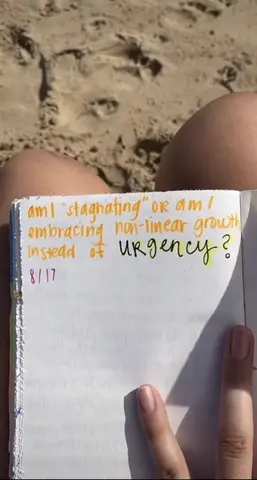

The full moon shines big and bright in the hazy, humid August sky. On the rooftop of my hostel home, my eyes are locked on the Atlantic horizon of San Juan, Puerto Rico, as the lunar cycle relishes in its halfway point. Tomorrow the moon takes a step towards rebirth in a pattern of waning and waxing that it has known forever. I look down at the prompt in my journal:

Am I stagnating, or am I embracing non-linear growth instead of urgency?

Scrolling through WhatsApp again, I’m noting nonresponse, scheduling, and rescheduling, searching for connections. I type in a number, but I don’t call. A familiar mental loop of possibility and insecurity picks apart my brain as the mosquitos swarm my tanned legs and arms. The cycle continues: my thoughts raced to consider leads and how to follow them, becoming derailed by lingering irrationalities of incompetence and feeling out-of-place. My mom lights up my phone to ask when I’ll be home. I count 53 bug bites on my body. Much like destructive thought patterns, they only get worse if you scratch them.

I had plans to visit Puerto Rico over a year before this to report on the connection that the Indigenous Boriken Taíno people hold with their island. I intended to explore how traditional Taíno knowledge can help us mitigate climate change-related disasters and their effects: rising sea levels, destruction of ancestral lands, and forced migration patterns. I knew some version of me was capable of finishing this project. I already possessed the technical, creative, and linguistic skills required to film an impactful documentary. The greatest challenge I faced in my pursuit of this project was my personal struggle to reclaim my power in the wake of post-graduation and pandemic-fueled anxiety, uncertainty, and defeat.

Upon my graduation from American University, I resembled more of a trembling child than a motivated budding filmmaker when I glanced in the mirror of my childhood bedroom. I reasoned that some version of me was good enough to accomplish my goals. I lost that version for a while in the haze of quarantine—with a series of life changes and shattering headlines shaking my day-to-day. I spent the better half of 2020 and 2021 mourning that capable person and the promising world that she was about to break into. In August of 2021, I broke the cycle of lying-in-wait. Pep-talked and patched-up, I threw a backpack over my double-vaccinated arm and boarded a flight to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

I had the exciting and terrifying feeling of starting a cycle of rebirth as I stared out over the endless blue of the Atlantic Ocean. I moved around and rebuilt my life more times in 2020 and 2021 than I ever had before. I was convinced that this time would be the best yet. “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” it was everything in between, and it was far more.

I extended my trip four times, missing flights I had hoped to catch over the three months I spent there to chase this story all over the Puerto Rican archipelago. I took that time to experience the environment in which I was reporting.

I had visited the island twice before: once as a child, spending days I half-remember now on a beautiful resort that Hurricane Maria later took with it into the Atlantic; the second a spontaneous trip one summer in college, where I met my first love. The beach used to connect from where the kite surfers catch the daily winds all the way over to the east where a local park sits oceanside. My girlfriend Klaudia and I walked along the sand to find the spot where we had first connected now underwater. Where we had once descended onto the beach together now sit eroded cinder blocks, jagged gray stones, and stairs that lead to nowhere.

Everyone asked me when I mentioned my trip to Puerto Rico, “How have they recovered?” There’s this dark cloud that looms over the foreign view of the island. Its recent fate of alarming natural disasters seems to shadow the outsider’s perspective of the U.S. territory: intense earthquakes, rising sea levels, and the infamously destructive Hurricane Maria in 2017.

One narrative about Puerto Rico you can find in the resorts lining the northern shore like scattered seashells on the capital city’s beaches: “Recovery has gone swimmingly, and we welcome tourists to paradise!” Oblivious to the colonial status of Puerto Rico are the many tourists who engage with the island’s happiness and not its hardship, using their American passports to traverse the U.S. territory. I certainly recognize my privilege to have done so on past trips to the island. Spanish colonization is a painful chapter of the island’s history, but the ongoing legacy of U.S. imperialism continues to influence its present and future.

