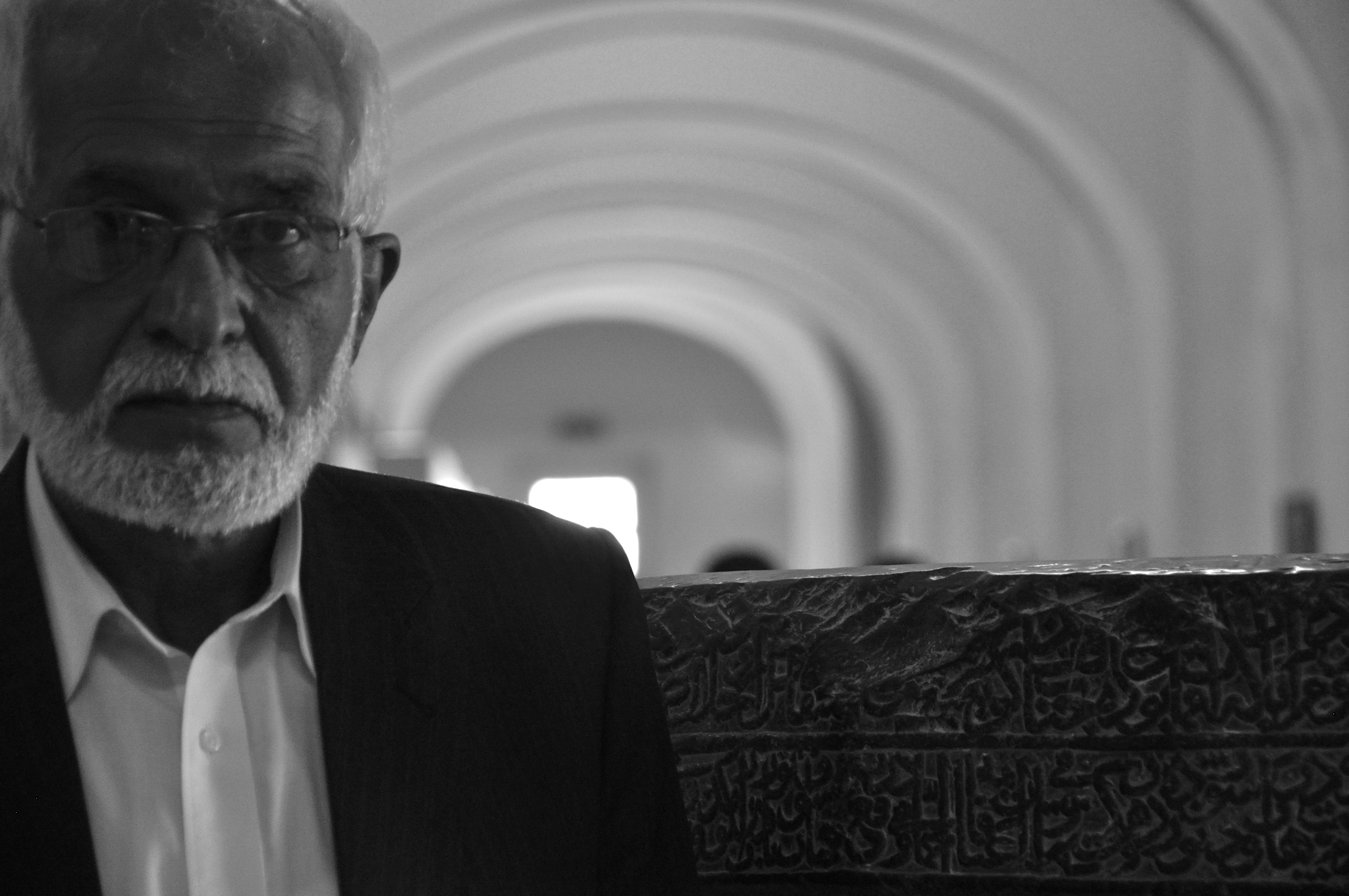

Name: Omara Khan Massoudi

Age: 63

Ethnicity: Pashtun

Province: Logar

Omara Khan Massoudi is the Director of Afghanistan's National Museum, guarding its treasures in various positions for more than four decades, and is the reason it has been brought back to life. He is an elegant man and old-fashioned in his habits, but his gentle air belies a ferocity with which he has fought to preserve the country's archeological history, keeping the museum doors open even when there was no roof over head, no visitors in the halls, and hardly any artifacts in the display cases.

The museum has a grandeur about it, and its well-tended grounds evoke the garden city Kabul once was. But this is a recent development. The museum sits next to Tapa-e Scud -- Scud Hill -- so named for the missiles that were placed there and then left behind by the Soviets, and which helped turn the area into a strategic one for any army trying to control the city. The mujahedeen also paid special attention to this place, going up and down the main road firing all kinds of artillery, leaving roofs collapsed and walls freckled with rounds of various caliber. In this part of the city, buildings survived decades of war but barely, and the collapsed domes of the once-opulent Darulaman palace -- visible from every front-facing window in the museum -- speak powerfully to the condition of a country whose rich cultural heritage is still visible, but in skeleton form.

