Months of reporting into Xcel Energy’s Valmont coal ash site reveals groundwater contamination with scant oversight from Boulder area officials.

When professional beekeeper Christopher Borke and his wife, Meghan, purchased their house in 2021 across the street from Boulder’s Valmont Power Station, they did so planning to live there for the rest of their lives.

“Married and buried,” Borke said.

From where their house sits on a rise, the Borkes can see smokestacks loom as a reminder of almost a century of burning coal at Boulder’s edge. Smoke hasn’t risen from the stacks since 2017, when Xcel Energy, the plant’s owner, retired the facility’s last coal unit and converted it to burn natural gas.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

But the end of one pollution problem at the Valmont Power Station — dirty air from coal — has given way to evidence of another: contaminated groundwater.

“We are critically beholden to groundwater in the area,” said Borke. “In my mind, it is a matter of when, not if, the wells get contaminated.”

Borke has reason to be concerned. More than 90 years of burning coal for electricity at Valmont left a little-known legacy of chemical waste. The powdery residue of burned coal – known as coal ash – was removed over decades from inside smokestacks and boilers and transferred into several nearby landfills and storage ponds on site.

Today, most of the dry ash lies underground in an unlined landfill owned by Xcel just east of Boulder city limits. The dump sprawls nearly 15 acres between Valmont Butte and Leggett Reservoir, largely out of public sight and mind. Yet hidden behind a grassy hill is 1.6 million tons of coal ash waste that could fill almost 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools or pave more than 2,000 miles of road. Xcel has admitted in public documents that the ash — which contains a blend of minerals such as quartz and clay, as well as toxic heavy metals — is in direct contact with groundwater, but the company has yet to implement a cleanup plan. Xcel’s own public models raise concern that the contamination is spreading toward residential areas.

“We are still investigating potential violations. But based on results from the assessment monitoring performed in accordance with the Solid Waste Regulations, Xcel Energy appears to be out of compliance” with two sections of state rules, said Venissa Ledesma, a spokesperson at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE).

Coal ash was thrust into the national conversation in 2008, after a disastrous spill in Kingston, Tennessee, released one billion gallons of ash into the Emory River, causing hundreds of cleanup workers to be exposed to hazardous heavy metals and radioactive particles they say resulted in illnesses, some fatal. Seven years later, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved the first regulation governing storage and monitoring of waste at more than a thousand coal ash dumps nationwide. Under the rule, Xcel is required to test groundwater for dangerous contaminants at Valmont and make its data public. It has done this since 2017.

For six consecutive years Xcel has reported groundwater contaminants at unsafe levels. These results have barely registered in Boulder.

In interviews, Boulder County and City of Boulder officials seemed unaware of pollution issues at the site, raising questions about who is responsible for protecting the health of nearby residents.

“We don’t have any role to play here,” Boulder County Commissioner Claire Levy said in an interview. “My general approach is to assume the best, assume everybody’s doing their job and doing it faithfully.”

In fact, the EPA’s rules lack urgency. While the agency requires action to fix contaminated groundwater, there isn’t a specific deadline to do so.

For months, graduate students at the University of Colorado Boulder, along with Boulder Reporting Lab and the Center for Environmental Journalism, examined the extent of contamination from the coal ash site to understand potential impacts to human health and Xcel’s plans for cleanup. What’s happening at the Valmont Power Station is important not only for Boulder residents, but also for the six other communities in Colorado where Xcel has coal ash stored, and for the 42 other states where landfills exist — landfills that are often loosely regulated with little local oversight.

Our investigation reveals that the federal EPA regulation — known as the Coal Combustion Residuals rule, or CCR — grants utilities considerable leeway in determining how and when to comply, according to lawyers specializing in coal ash issues. In the meantime at Valmont, our investigation found:

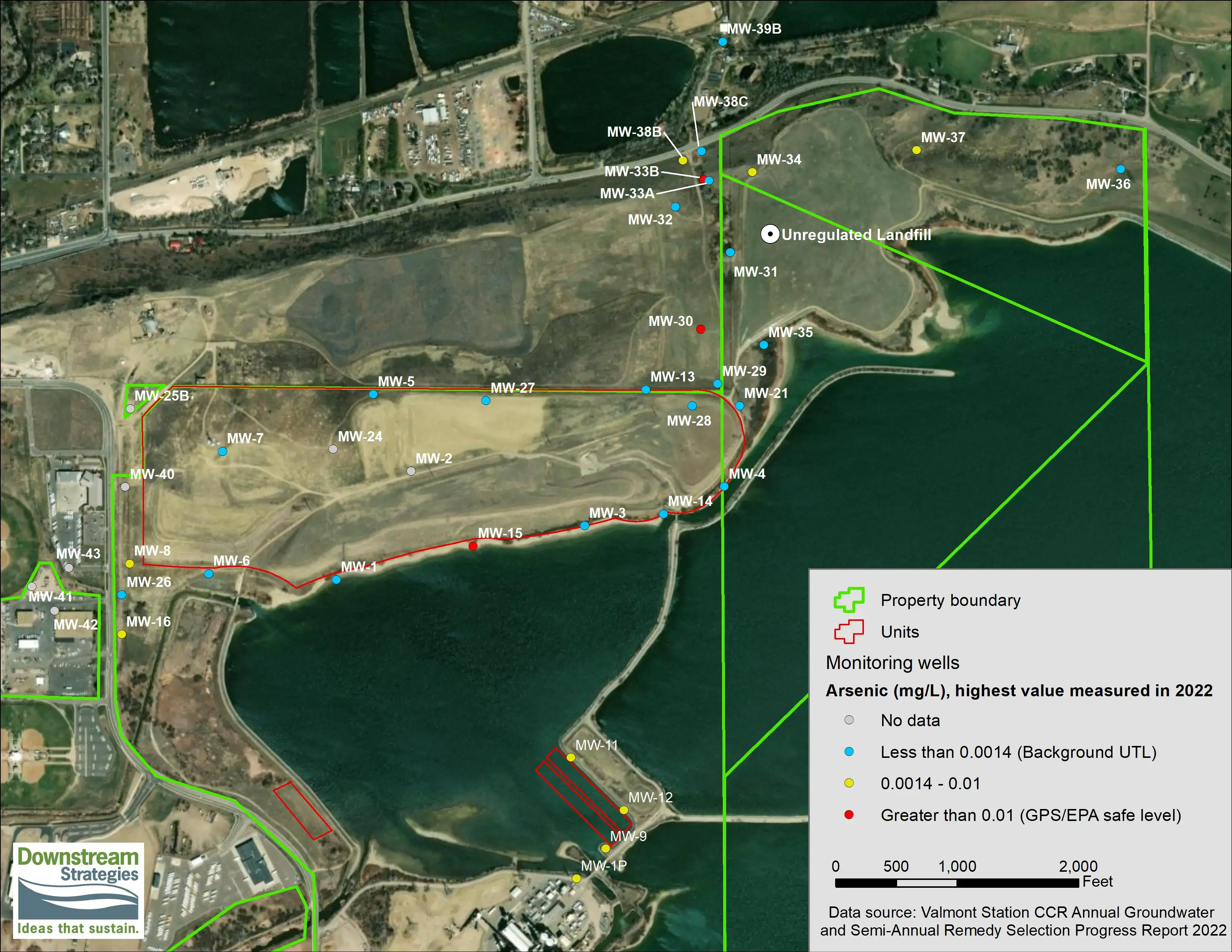

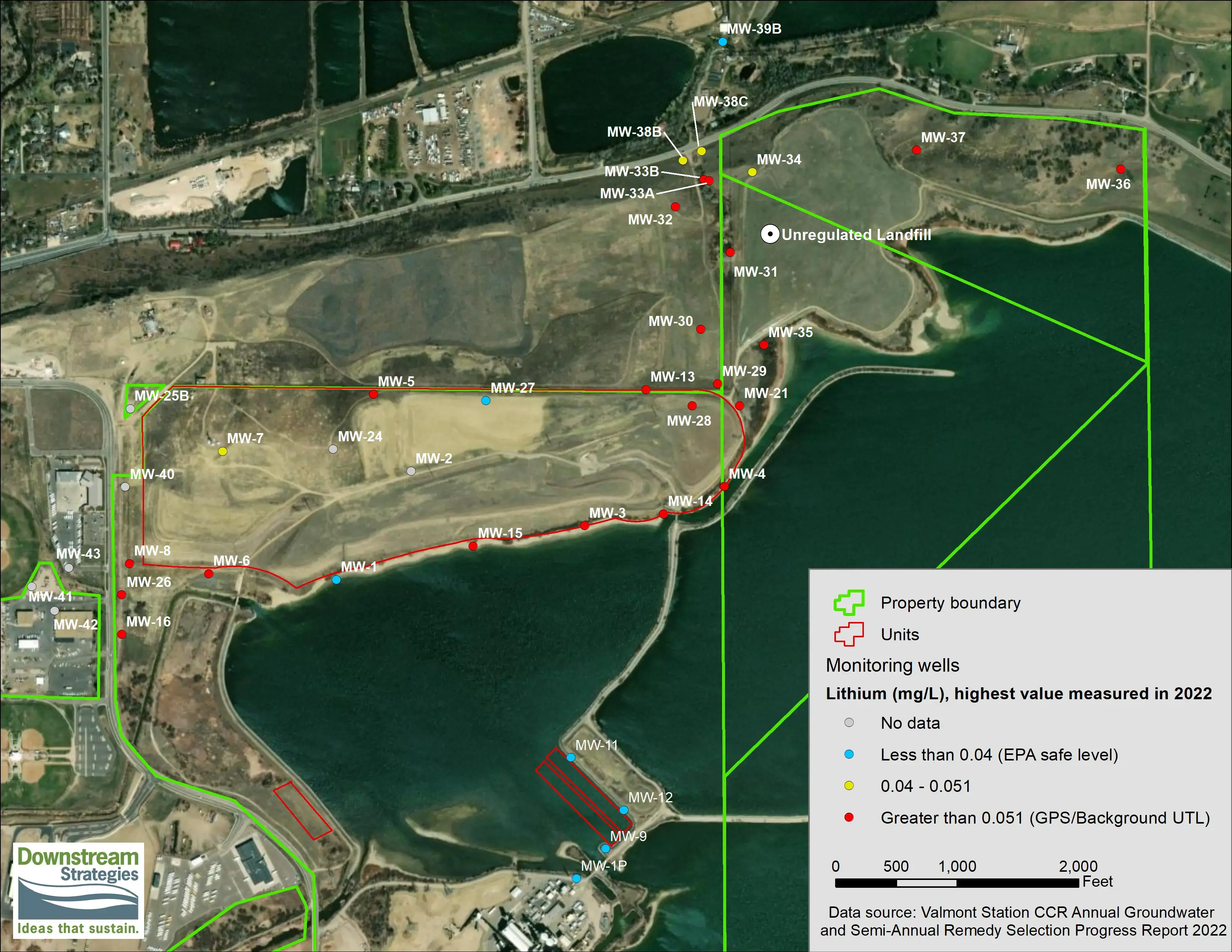

- Groundwater is contaminated. The Valmont site has been leaking contaminants into groundwater at levels the EPA considers unsafe for human health since at least 2017. In 2018, as part of its required reporting under the EPA rule, Xcel detected “statistically significant levels” of cobalt, molybdenum, arsenic, lithium and selenium in the groundwater at the site. Prolonged exposure to high levels of these heavy metal contaminants can lead to liver and kidney damage, intestinal problems, anemia and skin disorders.

- Deadlines for action are vague. Because Xcel found concerning levels of contamination year after year, the company was required under the EPA rule to address contamination “as soon as feasible.” Xcel has yet to implement its plan to do so.

