For the first time, BuzzFeed News can reveal the full capacity of China's previously secret network of prisons and detention camps in Xinjiang: enough space to detain more than 1 million people.

BuzzFeed News calculated the floor areas of 347 compounds bearing the hallmarks of prisons and internment camps in the region and compared them to China’s own prison and detention construction standards, which lay out how much space is needed for each person detained or imprisoned.

Earlier estimates, including one extrapolated from three-year-old leaked government data, have suggested that a total of more than a million Muslims have been detained or imprisoned over the last five years, with an unknown number released during that time. Our unprecedented analysis goes further, showing that China has built space to lock up at least 1.01 million people in Xinjiang at the same time.

That’s enough space to detain or incarcerate more than 1 in every 25 residents of Xinjiang simultaneously — a figure seven times higher than the criminal detention capacity of the United States, the country with the highest official incarceration rate in the world.

Even this extraordinary capacity is very likely an underestimate, for a simple reason: It does not take into account the suffocating overcrowding that many former Xinjiang detainees have described in interviews.

Since last year, BuzzFeed News has exposed how China feverishly constructed a permanent mass detention infrastructure in Xinjiang to help carry out its draconian campaign of detention, surveillance, forced labor, and repression targeting Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities. This new analysis is the most clear and complete picture to date of the system’s scale and capacity.

The findings reflect what researchers, UN officials, and Western governments have long held: that China’s detention campaign in Xinjiang is the largest targeting a religious minority since the Nazi camps during World War II.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this story sent to the Chinese Consulate-General in New York. It has previously called estimates of a million Muslims detained in Xinjiang a “groundless lie,” and has said that its facilities in Xinjiang are “vocational education and training centers” designed to “root out extreme thoughts.” These centers, a top Xinjiang government official said in 2018, are meant “to get rid of the environment and soil that breeds terrorism and religious extremism and stop violent terrorist activities from happening.”

