In 2015, Zika was dominating international headlines. While the virus had been discovered in 1947, its ties to microcephaly and severe birth defects were new and raised concerns around the globe. El Salvador reported its first case in March 2015, and the Center for Disease Control still suggests that pregnant women, partners of pregnant women, or those considering pregnancy avoid the country due to the virus.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the only crisis facing the country. Gang violence fueled by a lack of opportunity and an adjacent drug trade had made El Salvador the most dangerous country in the world outside of a war zone. And while violence affects everyone, women and girls in the country were being impacted differently.

El Salvador leads Latin America in unintended adolescent pregnancy and femicide. One in eight women reports experiencing physical or sexual violence, and until August 2017, child marriage under age 18, was legal under certain circumstances. Reproductive health education is extremely limited, contraception is hard to access, and abortion is illegal under any circumstance. In July 2017, 19-year-old Evelyn Beatriz Hernandez Cruz, pregnant as a result of rape, miscarried and was sentenced to 30 years in jail.

Machismo and religion are so ingrained in the culture that while these injustices are a part of everyday life, talking about them remains somewhat taboo. “There is no hope for women in El Salvador,” sighed one international aid worker who worked with PASMO/PSI, a women’s health organization, and asked to not be identified.

And then came Zika.

The initial response to the virus was panic. With so little understanding of why and how Zika was causing microcephaly, the idea that the virus could hit a country already devastated by poverty and violence was a frightening prospect. With the memory of the Ebola outbreak fresh in their minds, USAID poured money into the international aid response.

The Deputy Health Minister Eduardo Espinoza said that women should ‘hold off on becoming pregnant’ until the virus could be contained. ‘…For one year, maybe two.’ Which is almost understandable. At first, nobody knew what to do, they just knew they had to do something.

Zika itself only presents as a mild fever or rash. It was the devastating impacts of microcephaly in a fetus that made the virus such a threat to women. Additionally, research showed that Zika could be spread by both sexual transmission and mosquitos—a phenomenon never been seen before.

To fight Zika, it wouldn’t be enough to hand out mosquito nets and bug spray. Successfully combating the virus would require the incorporation of family planning and reproductive health education. This demanded an education campaign to teach both men and women about the need for safe sex practices. “It was the first time that a public health approach could be integrated into disaster response,” said Dr. Christina.Yarrington, a OBGYN at Boston Medical Hospital.

If this could be accomplished in El Salvador, could it lead to long-term changes in access to reproductive healthcare? And could these changes help to push back against the cultural factors that were already negatively impacting women and girls?

Two years later, we take a look back and ask: Was Zika and the disaster response a catalyst for structural and cultural change for women’s health in El Salvador?

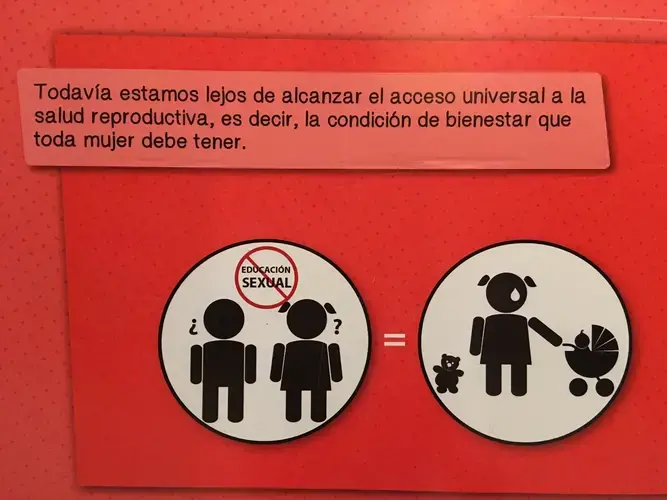

No Sex Ed

Sex is everywhere, but talking about it is taboo. When asked, the response in the country is accompanied with raised eyebrows. “Educación sexual?” scoffed Aldo Miranda, a Salvadoran research director as he sucked air through his teeth and considered the question. “No, there is very little sex education in El Salvador.”

