As a young man, Purnendu Goswami was a proud Hindu nationalist who went to extremes to promote his beliefs. Now 49, he describes himself as a humanist who practices “radical love."

Wreathed in flowers and colorful banners, the alleyways near the renowned Banke Bihari Temple in the northern Indian city of Vrindavan come alive every summer during the Narasimha Jayanti festival.

Hundreds of devotees join in processions to celebrate the half-man-half-lion incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu.

“It was an intimate festival for us,” Purnendu Goswami said. “It brought meaning to my life and made me more religious.”

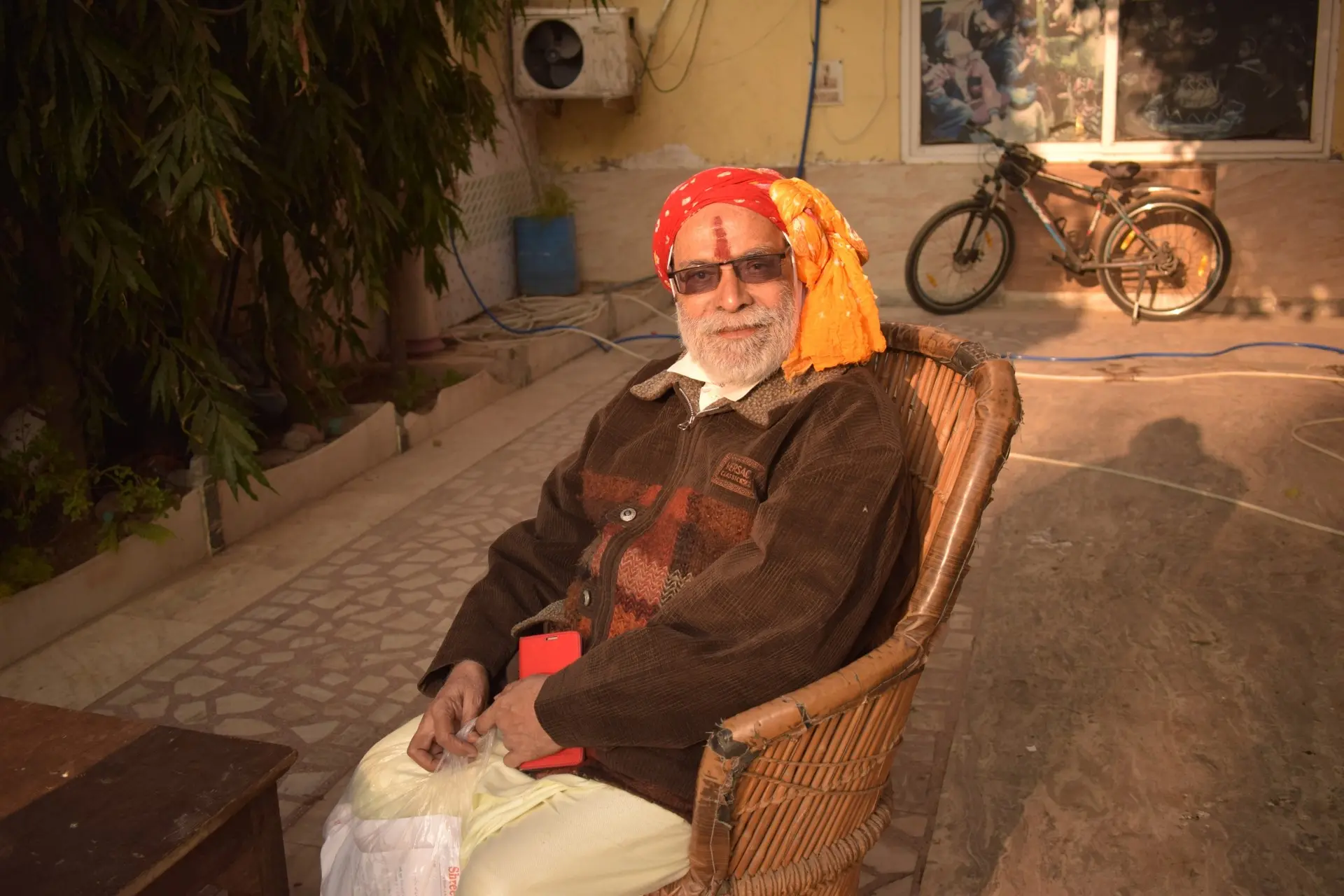

Purnendu Goswami, 49, grew up near the Banke Bihari Temple — considered a major Hindu pilgrimage center. More than 6,000 temples in this town by the banks of the River Yamuna are dedicated to the Hindu God Krishna.

But today, Purnendu Goswami, who was once proud of being not only Hindu, but a firebrand Hindu nationalist — has rejected his ties to Hindu extremism. He said a series of personal experiences led him to believe in “radical love.”

“As an upper caste Hindu family, we felt our biggest contribution was that we were religious,” Purnendu Goswami said. He visited temples daily, offered prayers and sang devotional songs.

Goswami’s 80-year-old father, Balakram Goswami, is a prominent religious narrator in Vrindavan. He sings hymns and recites prayers as part of his commitment to spreading the words and deeds of Ram and other Hindu deities.

Purnendu Goswami and his two brothers would join their father on his religious pilgrimages across India. They attracted hundreds of followers during their travels.

Like many pious Hindus, they revered the temple town of Ayodhya as the birthplace of their God Ram — one of the most sacred in the Hindu pantheon of deities. Every year, they would make their annual pilgrimage to Ayodhya, bathe in the holy Sarayu River and meet with religious leaders.

