Editor's Note: this story was published by Malaysiakini in English, Malay, and Chinese.

Deforestation has led to more human-wildlife conflict, pushing wildlife to the brink of extinction.

Since hearing his 15-year-old brother’s screams of anguish when trampled to death by an elephant, Borhan Yok Manin, 24, suffered sleepless nights.

Early this year, Borhan, his brother Andy and their relative Faizul Yok Tong had ventured into a forested area near their village in Kampung Tual, Pos Sinderut, near Sungai Koyan, Pahang, to look for petai.

The Orang Asli youth from the Semai tribe had done this countless times before.

Andy, a Form Four student, told his mother he was delaying returning to his boarding school to help the family make some extra money through foraging in the forest.

The decision cost him his life.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

On Jan 9, Borhan said, the youths came across the bull elephant which had been roaming in that area for several weeks. When the trio turned to flee, Andy tripped and fell.

“I heard him scream “Ma!” but we could not save him,” Borhan recalled.

It would be an hour until villagers felt it was safe to return to the scene. By then, Andy was dead. There was a gaping wound in the chest area of his mangled remains, believed to be inflicted by the elephant’s tusk.

Their mother, Normah Isa, could barely utter Andy’s name, when met days after his death. She remembers him as a bright, cheerful and helpful boy.

He was the family’s pride and his parents had hoped he would be the first of their children to complete schooling and reach greater heights.

“When we informed his school he had died, all his teachers cried,” his father, Yok Manin Yok Chik, said, holding back tears.

This was the same elephant which is believed to have trampled a woman in Kampung Simoi, another Semai village separated from Pos Sinderut by dense forest less than a month before.

The Wildlife and National Parks Department of Peninsular Malaysia (Perhilitan) sent a team to track down the elephant, and after a week or so, the rangers concluded it had returned to the Ulu Jelai Forest Reserve.

But it returned to Kampung Simoi just weeks after, and was finally captured on Feb 18.

Its home, the Ulu Jelai Forest Reserve is a known habitat for Asian elephants - an endangered species according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with about 1,500 left in Malaysian forests.

Forest clearings

Yok Ek, the village chief of Kampung Tual, said this was the first time an elephant was spotted near the village in at least five generations, but herds have been spotted in Kampung Simoi since forest clearings started in the Ulu Jelai Forest Reserve.

These are satellite images of Ulu Jelai Forest Reserve, near Pos Betau where a woman was trampled to death by an elephant, before and after the forest clearing. The same elephant is believed to have trampled Andy.

The Semai villagers near Ulu Jelai Forest Reserve are not alone in their plight.

Increasing human-wildlife conflict does not only affect indigenous communities living within permanent forest reserves.

In parts of Johor, a wild elephant had entered a prison, while several incidents where elephants were spotted in housing areas were reported in the vicinity. In Pahang last May, a plantation worker was trampled to death by an elephant.

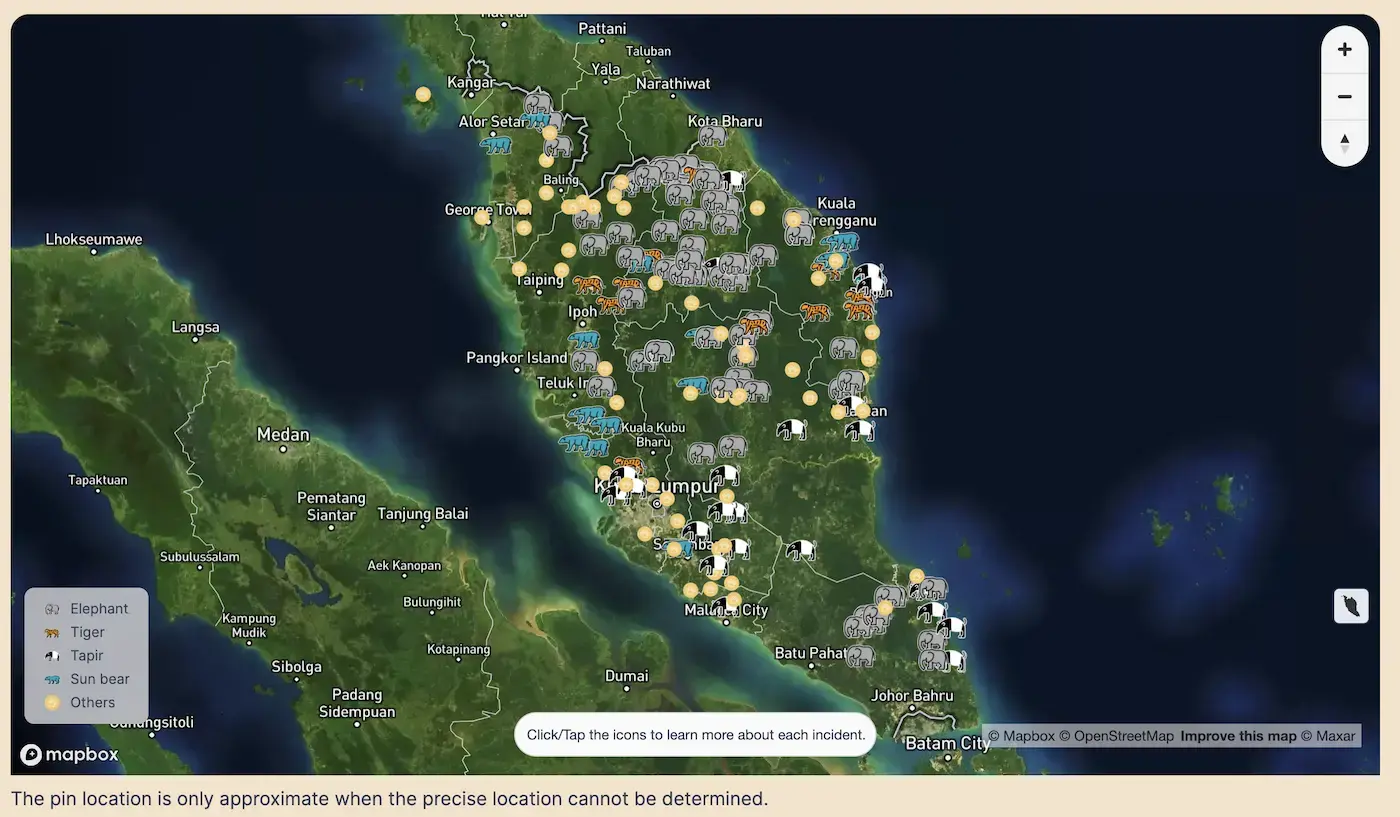

Below is a map showing human-wildlife conflict from January 2020 to February 2023. The data is based on media monitoring of Bahasa Malaysia and English language news media and social media in Peninsular Malaysia, by Malaysiakini.