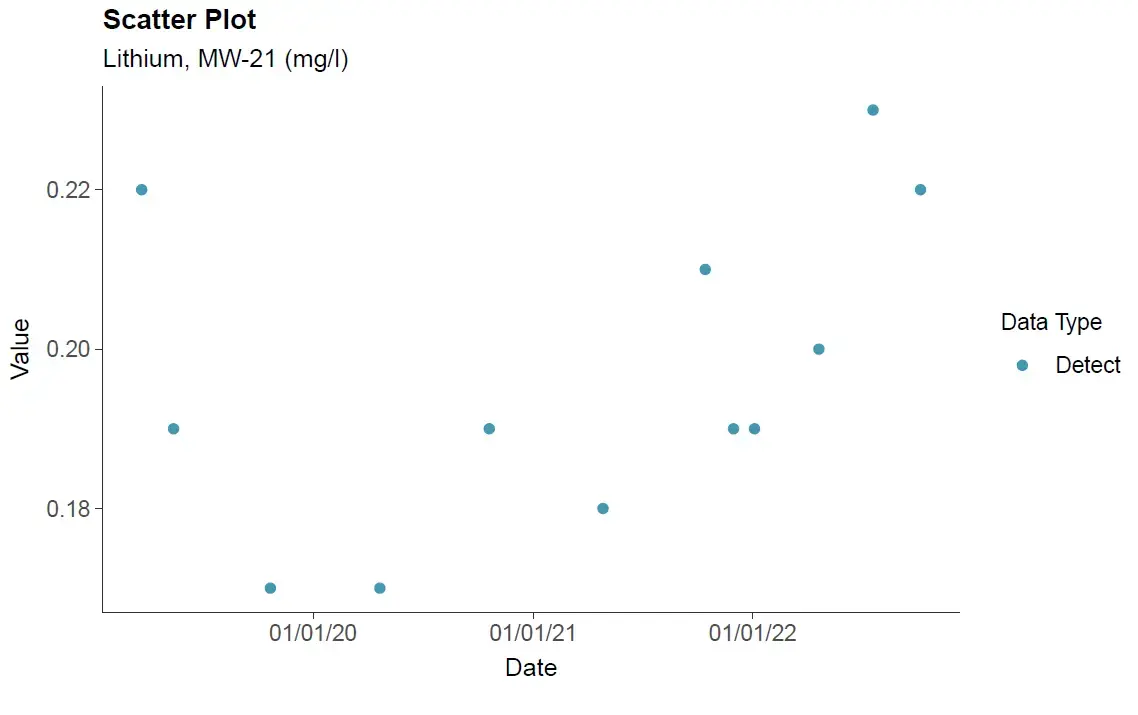

- Contamination is moving offsite. Contamination appears to have traveled toward a residential area that sits to the north and east of the plant, according to Xcel’s public reports. It remains unclear how far some of these contaminants have traveled because monitoring wells currently stop just beyond Xcel’s property boundary. Xcel tested 10 nearby residential wells in 2022 and found that lithium, a heavy metal, exceeded safe levels in at least one. Xcel has not made public the precise locations of these wells, and the company denied our requests for this information.

- An unregulated landfill may be leaking. Another landfill at Valmont might be leaking too, according to Xcel’s maps modeling groundwater contamination. But because this unregulated, and inactive, landfill was closed before the EPA passed regulations in 2015, it is not subject to EPA regulations, and is thus not being monitored for contamination. Under a new rule proposed in May 2023 this will change, however.

- Some data required to be public is not accessible. Though Xcel has links to regulatory documents posted on its website, we found that many of the links to reports on the Valmont Plant were chronically broken during the course of our investigation. At another Xcel site, the Comanche Power Plant in Pueblo, the EPA in 2022 imposed a $925,000 civil penalty on the company, which operates in the state through its subsidiary Public Service Company of Colorado, for violating the coal ash rule. Infractions included failing to post reports on a publicly available website.

Xcel acknowledged there is coal ash in the groundwater at Valmont and emphasized the need for “further evaluation.”

“We’ve expanded our monitoring network to include additional wells on the property and on nearby adjacent properties to the North and West of Valmont Station so we can better understand the situation,” Xcel spokesperson Michelle Aguayo wrote in an email. The company is planning to eventually remove the ash, and in the meantime, it is working on the specifics for removing and treating the contaminated water, she added.

In response to a question about being out of compliance with state solid waste regulations, Aguayo said, “We are working with the EPA, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment and Boulder County as we implement these steps in compliance with the Colorado Solid Waste Regulations and federal Coal Combustion Residuals Rule, including selection and implementation of a remedy to address groundwater conditions.”

Despite the confirmed presence of coal ash in groundwater and related concerns, environmental advocates consider the Valmont site relatively well managed, at least when compared to other coal ash sites. In 2018, Xcel removed all coal ash from its ash storage ponds, relocating it to the dry landfill before following federal rules for closing ponds. Xcel also self-reported some of its non-compliance with EPA’s regulation and proactively tested some nearby private wells.

