This article was also featured in Global Post.

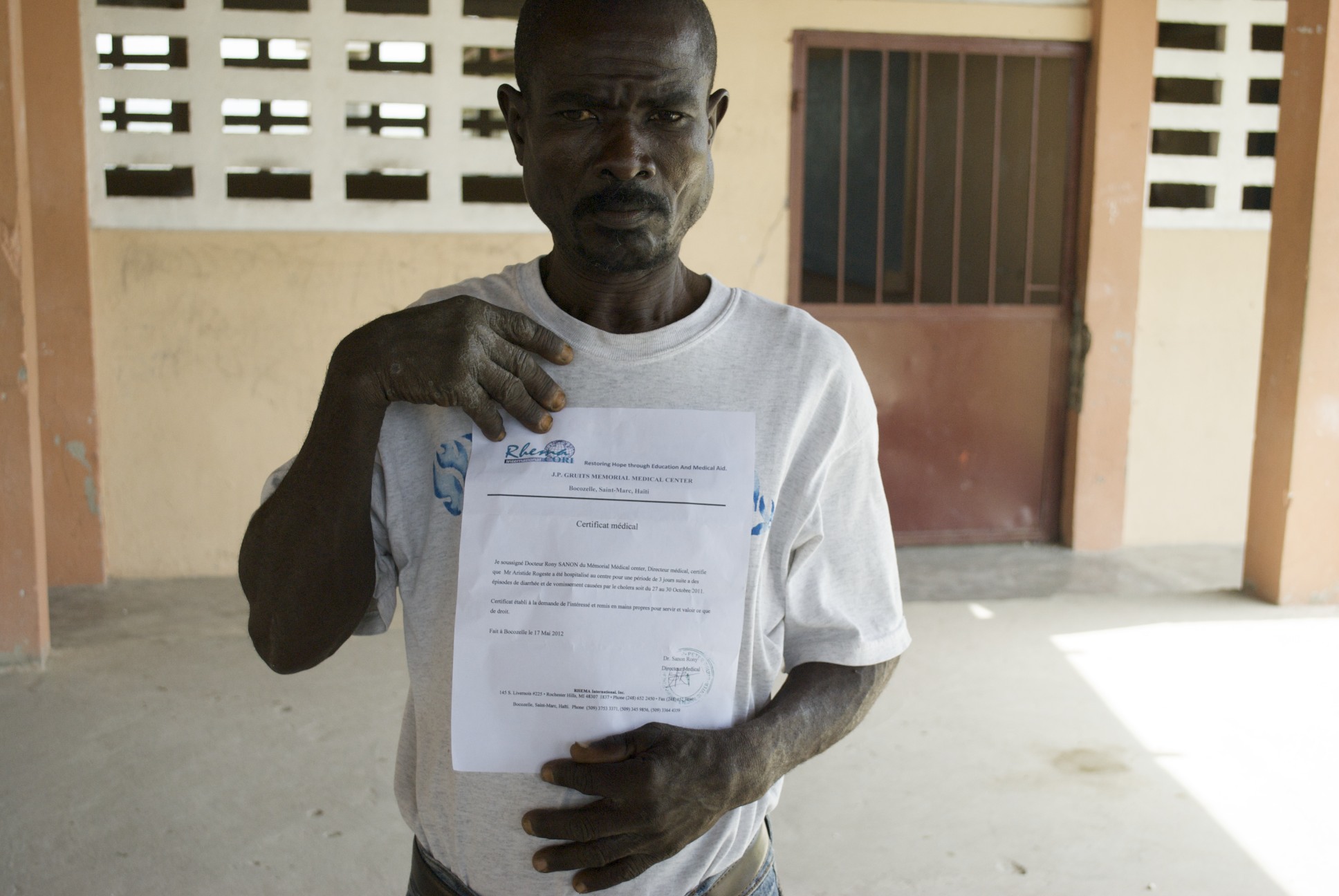

Is it possible for Aristide Mojes, a short Haitian man with grizzled hair, to win a lawsuit against the United Nations and MINUSTAH, the UN peacekeeping forces in his country? Mojes, a cholera victim who spent five days in the hospital to survive the diarrheal bacterium, and the UN, a conglomeration of 193 countries that will spend $793 million on MINUSTAH this year alone, are a mismatch.