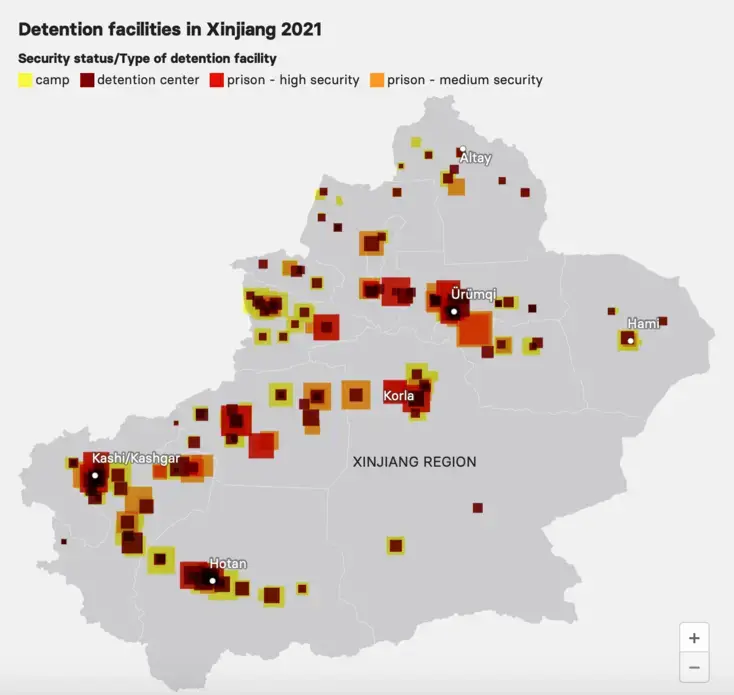

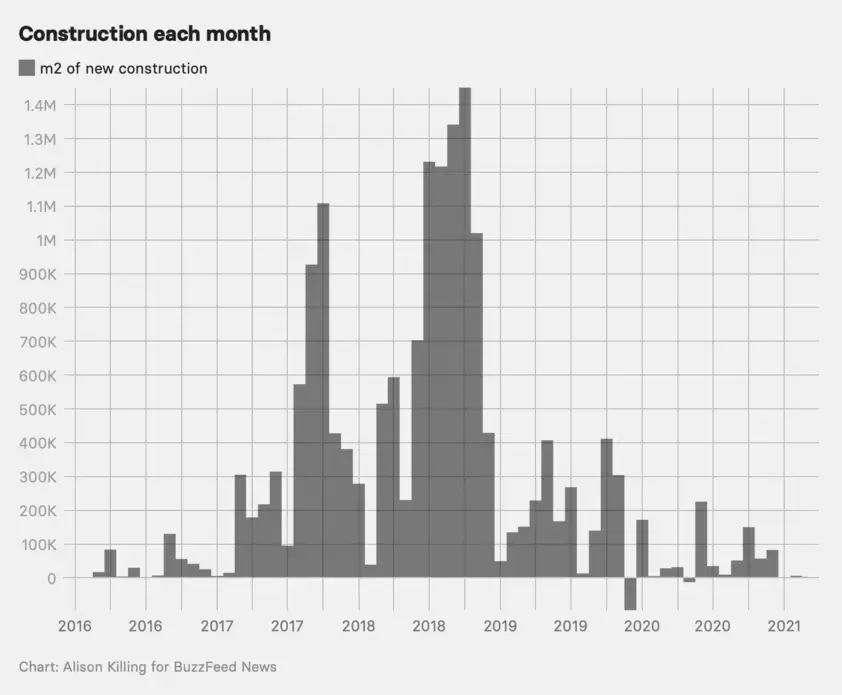

The campaign to lock up Muslims in Xinjiang started in 2016 as a scramble, with schools and other public buildings turned into makeshift detention centers. But it quickly evolved into a sophisticated network of newly constructed prisons and camps that blankets almost every corner of the sparsely populated but vast Xinjiang region, which is about the same size as Alaska.

The course of camp and prison construction suggests that the government carefully orchestrated the campaign. The pattern of new detention compounds neatly fits the geography of counties and prefectures across Xinjiang, with a camp and detention center in most counties and a prison or two per prefecture. As the new, high-security detention centers were being built — a process that takes about a year from idea to completion — the Chinese government commandeered schools, hospitals, and apartment buildings and quickly converted them into makeshift camps. This twin process allowed Beijing to immediately detain hundreds of thousands of Muslims until its vast new detention infrastructure was complete.

BuzzFeed News examined only compounds that were newly built or saw significant construction work since 2016. Using satellite images, documents, and testimony, we first identified 268 facilities bearing the hallmarks of camps and prisons last August; this new analysis includes those as well as 79 more that have since been discovered by BuzzFeed News and other organizations.

By April 2021, the facilities examined by BuzzFeed News had a combined area of more than 206 million square feet, or about 19.2 million square meters, which would cover a third of the island of Manhattan. Most of that growth came in 2017 and 2018.

BuzzFeed News obtained public documents that set forth construction standards and show how the government plans its prisons in meticulous detail, from the size of the bars on the windows to the spacing of the lights along the perimeter to the height of the watchtowers. Cells are designed to hold between eight and 16 people, with between 5 and 7 square meters per person. Construction typically takes between four and six months.

The documents are a hard copy of prison regulations, edited by the Chinese Ministry of Justice and published by a Chinese state publisher in 2010, as well as a set of 2013 regulations for detention centers. It is not clear whether the government has revised them since then, but a number of the details in the documents match what can be seen in satellite images of the newly built facilities, including the layers of fencing on either side of the prison perimeter walls and the open-air yards adjacent to each detention center cell. Images from the websites of Chinese companies that build and supply prisons corroborate additional details. One manufacturer’s website shows the prescribed anti-climb fencing, razor wire, beds, cell doors, prison entrance gates, and interrogation chairs.