In public schools, there is little to no time or energy dedicated to sex education. Public school teachers are tasked with managing large classes, navigating the very real threat of gang violence, and teaching multiple subjects.

When asked what kind of sex education children receive, Miguel Angel Gamez, the principal of Centro Escolar Luz de Sotomayor in the hot and hectic coastal town of La Libertad scoffed and said that that the science teacher will sometimes try to fit in a week of sex ed into their yearly curriculum, but it is usually met with so much pushback from parents that they often abandon the effort. “Fathers don’t understand why we would want to teach their daughters about sex,” he said.

And yet, in the past year, at least three girls under 16 dropped out of school when they became pregnant. “They were embarrassed,” said the principal.

The Ministry of Education has developed a comprehensive curriculum for reproductive health education, which is available online. But when they tried to turn it into a textbook, it was met with so much opposition from religious lobbyists that they abandoned the initiative.

“Abstinence only” sex education typically has no impact on delaying intercourse in adolescents and has actually been shown to increase rates of sexually transmitted infections. In El Salvador, the lack of comprehensive sex education has led to high rates of adolescent pregnancy, sexual assault, and higher rates of maternal mortality.

Clinicians see the repercussions of the lack of sex education every day. Dr. Altagracia Solorzano, who recently retired after a 30-year career as an OBGYN in an inner-city hospital, was incredulous about her experiences. She had worked before the civil war, during the civil war (when NGOs were intent on delivering aid) and after the civil war, (when many NGOs left to the country to respond to the next conflict). “Even after all these years and all these changes, one third of babies continue to be born to girls under 18,” she said as she shook her head. “There has been no change.”

While poor women are particularly vulnerable, all women are subject to the same cultural stigmas. “Family planning is basically non-existent in El Salvador,” said Dr. Solorzano. “The only women I know who plan their pregnancies are medical students planning around their residencies.”

Why is there a lack of sex education, and who is responsible for fixing this problem? “The culture,” said some. “Religion,” sighed others. “Machismo!”

Perhaps it is the combination of all three. “Everything reinforces this idea.” said Maribel Dignaca, a teacher in San Salvador. “Everything is against the woman, and it maintains the status quo. Parents teach the children, and it inculcates and inculcates. Eventually as the children grows, it becomes fossilized.”

And then came Zika.

Zika was an emergency. It was a frightening, unknown disease that affected society’s most cherished asset—infants. But just because there is a crisis, people do not stop having sex, and women do not stop getting pregnant. Men could catch the virus from a mosquito, then spread it to their female partner at any point before or during a pregnancy. The implications were frightening.

Frightening enough to open a window of opportunity and create lasting change?

