SAVOONGA, Alaska – Derek Akeya hopes for calm waters and a lucrative catch when fishing from a skiff in the Bering Sea that surrounds his island village.

But on this windy late summer day, waves toss about the boat as Akeya stands in the bow, straining to pull up a line of herring-baited hooks from the rocky bottom.

Instead of bringing aboard halibut – worth more than $5 a pound back on shore – this string of gear yields four large but far less valuable Pacific cod, voracious bottom feeders whose numbers in recent years have exploded in these northern reaches.

“There’s a lot more of them now, and it’s more than a little bit irritating,” Akeya says.

The cod have surged here from the south amid climatic changes unfolding with stunning speed.

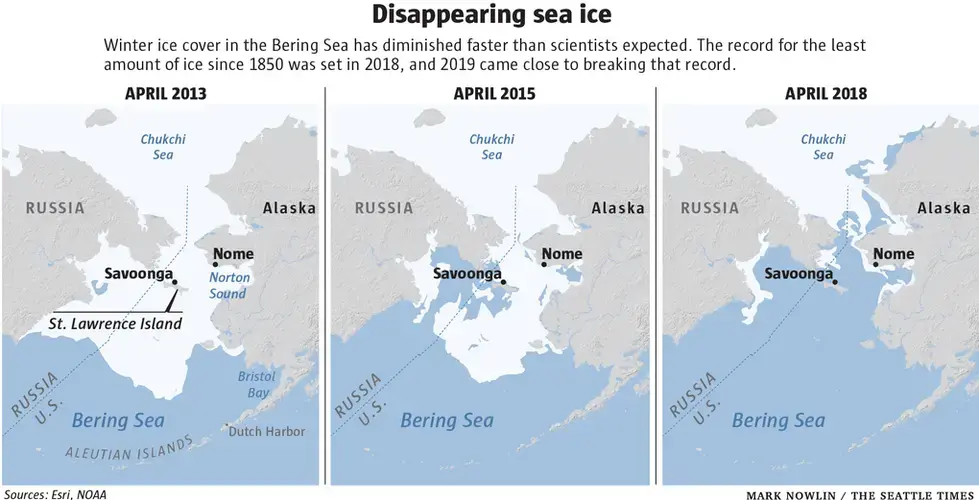

For two years, the Bering Sea has been largely without winter ice, a development scientists modeling the warming impacts of greenhouse-gas pollution from fossil fuels once forecast would not occur until 2050.