How to engage with the map?

This map shows the location of human-wildlife conflict from January 2020 to February 2023, based on Malaysiakini’s media monitoring. Click or tap on the data points and read each description. You can also filter the data by different categories.

Visit Malaysiakini to interact with the map.

Data from Perhilitan show human-elephant conflict is indeed on the rise, but it is not just elephants.

Habitat loss has been cited as the main threat for many endangered wildlife species in Malaysia, especially for the group of charismatic wildlife species known as the Big 5 Malaysian Animals: the Malayan tiger, the Asian elephant, the seladang, the Malayan tapir and the Sumatran rhinoceros.

In 2019, the last living Sumatran rhino in Malaysia - Iman - died in captivity. Conservationist fear without more urgent action, the days of the remaining four are also numbered.

In fact, the extinction process is already underway.

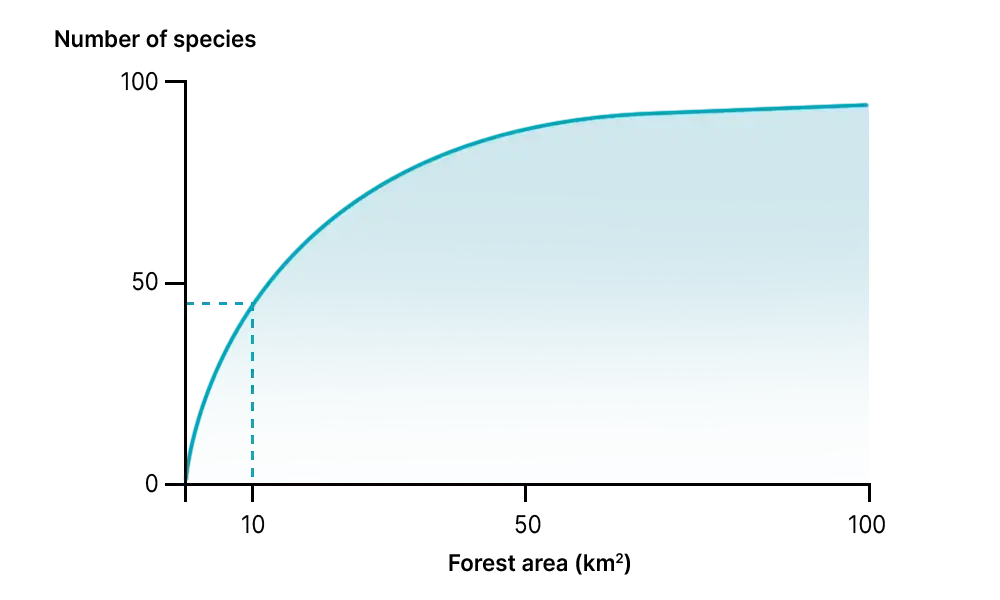

John Payne, a veteran wildlife conservationist, says that if 50 percent of habitat loss occurs, 10 percent of the wildlife population is expected to be lost to extinction.

According to him, it may take a long time for the last of the species to die, but the process of extinction begins as habitat is lost, because there is a limit to how many reproducing individuals an area can sustain.

“The main message from this graph (below) is that there is a limit to how many species can be sustained within a given area,” he wrote in a journal article in 2021, discussing how to conserve Malaysia’s endangered mammals.