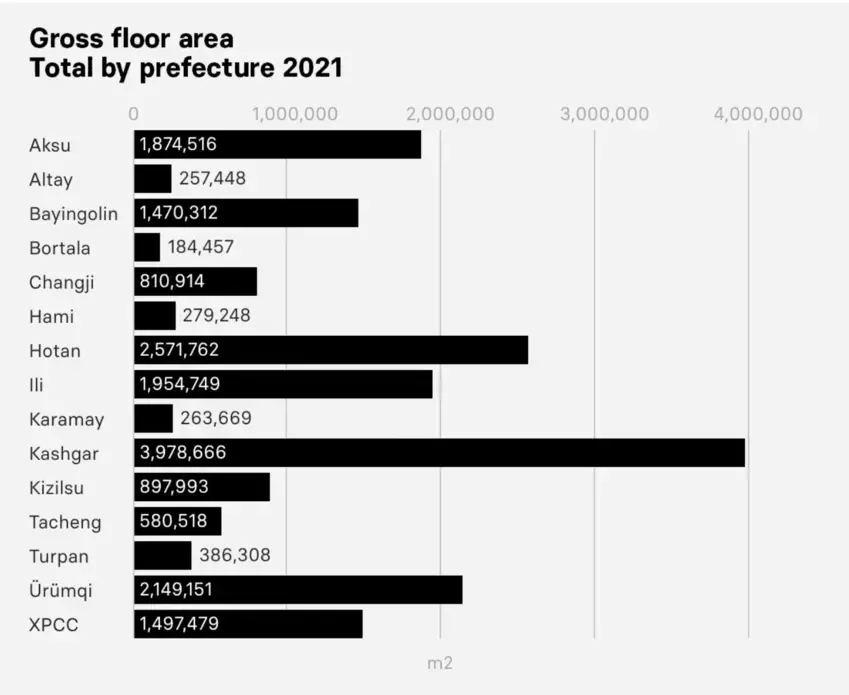

The BuzzFeed News analysis found that by the standards outlined in the document, there is space to detain 1,014,883 people across Xinjiang. That figure does not include the more than 100 other prisons and detention centers that were built before 2016 and are likely still in operation.

Dozens of former detainees have described gross overcrowding in Xinjiang’s prisons and camps, raising the specter that the Chinese government could cram far more people into its sprawling detention system. Last year, a BuzzFeed News investigation of an internment camp in the mountain town of Mongolküre found cells that by Chinese prison standards should only hold up to four people actually held as many as 10. Some remembered being forced to sleep in shifts because of a lack of beds, or even to sleep side by side on single cots. Whether overcrowding continues to occur is less clear, because most of the former detainees who have been able to escape China and describe their experiences were locked up and released early on in the anti-Muslim crackdown.

About half of Xinjiang’s population is made up of Han Chinese people, who are China’s dominant ethnic group. But in some areas of the region, particularly in the south, Uyghurs make up a greater share of residents. Areas with higher Uyghur populations, such as Kashgar, Hotan, and Kizilsu, tend to have high amounts of detention space, the analysis found.

The true total number of people who have been locked up during the campaign remains a secret. The most commonly cited estimate of 1 million comes in large part from a 2018 analysis by the scholar Adrian Zenz and is based on a leaked database of detainee numbers for 65% of Xinjiang’s counties. Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an advocacy group, published a similar estimate that year based on interviews with Uyghur exiles. A UN committee gave a similar estimate that year citing “credible reports,” and the US State Department said a week later that China could be detaining “millions” of Muslims in Xinjiang. How much the number of detainees may have risen since 2018 is unknown — but the Chinese government continued to expand its capacity during that time. One new detention complex is currently under construction, and four existing ones are adding new buildings, allowing the government to put even more people behind bars.

Ahmati, a Uyghur man from Kashgar, first saw police checkpoints springing up on the highways between cities and police vans that stopped people in the streets in 2016. He felt irritated that the government was frittering away his tax money on weeding out a handful of extremists. He ran a successful business and had good connections in the Communist Party. He didn’t visit any foreign websites, and he preferred Chinese apps like WeChat and QQ to talk to his friends instead of banned apps like WhatsApp. The whole thing, he thought, had nothing to do with him.

