THREE YEARS AGO, Laura Gaither and her family spent their summer vacation in Panama City Beach, Florida. One afternoon, while rinsing sand off her feet, the 35-year-old Alabama resident felt something biting her legs and noticed tiny black bugs on her skin. Gaither brushed them away, and later, when she described the bites to local residents, they told her that she had likely been bitten by sand flies.

Three of Gaither’s five kids had been bitten, too, but she didn’t worry. The marks on their legs and arms looked like ant or mosquito bites, which can cause burning and itching, but usually subside within a week.

But about two weeks later, back at home, Gaither noticed that the bites had morphed into small open wounds. They worsened over the next couple of weeks, but when she took her children to their pediatrician, “he just chalked it up to eczema,” Gaither said. Eventually Gaither took her young daughter, whose condition was the most concerning, to the emergency room at Children’s of Alabama, where she was tested for fungal and bacterial infections. The results came back negative, and the anti-fungal and steroid topical creams the doctors prescribed proved ineffective. Meanwhile, the ulcers kept growing larger and more painful.

Gaither started doing her own research and learned about a flesh-eating disease called cutaneous leishmaniasis (pronounced leash-ma-NYE-a-sis). This skin disease is caused by more than 20 species of Leishmania parasites. It can be transmitted to humans through the bite of some sand flies after the flies themselves have been infected by animals — usually rodents in the United States — whose blood the insects feed on. Sand flies thrive in hot sandy beaches and in rural areas, and they had been particularly abundant in Florida in 2018, Gaither was told during her visit.

Leishmaniasis, Gaither learned, is common in tropical and subtropical countries like Brazil, Mexico, and India. Looking through peer-reviewed papers, she saw pictures of leishmaniasis wounds that looked a lot like her own: crater-like ulcers coated with a thick, yellowish pus.

During the visits with her children’s pediatrician and in the ER, Gaither asked her doctors about the parasite. They dismissed the possibility that the family might have contracted a tropical disease without traveling abroad, she said. “Nobody would even entertain what I was saying.” That is, until the wound on Gaither’s knee worsened and, armed with research papers, she convinced her own physician to test a biopsy for leishmaniasis. The results were inconclusive.

Fortunately, by this time the children’s wounds had begun to heal. Three months after they appeared, the ulcers completely cleared up, leaving Gaither to wonder what really caused them. While her family’s ordeal has ended, scientists say the storyof leishmaniasis in the U.S. is just beginning.

“It’s a pretty striking difference for a disease that we used to think of as limited to South America now extending as far north as Canada,” McIlwee said, “potentially within the next several decades.”

Americans, it turns out, can be exposed to Leishmania parasites without leaving the country. The parasites are currently endemic in Texas and Oklahoma, and new studies suggest that they might be present in other states, including Florida. While reported cases of leishmaniasiscontracted in the U.S. are currently negligible, they may soon be on the rise: As climate change pushes rodent and sand fly habitat northward, scientists caution that in the future, an increasing number of U.S. residents could be exposed to different varieties of the flesh-eating parasite.

Some strains of Leishmania parasites can be life-threatening. The one currently present in the U.S., Leishmania mexicana, induces milder symptoms and over time, can heal on its own. But if doctors fail to recognize it, or overreact to it, damages caused by wrong therapies and unnecessary toxic systemic medication can cause more harm than the disease itself.

Bridget McIlwee, an Illinois-based dermatologist, has treated patients who contracted leishmaniasis in Texas. She wants her colleagues to be more aware of the parasite’s expansion into the U.S. “It’s a pretty striking difference for a disease that we used to think of as limited to South America now extending as far north as Canada,” she said, “potentially within the next several decades.”