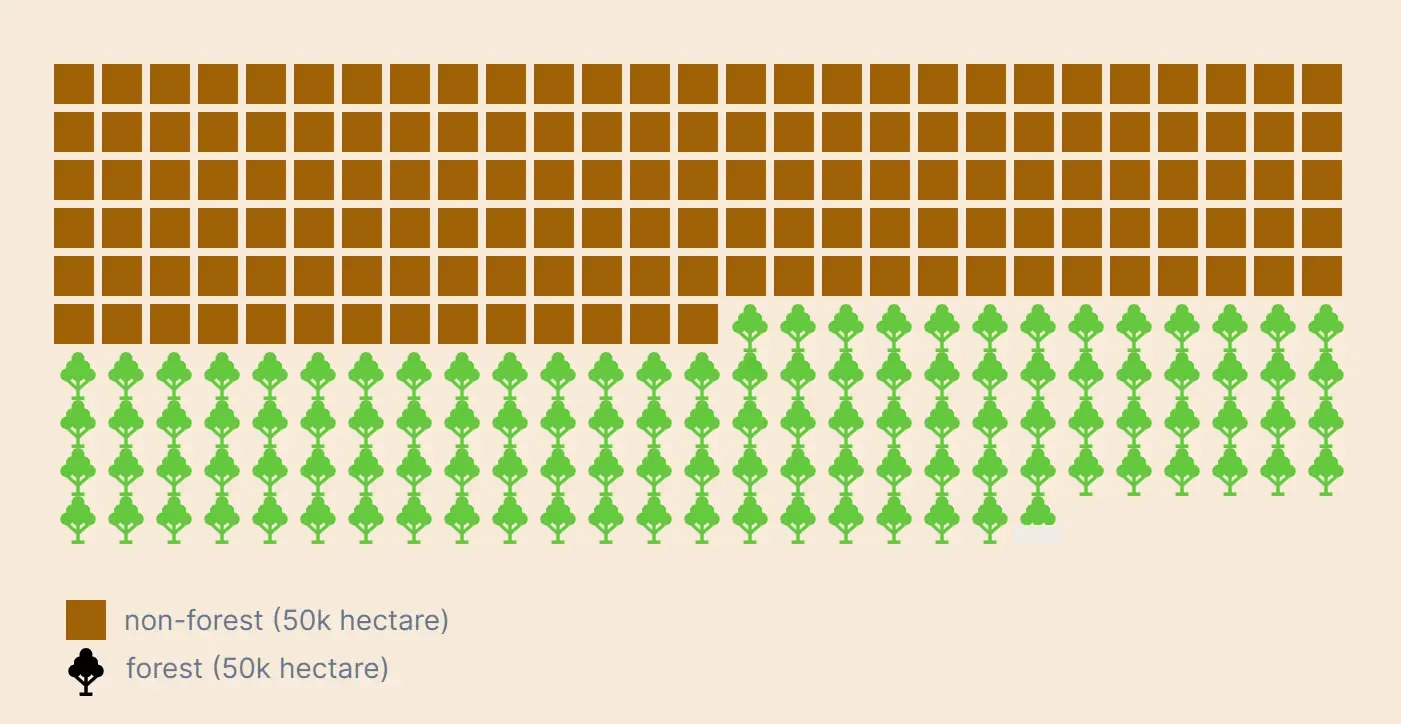

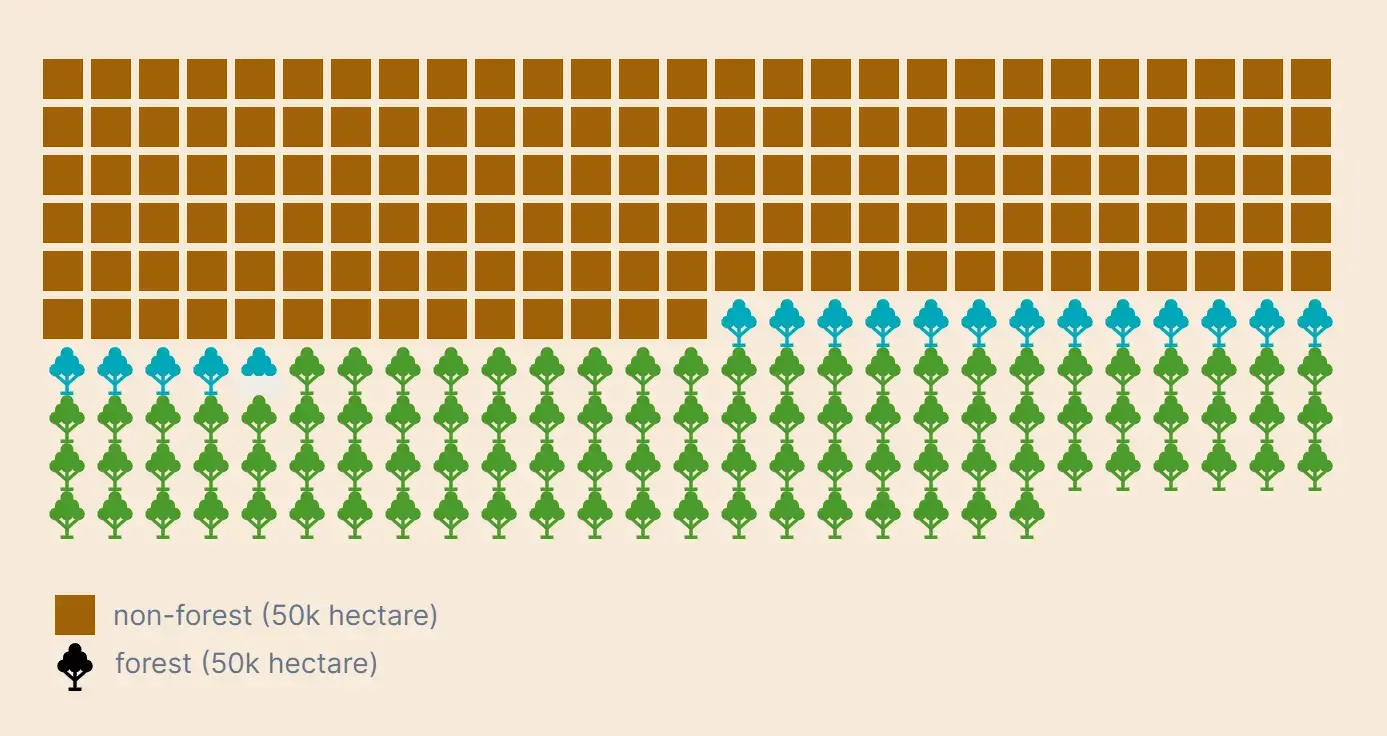

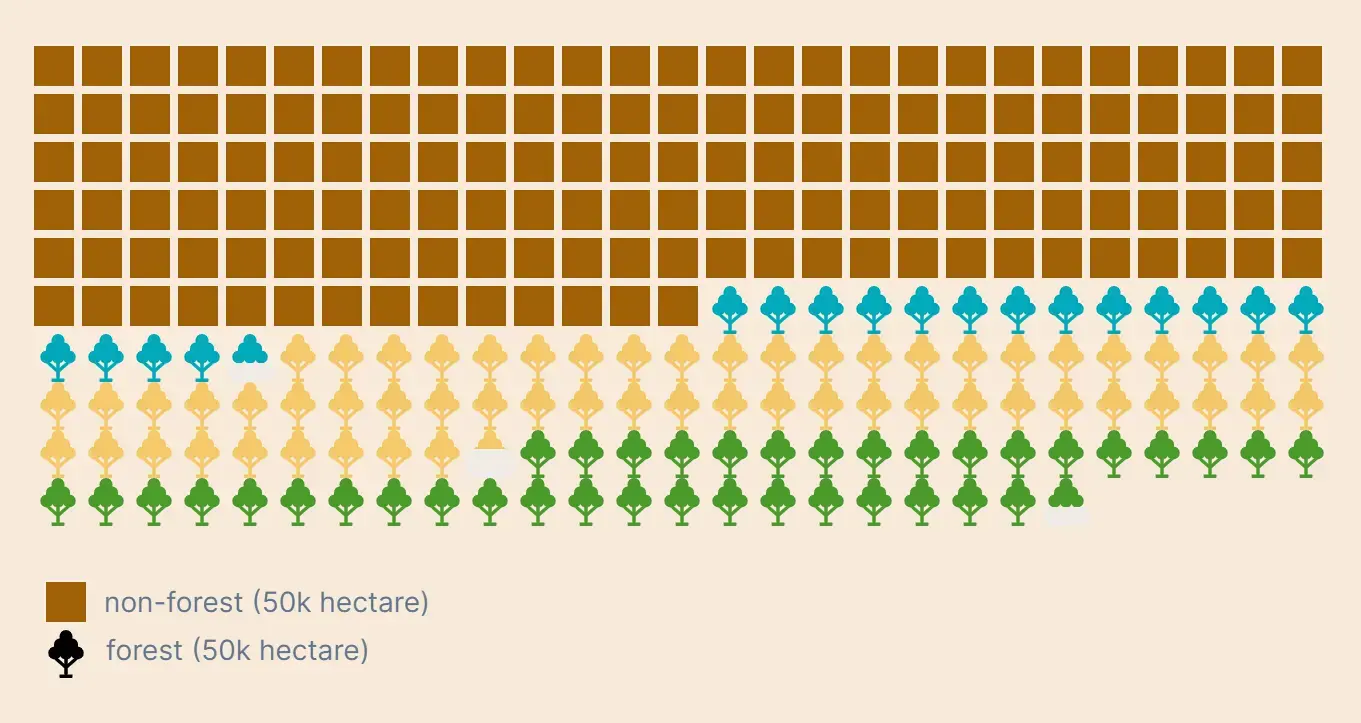

From 1954 to 2000, Malaysia has lost 37 percent of natural forest cover from 9.5 million hectares to six million hectares, based on official data. Since then, at least 2.7 million hectares of primary forest has been lost, according to the Global Forest Watch.

On paper, about half of the country is still covered in forest. On the ground, however, the reality is starkly different.

Contrary to the general perception, not all parts of the permanent forest reserve are virgin forest meant to be protected against clearing. In fact, logging in forest reserves can be completely legal. And it doesn’t just stop at logging.

Forest…but not really

Believe it or not, this is the inside of a permanent forest reserve - the Segari Melintang Forest Reserve in Perak.

When Malaysiakini visited this coastal forest in 2020, this portion of the “forest reserve” comprised quarries.

Other parts were used by the local council as a landfill while logging activities were also underway, all of them legal.

This is because those parts of the forest reserve are located in the “production forest” category.

Under the law, this portion of the forest can be approved for extraction, not just for logging but for other activities including mining and agriculture.

What this practically means is that an area which is totally cleared, like the quarry in Segari Melintang, is on paper still considered a forest, making up the 44 percent of Peninsular Malaysia which is still “forested”.

How much of the permanent forest reserve in Peninsular Malaysia is actually protected forest?

On paper, a total 5.73 million hectare or about 44 percent of Peninsular Malaysia is “forest”.

But of that, only 84 percent is Permanent Forest Reserve. That is 4.85 million hectares. The rest are state or private-owned forests, and other reserves.

And of the Permanent Forest Reserve, about 61 percent are ”production forest”, leaving 1.93 million hectares protected. This is 14 percent of Peninsular Malaysia - a far cry from the 44 percent considered “forest” on paper.

“When the forest is converted into other usage, it loses its ecological functions.

“Even as a plantation, wildlife may not be able to cross from one side to the other, and they would not be able to find the kind of food as in the forest,” said environmentalist and Sahabat Alam Malaysia field officer Meor Razak Meor Abdul Rahman.

And while logging often gets a bad reputation and is blamed for habitat loss, Meor Razak said it is creating mines, quarries and monocrop plantations in forested areas that cause the most damage.

This is because instead of logging concessions, where timber is selectively logged to ensure sustainability, areas approved for mines, quarries and forest plantations go through clear felling.

This means the area of the forest is logged clean -- a practice known colloquially as ‘cuci mangkuk’ (or ‘cleaning the bowl’).

This destroys the ecological nature of the forest, not only depriving wildlife of food but also disrupting their natural behaviours.

