The following is a translation from French. To read the French version in full, visit Heidi.News.

The hardest part is over, I told myself, in my quest for Vladika Yakov, the bishop of the North Pole, Vladimir Putin's spiritual emissary on the northern ice. I was completely wrong because, on February 24, Russia launched its assault on Ukraine. And that unfortunately changed everything for me.

My obsession with Father Yakov has hounded me ever since that fleeting encounter in St. Petersburg. Every so often I wrote an email to Vladika, and he would sometimes answer with a blessing and a line hoping we would see each other in Naryan-Mar.

Then I asked help from Alexei (pseudonym), a colleague and friend from Moscow who has accompanied me several times in the Russian Arctic, could solve very complicated situations and understands the paranoid mechanisms of Putinist power.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Alexei made a plan with Father Yakov to come in the first week of March 2022, at the same time as the Maslenitsa, the days before Orthodox Lent, also known as the days of butter or pancakes. I eagerly awaited less the Russian blinis and more the traditional religious context in which I could meet Vladika in Naryan-Mar, in his large wooden church, on the majestic, still frozen Pechora River, where it flows into the Barents Sea. I envisioned myself flying with him in a helicopter to some village of Nenet reindeer herders or visiting the new Lukoil oil plants that he had blessed, as he had told me.

This is the end of January, and Russia has already amassed 130,000 men by the Ukrainian border.

One day in early February Alexei wrote that he met Yakov in Moscow. “He told me that he had been an officer of the Red Army at the Chinese border, in the mid-eighties, that it was a fundamental experience for him, one of absolute obedience. That means he was a KGB man and now an FSB man, for sure, as is Kirill, for that matter. I learned that this man has access to the Kremlin, direct relations with Putin. But we'll talk more about it later.”

In about mid-February, Alexei writes that an interesting opportunity has come up and it is worth changing plans: Vladika had organized a kind of expedition or procession in a convoy from Moscow, going north to Naryan-Mar, a six-day pilgrimage to consecrate “the patriotic way of life,” as he calls it. It would go to the monastery of the Trinity of St. Sergius, then Yaroslavi visiting the cathedral of the Assumption and the monastery of Yaroslav the Wise, then the monastery of Ipatlev in Kosstroma and other sacred sites moving up Sudislav, Makariev, Syktyvkar, Usinsk, Uhta.

The meeting point was six in the morning on February 28 in Red Square. I am on the list with a dozen Orthodox priests. The countdown to my departure coincides horribly with the CIA's predictions of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Though I wonder what the point will be of this little story of mine about the Rasputin of the tundra if the attack happens, my fixation is deaf to common sense. Then comes the “special operation” on February 24, followed by the immediate Western counterstrike in the form of sanctions, and Europe's skies closed to flights to and from Moscow. I can't leave on the 27th.

I try to get in touch with Alexei — who was supposed to pick me up at the airport at 3:00 am and bring me to the meeting point — but Alexei has gone off the radar; he last accessed his WhatsApp at 5:12 pm on February 26.

I find a flight through Istanbul for the 28th, but before I book it, I reach Vladika on the phone. At that point he is already on the pilgrimage to start his sort of Arctic St. James Way. I explain the situation, the reason why I wasn't in Red Square, and tell him that I haven't heard from Alexei.

“He has probably been arrested,” he says, “because he took part in a demonstration, or maybe because he was in contact with you … We are at war now with the West, aren't we?” He seems excited, his tone sardonic.

“Your Holiness, may I join you halfway, possibly in Syktyvkar?”

He agrees, though with a tone of skeptical indifference, and the call drops. And the ill-fated hunt is on. I go to another friend from Moscow, Maksim (pseudonym), a young economist who trained in London, who has just been fired from Nordgold, a mining company that had come under sanctions. This means he has time to give me a hand; before leaving Milan, I give him Yakov's contact information and the patriotic procession's itinerary.

At the Istanbul airport, I get this news from Maksim: Vladika wrote to him that he is no longer willing to take me with them.

He says that “everything changes due to circumstances, and it is obvious that the original plans are unrealistic, having become pointless after 2/24. We have other priorities that everything else must be subject to, including our earthly life,” he writes on Telegram. “Every external factor is insignificant. Everything that does not fully concern our mission is beyond it.”

Maksim is confused. He is used to numbers, not these mysterious proclamations: “Are you really sure you want to meet such a strange character?” he writes.

On March 1st, we have lunch together near Belorussky Station in Moscow. How's it going, Maksim?

“I just spent two weeks in Cuba,” he tells me. “I was looking at their system, the two currencies, the black market, the broken-down Zhiguli cars, and everything. It's like it used to be here, I thought, almost amused. Now that'll be my future, except the Zhiguli car.”

He shows me the chats on his cell phone from friends who suggest he join them to flee to Georgia, and from his mother, who suggests he stockpile food:

“Her generation went through hunger in the 1990s. She still remembers the joy of a birthday present of a package of Nescafé. I bought some things yesterday. One thing surprised me; olive oil has vanished from the shelves. See how spoiled we've become over these years? Now you know what to bring me next time, a bottle of olive oil. I'll sell it to pay my mortgage.”

Then he tells me he's waiting for a phone call and something incredible could happen.

One of his friends works for a woman named Ekaterina Kuzmina, who leads an NGO called Mammoth Effect, which produces documentaries on climate change in the Arctic. It coordinates several million-dollar scientific projects in eastern Siberia and in Yakutia about cloning the woolly mammoth, which went extinct with the last ice age.

“Russian, Japanese, Korean and American funds and scientists are involved. But now, with the war, everything has fallen apart. I think we'll have to wait for the next ice age.”