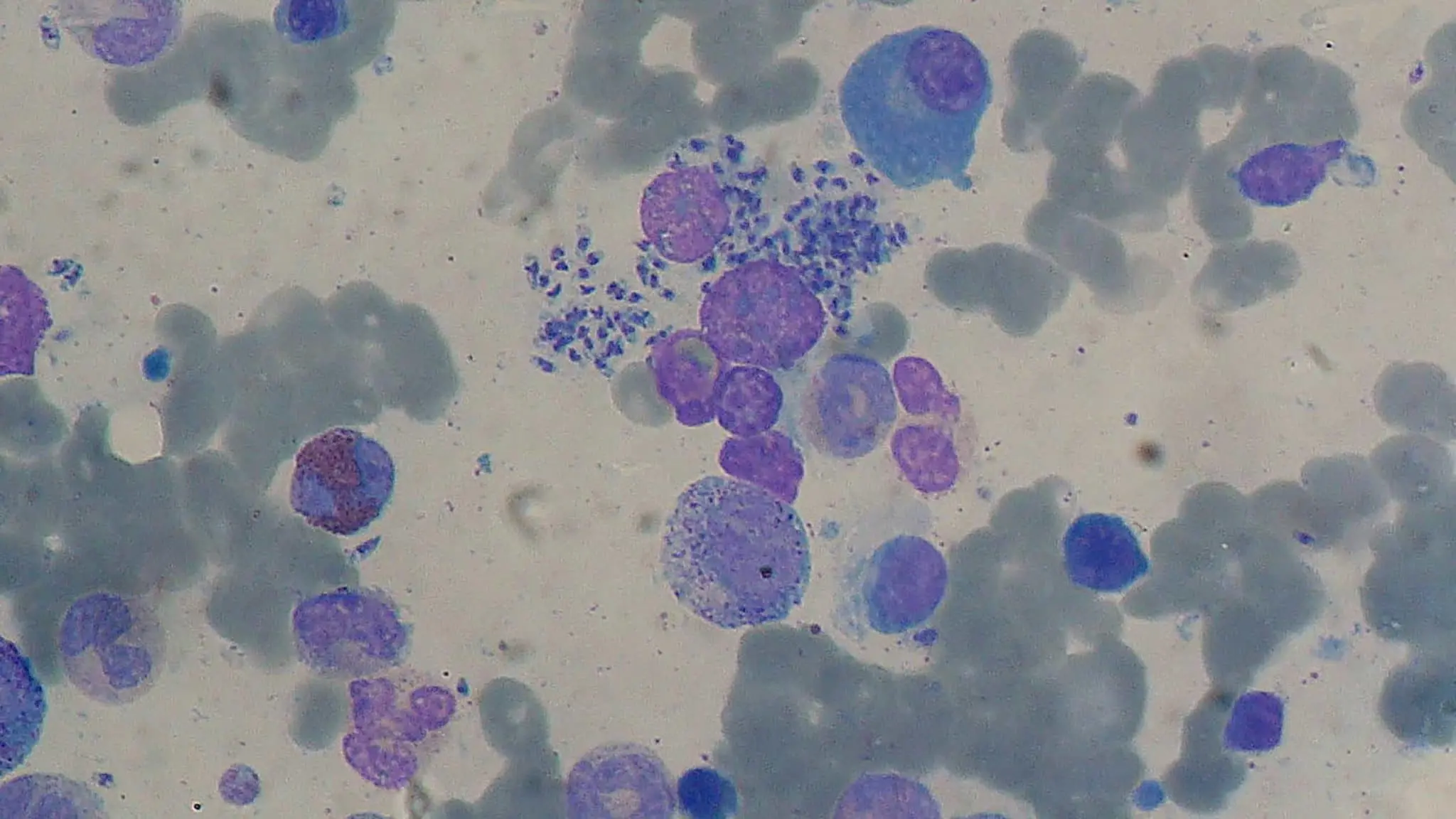

EVERY YEAR, between 1.5 to 2 million people worldwide contract leishmaniasis, and around 70,000 die from it, mostly in poor rural areas. The most dangerous Leishmania strains, such as infantum and donovani, don’t just eat a person’s skin, they also infect the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, leading to death if not treated. Drugs like miltefosine and amphotericin B, used to cure these strains of Leishmaniasis, are expensive or toxic, and not much funding goes into researching and developing better treatments. In 2007, the World Health Organization added leishmaniasisto the list of neglected tropical diseases, which mainly affect the word’s poor and do not receive much attention.

While Leishmania parasites are present in about 90 countries, the symptoms of an infection vary by strain. The mexicana strain, typically found in Mexico and Central America, causes skin sores that can sometimes take years to heal and leave ugly scars. Others, like panamensis, mostly found in Panama and Colombia, attack the mucous membranes that line the inside of the nose and mouth, disfiguring people permanently.

Most leishmaniasis cases treated in the U.S. are linked to international travel. But there is evidence that an increasing number of people are infected in the U.S., likely by Leishmania mexicana. Between 1903 and 1996, only 27 cases of locally-acquired leishmaniasis were reported in the U.S. Then, in just 10 years between 2007 and 2017, 41 new local cases were reported.

But those numbers might not reflect extent of the problem, said McIlwee. Currently, Texas is the only state that requires health professionals to report leishmaniasis cases to the state’s health department. Without a federal reporting requirement, she said, it is “a little bit tough to say exactly” how many cases occur across the country each year.

While the true U.S. case count is certainly lower than in tropical regions, a 2010 study sounded an alarm. Scientists from the University of Texas at Austin and the National Autonomous University of Mexico spent hours doing fieldwork, catching sand flies and rodents in Texas and northern Mexico to pinpoint the species’ range. They then incorporated this data into computer models that map ecological niches — the highly specific environmental conditions in which these sand flies can sustain a population — and also took into account how temperatures across North America will be affected by climate change. This allowed the international team to predict the geographical expansion of sand flies and Leishmania-infected rodents.