Several people interviewed, however, suggested this is a sign of how low the bar is for utilities.

“Valmont is one of the only places I’m aware of where the owner has noticed that there’s landfill ash in contact with groundwater, and taken notice of it, and plans to do something about it,” said Abel Russ, a senior attorney at the Environmental Integrity Project and lead author of a 2022 report assessing the hidden risks of coal ash sites nationwide.

Russ also said Xcel is monitoring groundwater in a way that is “more thorough than the norm.”

But understanding what the data means to public health is beyond the ability of most people.

For our team to report this story, we had to hire independent consultants with expertise in hydrology, water quality and environmental safety to assess the publicly available groundwater data and compliance documents. A grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting funded this analysis.

“You really have to have an expert in order to figure it out,” said Frank Holleman, an attorney with Southern Environmental Law Center, which has been involved in coal ash lawsuits against utilities.

According to some experts who work on coal ash issues, this is in part by design.

“These results could have been clearly presented in a single table,” said Lisa Evans, senior counsel for EarthJustice, which has sued the EPA over lax coal ash regulations. “Most residents near waste sites are unaware that these reports even exist. It’s crazy to put the burden on the public to enforce a toxic waste rule. This is the responsibility of state and federal regulators.”

Leslie Glustrom, a Boulder climate activist and a trained biochemist who has been pushing county officials to intervene in this issue for years, said because “coal ash is largely an invisible problem, the community has been unaware” of it.

Groundwater contamination expected to ‘persist for many years’

U.S. utilities spawned roughly five billion tons of toxic coal ash over the last century of coal burning. The ash was mostly dumped into impoundment ponds or surface landfills near coal plants — often next to lakes, rivers or reservoirs — and mixed with water. Many sites lacked liners to protect nearby groundwater.

“There was a very simple answer to how this industrial waste should have been handled,” Holleman said, stating that to protect human health, “it should have been moved to a dry landfill, lined and separated from water.”

“Utilities did exactly the opposite of that,” he continued. “They mixed this coal ash with water, creating water pollution that did not have to exist.”

