PORT-AU-PRINCE

Ten years ago, when Haiti was hit by its worst natural disaster in more than a century, the country didn’t have its own earthquake surveillance network.

It does now. The problem is, the 10 foreign-trained quake monitors who work there can’t stay in the building that houses the unit overnight because it is not earthquake resistant, and even if it were, there isn’t enough money to pay anyone to spend the night.

When the ground shakes again, they’ll have to run out of the facility’s only exit.

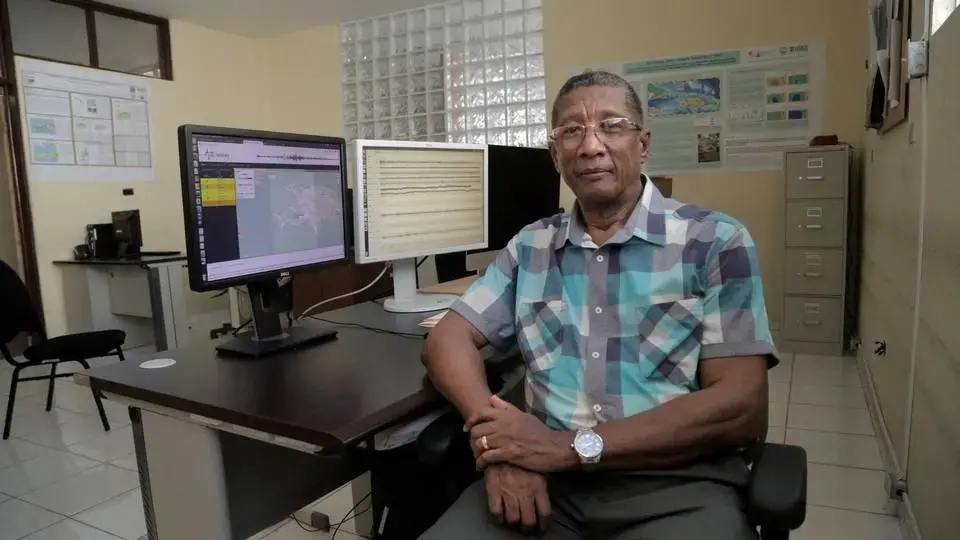

“Am I scared? Well, that’s the job. I have to do it,” said Claude Prépetit, 68, Haiti’s foremost earthquake expert and as close as the country gets to having an in-country seismologist. “The conditions are not ideal ... but we have to do it. We have an entire nation that’s waiting on us to give them information.”

Prépetit is not actually a seismologist. He’s a geologist and the director of Haiti’s Bureau of Mines and Energy, and supervises the small seismic monitoring team inside the one-story structure in the city of Delmas. The city is part of the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area that was decimated by the catastrophic magnitude 7 earthquake on Jan. 12, 2010.

Before the quake, Haiti had to consult the global U.S. Geological Survey for information on earthquakes larger than magnitude 4. Since Prépetit set up the network in 2011, Haiti now receives information broadcast via satellite from solar-powered seismic stations dotted around the country, and via internet from a network of seismometers that record tremors in real time. The seismic team analyzes the data and issues bulletins on quake occurrences and the potential for future earthquakes.

Progress, But...

The 2010 quake caused more than 100,000 structures to crumble and created enough rubble to fill five football stadiums. At the time, Haiti had no quake-resistant building codes or in-depth understanding of its vulnerability. There are four major fault lines and many secondary ones crossing the country, which sits on two tectonic plates. As the plates slowly move past one another over time, stress builds up. The Léogâne fault that caused the 2010 quake was previously unknown.

Since the devastation, there has been progress, though. There is Prépetit’s seismic surveillance network, as well as active-fault and hazard maps, tsunami evacuation routes in the northern region and the first class of students soon to graduate with a master’s degree in geoscience from the State University of Haiti in Port-au-Prince. There is also considerably more knowledge about how the country’s various soil types, when combined with the effect of an earthquake, can liquefy and cause the ground to behave like quicksand in certain regions.

But for every bit of progress, there is plenty that has not been done to prevent a repeat of the cataclysmic disaster that claimed more than 300,000 lives and left 1.5 million people injured and another 1.5 million homeless.

“We do not have a national disaster risk management plan. We do not have a national plan to reduce the seismic vulnerabilities,” Prépetit said. “There is not a plan that says it is mandatory that they do awareness in all the schools and teach them what to do before, during and after. All of these are weaknesses that we have, which means that the next earthquake, if it’s of a high magnitude, well, the damages will be considerable.”

At best, the progress has been halting, he said, pointing out that $9 million worth of earthquake-related studies approved by the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, co-chaired by former U.S. President Bill Clinton, has been collecting dust in drawers because there is no money or political will to confront the looming problem.

Nowhere is this more profound than inside Prépetit’s Seismology Technical Unit, where they recorded 301 tremors in 2019.

'It's Not Normal'

When a Miami Herald team visited in mid-November, Prépetit was the only one at work. The unit’s employees and staffers assigned to the mining bureau were home due to a countrywide lockdown, prompted by an ongoing political crisis. At the same time, the seismic station in Hinche was broken. There was no fuel for the generator, so the equipment was operating on a backup battery.

Weeks earlier, the United Nations Development Program had to cut a check for $7,500 because there was no money to pay for the satellite connection after the bill came due on Oct. 31.

“It’s not normal for a country that’s functioning, that’s doing seismic surveillance,” Prépetit said. “There should be a minimum budget. It should get a minimum of attention.”

Sophia Ulysse, who works with Prépetit in the seismic unit, said she and the other monitors do try to track quake activity from home, but “sometimes we try to connect and we can’t,” she said. “What is ideal is to have around-the-clock surveillance.”