According to the models, by 2020, the rodent-fly-parasite habitat was expected to extend to Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, and Missouri. By 2080, the results showed the habitat stretching as far north as southern Canada, exposing nearly 27 million North Americans to the disease.

“Climate change has a strong link with the emergence of zoonotic disease,” said Víctor Sánchez-Cordero, a study author and an ecology professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “There is the possibility that there will soon be cases of human leishmaniasis in the U.S. where before [they] did not exist.” In fact, at least one case has already been reported as far north as North Dakota.

Sahotra Sarkar, another author on the study and professor of integrative biology at the University of Texas at Austin, said that the team needs a few more years to gather the data that would confirm the accuracy of their modeling. But based on unpublished field data and citizen science reports, he believes the study’s predictions for 2020 were correct.

Climate change is probably not the only factor driving the species’ habitat expansion, said Sarkar. Human development can also play a role. When wild areas, like forests or savannas, are eliminated, the species living there will migrate. This can bring the migrating species into closer contact with people, increasing the risk for diseases to spill over into human populations.

Climate change is expanding the range of animals that carry Leishmania parasites in other countries, too. “The real spread of the disease is underestimated,” said Camila González Rosas, a biology professor at the University of the Andes in Colombia. Her own research has demonstrated that a warming climate is pushing these vector species to higher altitudes in Colombia.

Rojelio Mejia, an infectious disease physician at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, said that a couple of years ago he treated a patient who had traveled to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. While there, the patient contracted leishmaniasis, not the familiar local strain, but braziliensis, which is dominant farther south. According to Mejia, that strain, which is even more aggressive and disfiguring than mexicana, was not supposed to be in Mexico.

“So you can just start saying, if we continue climate change, will braziliensis continue to climb up?” Mejia wonders. If the Brazilian strain does head north, it will create a more significant public health problem than the one the U.S. is currently dealing with.

IN 2018, McIlwee co-authored a study that found 41 human cases of leishmaniasis contracted in the U.S. since 2007, most of them occurring in Texas. Most physicians, the paper contended, are not aware that the disease can be contracted within the country and that they only consider it as a diagnosis if a patient has traveled abroad.

“They’re not thinking about it when they’re looking at a skin lesion,” McIlwee said. Physicians have been known to mistake the wounds for symptoms of a bacterial infection; this misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatments, such as a prescription for antibiotics, which may inhibit the body’s immune system, leaving the parasite to reproduce unchecked.

Over-treatment can also be a problem. “When most medical students are learning about leishmaniasis in medical textbooks, they’re seeing really impressive, ulcerated, deforming lesions,” McIlwee said. These cases sometimes require treatments that can cause significant side-effects, but Leishmania mexicana, if caught on time, can be defeated with a gentler approach.

Mexican Mayan healers, who have been dealing with the illness — known locally as úlcera de los chicleros — for millennia, may have found an even less invasive way to treat the disease: an herb paste applied to the ulcer for one to two weeks.

“The cases that I saw were all very subtle. They weren’t very advanced, they didn’t have a lot of damage to the surrounding skin or anything like that. And all of them could be treated locally,” McIlwee said, recalling her days as a dermatology resident at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. There, she successfully cured a patient with an ear lesion by applying liquid nitrogen. And she’s not the only one: Dustin Wilkes, a dermatologist in Weatherford, Texas, recently used the same approach to successfully treat a patient with three leishmaniasis lesions on his left shoulder. Prior to seeing Wilkes, the 65-year-old had declined a prescription for a harsh medication from a different doctor.

For those in other countries battling more aggressive Leishmania strains, there is hope for both ancient and modern approaches. Mexican Mayan healers, who have been dealing with the illness — known locally as úlcera de los chicleros — for millennia, may have found an even less invasive way to treat the disease: an herb paste applied to the ulcer for one to two weeks. In a study published in 2018 in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology, researchers found that the plant, known as Cleoserrata serrata, mostly found in southern Mexico, significantly inhibits parasite growth.

Additionally, Abhay Satoskar, a pathology professor at the Ohio State University is working on a vaccine, which he says looks “very promising.” The vaccine is slated to begin clinical trials next year, and plans are being laid by manufacturers in India for its commercial production, Satoskar said.

While physicians and researchers grapple with the flesh-eating parasite, scientists say additional challenges are on the horizon. As climate change pushes disease-vector species north, said McIlwee, “leishmaniasis is just one of a number of different diseases that we’re going to see more of.”

- View this story on Scientific American

- View this story on Popular Science

- View this story on NPR

- View this story on Medscape

- View this story on Spokane Public Radio

- View this story on The Atlantic