Pat Uhlman lives across the street from Shubael Pond in Barnstable. The round pond is ringed by trees and — most days — crystal clear.

"It’s so beautiful," she said. "I get up in the morning, I open my drapes, and if the sun is already up, the pond is glistening."

But a couple of years ago, the glistening pond turned a milky green. It was a cyanobacteria bloom, known more commonly as "toxic algae." Toxic algal blooms can make people sick if they ingest the water and are especially dangerous for dogs and small children. Concerned, Uhlman paddled her kayak into the pond to see how far the algae had spread.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

"I kayaked around and I was leaving a trail — you could see where the kayak had cut through the slime," she said. "You feel almost scared, like, 'What is going on?' And that it's never going to clear up and that the pond is dying."

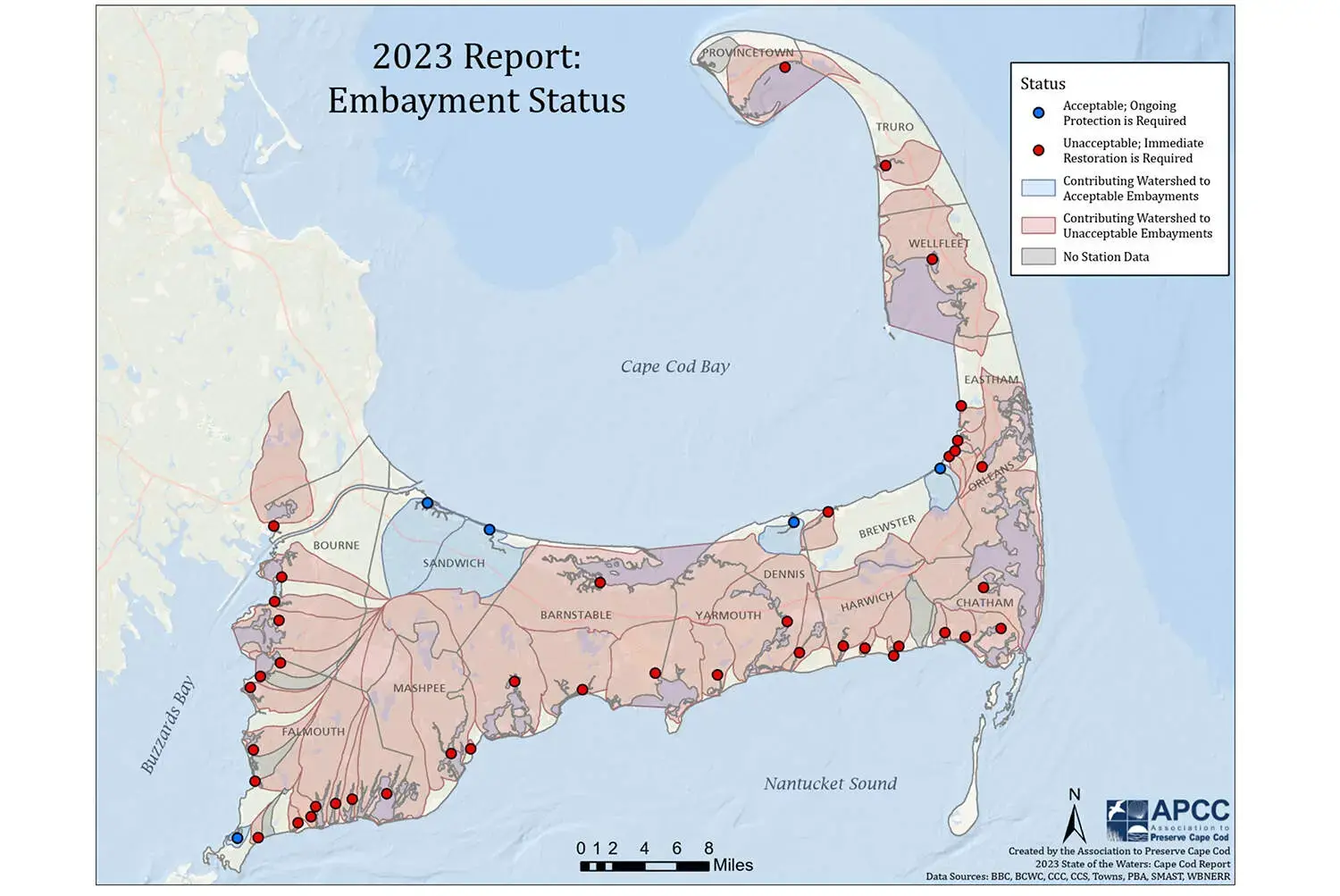

Uhlman’s pond did clear up that fall, but algal blooms are an ongoing problem on the Cape. Even the more common, nontoxic growths are destructive, creating low-oxygen dead zones that kill fish and native plants. Now, 90% of Cape Cod's coastal bays and more than a third of its ponds have "unacceptable" water quality, according to the nonprofit Association to Preserve Cape Cod's annual State of the Waters report.

"We've seen a significant deterioration of our bays to the point where they're designated as impaired, where we don't have shellfish, we don't have finfish," said Barnstable town manager Mark Ells.

The pollution comes primarily from septic systems, which leach nitrogen and phosphorus — basically fertilizer — in the Cape's groundwater. The state has tough new regulations that are forcing communities on the Cape to clean up the water. And towns are now grappling with the cleanup's enormous price tag: in Barnstable alone, cleanup will cost more than a billion dollars.

It's a critical moment for Cape Cod. The Cape has more than 550 miles of coastline, at least 890 freshwater ponds and 53 small saltwater bays bordering the ocean. That water is the Cape's raison d'être: residents and visitors use it for swimming, boating and fishing, and it forms the backbone of the region's $1.4 billion tourism industry. Now Cape Cod communities are scrambling for solutions before their ecosystems, economies and property values collapse.

