Last Saturday, shoppers at a supermarket in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, filled their carts with groceries and non-perishable items, preparing for the next day's elections as one might for a hurricane. There was good reason to fear that disorder might follow the vote: after the country's elected President, Manuel Zelaya, was deposed in a military coup in June of 2009, the Army patrolled the streets in the months leading up to a contested election that November, which brought the conservative National Party into office.

There were eight Presidential candidates on the ballot—reflecting a degree of popular discontent with the country's two traditional ruling parties, the National Party and the Liberal Party—and the frontrunners held radically divergent ideological positions. Juan Orlando Hernández, of the National Party, campaigned on a platform of law and order, promising to reduce the country's homicide rate, which last year was the highest in the world. The newly formed left-wing Liberty and Refoundation Party (known as Libre), is led by Xiomara Castro, the wife of the deposed President, who promised to rewrite the country's constitution and initiate significant land reforms in an attempt to lift Hondurans from poverty—essentially picking up where Zelaya left off, before his radical tilt and increasingly cozy relationship with Hugo Chávez led to his ouster.

The first results, reported hours after polls closed on Sunday, November 24th, favored the National Party. With eighty per cent of the votes counted, Hernández had thirty-six per cent of the vote; Castro trailed with twenty-nine per cent. The Liberal Party's candidate, Mauricio Villeda, was in third place, while the upstart Anti-Corruption Party, led by the television personality Salvador Nasralla, trailed in fourth. Both Castro and Hernández declared victory. On Monday, the Libre Party held a press conference at the a hotel in Tegucigalpa. Zelaya, the former President, addressed reporters and a large group of party members, insisting there had been widespread fraud at polling booths.

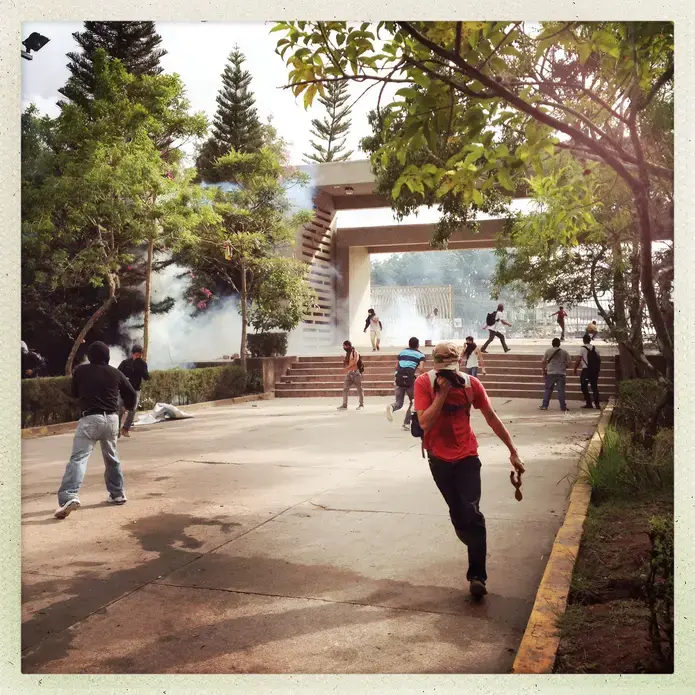

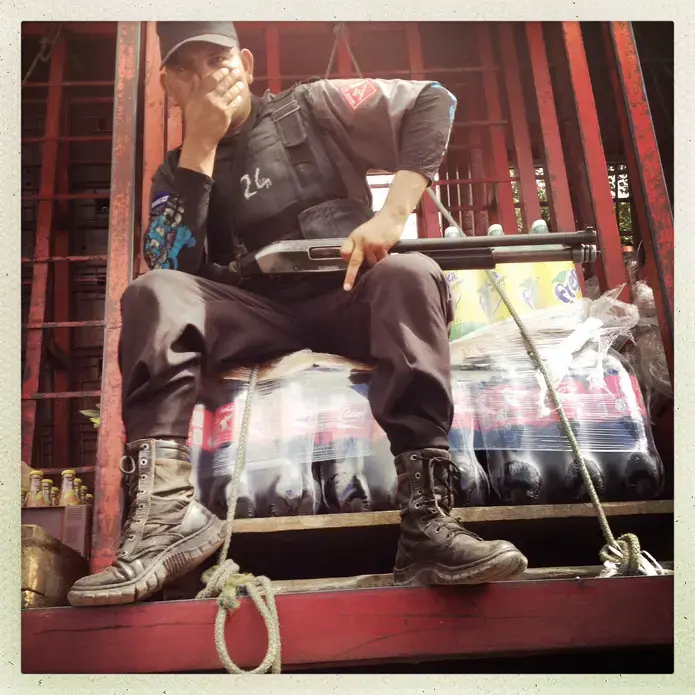

On Tuesday, with most Hondurans returning to work and school, students began rallying at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras. Undergrads watched as protesters marched through the school's property. By afternoon, the police arrived in riot gear. A police truck lumbered up a major thoroughfare, firing its water cannon, while canisters of tear gas arced through the air. The demonstrators tired themselves out throwing rocks at the police.

At the university, one electoral volunteer claimed that he and the other workers at a rural polling station in Bajo Aguán had been forced to flee after polls were closed by armed National Party members and police, preventing the tabulation of votes. His story, impossible to verify, had already spread widely. In some circles, it was eagerly accepted, along with other such anecdotes, as conclusive evidence of the fraud Castro and Zelaya had alleged.

International observers, including the Organization of American States and the European Union, deemed the vote transparent; there is no expectation that the election will be overturned. But the country's ideological divide has widened further. On Sunday, Castro and Zelaya led thousands of protesters in a peaceful march through the capital, carrying the body of a Libre supporter who had been shot to death the day before. "If they do not accept our complaint, we will appeal to all the levels permitted by law," Zelaya said. "And if they don't resolve it, we will also appeal to international treaties."

Education Resource

Journalists Jeremy Relph and Dominic Bracco II on Reporting in Honduras

Writer Jeremy Relph and photojournalist Dominic Bracco II traveled to Honduras to report on the...