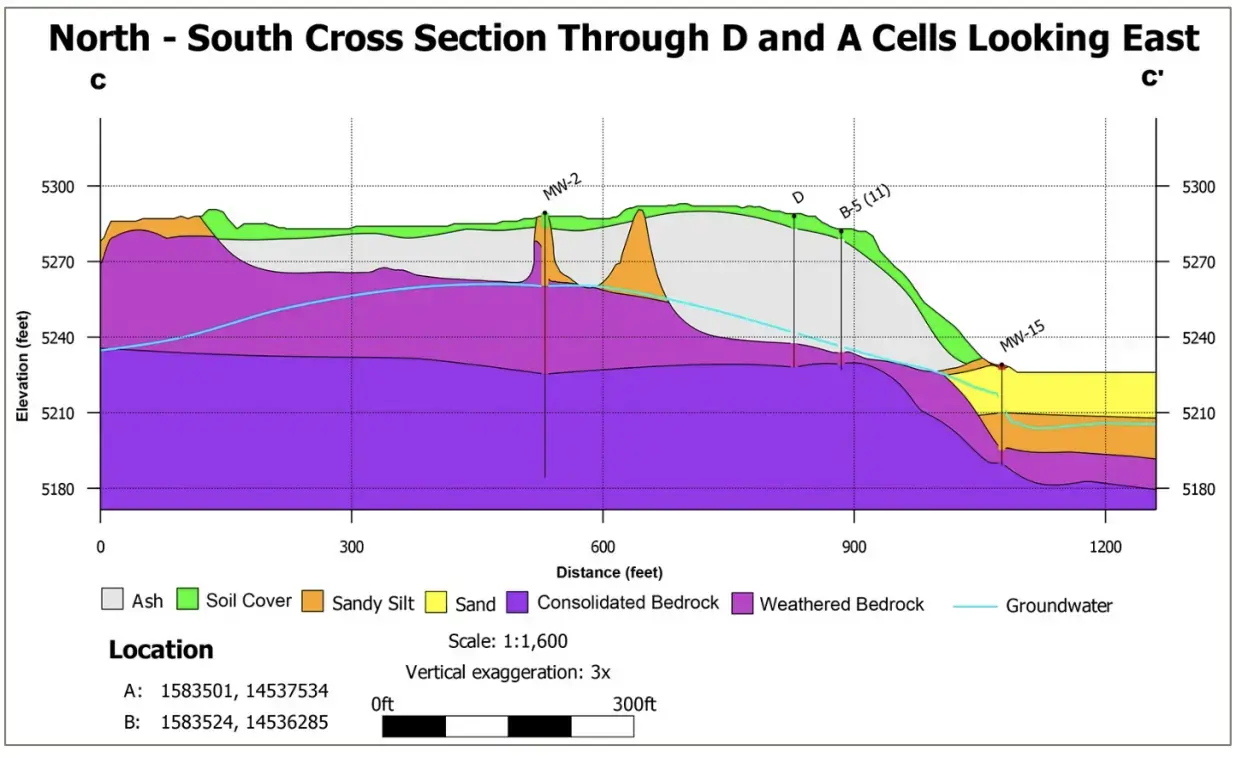

At Valmont, the coal ash was moved to a dry landfill that sits adjacent to three reservoirs. In the landfill’s deepest section, ash touches groundwater. That tainted water is migrating underground, away from the site, according to Xcel’s reports.

According to Xcel, groundwater beneath the Valmont plant is flowing at about an inch a year, at its fastest. Because the contaminated water is moving so slowly underground, Xcel’s models suggest the extent of the pollution hasn’t come close to reaching its peak.

“The longer we wait, the worse it’s going to get,” said Lauren Magliozzi, a University of Colorado hydrology Ph.D. candidate who studies geochemistry and water quality. “If I were them, I’d want to get this fixed sooner rather than later.”

But the EPA’s 2015 rule only stopped utilities from adding waste to most unlined landfills — which Xcel has done — and required them to monitor for contaminated groundwater. Xcel released its first groundwater report for the Valmont plant in 2017, the year coal burning stopped. The report revealed sulfate, boron, chloride and calcium above naturally occurring levels, according to Downstream Strategies, the consulting firm we contracted to analyze Xcel’s water quality data and groundwater reports.

And since 2017, Xcel has added cobalt, molybdenum, arsenic, lithium and selenium to the list of toxins found at unsafe levels. According to an EPA health risk assessment, arsenic in coal ash poses the greatest health risk among these chemicals, including an elevated risk of various cancers, as well as nausea, vomiting, abnormal heart rhythms and vascular damage.

In 2022, contaminants exceeded their health-based thresholds in 27 of 45 monitoring wells, according to Downstream’s analysis. In response, Xcel’s Aguayo said, “there are no offsite [water] wells that are used by the public for drinking water with any GPS [groundwater protection standard] exceedances.”

At least one monitoring well northeast of the landfill shows a clear trend of increasing lithium, a contaminant that has been associated in worst cases with kidney, nervous system and thyroid dysfunction. Levels there have been above the safe level since 2019.

Downstream Strategies also identified in Xcel’s public data that radium, a radioactive gas linked to cancer, exists at the landfill and beyond the Valmont property boundary “at levels greater than background concentrations on at least one sampling date since 2020” at multiple wells.

“We continue to monitor for radium in all wells and compare to background values and have not had any exceedances of groundwater protection standards at statistically significant levels to trigger corrective action,” Aguayo wrote in an email.

Methodology for determining safe levels

Downstream Strategies analyzed Xcel’s most recent groundwater monitoring data from 2022, comparing it to health-based thresholds set by the EPA. For arsenic, selenium and cobalt, Downstream used the same standards Xcel applied in 2022 (referred to as groundwater protection standards or GPSs). However, for lithium, Downstream adopted the stricter EPA standards, as Xcel’s limits were less stringent. Since Xcel didn’t establish specific GPSs for boron and sulfate in 2022, Downstream also relied on the EPA’s health standards to assess if these contaminants exceeded safe levels a Valmont.

The good news is that the removal of ash from its storage ponds in 2018 seems to have lowered pollution levels in that area.