But a lightbulb went off when he started to hear and read about Chinese leaders using wartime analogies to describe the fight against “extremism” in Xinjiang — the government has justified its policies targeting Muslims as efforts to protect national security and stamp out terrorism. Initially he was bewildered. “I thought, There aren’t any foreign armies here. There are no enemies,” he said. “Then I understood. The enemy was us.” He asked to be identified by Ahmati, his nickname, to protect himself and family members still in China.

By the middle of 2016, Ahmati said, so many Uyghurs were being rounded up that people were starting to panic. Nobody knew what happened inside the camps — just that people were disappearing inside them at a frightening pace. Before the weather had turned cold, the stores were completely sold out of thermal underwear because people assumed the camps would be freezing during the coming winter. Mosques were empty, and Ahmati threw away his collection of religious texts. Others, he heard, had thrown theirs in the Kashgar River, watching the pages curl in the water as they floated downstream.

“Before this, Uyghurs were a united people. We were close-knit,” Ahmati said. But after the crackdown started, he had tried to avoid anyone whose relatives had been detained. “It broke the trust between people,” Ahmati said. “You couldn't visit with people anymore.”

Ahmati left Kashgar and Xinjiang in 2017. That same year, he said, his two older brothers were both sent to camps.

In the early months of the campaign, Kashgar and other cities in Xinjiang’s Uyghur heartland, like Hotan and Aksu, seemed to be the government’s focus. Satellite images show camp and prison construction began early there, and some of the first anecdotal evidence of the existence of camps came from these places, which lie in the south of the region. But soon China’s campaign extended to every corner of the region, including areas with large populations of Han Chinese people, where a crackdown might be less expected.

The speed of prison construction shocked people who were born and raised in Xinjiang. Eysa Imin grew up in a small village outside Korla, an ancient city that lies on the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Korla, Xinjiang’s second-largest city, is famous for its sweet, fragrant pears, and visitors often carry box loads back home on the train. It is also known as a destination for Han Chinese migrants to the region.

Imin grew up in a big family, with three sisters and three brothers, though one of his sisters died young. Later, he would look back on those playful childhood years in the countryside with a painful sort of nostalgia. In 2003, Imin married and moved to Korla. Years later, after settling into life in the city, he started a business with a friend importing a bottled health drink from Malaysia. He relished the chance to travel overseas.

But like other Uyghurs, he quickly discovered that having spent time abroad, especially in Muslim-majority countries, made him an object of suspicion for government authorities. In October 2015, he was detained by police at the airport in Urumqi and taken to a detention center in Korla. State security officials interrogated him for hours about his contacts overseas and whether he had taken any actions that could threaten the state, he said.

The mass detention campaign had not yet come into full swing, and the compound where he was locked up was an old detention center, with space for just over 500 people. Still, life in detention was strange and disorienting. In the mornings before breakfast, the prisoners had to sing patriotic songs, like “Without the Communist Party, There Is No New China.” There were Han Chinese people detained there too, ones who were accused of crimes like embezzling money or assault. Imin wondered why he was there, since he had never committed such a crime, and nobody had accused him of having done so. In interrogations, police at the detention center asked if he had watched videos on YouTube or Facebook, platforms that are banned in China. He told them he hadn’t.

After 43 days, Imin was released. Police gave him a document, which he shared with BuzzFeed News, stating that he had been detained for endangering national security, but that he was being released with all charges dropped. He tried to put the experience behind him, and in January, he moved to Turkey with his wife and young children.

Imin kept in touch with relatives and friends in Korla. Everyone knew about the construction of new prisons — and he did too, because it was something that people talked about. But he had been released and had a document to prove it. So it had little to do with him, he thought.

Imin also figured that Korla’s large Han Chinese population would spare it from the worst of the Chinese government’s excesses. He didn’t think twice about returning from Turkey for a visit.

Arriving back in town, he was stunned to see dozens of new checkpoints and mobile police units dotting the streets. He contacted a police officer he knew, who informed him his name was on a government blacklist because he had lived in Turkey. He tried to lie low at his in-laws’ home.

