But he was “not on top of the programme,” as he put it. “You could tell him it’s snowing outside and the sun is shining, and he’d believe it.” (A neuropsychological evaluation presented at Bradley’s sentencing determined that he has an IQ of 69.)

Terry also remembered that Bradley shared the dream of most truckers: buying his own truck. This would make him an “owner-operator,” meaning he could work as an independent contractor. Around 10% of America’s 3.6m truckers are owner-operators. For Bradley, this seemed like a distant possibility.

Laredo’s truck stops, strip clubs, motels and parking lots are known as places where you can find work in the shadows — or where the work will find you

Yet, in 2017, Bradley bought a custom 1999 Peterbilt, in his own name, from Outlaw Iron, a truck shop in Wisconsin. “Peterbilt is the Cadillac of all trucks,” Bradley explained. “If you drivin’ a Pete, you somebody.” Justin McDaniel, the owner of Outlaw Iron, told me about the moment Bradley saw his truck in the shop for the first time. Gazing up at the Peterbilt, painted black and white with a red stripe beneath the windows, Bradley was speechless. Eventually, he started to cry.

The truck cost $95,000 — Bradley got a loan for $20,000 and paid the rest in cash, in, McDaniel recalled, $20 bills. (Bradley claimed to me that “another fellow” lent him this large sum of cash. Whenever I pressed him for more details, he got cagey.) Terry was mystified — Bradley had occasionally relied on him to buy cigarettes and clothes. How could he suddenly afford such an enviable truck? “It just does not make any sense whatsoever,” Terry remembered thinking.

Only a few months after buying the truck of his dreams, Bradley was forced to take a break from the road. In May 2017, his right leg was amputated below the knee, a complication of a long struggle with diabetes. He got a prosthetic in July, but driving with it was extremely painful. Legally, Bradley’s loss of limb required him to obtain special clearance from the Department of Transportation to drive a commercial truck. He failed to do so, which meant he was officially barred from the road. But neither that nor the pain stopped him. When Pyle Transportation, the Iowa-based carrier he had been driving for, offered him a job, he said yes, agreeing to deliver a 53-foot trailer to Brownsville, a border city in far east Texas. On July 20th, seven days after getting the prosthetic, he set out for Texas from Iowa. But he didn’t cut south-east to Brownsville upon reaching San Antonio. He kept going due south, to Laredo.

Laredo is the busiest inland trade port in the entire country. “Heaven for freight,” as one trucker there put it to me, “the freight capital of America, the heart and soul of the logistics industry.” The city sits on the border with Nuevo Laredo, where Carretera Federal 57, the highway that runs from Mexico City through Monterrey, meets I-35. Laredo’s streets are clogged with so many big rigs that driving through the city in a car can feel like trying to converse in a foreign language you only half understand. Signs in parking lots across the city centre warn NO TRACTOR TRAILER PARKING, so truckers, if they can secure a spot, park in giant lots on the outskirts of town. Inside truck stops, they watch television while waiting their turn for a shower — on a hot summer day, they might wait a few hours. They buy pallets of water bottles and 12-packs of beer, which they take back to their cab or maybe across the street — the strip club across from Laredo’s biggest truck stop is BYOB.

Before 1987, Laredo was a quiet city of about 110,000 with a quaint downtown and high unemployment. Many of its roads were still unpaved. Then, Mexico slashed tariffs on American imports and everything changed. Exports to Mexico tripled over the next five years, along with the number of trucks passing through town. Suddenly, Laredo was a boomtown.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was enacted in 1994, eliminating tariffs on most goods and accelerating the local pace of growth. Laredo’s population surpassed 180,000 by the end of the decade, exports moving south through the city nearly doubled, and imports moving north rose by about 140%. I-35 earned a new nickname: “The NAFTA Highway.”

At the same time as the border was opening to car parts and produce and textiles, it was closing to migrants. The Border Patrol more than doubled its ranks along the south-west border in the first five years of NAFTA's implementation. It concentrated its agents at popular crossing points in urban areas, forcing migrants to cross through desolate stretches of deserts and thorny plains — landscapes that the Border Patrol termed “hostile terrain” in a 1994 plan. Video-surveillance towers were installed in Laredo, along with helicopter pads and floodlights. At night, the Rio Grande glowed.

As the aftershocks of trade liberalisation rippled through the Mexican countryside, displacing millions of farmers, rates of emigration soared. A robust smuggling industry emerged, providing professional help to those looking to make it across the newly militarised borderlands. Crossing the checkpoints, which extend as far as 100 miles into the interior, was sometimes more of a challenge than crossing the border itself. The stretch of country between border and checkpoint is known as la jaula de oro, the golden cage. Escaping the cage required circumventing the checkpoint by walking for days across the hostile terrain. Or making oneself invisible and moving through the checkpoint itself, like freight. This is where truck drivers come in.