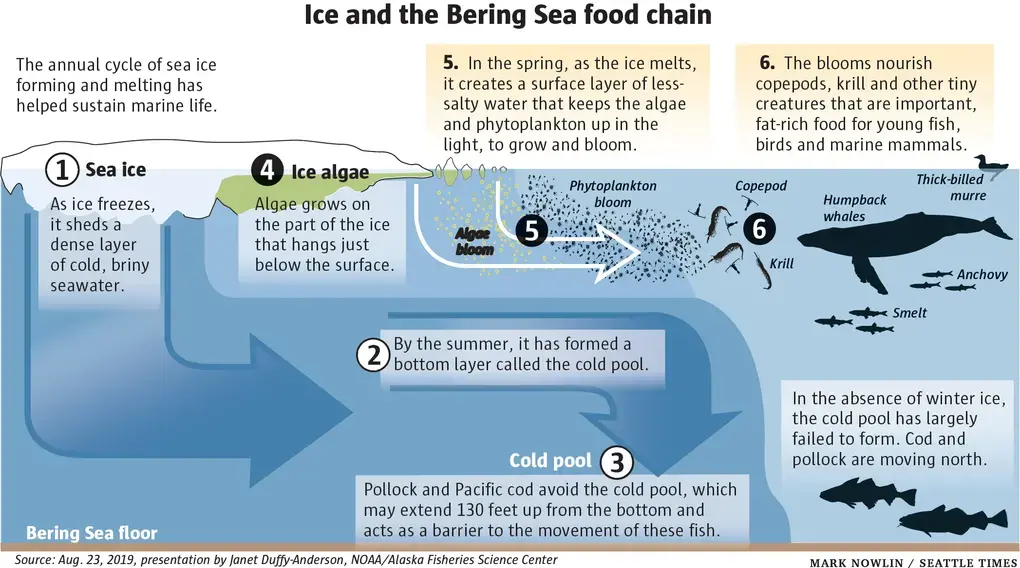

This ice provided a giant platform for growing algae at the base of the food chain, and has been a significant contributor to the remarkable productivity of a body of water, stretching from Alaska to northeast Russia, that sustains some of the biggest fisheries on the planet.

Much of U.S. seafood – ranging from fish sticks to king crab legs – comes from the Bering Sea, which generates income for an arc of communities that reaches from Savoonga to Seattle, where many of the boats that catch and process this bounty are home-ported.

For Native people such as Akeya, who is Yup’ik, the ice also has shaped their culture, helping them to hunt the walruses, whales, seals and other marine life that have long formed a crucial part of their diet.

Researchers now are uncertain when and to what extent the ice may return, and have scrambled to better understand the consequences of back-to-back years of its loss.

“There are very few places on the planet where environmental change is more apparent than Alaska,” said Robert Foy, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “When we talk about … sea ice, the changes we are seeing, they are on a massive scale.”

This summer, the pace of change also quickened on shore as a record-shattering heat wave contributed to the deaths of salmon before they could spawn, to wildfires that shrouded the city of Anchorage in smoke, and to the further melting of permafrost, which causes ground to shift and can create problems for buildings and roads.

Offshore, temperatures in some spots at the bottom of the northern Bering Sea this summer measured more than 12 degrees Fahrenheit higher than nine years earlier.

The warming supports the spread of toxic algae blooms, which have been found not only in the northern Bering Sea but in Arctic waters. Scientists aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy in August detected the toxins at surprisingly high levels in two spots in the Beaufort and Chukchi seas, raising concerns about the impacts on marine life.

The Bering Sea changes brought about by the lack of winter ice represent “the ecosystem of the future,” said Phyllis Stabeno, a Seattle-based oceanographer with the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory who has studied this body of water for 30 years. “As a scientist, I’m fascinated by it. But as a human being, I’m depressed.”

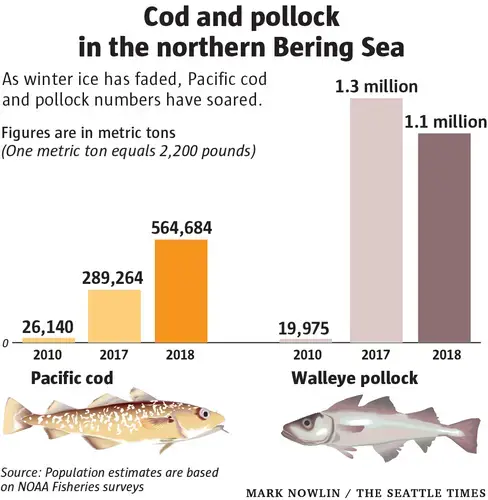

The northern Bering Sea now abounds with cod as well as pollock, two big-volume commercial species once largely found hundreds of miles to the south.

Meanwhile, halibut in these waters have declined, and smelts – an important food for seabirds – have crashed.

Some of the birds also appear to be struggling.

Emaciated murres and other seagoing species have washed onto the beach that fronts Savoonga and other western coastal villages. In Savoonga, residents also see fewer birds in a rocky island rookery near the village.

Savoonga’s location on St. Lawrence Island, midway between Russia and mainland Alaska, gives its population a ringside seat to the sweeping changes in the Bering Sea.

“Our cliffs are sick,” said Delbert Pungowiyi, president of the Native Village of Savoonga, a tribal organization.

A Break in the Food Chain

In harsh winters – full of winds from the north – the ice used to extend south from the Bering Strait almost to the Alaska Peninsula. Even in milder years, it typically stretched for hundreds of miles.