Mojes is not alone. With over 7,000 dead and annual epidemics after the rainy season, more than 15,000 cholera-affected Haitians joined together to file a legal complaint against the UN on November 3, 2011. The case asserts that UN troops from Nepal brought cholera to Haiti when their sewage contaminated a tributary of the Artibonite River in October 2010. Asked what he hopes for from the case, Mojes said, "Make the damages better."

Now, seven months after the complaint was filed, their case sits idle because the UN denies responsibility for bringing cholera to the country. So, where will Mojes and his fellow Haitians go now? When it comes to the largest international organization in the world, one built on the shoulders of almost every country in the world, there is no appeals court: there is no higher governing body.

"In many ways, cholera is more a justice issue than a medical issue. You don't get cholera unless you are poor – unless you don't have access to clean water" said Brian Concannon, Director of the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH).

Clean water is not easy to find in Haiti, which ranked dead last out of 147 countries in the Water Poverty Index completed by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. IJDH works with Mario Joseph of the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI), to reach out to victims of cholera in Haiti and build their case. In the legal vernacular of the case, IJDH and BAI accuse the UN of negligence, gross negligence, recklessness, and gross indifference.

The cause of the stagnation is the Status of Forces Agreement, signed between UN forces and its host nation, which shields the UN from legal accusations. The formal caveat in the Status of Forces Agreement is a Standing Claims Commission to hear the cases of victims of wrongdoing (it works for everything from cholera to car wrecks) - but the UN must approve the commission. "The UN has never responded fairly to accusations of large-scale wrongdoing," says Concannon, because the UN has never opened a standing claims commission in any country, ever. "Because there is no claims commission it is hard to work because you have victims but you cannot go through the process," said Joseph.

"There are a couple ways around it," says Concannon. "One is to try and get into national court – the other is to apply public pressure on the UN." In regards to public pressure, Concannon and Joseph may just get the boost they need. Award-winning directors David Darg and Bryn Mooser created "Baseball in the Time of Cholera," which won a Special Jury Mention at the Tribeca Film Festival and appeared online July 12, 2012.

After living in Haiti for the years following the earthquake, Darg and Mooser witnessed firsthand the impact of cholera on the tenuous stability of the country. Their film chronicles the hope and camaraderie Joseph Alvyns, a young Haitian, develops with his little league baseball team (the only one in Haiti) before he loses his mother to cholera. The film culminates in a call to action to support the case against the UN and features interviews with Concannon and Joseph.

While there is great opportunity for public pressure through this compelling film, the road for viral advocacy is laden with pitfalls and naysayers – most recently encapsulated by the Kony2012 campaign. Furthermore, while "Baseball in the Time of Cholera" hopes to sway public pressure in favor of the Haitian plaintiffs, its capacity to place pressure on the UN does not necessarily extend past this case. For Mojes and his fellow Haitians to rely on a viral advocacy campaign raises questions as to whether the current system of international justice is one where successful cases are determined by the social networking prowess of their supporters.

Concannon's second option, the trial of the case in the formal legal system of Haiti or the United States, is equally problematic. The Haitian delegation can cite scientific studies performed by the Centers for Disease Control and epidemiologists to support their case, while the UN may counter with scientific studies by the University of Maryland that suggest cholera was a natural part of Haiti's ecosystem long before the outbreak. Courtroom posturing aside, if the case wins, what happens then? In the last few decades groups like the International Law Association pushed for more stringent structures to encourage accountability, but these were never realized.

There is no formal enforcement or monitoring system for a case like this. There is no precedent that indicates what a victory in national court actually implies in terms of a UN response. But then again, there has never been a case with so many plaintiffs. Finally, if the UN does institute a Standing Claims Commission, the fate of men like Aristide Mojes returns to the UN system.

Mario Joseph worries that Haitians will not have their voices heard. "It's not only about what happened," he says. "There is a lack of justice."

- Document