The more realistic narrative requires outsiders to listen to residents who have lived it firsthand. Millions have left the island while others swear they never will, despite surviving climate change-induced disasters, facing a lack of economic opportunity, and living with inadequate infrastructure.

Enveloped in the island’s lushness, you can’t help but feel the powerful connection natives of the island describe. I spoke with Puerto Ricans about the beauty and sanctity of their land. Everyone I interviewed, especially those with strong Taíno Indigenous roots, feels a spiritual or moral responsibility to take care of the island. One elder and activist told me that the Taínos have always been known as great observers of the world around them. This aids them in understanding how they must give back to the island for all it gives to them.

From the flora and fauna of the mountainous rainforests to the marine life on the reefs and beaches: every part of the island is poetry, is connected, is alive. Every part of the island is in sync with nature’s cycles. Every part of the island is important and worth saving. The hallowing truth I learned from those most connected to the land is that every part of the island is in danger as long as the climate crisis remains a threat.

The sweltering days stuck together like pages in a book until the wet heat broke into the torrential downpour that marked each afternoon. You’d start to see the clouds roll in and ruin everyone’s beach day, and we would go from sunbathing to running for cover in minutes.

Our power would go out from time to time at the hostel, and I thought that traffic would stop when the power lines exploded across the street in an extravagant fireworks display. The cars swerved but kept moving. I ran four flights of stairs down to the street. We turned on our generator. Our neighbors spent those afternoons in the dark.

San Juan’s nights are colorful, lit up by the strobe lights of the lively clubs and bars which dotted the street where I lived. The distant pounding of reggaeton never stops. Giant speakers mounted on trucks sped down the street night after night. I’d listen as the pitch of the familiar melodies changed on their way towards and past me. I pondered the Doppler Effect: same song, different perspective. Little moments like that can illustrate hindsight perfectly.

Perspective hit me hard coming out of lockdown in Washington, D.C. I had my small circle. Everyone around me got vaccinated and wore masks. Puerto Rican residents were leading the charge nationwide in terms of vaccination rates, but I saw visitors neglecting to take precautions in the throes of the Delta variant wave. Coming face to face with fake vaccination cards, botched tests, and reckless attitudes toward public health presented me with culture shock. During my trip, city-wide curfews were enacted and vaccine mandates sprung up everywhere. The situation uncovered new layers by which to examine the reality I was living and presented unique challenges.

Fighting imposter syndrome was an uphill battle from the moment I started my first interview for this documentary. Though I perfected my questions, I found out the hard way that my camera batteries hated the heat as much as I did. Another time, I felt a rush of defeat knowing I had traveled hours only to be canceled on. I almost got kicked out of a venue I thought I’d had permission to film at. I picked myself up each time and moved forward. I redirected my project, found new leads, followed different stories. I made lasting connections, created five terabytes of footage, and lived out memories that I will tell for the rest of my life. All the while, I felt these waves of inadequacy reappear as they had before, cycling in my mind as the humid air fogged up my camera lens. I learned that my greatest asset moving forward would be investing in my mental health, and being so hard on myself would be my downfall.

I remember one new moon night in the jungle. Bright blue mycelium lit up my hands and face and I had never seen anything like it before. Mycelium is a gigantic fungus that connects living things through its extensive branch systems. It aids the cycle of life, death, and rebirth as it breaks down old life and transforms it into life force for the new. It glows with life in the forest when the conditions are right. The next time the moon was new, it was my 22nd birthday. My friends and I went swimming in the bioluminescent bay off the southern coast of the main island. We dove into dark Caribbean waters and saw millions of bacteria light our path. The pitch darkness of the night sky created ideal conditions for this natural wonder. You can’t see it every night—there, too, is a time for this wonder to shine its brightest.

I spent almost every day in the ocean, giving in to the movement of the waves. I looked to the ocean as a reminder of the importance of cycles: studying the swell, the push, and the pull of the water. I noticed the rise and fall of the tides controlled by the moon’s force. Witnessing nature’s ongoing cycles remind me that there’s a time for everything: for reflection, for rebirth, and for action.