"Most of our own personal financial wellbeing is intimately tied to the Cape continuing to be an attractive place to live. And so, as individuals we're all at an enormous risk," said Andrew Gottlieb, executive director of the Association to Preserve Cape Cod.

"People like Cape Cod and want to come to Cape Cod, and to a certain extent, they're loving it to death."

19th century technology

In the 1950s, Cape Cod was sleepy and semi-rural, with about 50,000 full-time residents. But the Cape's population boomed in the second half of the 20th century. Now there are about 230,000 year-round residents, and more than 5 million visitors during the summer.

All those people bring money, crowds and epic traffic jams. They also create something that most people don't think about: wastewater. About 85% of Cape Cod properties use septic systems to manage household waste, and experts say the technology is not up to the job.

"We rely on 19th century technology to get rid of our wastewater," said Gottlieb, who lives in Mashpee. "We all basically have a hole in the backyard and our wastewater flows into it."

The main component of a septic system is a large underground tank. Water from a home's sinks, washing machine and toilets flows into the tank and sits there. The solids sink to the bottom and the liquid percolates out into the ground. That nutrient-rich liquid flows quickly through the Cape's sandy soil to bays and ponds where it feeds the growth of invasive weeds and toxic algae. The process is amped up by climate change.

"What do you need to grow plants? Heat and water and nutrients. We've added the nutrients and we're turning up the heat," Gottlieb said. "So those two things have come together and are really causing problems."

Septic systems usually work fine in rural areas, where houses are spread out. In much of Cape Cod, that's no longer the case.

"We have a large population living here," said Ells. Barnstable is the Cape's commercial center and largest town, with about 50,000 year-round residents. The town's population triples in the summer.

Most experts agree that the best way to stop wastewater pollution in a big, densely packed town like Barnstable is to stop using septic tanks where possible and switch to sewage pipes — and that's what the town is doing. It has begun a massive expansion of the sewer system, extending service to 12,000 properties, building pump stations and upgrading its treatment plant. The project will take 30 years and cost an estimated $1.4 billion.