But the landfill — where all that ash was later deposited — is continuing to cause groundwater contamination.

Xcel is using a groundwater computer model to figure out the extent of the spread. But the utility has said in its public documents it didn’t have enough data for its initial model to accurately pinpoint how far the plume of contamination has traveled.

“The plume likely extends beyond the Valmont property boundary to the north and east of the landfill, but how far is yet to be determined,” Downstream Strategies noted.

To address this issue, Xcel has been installing additional monitoring wells farther from the landfill, according to its spokesperson and public documents.

Meanwhile, ash removal is years away, the company has said.

“Groundwater contamination will likely persist for many years without implementation of a proper remedy,” according to Downstream.

Xcel suggested it doesn’t see the contamination as a threat.

“From our current testing there is no evidence that anyone is drinking water in the area with lithium or selenium levels above the groundwater protection standards,” Aguyo, the Xcel spokesperson, said in an emailed response. She added, “Lithium and selenium are naturally occurring elements found in rocks, soil, and groundwater. Lithium is also a substance found in certain medicines. Selenium is an essential nutrient often added to vitamins. Like most substances, both can be potentially harmful if very large amounts are ingested.”

But lack of evidence that anyone is drinking lithium-contaminated water does not necessarily mean the contamination isn’t present.

“There is one private well where we found lithium at levels above groundwater protection standards,” Aguayo wrote. “Even though water from that well is treated before consumption, we plan to provide an alternative water source at the property owner’s request while we continue to gather more information.”

In interviews, some nearby residents said they were aware that the groundwater contamination might be spreading toward their properties or farms. Most would not speak on the record due to privacy concerns.

“There are lots of farms in this area,” said one resident who asked to remain anonymous. “This is people’s food, and people’s businesses. If there is something wrong with the water in this area then that is their livelihood too.”

These residents are outside the city’s boundaries and do not have access to the City of Boulder’s water services. Several said they either pay to have water shipped in or have heavy-duty filtration systems.

Some, including Borke, want to be connected to the City of Boulder’s water system but feel powerless to affect policy decisions.

“We are on the demarcation of the city lines,” Borke said. But “even though the plume is expanding into this area, we don’t have any chance to put our vote towards these issues.”

The City of Boulder deferred all questions to Boulder County. “The city has no authority nor decision making over the facility nor the issues related to ash disposal,” said Emily Sandoval, senior communications program manager for the city’s sustainability office.

Who’s in charge of watchdogging the watchdog?

Under state regulations, the site falls under solid waste management rules. But neither the state nor the county is required to ensure Xcel is in compliance with the EPA’s rule.

In 2020, Boulder County contracted with two consulting firms, Pinyon Environmental and Integral Consulting, to provide an assessment of Xcel’s clean-up progress at the Valmont station. The goal was to make sure Xcel was on the right track with monitoring the spread of the contamination and finding a solution, Joe Malinowski, Boulder County’s environmental health division manager, said.

Pinyon’s report raised concern about the landfill’s contact with groundwater. In terms of contamination levels, the concerns “are real and need to be considered, but they really don’t rise to any kind of a threat level,” said Bill Cutler, principal scientist for Integral Consulting, during a 2020 Board of County Commissioners meeting. He added, “We need to watch it.”

The report also raised questions about potential contamination above ground in Leggett Reservoir. It cited the proximity of the landfill to the Leggett Reservoir and the decades of wind erosion that could have blown dry ash into the reservoir.

"We have tested the surface water in Leggett and there [is] no exceedance” of health standards, Aguayo of Xcel wrote in an email in October. “Because of this, there is no reason to sample the sediment.”

Since 2020, the issue has not been on the agenda of the county commissioners, according to County Commissioner Levy. In May 2023, Xcel held a public meeting to present on plans to address the contamination, but only five community members — two from our reporting team — showed up.

Invitations were mailed or hand-delivered to a few hundred residents who live close by. The meeting was not publicized on Boulder County’s website.

Levy said the county commissioners were “pretty disappointed with the turnout.”

Full cleanup more than a decade away

Six years after unsafe levels of contaminants were reported at the site, Xcel’s precise timeline for a full cleanup remains in question.

The EPA requires Xcel to remediate Valmont to its condition before coal ash contamination — both stopping the contamination and preventing further pollution by removing the ash or through other means.