The following are the words of Omara Khan Massoudi, as told to Jeffrey E. Stern

In 1973, when I graduated from Kabul University I find a job as a teacher. For four years I was teaching history and geography. When the period of revolution came in Afghanistan in 1978, it was a little bit difficult how to teach the young people. At my school, they were really intelligent students, they studied too much, but after the period of revolution, unfortunately, slowly slowly their attention to the learning was day-by-day getting weaker. Especially these young people, these young students, when they had relations with political parties, sometimes they didn't come to their classes.

That was difficult for me so I took that decision to change my job. At that time I was 24 years old, 25 years old. I come to the Ministry of Information and Culture, for four months I did my job over there, then there was a position here at the national museum. The museum staff gave me some training, day-by-day my interest was too much, I stayed here, and worked. And continued up to now.

Maybe you know that in 1987 or 1988, when the Soviets left Afghanistan, we Afghan people, we predicted that the Communist party will have to transfer the power to the mujahedeen. Everybody predicted that. Sometimes in the non-developed country, when political changes is coming, sometime there is political gap also. And I think it was the museum people's responsibility to safeguard all the artifacts which were here. In my opinion, the cultural property, the -- how to say, can I use "capital of nation"? -- these artifacts not only belongs to us. We keep these things, but really, they belong to the people all over the world.

So we thought about if the situation is getting a worse, what should we do? How to protect artifacts here?

As you know this museum is located around 10 km far away from the center of the city. So we predicted that if something happens one place -- if there was fighting -- maybe the second or third places will be safe. We shared this idea with our minister at that time, he kindly accepted, he said: "This is good idea," and he shared it with the president. He also accepted. He ordered that "any place the museum people say, I will give order to them, so they can shift the artifacts where they want."

So for safeguarding all these artifacts, we shifted to two places and decided to not give any information to anyone that we shifted these important pieces.

***

In the end of 1992, the situation in Kabul got worse; day-by-day the civil war started between different groups of mujahedeen. First, the artifacts that remained in this present building were looted too much. I remember, when this museum was looted, nearly 70 percent of our artifacts, they looted from this museum.

Some journalist asked about the Bactrian treasure because not a single piece of gold had come out on the black market: "Many artifacts come to the black market, but there is not a single piece of Bactrian treasure. Where is it?" We had shifted all of it, all the golden coins, golden pieces; we shifted from this museum to a vault. But we didn't give any information. "We don't know where is it," we said; "Is it here, or there?" We keep silent our mouths.

Some newspaper wrote some article about these pieces. I remember one article in Le Monde newspaper in Paris, they write that the Soviet Union forces shipped all the Bactrian treasure to Moscow. It was not true! It was wrong! But we didn't write the answer for that.

***

During the Taliban, at first they pay attention. Not only to the museum, but the ancient site, and historical monuments also. They protected them, they paid attention, especially they pay attention how to stop the illegal excavation. I remember, I was a member of a delegation that went to an ancient site which was, by illegal excavation, it was being looted. We got the artifacts which were over there, we got them shifted from there to here at the museum.

But unfortunately, in the beginning of 2001, the Taliban changed their mind. They destroyed all these pieces.

When international forces came, the museum was in very bad condition. It had been looted, it had took fire, believe me there was no windows, there was no roof, there was not even doors in front of the storage.

Day-by-day, we went on with the rebuilding; I contact the U.S. embassy, the director of planning department, and we had a meeting with the cultural attaché of U.S. embassy here in Kabul. He promised to pay around $100,000 for reconstruction of this building. I was too much happy. We started from zero point, but day-by-day, day-by-day, the reconstruction went on.

In September 2004 we had an opening ceremony, our president Karzai came and attended with some cabinet members. Then slowly we are moving, up to now, you can see this museum is open for the public always, there are tourists coming to this museum.

But, we had a lot of serious problems. The remaining pieces, all of them, needed urgent treatment, they needed cleaning. For years, by the leaking of water, they were damaged; some of them were in very bad condition. Believe me, there was nothing. There was no table, there was no desk, there was no chair for my staff to sit on. Our restoration department was too weak. This current building doesn't have some necessary things which is much important for museums all over the world. Like security signals, we don't have. Also we don't have heating system, we don't have humidity control system. We don't have fire barricade system here in this building, the lighting system is not good. The building is also too small, it's not big enough for a national museum.

We have some serious problems, but I believe we can solve them. Not very soon, but day-by-day we'll be able to solve these problems. We want to have a new building. We'll have technical X-ray machine, now it's too difficult to physically check the ladies, the women, the kids. This is not a polite way, but what to do? The situation in Afghanistan is like this.

I'm optimistic that foreign countries will take part to support this. I hope we will have these things in the future. But all these serious problems I mentioned, it will be solved in the new building.

I think usually I am a gentleman that is optimistic. We have to always think positive things. I hope this will be not a dangerous year for us, that we will have a good election, that we will have a good government, and also that foreigner countries will support Afghanistan. If this is the case, I'm optimistic. Our people must tire from this long war. Three decades war, in my opinion, it is too long. And also, it is too boring for our people. Even all the people, the ISAF and NATO people, they know that very well. I hope that they will support Afghanistan in future also. The peace will come. I'm not afraid too much that the civil war will again start. This is our responsibility, the Afghan nation is responsible. We have to be careful, we have to not go back to 1990s. What happened to this country, what happened in Kabul, this old experience, we have to not repeat it.

We have to learn some things from the history.