But almost overnight, it had become impossible to avoid the authorities. “I realized that whether you’re in a bus or a car, when you pass through checkpoints, they only ask Uyghurs to get out of the vehicles so they can check their IDs and search them,” he said. “Han Chinese people stayed in their cars.”

“I couldn’t even go out to buy a bottle of milk without needing my ID to scan everywhere,” he added. “It was a big change.”

He was detained again in March 2017, just months after the government’s construction campaign had begun, and he was sent to a camp in Korla — another older facility, capable of holding only about 200 people. This time, because so many Uyghurs were being detained, the conditions were much worse. None of the other people detained were Han Chinese — there were only other Muslim minorities like him. To his surprise, he recognized some of his cellmates from his school days.

The cell was crowded, and because the men were seldom allowed to bathe, it smelled so bad that guards would use the collars of their shirts to cover their noses when they came in to open a small window. After a few days, Imin felt a wave of disgust when he realized he had gotten so used to the stench that he hardly noticed it anymore. It was freezing cold, and the guards would give the detainees a bucket of hot water that they would pass between each other, trying to warm their hands by holding it in their laps.

On one occasion, Imin and his cellmates were allowed to go outside, to a small balcony. “I didn’t see the sun,” he said, “but I felt it on my face — just that sliver of sun that felt so good.”

By April 2017, Imin was released from detention for the last time, after about a month. He believes it’s because he agreed to spy on other Uyghurs when he returned to Turkey — something he says he never did. The small detention center where he was held was demolished the following year, satellite images show. But as older facilities in Korla were being destroyed, the government was ramping up construction on newer, more permanent facilities in the area.