“Maksim, what do mammoths have to do with anything? I want the bishop.”

“It seems that Ekaterina is very close to him. She's given him a lot of money. Yakov is even her spiritual father. She'll call him to convince him to see you, directly in Naryan-Mar at this point, I imagine.”

Maksim's friend does call and tells us that there the chances are good, that Ekaterina wants to see me in two days for breakfast, at Coffee Buro, across the old Politburo building and near the headquarters of VTB Bank, of which Ekaterina is a senior manager. And there's another thing. Maksim has arranged a meeting with a person, a former engineer in the Lukoil plant in the upper Pechora basin. He can tell me some things about Vladika. He has met him and is in touch with dissident circles of the Patriarchate.

We meet at the Patriarchal Bridge, next to the Church of Christ the Saviour, with a view of the Kremlin. The sirens of police vans wail, going to round up the pacifists in Puskin Square.

“The religious expedition that you were going to take part in started right here,” says Maksim, who is a devout Christian and opposes Kirill's warmongering.

“Because it is a highly symbolic place for these fascist crusaders. Yakov organized it to celebrate the invasion of Ukraine, a full pilgrimage to ask God for the conquest of Ukraine and the annihilation of the schismatic church of Kiev. Vladika is the point of contact between Kirill and the military. See down there?” he points from the bridge to the lower part of the cathedral.

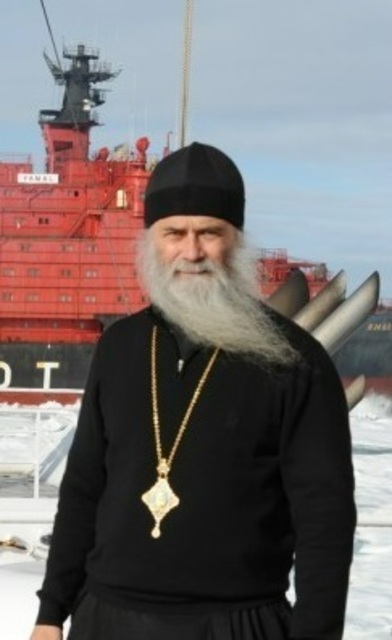

A cold wind ruffles the blond hair on his forehead. “On the evening of February 27th, I know for a fact that there was a meeting where officials of the Ministry of Defense were there with Bishop Yakov and others, including Mitrofan, the Metropolitan of Murmansk, who is a complete fanatic. The engineer speaks excitedly, his eyes narrowed. He fidgets with the wooden cross that hangs on a chain around his neck. Yakov has blessed fourteen new military bases in the Arctic. In 2017 he flew with Putin, Prime Minister Dmitrij Medvedev and Defense Minister Sergei Shojgu to the island of Alexandra, in the Francis Joseph Land, to consecrate the Arctic Trefoil base, which is the most advanced base in the polar ocean, like a spaceship equipped for a war in the ice, with a heated landing strip for fighter and bomber jets.

In 2012, Yakov was the first prelate in history to reach the North Pole as a representative of Kirill. He had a titanium capsule sunk there, holding a document with which the patriarch claimed Russia's historical and religious dominance over the Arctic.”

Ekaterina arrives right on time to our appointment. Or, more precisely, she appears. She materializes at Coffee Buro like an archangel, in her thirties, dressed in a sky blue pantsuit, patent leather blue shoes, 6-inch heels, a deep neckline. Her beautiful face is framed by a brown page boy:

“Hello, I'm Katya.”

I'm dazzled. Maksim was telling me about Fyodor, his aunt's Ukrainian husband, who is barricaded in the Zaporizzja nuclear power plant under Russian attack in the south of Ukraine. Now we are engulfed by the look in Katya's green eyes.

She introduces herself, stretching out the back of her pale hand, showing off the big diamond on it as if it were a calling card. My hunt for the bishop seems to be over. I can almost taste my prey.

Katya announces that Yakov has agreed to meet me in Naryan-Mar. His “patriarchal journey” is going faster than expected. He will be home in a day, and he has made all kinds of arrangements for me, including using a helicopter to reach some outposts of faith in the tundra, and maybe even Belushya Guba in Novaya Zemlya, where he has a new church to consecrate. I'll have a lot to talk about with him, about the behind-the-scenes of the war, face to face with one of the great minds fueling the doctrine of imperial rebirth.

Katya asks me to send her a short resume and a general list of the topics I plan to talk about with Vladika. She also calls her colleague at the bank to check flights for Naryan-Mar. There's one in the late afternoon through Arkhangelsk. I'll have to spend the night there, in the “gateway to the Arctic,” on the shores of the White Sea and then continue in the morning.

“How I envy you. I'd like to come too,” says Katya. “That's my favorite part of the Arctic. We've done permafrost research projects in that area. But I've already planned a few days of vacation. We have a dacha in Abakan in Siberia, near Krasnoyarsk. I can't wait to go skiing again.”

The war seems to have not touched her comfortable life in the least. Or is she feigning calm to impress the Westerner? When I get back from Naryan-Mar, we'll meet again, she says. She promises that we will go to see her friend Artur Nikolayevich Chilingarov, the mythical polar explorer, decorated Hero of the Soviet Union, member of the Academy of Sciences and deputy to the Duma in Putin's party.

“He can tell you about when he was at the North Pole with Vladika and the miracle happened,” Katya says, looking skyward, as if to get a confirmation from above.

“The sky was dark and there were banks of fog, but when Vladika lowered the capsule into the ice with the message of His Holiness Patriarch Kirill, the sky suddenly cleared, and a rainbow appeared.”

Translated by Miriam Hurley.

- View this story on Reportagen

- View this story on L'Internazionale