Because the building that houses the seismic unit is not quake resistant, Ulysse said, “if an earthquake were to happen and the building isn’t able to resist, then all of the efforts we have made since Jan. 12, 2010, risks collapsing in a matter of seconds.“

Reginald DesRoches, the dean of engineering and incoming provost at Rice University in Houston, who traveled to Haiti to help after the quake, said there is no question that Prépetit and his team need adequate funding and support.

But that’s not their only challenge, said DesRoches, who is of Haitian descent and counts among his PhD students at Rice a young Haitian man who plans to return to Haiti to teach and work in seismic-resistant design.

“The biggest challenge that Haiti faces is the lack of an infrastructure and framework to enforce earthquake-resistant design standards,” he said. ”It is meaningless to have a [building] code if you have no way to enforce it. Over 90 percent of the buildings in Haiti are informal or non-engineered homes. ... It is very difficult to enforce proper construction practices.”

Prépetit agrees.

“It’s a rare engineer or person who builds differently, who uses [quake-resistant] construction techniques” in Haiti, he said. “The state doesn’t have the authority to say, ’No. I don’t agree.’ Things are being done the same way they were being done before January 12.”

While municipalities are responsible for issuing construction permits, they have neither the authority, capabilities, staff nor financial resources to enforce them or apply any of the recommendations from the various studies, Prépetit said.

After the 2010 disaster, the Haitian government estimated that more than 208,000 buildings were damaged, 105,000 were destroyed and 44 public buildings had collapsed, including the National Palace, the Parliament and the Supreme Court.

Since then, Haiti has had four presidents and seven prime ministers. Prépetit has had contact with them all, he said, as well as the various interior ministers whose job it is to oversee the government’s management of disaster risks.

None of them, he said, has really tried to focus on helping Haiti become earthquake-ready — or as ready as the small nation can be.

“I’ve never seen any will manifested from them to say that they consider this to be an emergency and it should be given the proper budget,” he said. ”It is the institutions that are concerned. They each have tried to do a little something. That’s why we have the progress that we have today.

“It’s like you have a band, there are several musicians, everyone is playing his own part but there is no maestro,” he said. “We don’t know where we are going.”

'We Have no Means'

The Bureau of Mines and Energy, which oversees geology, mining and energy as well as earthquake surveillance, has an annual budget of just 60,000,000 gourdes — or $617,852. The amount represents just 0.04 percent of the country’s national budget, and 86 percent of it goes into salaries, Prépetit said.

“It’s 14 percent [left over] for us to function; to purchase vehicles, to purchase fuel, to purchase water, to purchase paper, ink cartridges,” Prépetit said. “We have no means.”

Money is also needed for the internet, and to replace the solar panels and batteries that are often stolen from the seismic stations around the country.

“What we do here is a Haitian effort,” he said. ‘We have a lot of will. We have the stations, we have donations, we’ve tried to install the system, but we don’t have a budget or program to really attack the problem.”

In recent years, some foreign donors have tried to provide funds to help support Prépetit’s work and help strengthen Haiti’s response structures. But the government also has to do its part, donors say.

“It remains critical to advocate for dedicated national budgetary allocations for both prevention and response capacities, and to ensure that risk awareness is mainstreamed throughout national planning processes,” said Stephanie Ziebell, the United Nations Development Program’s deputy resident representative. “This includes ensuring that those responsible for essential monitoring and analysis have the appropriate tools and facilities to enable their work.”

'People Got on Their Knees'

A tall, lean man, Prépetit considers it his duty to do what he can, even with all of the challenges. Twice he could have died on Jan. 12. First, the building at the Université GOC Haiti where he taught a construction course collapsed. Luckily for him, he said, the course had been canceled that semester.

His office at the bureau of mines, which he left before the quake struck, also buckled.

“I am conscious of the fact that I am living in a country that is very vulnerable,” he said. “I know that if we have an earthquake in a country that is very vulnerable, a lot of my fellow countrymen will die. And I believe that it is through education that we have to reduce vulnerability.”

While the death estimates from the 2010 quake toll have varied — the U.N. cites 220,000; the Haitian government, 316,000 — one thing is clear: Many people died not just because of poor construction but because of ignorance.

“The earth shook and people got on their knees. They thought it was God shaking the earth. They did not understand what was happening,” Prépetit said. “There were people who were in the streets, the ground was shaking and they ran inside a house. The houses fell on them.”

Prépetit said he does have a plan for an earthquake-resistant facility to work out of. He also has a spot, an empty space in the yard of the current facility. But again, there is no money.

“A seismic surveillance system needs to operate around the clock. There should be dormitories so that even if the office closes at 4 p.m., there are personnel who remain on site throughout the night to monitor because earthquakes don’t have schedules,” he said.

Haiti was reminded of this in October 2018 when a relatively moderate 5.9 temblor struck the northwest city of Port-de-Paix and its surrounding towns. Seventeen people died, hundreds more were injured, and schools and homes collapsed. Studies have shown that the region is due to experience a major magnitude 7 or stronger quake.

“We are not yet ready,” Prépetit said. “All of the towns that were close to the epicenter were affected by a very moderate earthquake. ... If what we anticipate were to happen, the devastation would be more considerable than what happened in Port-au-Prince in 2010.”

And should another quake strike Port-au-Prince while he’s at work? Well, there is the evacuation plan. But the plan, he concedes, depends on the magnitude and where it catches him at the moment.

“If I am in my office, there is nothing else that I can do other than go under my desk, wait until the earthquake is over and get out,” he said.

And if it’s a powerful one like the one that struck 10 years ago?

“There would be a big risk that we would be buried underneath the rubble of this building.”