In Laredo, truckers have to wait a long time to pick up freight — often hours, occasionally days. Long-haul drivers get paid per mile or per load, so downtime generally goes uncompensated. This means that the city is home to a large transient population of idle and cash-strapped workers. Organised crime takes advantage of them. Laredo’s truck stops, strip clubs, motels and parking lots are known as places where you can find work in the shadows — or where the work will find you.

“I didn’t know if they was gonna put a bullet in my head at one of the drops. It was very scary”

Jess Graham, a trucker from Georgia, recalled being stuck overnight in Laredo a few years ago with a trailer full of ham and a broken refrigeration system. While she was waiting outside a warehouse for after-hours repairs, a white sedan drove past her rig and circled back. It struck Graham as the sort of vehicle you’d take your kids to school in. She rolled down her window, thinking the driver was lost and going to ask her for directions. Instead, he asked if she would like to make some extra money. “Yeah, no, I’m good,” she told him.

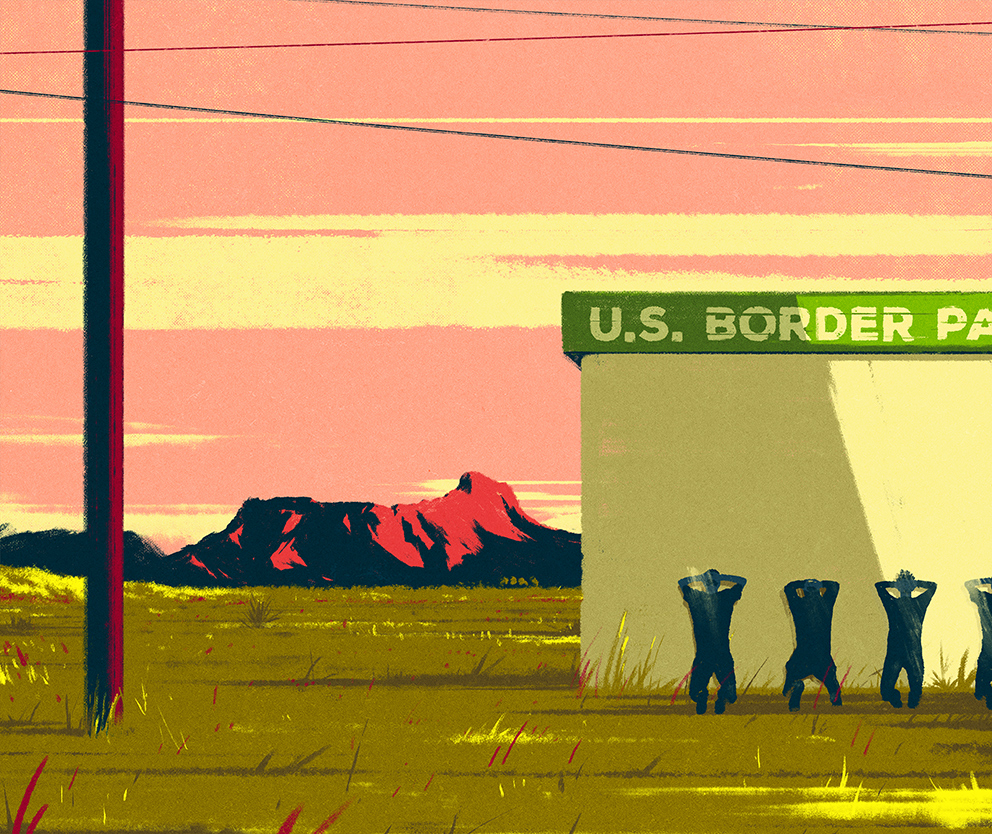

A few months later, Graham was going through the checkpoint north of Laredo on I-35 when she saw a trailer pulled off to the side. About 15 men were on their knees on the pavement. Another 15 were lined up against the wall of the Border Patrol station — including the driver of the truck, on his knees, his hands behind his head.

Graham understood why he might have done it. She recalled starting out as a trucker over a decade ago, working for a big carrier and homeschooling her daughter on the road. Like a lot of long-haul drivers, she was barely getting by. “I don’t know if I would’ve turned it down at that point in my life,” she told me. “Once you get sucked into that world, you’re in it.”

In February 2017, Bradley says, he was unloading meat at a warehouse on the outskirts of Laredo when a man approached him. Bradley assumed he was a lumper — trucker-speak for someone who helps load and unload freight. “Would you like to make some money, quick?” the man asked. “You going up to San Antone?” He said he had two or three people that Bradley could take for $2,000. They exchanged numbers.

After contemplating the offer for a few hours, Bradley got in touch: he was in. “That kind of money, you know, it just come up to me out of nowhere like that,” he recalled. The plan was for him to park by a fire hydrant on a quiet cul-de-sac. Loading would start around 5pm. Bradley would remain in the truck so that he would be unidentifiable to the passengers. Once the sun set — a time Bradley calls “dusk dark” — it would be time to leave.