Routes passed down for generations

Conservationist Ahmad Zafir Abdul Wahab has been studying large mammals, including elephants, for 20 years. He said while some may argue that monocrop forest plantations simply replace one type of timber for another, they actually destroy wildlife corridors and habitats and cause forest fragmentations. This means they turn large forest complexes into disparate smaller islands.

The Habitat Foundation programme director said plantation owners often try to safeguard their crops from wildlife by setting up fences or trenches around the corridors. It is an expensive exercise, costing tens of millions of ringgit at one time.

Sometimes, wildlife just need to pass through the area to get to another side of the forest complex. Setting up fences or trenches may disrupt this and cause them to find other routes, and potentially cause more conflict with humans.

He said wildlife pass down information on roaming routes through generations. For example, a calf travelling with a herd would retrace its steps when it is older and continue roaming this path as an adult.

Elephants love eating grass, he said, so don’t normally enter a mature plantation just to raid its crops.

"But elephants may want to pass through to get to a salt lick on the other side of the plantation, in another forest complex, through a route which they have used for generations. And the plantation is now in their way."

The Habitat Foundation programme director

Ahmad Zafir Abdul Wahab

While villagers and farmers who face conflict with elephants might be happy with translocation of elephants after a conflict happens, translocations may not always lead to happy endings. Some elephants will try to return to their known range, causing more conflict along the way.

On various occasions, those facing constant elephant raids may also take matters into their own hands.

In his years in the field, Ahmad Zafir has known of incidents where villagers have set up harmful traps or poisoned the endangered animals.

In May 2021, for example, two elephants were found dead at a vegetable farm in Kluang, Johor, believed to have been poisoned. According to news reports, they had consumed grass sprayed with herbicides.

In the period of Malaysiakini’s media monitoring, six wild elephants died after coming in contact with humans in Peninsular Malaysia. Most as roadkill.

Expressways cutting across forest reserves and wildlife corridors present a real threat to endangered wildlife.

In the same period of monitoring, there were 50 incidents of roadkill involving wildlife, many of them endangered species. Many incidents go unreported in news or social media.

From 2015 to 2019, Perhilitan reported a total of 2,055 wildlife deaths due to roadkill.

This includes the Malayan sun bear, a species with only 500 left in the wild, and Malayan tapir, of which only 1,500 are estimated to be living in the wild.

Why did the tapir cross the road?

For a while, there was the assumption that there is an abundance of Malayan tapirs living in the wild. Actually, at the time, there was just not enough research to know how many there were.