Xcel has been in this stage since the closure at Valmont. The EPA rule says that a remedy be selected “as soon as feasible” after measures to “correct” the pollution are proposed.

“We see this everywhere,” said Russ of the Environmental Integrity Project. “Companies start the corrective action process, but they don’t select a remedy.” The group’s 2022 report, covering 265 contaminated sites around the nation, found only 38 have outlined a full cleanup plan.

At Xcel’s May meeting, the company detailed a plan to install above-ground treatment systems to extract the polluted water, remove the contaminants and possibly pump it back into the ground. Xcel expects to begin this work in late 2024.

“There’s some administrative steps we have to do to make sure we’re getting the best deal — the most cost-effective and most technically sound,” Jennifer McCarter, an environmental analyst for Xcel, said at the meeting.

While Xcel is treating the contaminated groundwater, the company also plans to remove up to 85% of the ash from the landfill, starting with the most contaminated sections, to prevent further pollution spread. According to documents submitted to the Colorado Public Utilities Commission in June 2023, Xcel estimates “pump and treat” to cost about $19 million, and ash removal to be $34.5 million. Xcel asked to delay these costs with the PUC and currently does not plan to raise rates for Colorado residents to pay for the cleanup, according to its filings.

The removed ash will be recycled in a process called “beneficial reuse” — where the ash is used to make concrete and other building materials. Xcel has contracted with a recycler in Kentucky to do this work. Xcel anticipates the removal will take 10 to 12 years — so the landfill will be majority ash-free in 2035 at the earliest.

EPA says there’s been progress at Valmont, lawsuits drive cleanup elsewhere

The U.S. EPA Region 8, serving Colorado and five other Western states, declined to make anyone available for a phone or in-person interview. In emailed responses in the spring, Richard Mylott, the office’s public affairs specialist, said the EPA has made “satisfactory progress on work to perform monitoring, investigate the nature and extent of any contamination, and to assess remedies to deal with any potential off-site contamination.”

Mylott added that Xcel “appears to be nearing proposal and selection of a remedy” to address the groundwater contamination.

On the issue of broken website links, Mylott said, “The EPA is aware that the Xcel CCR website has, at times, required many refreshes to access documents, particularly very large documents, and has raised this concern with Xcel. The website appears to have improved, but EPA will continue to monitor this to ensure the documents are publicly available as required by the CCR rule.”

In an effort to force utilities to comply with the CCR rule, advocates elsewhere have relied on civil suits.

One such lawsuit, filed by the Southern Environmental Law Center, resulted in a 2020 settlement requiring Duke Energy to remove 80 million tons of coal ash from unlined ponds across North Carolina. The effort is expected to be the largest excavation in the country.

Another SELC lawsuit in Virginia led to a new state law requiring coal ash be removed from unlined sites. A third forced the utility Georgia Power to properly dispose of most of the coal ash in its state.

Meanwhile, under a new EPA rule proposed in May 2023 to regulate old landfills, Xcel might soon be forced to monitor, and eventually clean up, the unregulated ash landfill that thus far has not undergone scrutiny. The federal coal ash rule does not currently regulate landfills that haven’t received new coal ash since 2015, a loophole that has left an estimated 500 million tons of coal ash unregulated.

Malinowski, of the county, said in the spring he was unaware of this separate old landfill at Valmont. “That’s the first I’ve heard of it, so I’ll look into it,” Malinowski said.

In Boulder, as the timeline drags on, the residents at Valmont Road feel caught in the uncertainty of not knowing when the contamination might reach their wells.

“I think it is awful. It’s something that needs to be cleaned up,” said the resident who asked to remain anonymous. They added that leaving the clean-up to Xcel makes it feel like there’s no end in sight.

“It is going to be 50 years from now,” the resident said, adding that the coal ash is “just sitting there.”

“At some point we have to do something about it.”

Borke, the beekeeper, said moving isn’t an option for his family. He feels he has the right to safe water. “They need to come up with a solution, even if it is a band-aid solution while they are planning a full remediation.”

Borke said he will continue fighting to ensure his growing family has safe water to drink.

“We aren’t going anywhere. We’re gonna be here through all of this.”