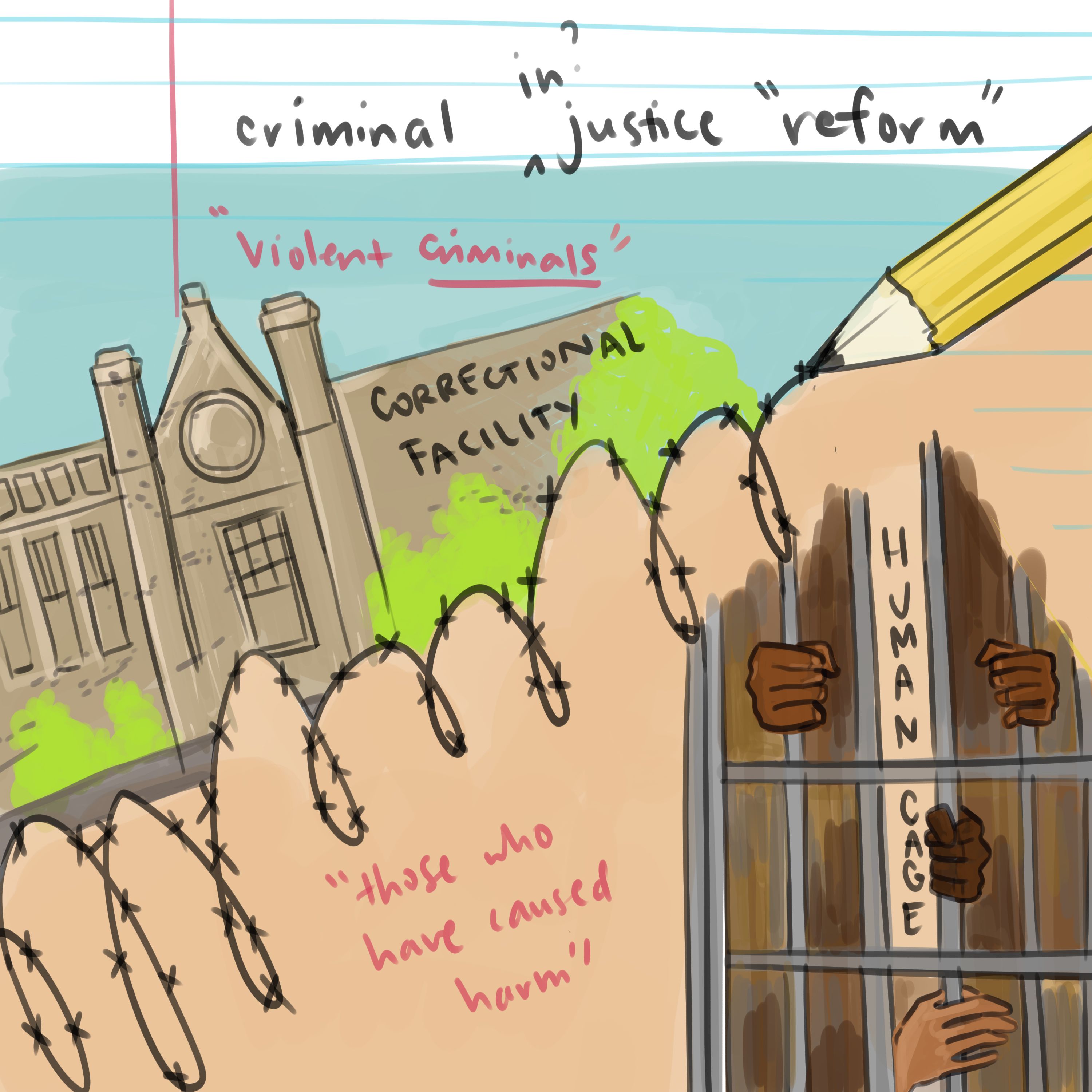

“Inmate” or “incarcerated person?” “Prison” or “human cage?” “Reform” or “reimagine?” These are just a few of the many decisions we make in describing those affected by the carceral state. As a journalist, I have learned that when it comes to discussing the criminal justice system, the language we use matters. Is it the criminal justice system or criminal injustice system? Does calling it the criminal justice system legitimize the notion that it actually delivers justice? Or does it just describe our expectations of the system, whether it delivers or not? Perhaps it’s best to extricate the notion of justice altogether and call it the criminal legal system. Or maybe that’s overly pessimistic, assuming that just because the system doesn’t deliver justice today that it never will.