Mohd Sanusi Mohamed field research in the Krau Wildlife Reserve in 2002, with the Copenhagen Zoo (Malaysia branch), among others, helped provide an estimate of the population size. It was then that it was acknowledged that the gentle herbivores were already endangered.

Today, he said, among the biggest threats to the species’ survival are vehicle collisions. But there is still not enough research to know why tapirs are crossing the road.

“The common hypothesis is that they’re doing so because there is not enough food in the forest, inter and intra disturbance, low mating opportunities and access to saltlick. This is due to land use changes. “But we don’t really know for sure until we truly observe the movement of individual tapirs crossing roads,” he said.

Sanusi said one possible reason is the carrying capacity of a forest complex, which has become smaller due to forest fragmentation.

Imagine this large area is a large forest complex

When parts of it become something else - a quarry, a plantation, build homes or build a road, for example - the forest is cut up into smaller fragments.

The wildlife living in each fragment will now have to rely on this patch of forest they live in for everything, be it food, minerals or mates.

But each species has its inbuilt roaming needs, like a tapir which needs 12 to 16 square kilometres per individual, or a Malayan tiger which roams for up to 300 square km.

Naturally lone rangers, in large forest complexes, these mammals just roam away from each other unless mating or rearing their young. When a road comes between one forest complex and the other, wildlife, including the poorly-sighted tapirs, risk becoming roadkill when they try to get to the other side.

Forest degradation, which happens when large areas of forest are converted, could also change the land acidity. This in turn affects the type of plants that can grow.

So it could be that the 300-plus plants which are known to be favoured by tapirs only grow on one side of the road, and not the other, Sanusi said.

He also speculated that the tapirs leaving forest complexes might be older tapirs, which find their roaming areas colliding with younger tapirs. Having lost the territorial battle, it heads out to find other patches of forest.

“There are many theories, but we won’t know for sure until we conduct research about roadkill. One of the methods is to capture and collar a few tapirs and follow them. This is an ongoing project in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife,” he said.

Are wildlife viaducts the solution?

As wildlife roadkill receives more spotlight, many have urged more wildlife viaducts and linkages between isolated forests, to allow them to cross safely.

But researchers who have studied the existing viaducts say without constant policing, these can be “death traps”, leading endangered wildlife straight to waiting poachers.

They also need constant maintenance, including enriching the forested areas leading to it, to encourage the wildlife to use the viaducts instead of crossing the expressways. This requires large financial commitments.

“If you go to one of the viaducts now, you’ll actually find it is more commonly used by villagers, so that might deter wildlife, as well,” Sanusi said.

Further, other researchers note, the viaducts can be rendered a waste of public funds if the forest complexes along the expressway continue to be cleared.

Isolated too long

Roads and plantations fragmenting forests also cause other issues for wildlife, said Dr Donny Yawah, a veterinarian specialising in wildlife, including the tapir.

It simply makes it harder for wildlife - especially large, solitary animals like the tapir, sun bear and tiger, to find each other and mate, he said.

Happily for the tapir, he said, there is some evidence they are still able to do so in fragmented forests. But even this depends on whether they can continue to get enough food and minerals.

There is another reason why Yawah is hopeful. In his experience doing post-mortem on Malayan tapirs, he has never encountered any female tapir with “reproductive pathological lesion”.

In layman terms, these are cysts which develop in the female mammal - including humans - if they do not breed. These cysts make it harder for them to conceive. So even if the males and females mate in the wild, they may not be able to produce offspring.

This was a hard lesson learnt from Kertam and Iman, the last of the male and female Sumatran rhinoceros in Malaysia.

Their eventual extinction from Malaysian forests came as a shock to many, but veteran conservationist Payne, who was on the forefront in efforts to conserve the species in the country, long saw the writing on the wall.

By the time greater efforts were made to tackle habitat loss and poaching, to prevent the extinction of the rhinoceros, there were too few rhinos still alive, anywhere in the world, to sustain a breeding population.

They weren’t even able to breed when brought together in captivity, because most females were suffering from reproductive pathology, brought on by never being pregnant. This is a result of there being too few males as well as too few females remaining

When Iman was captured in 2014, her uterus contained massive leiomyoma tumours, also known as fibroids. In other words, it was just too late.

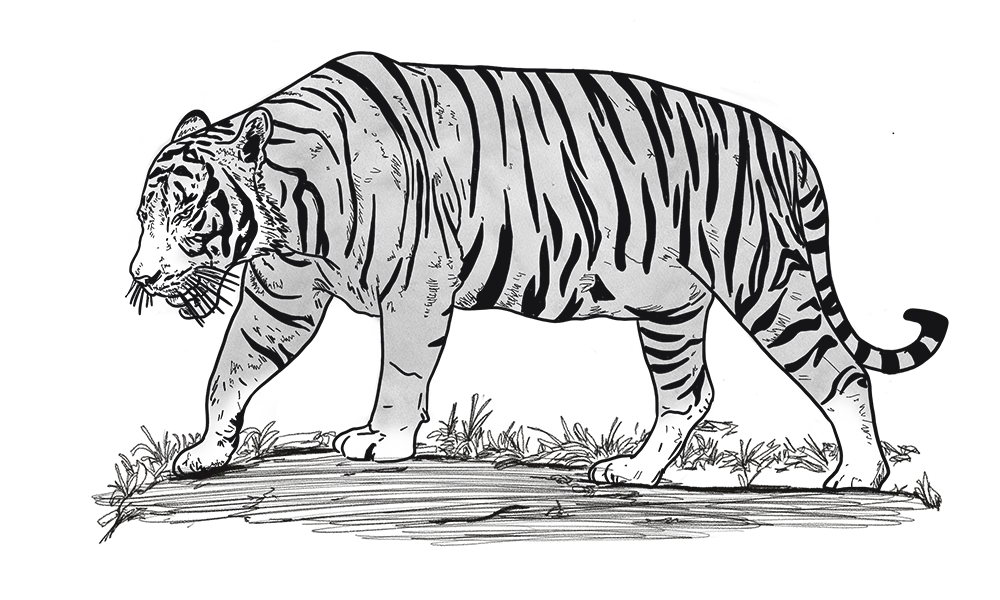

Will this story repeat for Malaysia’s national symbol - the Malayan tiger?