The price tags are high for smaller Cape Cod communities as well. The town of Orleans, for example, is building a new treatment plant for about $34 million and expanding sewer lines for millions of dollars more. Mashpee is spending $54 million on the first phase of its "clean water plan" to build a new treatment plant and wastewater collection system. It's unclear how much the full system will cost.

And there's another cost: seemingly non-stop construction on the Cape's already over-trafficked roads.

"A lot of people would say cost is the challenge, and it is a challenge," said Ells. "But the fact that construction is very disruptive is an enormous challenge as well."

Most Cape Cod towns only do roadwork in the shoulder seasons, to avoid disrupting summer tourist traffic. That means projects take longer to finish. Pat Uhlman’s neighborhood by Shubael Pond will get hooked up to Barnstable's sewer, but not for a couple decades. Uhlman says that’s too long to keep polluting the water.

"If we don't start cleaning it up now, you might not even want to walk down by that pond by then," she said.

A treatment system in your yard

A lot of Uhlman’s neighbors feel the same way. So instead of waiting decades for the sewer line, they’re getting new improved septic systems now. The systems are designed to remove nitrogen before it gets into the groundwater.

"This is really just a waste treatment system that's actually in the ground, in your house," said Zenas Crocker, executive director of the nonprofit Barnstable Clean Water Coalition. "This system is so successful that in the data that we're seeing now, it will remove between 95 and 97% of nitrogen going into the groundwater."

Crocker’s group has installed more than a dozen systems in Uhlman’s neighborhood as part of a pilot project to measure exactly how well the so-called "innovative/alternative" septic systems work. The systems installed in Uhlman's neighborhood are designed to work in conjunction with existing septic tanks, and they look pretty low tech. There's a cement tank the size of a minivan with two compartments, one filled with wood chips and the other with limestone rocks. Water flows from an existing septic tank into this one, where the rocks and wood chips create ideal conditions for bacteria that consume nitrogen, converting it to a harmless gas before it gets into the groundwater.

There are some drawbacks. There are many designs for advanced septic systems; some are unproven or may lose effectiveness over time. They also don't remove phosphorous or other contaminants like PFAS.

And these systems are expensive. Upgrading an existing system — like the installations in Uhlman's neighborhood — costs roughly $30,000. And completely replacing a traditional septic system for a single-family home with a nitrogen-filtering system could cost $35,000 or more, about twice as much as a traditional system. The Barnstable Clean Water Coalition raised money to install the systems by Shubael Pond at no cost to homeowners, but that's not an option for the whole Cape. Many residents have expressed concern about the cost and feasibility of the new regulations.

All Cape Cod communities with affected waterways have to clean up their wastewater under the new state regulations. Many communities are experimenting with low-cost solutions to curb nitrogen pollution, like oyster bed and cranberry bog restoration, which help filter nutrients out of groundwater; restrictions on using lawn fertilizer; and even urine diversion or "pee-cycling." But most experts believe that some combination of improved septic tanks and sewer systems will provide the bulk of the solution.

Brian Baumgaertel, director of the Massachusetts Alternative Septic System Test Center, said sewers are the “gold standard” for removing contaminants but aren't right for every community.

"Here on Cape Cod, we have areas that are dense where sewering would make sense because it's economical," he said. "And then we have vast swaths of Cape Cod that are so sparse in population — or even moderate density — where the cost of running sewering pipe down the road in all of those neighborhoods is incredibly cost-prohibitive."

Both improved septic tanks and sewer systems come with big price tags. There’s government money to subsidize both. But some costs will still fall on homeowners — probably in the range of tens of thousands of dollars.

"This is a really expensive process," said Uhlman. "But the Cape economy is still people coming here in the summer. If they can't swim in our ponds, they can't swim in our ocean, they can't boat, there's not going to be any reason for them to come here."

- View this story on Scientific American