The ice froze through the fall and winter, shedding very cold, very briny seawater that – due to its density – would sink and eventually form a frigid layer down deep. Pollock, cod and many other species avoided the cold pool, and it often kept them from swimming north.

As the ice melted in the spring, it gave marine life a big boost.

Blooms of the ice algae — known as phytoplankton — spread through a less-salty band of water close to the surface, which also was rich in other forms of algae. All of this was a buffet for zooplankton, tiny creatures such as copepods and krill that are rich in fats and are key food sources for young fish, birds and some marine mammals.

When there’s no ice, there are still later blooms of phytoplankton. But they support less-fatty zooplankton.

“They’re … much smaller, not nearly as much bang for the buck, so the fish and seabirds are feeding on less-nutritious prey,” said Janet Duffy-Anderson, a federal research biologist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

The consequences for fish appear serious.

Duffy-Anderson was a part of a team that looked at pollock after a five-year stretch of ice-free winters in the southeast Bering Sea, ending in 2005. Young pollock had lower survival rates, and the adult pollock population later dropped by more than 40%.

The study, Duffy-Anderson said, raises the possibility that the entire Bering Sea — once it permanently loses winter ice — will sustain far fewer fish.

As the winter ice thinned and retreated, the cold pool shrank. The past two summers, it almost disappeared. Without that barrier, some fish are now migrating north and scattering across broader areas as they search for food.

Federal trawl surveys show huge shifts.

Since 2010, summer cod have increased more than 20-fold and pollock more than 50-fold in the shallow northern Bering Sea, which narrows where Asia and North America reach out toward one another.

Scientists are uncertain whether this area can support all these fish — over the long term — especially if the winter ice, and the algae that grows on it, fail to return.

But these fish seem to be on a long-term northern migration.

Overall, the center of the pollock population since 2012 has moved north an average of more than 18 miles a year.

“It is certainly one of the fastest (northward movements) I have heard of worldwide,” said Jim Thorson, an ecologist studying the loss of sea ice with NOAA Fisheries.

Skippers on the Front Lines

The owners of the Bering Sea fleets have billions of dollars invested. So far, though some are fishing farther north, overall harvests of nearly 4.4 billion pounds a year have remained relatively stable, producing fillets, fish burgers, surimi and other products for U.S. and global markets.

The Beauty Bay, a Seattle-based vessel that sets miles of hooks along sea-bottom lines, this summer sometimes caught more than 40,000 pounds of a cod a day — headed, gutted and frozen on board.

“The fish we are catching now are just beautiful. They are big and healthy,” said Scott Hanson, the boat’s co-owner and captain, during summer fishing that at one point took him into northern Bering Sea within 10 miles of St. Lawrence Island. The cod appeared to be finding plenty of food, including adult king crab, prickly shells and all.

“I’ve found their stomachs stuffed with hard-shelled crab legs,” said Hanson

Still, industry officials are closely monitoring the science and some are wary as fishermen notice disconcerting changes.

“Climate change is really in your face,” said Kevin Ganley, a Washington skipper with nearly 40 years’ experience fishing for pollock.

The ice melt in years past would help create big undersea bands — stretching for miles — of zooplankton, bait fish and other food that pollock like to eat. Ganley said he used to find these areas and drop his nets close by.

But these bands are “disappearing more and more,” Ganley said. “That’s a real concern.”

While some skippers this year report good pollock fishing, Ganley says it is often much harder to find them in big schools. So his boat, the 123-foot American Beauty, must sift through what he calls “micro-patches” of fish. And it may take 36 hours to fill the vessel’s enormous trawl net — six times longer than in decades past when Ganley found the pollock more bunched together.

This summer, much of the pollock catcher-processor fleet has been fishing farther to the northwest. They have congregated in an area near the international date line that divides the U.S. portion of the Bering Sea from that of Russia.