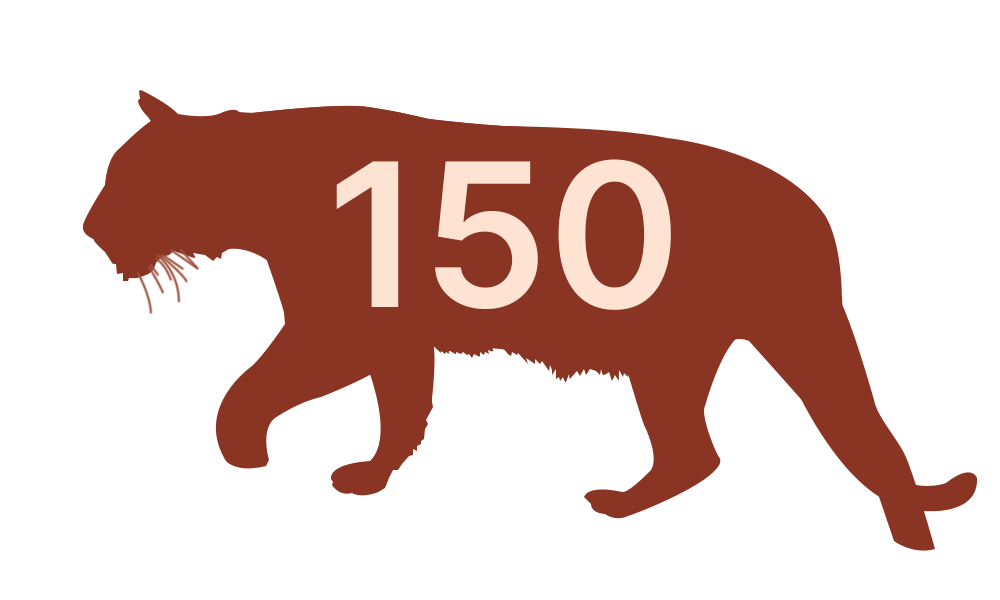

From the 1950s to today, the number of Malayan tigers in the wild has dwindled from the thousands to an estimated fewer than 150, according to Perhilitan. This, despite millions upon millions of ringgit poured into conservation and anti-poaching efforts. Payne said the actual number of tigers in the wild is less than 100.

Conservationists are particularly concerned, because the Malayan tiger has similar behaviours as the Sumatran rhino - they are solitary mammals who need large roaming areas in rainforests that are now fragmented.

“The concern is the tiger population and forest density is so low that they are too scattered to breed. Half of the ones left in the wild are male and the females would mostly either be too old to reproduce or have other reproductive issues,” Payne said.

A simple analysis of the numbers alone supports these concerns.

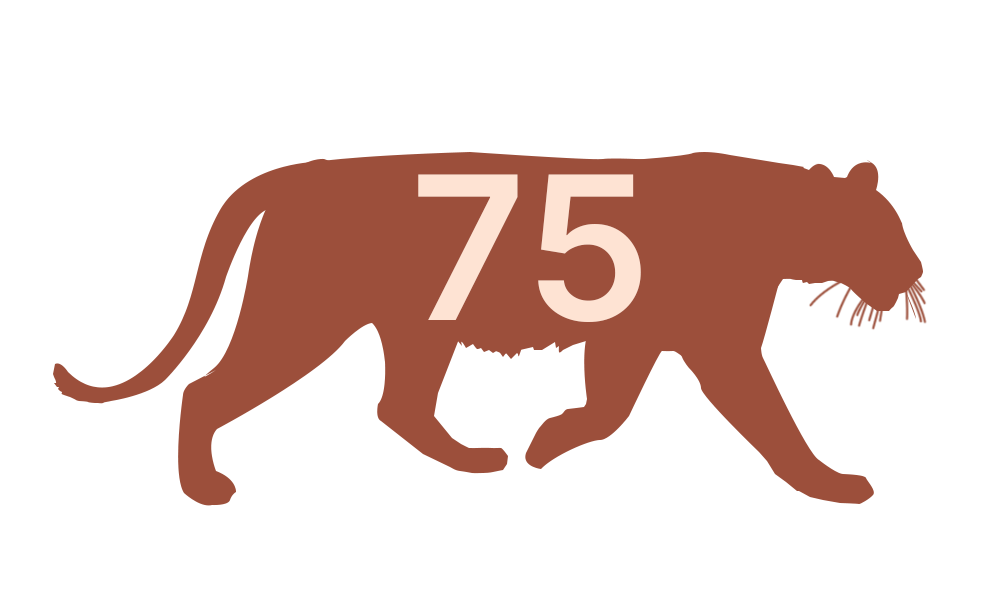

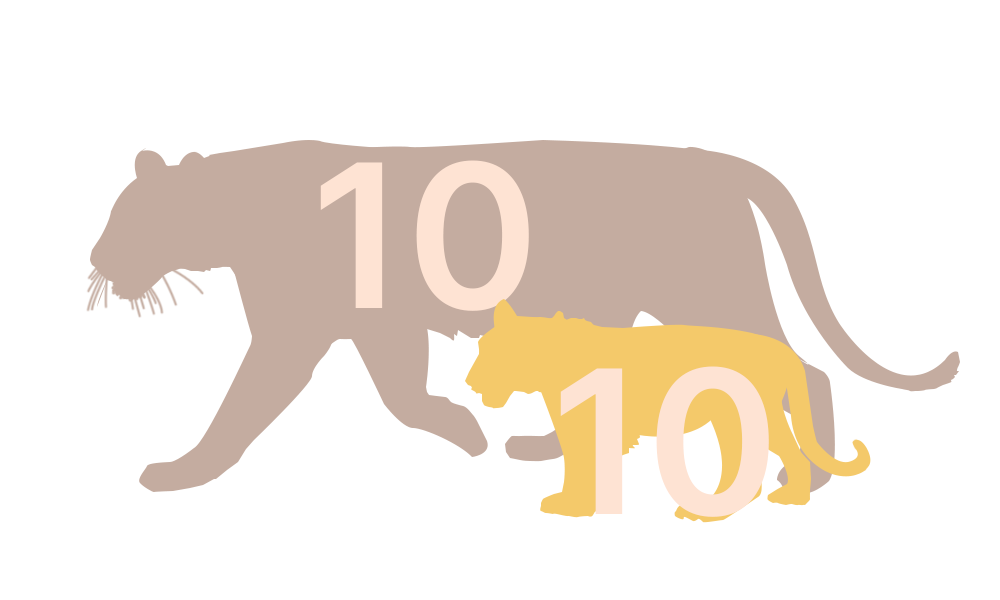

Perhilitan says there are less than 150 Malayan tigers left in the wild.