Crisis Response to Zika

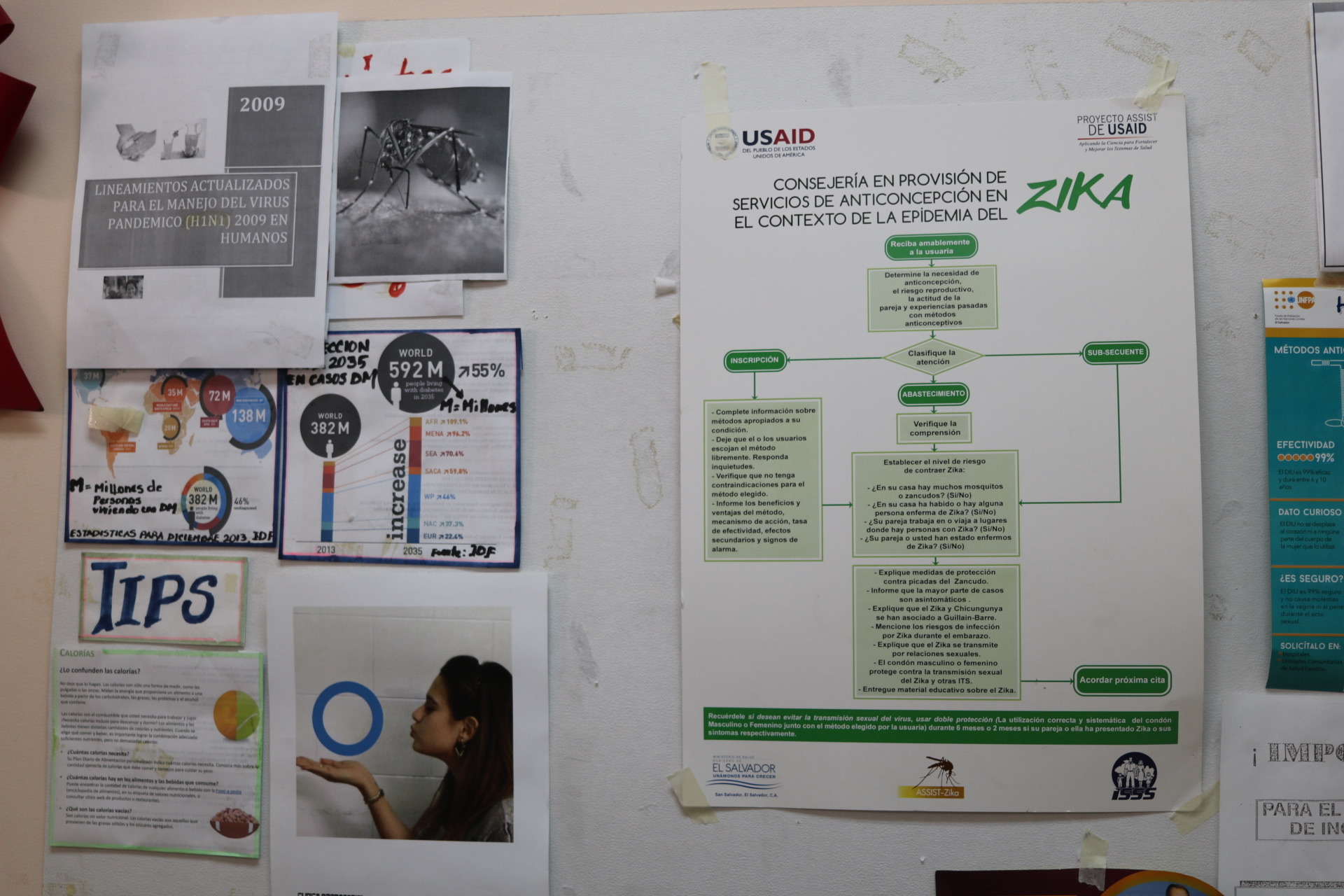

In March 2016, the international aid community sprang into action. USAID developed promotional materials and granted three year contracts to organizations like Medical Care Development International (MCDI), the International Red Cross, PLAN International, PASMO/ PSI and others.

What is most striking about the disaster response are the logistical challenges. Who could work where, and what would they work on? “When the Zika crisis began, there wasn’t sufficient evidence to conclude that Zika could be sexually transmitted,” said Cristina Perez de Natividad, the National Advisor for Resilience and Humanitarian Action with PLAN international, “so initial proposals and plans didn’t include reproductive health education.”

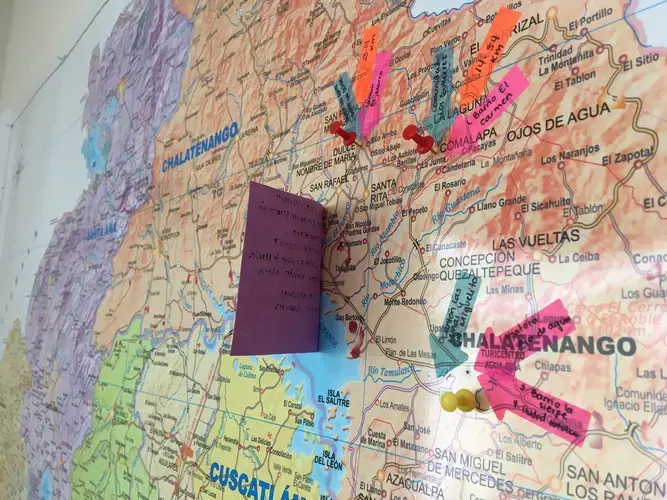

Each organization was forced to navigate the political landscape, funding requirements, and on-the-ground challenges. Some neighborhoods are inaccessible due to violence, and so aid organizations simply don’t go there.