These are the internal debates that have come to define my reporting as I’ve interviewed various wrongful conviction attorneys and prison abolitionist organizers. And it’s not just about semantics. Rather, the language we use is intrinsically tied to notions of power—who has it, who doesn’t, and who should. Is someone involved in the criminal legal system a “criminal”—a word that implies a judgement on one’s character and fundamental worth as a human being—or an incarcerated person who committed a crime? Are the facilities in which 2.3 million Americans are locked up called prisons and jails, terms which help desensitize us to the cruelty of incarceration, or “human cages,” a term used by civil rights lawyer Alec Karakatsanis?

I recently spoke with Warren Wagner, a student organizer with #CareNotCops, a campaign calling for the University of Chicago to disband its private police force, one of the largest in the country. I asked him about the language he uses to describe those affected by the criminal legal system in his advocacy.

Wagner doesn’t use the terms “violent” and “non-violent” offenders. “Abolition rejects [the notion] that there are some people who simply can’t be out in society,” he said. “There aren’t ‘dangerous people’ and ‘safe people.’ We are harming each other in small ways all the time and being harmed in small ways all the time. There’s no amount of harm that says we’re giving up on you, we’re sending you away.”

Wagner did not once refer to incarcerated individuals as criminals. Instead, he opted for “those who have caused harm.”

“Crime is not the essence of one’s being,” he said.

Language matters not only in how we refer to those who are locked up, but also in how we differentiate among them. While the criminal legal system is built on conceptions of innocence and guilt, these conceptions play no part in Wagner’s own organizing.

“Abolition doesn’t really take into account deservedness,” he said. “We don’t think anyone deserves to be in prison or deserves to be arrested. That’s not a framework that’s helpful to anyone individually and certainly not to society. That’s only a vision of punitive justice.”

For Wagner, using the language of guilt and innocence to evaluate who should be in prison is not only unnecessary, but harmful. “Some people have harmed deeply, and others have harmed less deeply, but none of that alters your worth as a human,” he explained. “We believe that it’s a crisis that anyone is subjected to the conditions of the prison or to policing. It’s not made any less of a crisis if you’ve harmed people deeply in the past.”

Language also matters deeply in terms of how we discuss various criminal justice reforms. Wagner drew a distinction between “reformist reforms,” reforms that attempt to make the criminal justice system less racist and punitive but in doing so, only further legitimize its racist and punitive machinery, and “non-reformist reforms,” which instead help shift power and resources away from the carceral state. For example, investing in enhanced body-worn-camera technology would be a reformist reform because it allocates more resources towards police departments, whereas reducing police budgets would be a non-reformist reform.

In a nutshell, “if it doesn’t take power or money away from policing or prisons or other carceral institutions, it’s probably a reformist-reform,” Wagner said. Abolitionists like himself do not support these reformist-reforms.

Karakatsanis is similarly skeptical of the language surrounding criminal justice “reform.” In his book, Usual Cruelty: The Complicity of Lawyers in the Criminal Injustice System, he writes, “Much of the ‘criminal justice reform’ movement is superficial and deceptive. And it is therefore dangerous. It is designed to quell calls for genuine change while preserving the architecture of mass human caging.”

He explains that punishment bureaucrats—those who carry out punishment in the legal system—have exploited mantras of “criminal justice reform” to protect institutions of mass incarceration under the guise of reform, engaging in a kind of deception. “By making just enough tweaks to protect its perceived legitimacy,” he says, these individuals “obfuscate the difference between changes that will transform the system and tweaks that will curb only its most grotesque flourishes.”

So clearly, language matters. As journalists, we are charged with objectively reporting our findings, yet the words we choose convey our political stakes. Do I put “criminal justice system” in quotes? Do I label it the “criminal injustice system” instead as Karakatsanis does? Do I eliminate the word “criminal” from my reporter’s vocabulary?

It’s important that we ask these questions and reflect on our responsibility as journalists in interrogating the language of criminal justice. While language alone can’t change culture, it has power, one that should be leveraged. It’s important that we reflect on what we leverage it for.