Assuming half are male, that leaves less than 75 female tigers - potential breeders.

Not all would be of breeding age. Let’s assume 10 females are too old to breed, and 10 too young.

That leaves fewer than 55 viable breeding females in the wild.

A tiger gives birth to two to four cubs every two years. If all the cubs in a litter die, a second litter may be produced within five months.

This means, if the (less than) 55 female tigers are breeding at a healthy rate in the wild, tiger cubs would be born every year.

But announcements of tiger cubs in the wild are a relative rarity, or at least not an annual affair.

Even so, when cubs are spotted in the wild, it is celebrated as proof that there is hope that tigers can still survive in their natural habitat.

“It is not too late to save tigers in the wild. We are not in a situation where there are only two or three of them left. There is hope, if we do something about it,” Payne said.

The role of captive breeding

That something, he said, is not pouring all the resources into habitat conservation and anti-poaching, even though these remain the largest threats to the Malayan tiger.

If there is a lesson to be gleaned from losing the Sumatran rhinoceros, he said, it is that tigers in zoos have a role to play and more focus should be placed on breeding captive tigers, he said.

He said more than half of the 50 Malayan tigers in captivity in Malaysia are “biologically useless” because they are too old to reproduce.

“Old tigers not only cannot reproduce, but may be in pain from age-related disease. So why not euthanise them and use the resources now used to maintain them to focus on the young tigers and encourage them to breed?”

Bringing Back Our Rare Animals (Bora) executive director

John Payne

He said if euthanising is considered unethical, they could be loaned to other zoos abroad, while Malaysian resources can be focused on breeding the ones left, with the aim of reintroducing them into the wild.

To date, conservation efforts have included introducing tiger prey into forest reserves to support the tiger population but there is no effort to introduce tigers born in captivity into the wild.

Payne said this is likely because the project is a high-risk venture. It could only bear fruit in the next 20 to 30 years, and most of the captive-born tigers sent back into the wild may die unless there is a programme to train them to hunt wild animal prey.

“It is difficult (to ensure survival of captive-born tigers in the wild) but it’s not unimaginable. To save a species we have to make hard decisions.

“This is how we can prevent extinction - better manage those in captivity so we have a living gene pool for the future,” he added.

There are already successful case studies with other species, Payne said. The European bison was saved from extinction by captive breeding in zoos. Perhilitan has successfully bred seladang and Malayan tapirs in fenced facilities.

All the best laid federal plans

In a perfect world, all parties can work together to sustain wildlife, but in reality, preserving forests and wildlife corridors is incredibly difficult and requires political will.

This is not for want of knowledge of where these endangered species roam and how much space they need.