“Our education was mostly scripture-based,” Purnendu Goswami said. “But in Ayodhya, we learnt a lot from priest-narrators during religious storytelling at temples and monasteries.”

Religion and politics, 'intertwined'

Purnendu Goswami’s commitment to the Hindu way of life started changing from the late 1980s.

Purnendu Goswami and his older brother, Balendu Goswami, joined the Ram Janmabhoomi movement — a campaign spearheaded by India’s current ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, to demolish a 16th century mosque in Ayodhya, the Babri Masjid, and replace it with a temple.

Hindu nationalists claimed the mosque stood on the specific ground they believed to be the birthplace of the God Ram, so it was a mark of humiliation on India’s Hindu past.

“Ayodhya was a political agenda,” said Purnendu Goswami, who joined thousands of Hindu nationalists in campaigning for a new Ram temple to be built exactly where the Babri Mosque stood. He said it became a question of their ego, pride and self-respect.

At rallies and ritual congregations in Vrindavan, young Purnendu Goswami — wearing a starched dhoti (sarong-like garment) and saffron scarf — insisted that only a Hindu government could “emancipate Hindus.”

“Religion and politics were getting closely intertwined,” he said. “I felt I would gain power if I joined the movement and if I fanned the communal flames.”

On Dec. 3, 1992, he joined a group of 50 other Hindu nationalists who set out from Vrindavan to demolish the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya. They chanted fiery slogans.

But half a mile down the road from where they left, Purnendu Goswami was arrested and sent to jail.

A few days later, on Dec. 6, thousands of Hindu extremists set upon the mosque in Ayodhya and demolished it using hammers, pickaxes, crowbars and iron rods. In the riots that followed across the country, more than 2,000 people were killed — mostly Muslims.

Purnendu Goswami said there was nothing in his heart back then besides hate and fanaticism.

“If I reached Ayodhya, I could have killed people or become a martyr for the movement.”

Purnendu Goswami said he nursed an intense hatred toward Muslims. He saw them as aggressors and wanted them to be thrown out of the country and their identities to be erased.

In jail, he remembers being treated like a celebrity for doing something great for their god, country and religion. Upon his release, Purnendu Goswami was garlanded for his heroism.

“I didn’t have a shred of remorse,” he said. “I felt the demolition was a victory for Hindus.”

Growing Hindu nationalist zeal

In the years that followed, Purnendu Goswami’s Hindu nationalist zeal grew.

His family decided to build a large ashram in Vrindavan to draw prominent political and religious leaders, and Purnendu Goswami started thinking of ways to make inroads into politics.

In 1997, they built a cave on the ashram premises into which Purnendu Goswami’s older brother Balendu Goswami retreated for three years and 108 days to contemplate Hinduism.

“The cave experiment was essentially a career investment for us,” Purnendu Goswami said. “We wanted to make religion profitable and become famous.”

In December 2000, when Balendu Goswami emerged from the cave, the brothers’ fame grew. Devotees touched his feet and thought he was blessed with “the powers of divination.”

The brothers started getting invited to religious events in India and abroad.

At the ashram, Purnendu Goswami started engaging with people from different backgrounds and faith leanings, and their work broadened to include yoga, meditation and Ayurveda.

A turn toward ‘radical love’

Around then, Purnendu Goswami also lost his sister in a fatal car accident that made him question justice and God's plans.

“Earlier, we would justify everything as God's will,” Purnendu Goswami said. “But both suffering and new experiences not only changed our worldview but made us question everything.”

Purnendu Goswami started thinking more critically.

"There was a lot of questioning internally," he said. "I started thinking if the gods we worshiped, the religious discourses we delivered and the rituals we performed were real or imagined."

"When those questions grew louder in my head," he said, "I was able to break free of my religious bigotry and prejudices."

The turn to atheism "felt natural" to him.

The internal changes also sparked a transformation in his surroundings — the Goswami brothers stopped all scripture classes and rituals and shut down a shelter for cows that are considered holy animals by religious Hindus.

In its place, they opened a school for poor and disadvantaged children at the ashram.

But the turn to atheism also drew disfavor from Vrindavan’s religious community.

“This was quite shocking for us,” said Lalit Sharma, Purnendu Goswami’s childhood friend. “Their exposure to individualistic culture abroad possibly weakened their religious ties.”

In 2016, when Purnendu Goswami and his brother organized an atheist meeting at their ashram, the place was ransacked, violence erupted and town authorities imposed a curfew.

The threats and social alienation from Vrindavan's religious community grew over the years. All this spurred Purnendu Goswami to rethink his “radical atheism.”

“Fanaticism is all about aggression,” he said. “Whether you believe in God or not, you can’t turn your faith into a commercial project.”

Purnendu Goswami felt his atheism came, not from a place of love, but from anger and aggression.

Today, he’s turned away from both religion and atheism. Purnendu Goswami said he’s a humanist — someone committed to helping people regardless of their religion, caste or gender — who’s made “radical love” the basis of his life’s work.

Purnendu Goswami has poured himself into revamping his ashram school for underprivileged children and, during the pandemic, he helped deliver food aid to thousands of Vrindavan’s poor.

He is now committed more than ever to his humanism amid the growing religious polarization and communal tensions in India.

The elder Goswami, who’s still very religious, does not invite his son to join in any rituals or prayers. He said he respects his son’s personal transformation and views on religion.

“If you need God,” Balakram Goswami said, “then God exists, and if you don’t he does not exist.”