After receiving approval from the Department of Health, each aid organization was tasked with tackling a different side of the virus. One focused on direct service care, one on mosquito control, others on behavioral change and education campaigns.

“The hardest part was first educating people that there was a danger, and then teaching them how to prevent it,” said Stephanie Alfaro, a lead coordinator for MCDI. “With public health, good prevention means you don’t see the problem, which can lead to reverting back to risky behavior.”

NGOs were able to create materials to educate people about limiting mosquito breeding sites and ads designed to encourage married pregnant couples to use condoms, but these efforts took time. Bus banners and radio ads about Zika and the need for prevention through safe sex only started to appear during the summer of 2017.

No Zika

In El Salvador today, the fear of Zika is all but gone. “Salvadorians have a short attention span,” said Perez. "There is always a new crisis, and so we forget the last one quickly.” Most people now seem to brush off the idea with a similar sense of indifference. ‘Zika? No, Zika never came to El Salvador.’

Which isn’t true. According to the CDC there have been over 7,000 cases of Zika since 2016, including 159 cases in pregnant women. But the nature of the virus could have also led to drastic underreporting. Eight out of 10 people who contract Zika don’t know they have it. The symptoms are relatively mild and include red eyes, a skin rash, joint pain, or a fever. For people living in a tropical zone, these symptoms might easily go unnoticed. “It’s 89 degrees today, como un horno” (“like an oven”), one health worker said. “We might have fevers right now and not even know it.”

Health Care System

In 2009, the newly empowered Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional, (FMLN) government instituted free public healthcare. But the care you receive depends on where you live, what supplies are on hand, and how long you’re willing to wait.

And while the public health system is free, getting there may require a day of travel or mean long waits once they arrive. In many parts of the country the system is often overloaded. “About a year ago, I was so sick,” said a cab driver as he sat in the snarl of San Salvador's unforgiving congestion. “I felt weak, with a fever and body aches. But I went to the hospital, and they said that there weren’t enough beds for me to stay there, and so I might as well go home. Maybe it was Zika!”

Maybe. But maybe it was a myriad of other similar tropical infections like Chikungunya or Dengue.

Today, if you arrive at a public hospital with Zika-related symptoms, you will get educational materials about prevention. If you are pregnant, you will leave with a Mama Segura (Safe Mother) bag, filled with 10 condoms, bug spray, and a fact sheet. Getting an official Zika diagnosis requires a blood sample being sent to the CDC in Atlanta, a prohibitively expensive procedure. Therefore, most cases are marked as suspicions and not actually diagnoses.

The private health system is not required to report back to the government—meaning that if Zika was diagnosed in a patient, those numbers would not show up in the official reporting.

A Missed Opportunity

“Sex education needs to start early,” said Don Ellio, a local health educator in EL Zonte. “And it has to give more than just biology or how to prevent a pregnancy with Zika. It has to include respect and how to love each other.”

Sitting in the school teacher’s office, surrounded by tall stacks of papers and supplies, the principal Mr. Gamez chatted with another teacher about the sex education program of their dreams. “If there could be more assistance from the Ministry of Education or Health, like specialized teachers or curriculum, that would help.”

And yet, a box covered with dust and filled with untouched USAID curriculums for reproductive health lesson plans, sits by the door. There just wasn’t enough time for the teachers to use it.

The Ministry of Health has since rescinded its statement about avoiding pregnancy. The Zika virus had brought attention and resources to El Salvador, but it was not enough to force structural changes in the education or medical systems in the country. Lasting change would require more investment in teachers, health educators or programs designed to empower young girls and educate young boys.