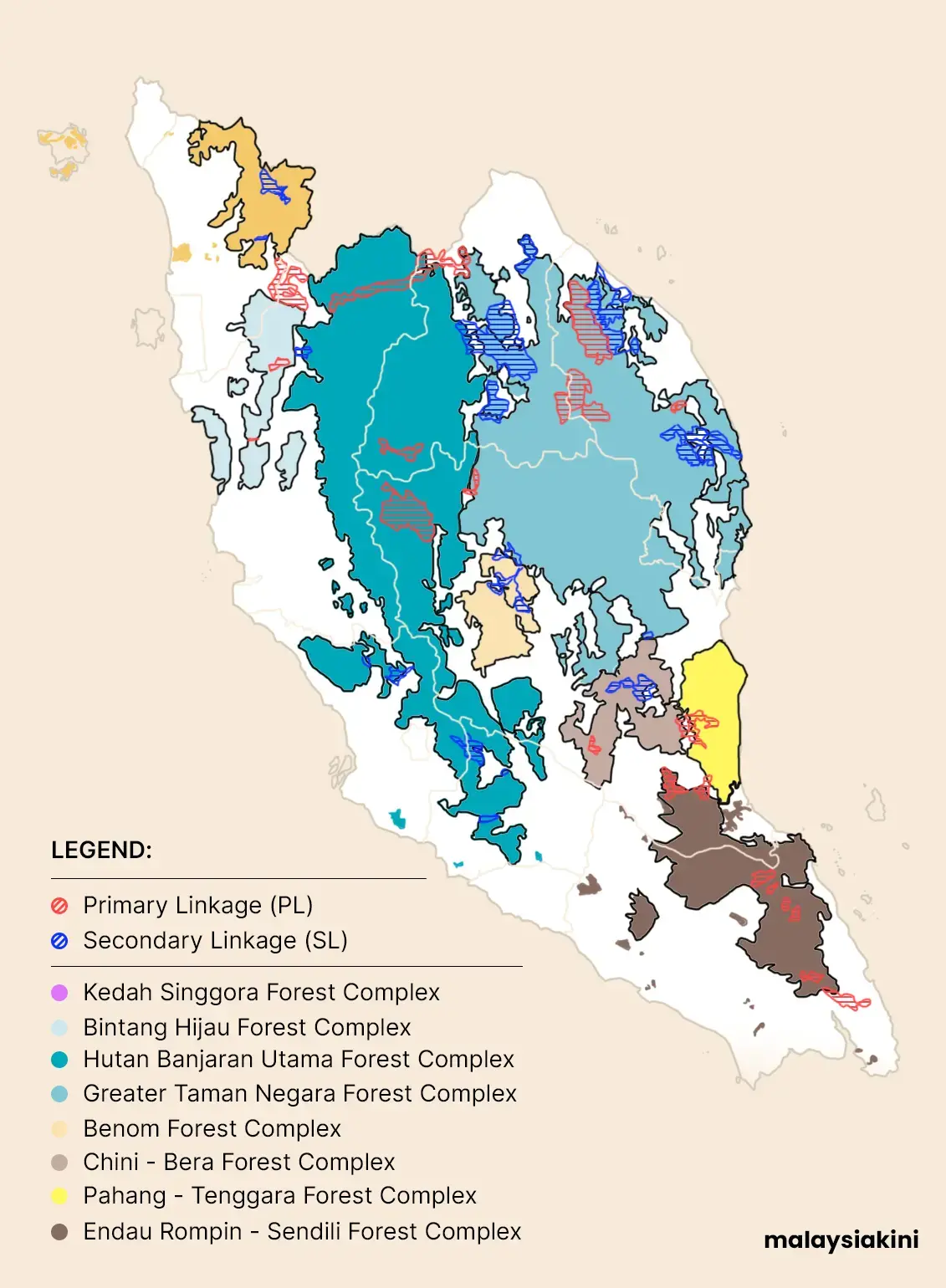

The Central Forest Spine Ecological Networks Master Plan (CFS), first launched in 2010 and updated last year, identifies ecological corridors which act as vital linkages for wildlife to move from one forest complex to another.

By right, the eight large forest complexes which fall within these corridors should not be developed or converted into other uses. This protects 4.79 million hectares of forest.

But there is a snag in the plan. The CFS is a federal plan, while all land is the sole purview of state governments.

For many states, conversion of land from forest to other uses is a driver for economic development and a source of state income. Conserving forests and the last of Malaysia’s endangered species may not bring the same economic benefits.

About a quarter of forests under the CFS are “hutan tanah kerajaan” (state-owned forests) and not gazetted as national parks or wildlife reserves.

As such, even forests that were part of the CFS ecological network were easily converted for other use. Forest cover in the CFS network shrunk by 2.61 percent compared to 2015, while land use for agriculture grew by 6.1 percent from 2010 to 2019.

This trend is unlikely to abate.

A lucrative state resource

Take the Kledang Saiong Forest Reserve (above). It is home to the endangered gibbon and 12 other endangered species and part of the CFS. It is also classified as an Environmentally Sensitive Area but this is what parts of it looked like when Malaysiakini visited in 2020.

At the time, it was not yet part of the CFS. Today, it has been included in the ecological linkages. And yet, other parts of the Kledang Saiong Forest Reserve are earmarked to become a “timber factory”.

A total 4,280 hectares or about 6,000 football fields, will be converted into a monocrop plantation. To do this, natural forests will be cleared entirely, and replaced with timber trees, the Environment Impact Assessment report which recently went up for public viewing stated.

The Department of Environment may still decide to block the project, but this could come at a cost for the Perak government.

To offset losses borne by the state governments, the federal government is offering up to RM150 million under the ecological fiscal transfer (EFT) to protect forest from development.

Source: Macaranga.org, Forestry Department Peninsular Malaysia

But this is a small sum compared to what states can earn from forestry revenues.

In 2019, Kelantan, where the Orang Asli community faced multiple conflicts with elephants, the state earned RM147 million from forestry revenues, including royalties from timber.

In the same year, Terengganu, where tigers were seen roaming on roadsides, made more than RM46 million from forestry revenue.

Both states have the most crucial, yet most threatened, ecological linkages within the CFS. Most “hutan tanah kerajaan” (state-owned forest) within the CFS network are in Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang.

Sharing the forest with wildlife

If preserving forests in their original state is too expensive for states, conservationists believe there are still ways to share the space.

Since the rhinos went extinct, Payne’s organisation, the Borneo Rhino Alliance (Bora) has been rebranded as “Bringing Back Our Rare Animals”. Among others, it now promotes creation of pastures for the wild cattle species in Sabah and in Peninsular Malaysia.

What they have learnt so far is that maintaining small parts of the lowlands in forests as pastures can be enough to sustain animals like elephants and seladang.

“We’re really talking about just a small part of a forest, and that small area can make all the difference,” Payne said.

They are also finding that planting certain types of trees, like wild ficus, can also help to sustain other wildlife, including apes and birds.

Conservationists have also found creative and pragmatic ways for humans, industry and wildlife to co-exist.

In Tawau, Sabah, plantation giant Sabah Softwoods has turned part of its plantation into a wildlife corridor connecting elephants and other wildlife in Ulu Kalumpang Forest Reserve to the larger Mount Louisa Forest Reserve.

As a result, crop damage cost went down from about RM500,000 in 2004 to just RM5,000 in 2018, Sabah Softwoods found.

The wildlife crossing is also now a conservation tourism product, with tourists paying conservation outfit 1StopBorneo Wildlife to see the 60-80 elephants, which roam in the plantation daily from a safe distance.

Last June, major plantation firms including Sime Darby Plantation, IOI Plantation and FGV Holdings followed suit.

Working with conservationists at Perhilitan and the University of Nottingham Malaysia’s Management and Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (Meme), they agreed to secure five safe passage corridors for elephants in Johor, where many human-elephant conflicts happen.

Working with the palm oil industry, long blamed for deforestation, may seem counterintuitive for some, but conservationists like Ahmad Zafir believe such pragmatic measures can make a difference between species survival or extinction.

“Wildlife really doesn't need pristine forests to survive. They just need a place where there is food and an area big enough for them to roam.”

A frozen zoo

As conservationists continue to explore pragmatic solutions to extinction threats, elsewhere, in a freezer in a university lab, lies another one waiting for its time.

Before Kertam, Iman and Puntong, the last of rhinos in Malaysia, died, scientists had collected stem cells from the mammals.

With those cells, scientists hope to develop an egg and sperm, to be fertilised and implanted in a surrogate. Alternatively, those cells can be joined with another Sumatran rhino’s somatic cell - a method used to clone Dolly, the sheep.

Working with Bora and Perhilitan, and with government funding, the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM)’s ‘Frozen Zoo’ now also houses cells from seven other species including the Malayan tiger.

There is much hope that such scientific advancements could bring back or preserve the last of Malaysia’s endangered species.

But this is the last resort, Ahmad Zafir said, and that our best efforts should be made to save the endangered animals still existing in the wild. “(We should) not wait until it is too late, to a point where we only have the cells in a frozen zoo to work with.”

Additional reporting by Koh Jun Lin, Eleena Khushaini & Sharon Juliat Selvanathan.