He told himself to remain calm as he drove. About 20,000 trucks pass through the I-35 Border Patrol checkpoint every day, only a fraction of which are flagged for further inspection. One of the things agents look for is what they call “nervous behaviour.” And Bradley was extremely nervous the first trip. “I had butterflies in my face,” he told me. But he made it through to the destination — a motel parking lot in San Antonio — without incident. The people in his trailer were unloaded, and the man who had recruited Bradley came to the window and paid him. He was in the game now.

Over the next three months, Bradley made another four or five trips on behalf of the same man, making drops all across San Antonio. “They wind you into it, 1,000, 2,000 [dollars], and then they bring you on up to where they just want to use you,” he reflected. “They didn’t care for people’s lives or nobody.” Bradley had as little to do with unloading as he did with loading. He sat in the cab as migrants were led away from the trailer according to the colour they were wearing, each indicating a different smuggling network. Drivers aren’t typically hired to work for particular networks, but for a middleman who co-ordinates checkpoint logistics among them. A retired Homeland Security Investigations agent who worked on Bradley’s case told me that these middlemen can be extremely territorial over their drivers, and generally regard them as disposable. During the drops, Bradley felt as nervous as he had at the checkpoint, possibly more. “I didn’t know if they was gonna put a bullet in my head at one of the drops. It was very scary.”

Oscar O. Peña, a criminal-defence lawyer in Laredo who has represented truckers in smuggling cases since 1997, told me that his clients typically make five to seven drops before they’re caught. The same logic applies to smuggling people as it does to smuggling drugs: if you get 90% of your product through the checkpoint, you can afford to surrender 10%. “It’s a numbers game, like the Las Vegas casinos,” Peña said, “and the drivers, they really get sacrificed.”

In recent years, Peña has seen more trucker clients rationalise smuggling as a pseudo-humanitarian endeavour. They would never smuggle marijuana or cocaine, they say, and convince themselves they’re helping migrants — who are fleeing poverty, violence, or both — “live the American dream, or whatever.” But drivers have no control over what is happening inside the trailer — the temperature, the number of people onboard, the availability of water. “The essence of the crime is treating people like freight, the commoditisation of human beings,” said Peña. “These people don’t care about the American dream, they just care about money.”

In 2020, Bradley was transferred from Terre Haute to a medical prison in Missouri, where his other leg was amputated. We continued to talk over the phone for 15 minutes at a time, a Bureau of Prisons rule. Bradley’s voice would brighten whenever he spoke about the road, but as soon as the subject turned to that July night, his tone grew pained.

It wasn’t just the boots that Bradley wanted too badly, or the Peterbilt. It was the story they allowed him to tell about himself

“The families of the people that went in my truck when it happened, it still hurts,” he said. I asked what he would tell other truckers. “Please don’t do it,” he said. “It looks like good money, it’s not good money. That’s what they do. All about the almighty dollar, all they doing is they gonna give you so much money. They give you money just to get you sucked in.”

But every time I pressed Bradley on how he spent his smuggling profits, he got evasive, suggesting that they went towards “cowboy boots” (he spoke of a fondness for alligator and snakeskin) or “chrome on my truck, big pipes.” Once, when I asked him bluntly how he came to buy his truck, he got so upset that he hung up the phone.

At that moment, I thought back to what he’d told me about his first amputation. “I always wore cowboy boots and I wear a j-toe” — a boot with a very pointy, narrow toe box. “My toes be stacked up there in my boots, and with me being a diabetic and all that, it was bad on my toes, that’s what caused the amputation.” He had lost a leg over his insistence on wearing a particular style of cowboy boots. But it wasn’t just the boots that Bradley wanted too badly, or the Peterbilt. It was the story they allowed him to tell about himself.

In June 2022, 48 migrants from Mexico and Central America were found dead in and around a trailer three miles from the Walmart where Bradley had parked. Five more people died in the hospital. It was the deadliest known smuggling attempt in American history. The truck had departed from Laredo without a functioning refrigeration system. The driver, Homero Zamorano junior, a 45-year-old from east Texas, was high on meth.

Bradley called me the next day, after his sister had told him what had happened. He wanted to talk a lot that week. I asked how the news was making him feel. “It tears me up, it bothers me real bad,” he said. “It’s just not me, I never — all I ever did was trucking, to do that and harm somebody, it wasn’t …” He switched to the present tense. “It ain’t me.”

Over the following months, Bradley continued to call me. His diabetes deteriorated, keeping him in and out of the prison’s medical ward. He told me he didn’t watch television with the other inmates, preferring to sit quietly in his wheelchair and think. “I got so much stuff out there on the road to remember,” he said. We discussed a new federal rule requiring long-haulers to connect their truck to an electronic-logging device, which monitors their driving hours for them. He laughed out loud at the thought of being subject to such surveillance. “I’m an outlaw,” Bradley said, “no way in the world I could be a trucker no more, no kind of way.”