BOBO-DIOULASSO, Burkina Faso — The barren, ruddy ground is pockmarked with holes as far as the eye can see—shallow, bowl-like holes filled with water and deceptively deep holes that drop like an elevator shaft straight down to black pits 50 feet below ground.

Imagine a giant meteor shower that pelts and then scorches the earth to leave nothing but holes and mounded dirt. And this is what you'd have, except that the destruction here comes not from nature but from men, women and children, clawing, digging and scraping for gold.

Here at Fandjora, a small-scale surface mine about 40 kilometers from the provincial capital of Bobo-Dioulasso, more than 1,500 people are working the earth for their tiny share of $1,600-an-ounce gold. Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in the world, ranks fourth in Africa in the production of gold. Much of the gold comes from small-scale mines, where untold numbers of children work with their families from dawn to dusk. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimated in a 2006 report that 30 to 50 percent of the people working in small-scale mines in the African Sahel, which includes Burkina Faso and neighboring Niger, are younger than eighteen. Some as young as 3 work alongside their parents.

Little children squat on the ground filling bowls with dirt and rock. They scamper around the deep pits without even a sideways glance. The sound of scraping and of metal against rock creates a constant din, as workers break up the surface with primitive hand-made hoes and picks. The air is thick with dust that turns dark arms and faces a powdery white. It is hard to breathe this dusty air, but no one wears a mask.

The U.S. Department of Labor and the ILO consider mining one of the worst forms of child labor because of the immediate risks and long-term health problems caused by back-breaking manual labor and exposure to dust, toxic chemicals and heavy metals.

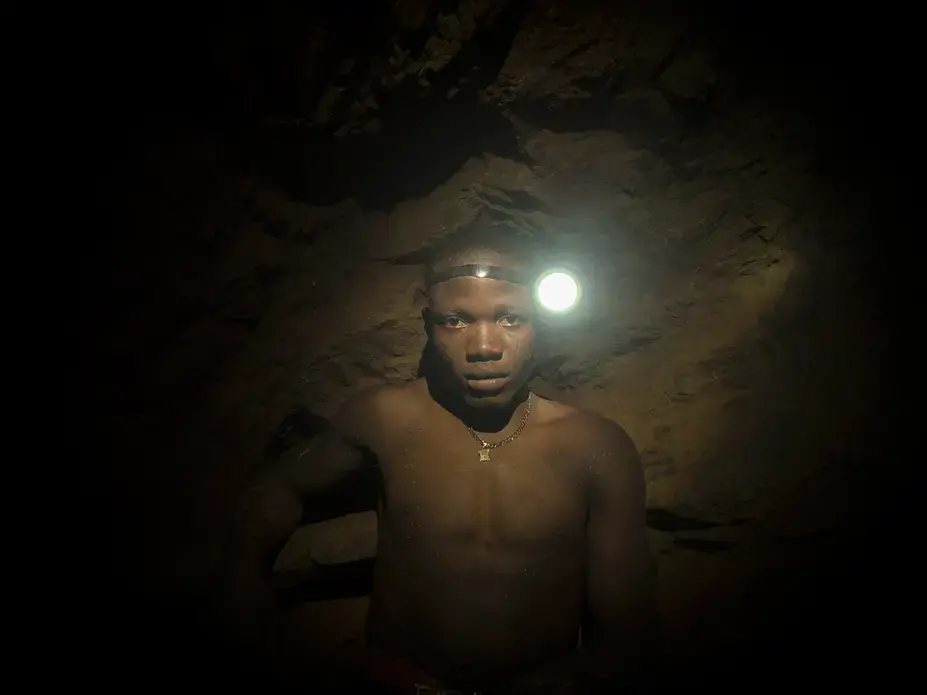

Older boys go down the pits to chip ore from the walls. There are ropes for the buckets of ore but not for the boys, who scramble up and down over timbers, finding footholds and handholds in the dirt walls. A lost grip and the plunge to the bottom is 30 or 40 feet.

The deeper the miners dig, the more narrow and claustrophobic the pits become until the crevices are large enough only for smaller adults or children. The children wear flashlights strapped to their heads as they chink away at the rock, wedged into spaces no larger than a common trash can. They work ceaselessly, their faces blank of all emotion, their eyes dull, even glassy. Their hands are gnarled, calloused and grotesquely large for such small bodies—the hands of 50-year-old men on the bodies of small children. Their hands, as much as their eyes, tell the stories of their hard lives.

At midday, the miners break for lunch, usually a bowl of rice and peas and perhaps a little pork, eaten by hand from a communal cooking pot. The children, who have been working since sunup, literally crash and lie down to sleep in the dirt, beside a cook fire, even across a timber in a mine.

After a short break, the digging resumes, to continue until dark. In an established gold field, such as this one, the holes are dug ever closer together. Occasionally, the digging undermines an existing pit and the walls collapse. In January 2013, one miner died and another was seriously injured in a mine near Fofora when their pit caved in.

For the most part, the children are with their parents, doing what they can to contribute to the family's take. Powder, grit, pebbles, rock are all bagged by type and size, weighed and sent on for processing at another site where there is heavy machinery. A foreman records the quantities of material produced by each miner. When the gold is processed and sold, a tiny percentage makes its way back down to the miners and their families, anywhere from about $5 to a princely $40 a day.

The Kouékowéra mine near Gaoua is older and more established than the Fandjora field. The pits are larger and braced with timbers. Mining here supports an entire village.

Karim Sawadogo has come to Kouékowéra with his uncle to work in the gold camp. The boy says that he thinks that he is 9 years old but that he isn't sure. A man nearby overhears and shouts that the boy is 16. Other men chuckle. It is an old joke. Child labor is illegal in Burkina Faso, but in the remote areas, enforcement is spotty.

Karim, like so many of the boys in the gold field, is slight but muscular and no stranger to work. Before the gold camp, he was a goat herder near his home in northern Burkina Faso. He has been to school but only a little. In the camp, he cooks, fetches water and works down in the mines, chipping rocks and filling baskets that are hauled to the top.

Speaking through a translator in his native dialect, Karim smiles when he is asked what he wants to do with his life. "I came here to make money," he says. "My dream is to make enough money, so I don't have to do this anymore."