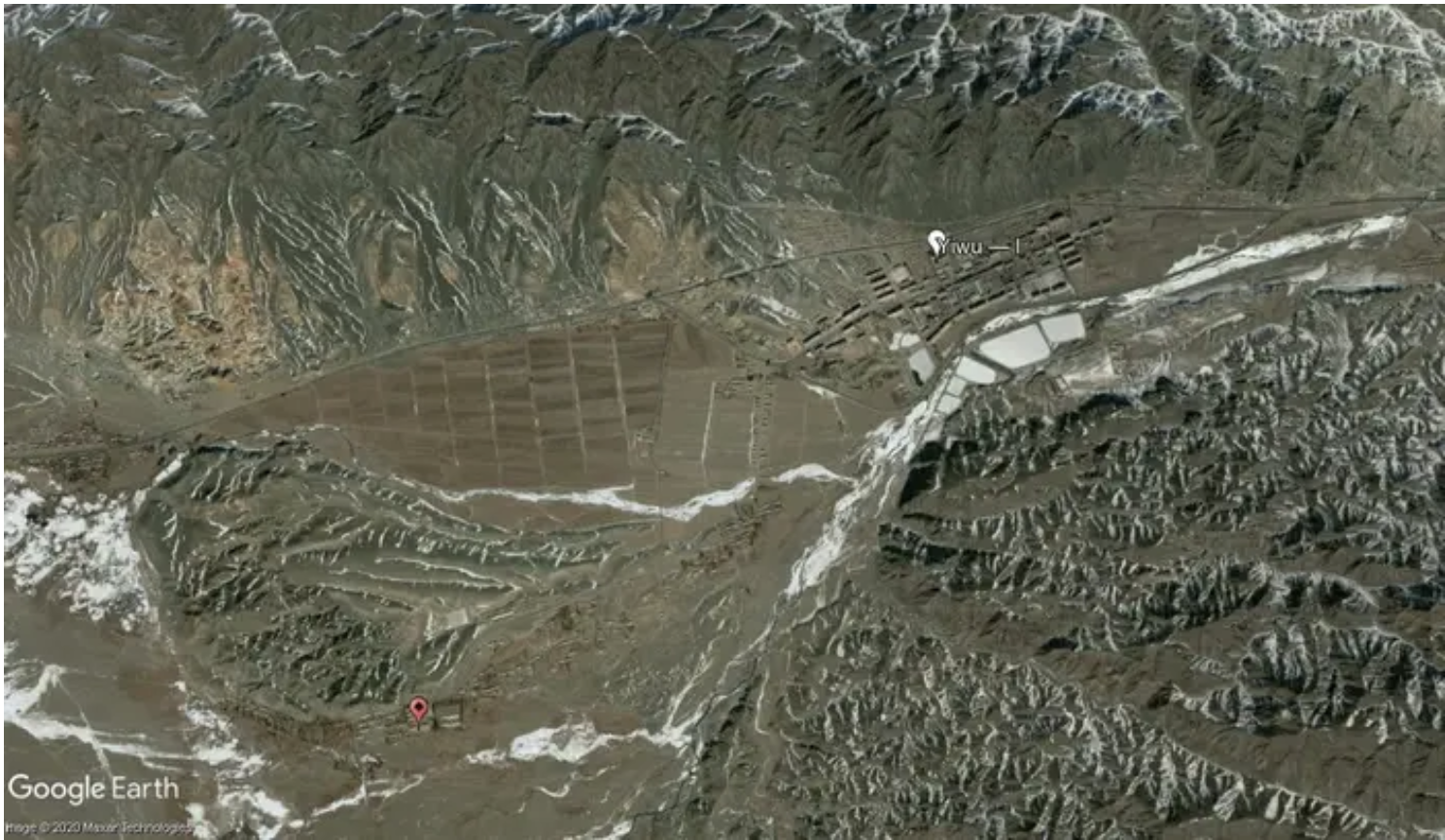

By summer 2017, satellite images show, a new detention center had been added to a steadily growing complex with multiple facilities on Korla’s eastern outskirts. A high-security prison — recognizable by the double layers of barbed wire fencing on both sides of its perimeter wall and with its status confirmed by tender documents — had, by the end of 2017, grown to the size of 39 American football fields. Altogether, the complex had space for 7,312 people.

The government still was not finished building in Korla.

On Feb. 20, 2018, during China’s weeklong Lunar New Year holiday, workers broke ground on the Korla Vocational Skills Education and Training Center, a new purpose-built internment camp at the southernmost end of the area.

A photograph taken in mid-April shows local party officials standing at the entrance to the construction site wearing hard hats, the site’s arched entrance in the background.

Satellite imagery from March 2018 shows the site under construction, with eight identical dormitory buildings, offices, a canteen, and a “correction center,” as well as other support facilities. The plans scheduled just 69 days for the construction of the camp, and a budget of 453 million yuan (around $70 million), according to a state media report uncovered by the Canada-based researcher Shawn Zhang. By July, the camp was ready to begin detaining people.

A little more than a year later, the entire complex had grown even further, with a second detention center built and a series of new buildings added to both the medium- and high-security prisons. Altogether, the entire complex can now hold nearly 25,000 people without factoring in overcrowding — a ninefold increase compared to 2016.

Now in Germany after his final release, Imin finds it difficult to get news about his family because of the Chinese government’s surveillance of digital communications within the country. He often lies awake at night, he says, “psychologically suffering.” His mind frequently travels back to China, wondering about his brothers and sisters. All five have vanished, he believes into prisons or camps. He thinks often about one of his brothers who had become religious, wearing a long beard and praying often. He knew authorities had targeted him for detention. He didn’t know if he’d ever see him, or any of his siblings, again.

In Germany, strange things remind Imin of home, like packets of dried red chili peppers. While in the camp, one of the men who had spent time in a prison had told him that inmates had to clean the chilis and stuff them into plastic packets for sale. He had never seen it happen, but the story stayed with him. He had heard once that chilis like those were exported to Germany.

He didn’t know whether that was true. But now, looking at the chilis made him feel sick.

“I thought that maybe without knowing,” he said, “I might have eaten something that was made with the blood of my brother.”

To view interactive maps click here.