Some U.S. fishermen are afraid that if pollock continue to move in this direction, more will wind up on the other side of the maritime boundary. This will leave less for them to catch and more for the Russians, who have their own fleets of factory trawlers.

“There is certainly that potential,” said Alex De Robertis, a biologist with NOAA Fisheries in Seattle who this year set down four acoustic devices along the international date line to monitor the pollock’s cross-boundary movements.

Cod Where There Were Crab

For crab fishermen who live by the northern Bering Sea, the loss of ice appears to be upending their livelihoods. Most are based in Nome, which sprouted on the shore of the Bering Sea’s Norton Sound in the early 1900s, as news of gold found on the beach drew thousands of miners.

Small suction dredges continue to operate just offshore. Crabbers have made a living venturing onto the winter ice, where they cut holes to the water to catch king crab. In the open water of summer, they drop pots from more than 35 boats in harvests that in 2017 generated more than $2.5 million.

But this year has been disastrous.

Without the traditional covering of ice, winter was a bust.

During the summer, despite long offshore forays, crews failed to find much crab and fell far short of harvest limits.

“I typically have caught 23,000 pounds by now – but this summer, I have less than 5,000 pounds,” said Don Stiles, who fishes out of Nome on the 37-foot boat Golovin Bay.

Researchers say this scarcity could be because the crab — due to warming or other factors — moved out of their traditional harvest grounds, out of reach of the Nome fleet.

Some crab may have been eaten by cod that have moved in.

As Stiles and other skippers searched for king crab this summer, they pulled up pots that were sometimes filled with a dozen or more cod.

“That’s a lot of cod,” Stiles said. “You see it coming, and you think, ‘Oh, no.'”

In the middle of July, after pulling up several pots containing only cod and a few starfish, he got so discouraged that he opted not to retrieve more than three dozen other pots. In late August, he returned to check them.

Many pots held cod. And there wasn’t much adult crab.

A Tradition on the Ice

In Savoonga, the ice often held fast to the island shore deep into May, and the Yu’pik hunters used it to good advantage.

A pressure ridge of folded ice created a “perfect little hiding spot,” when hunting seals, wrote Denny Akeya, Derek’s father, in his book, “God Created Heaven and Earth, Including Me,” that documents the traditions of his people, Siberian Yu’pik, who share their culture and language with a Native people on the Russian side of the Bering Strait.

Though the ice could be an ally, it could also quickly turn deadly, if a hunter stepped in the wrong place, or got caught on a piece of ice drifting out to sea.

Denny Akeya, 68, taught his son Derek how to hunt on the ice during the later years of the last century, when winters packed enough of a punch to pile up ice around the village. Derek would help push boats across the ice as his father searched for patches of open water to hunt walrus and bearded seal.

Ice also made possible one of Derek’s cherished after-school pastimes. He would chop a hole, drop a line and catch fish to give to village elders.

Derek, now 31, once had doubts about staying in Savoonga.

After graduating from high school, Derek met Melanie Gustafson, a young woman from Minnesota who worked in Savoonga as part of Youth With a Mission, a Christian service group. They were married in 2010, and Derek moved for a few months to his wife’s small town of Alexandria, where the corn grew sweet and there were plenty of ripe summer tomatoes.

He missed Savoonga and the much more difficult food-gathering tasks that bound his people to the land and the sea.

“I just couldn’t do it — everything was just too easy,” Akeya said.

So the couple returned to start their family that now includes two young boys and a girl.

But with warmer winters, the shore-fast ice has been on a yearslong decline, and villagers have had a harder time hunting. Villagers hope each spring to land a bowhead whale, which are typically drawn to the island waters by the food they find at the edge of ice as it retreats. This year, Savoonga crews failed to land one.

In the summer, catching halibut offers a way to earn cash with fish that are cleaned and air-freighted to market.

But the halibut often are smaller than when the village’s commercial harvests began back in the 1990s.

On a good day, fishermen may still fill up their boats with more than 20 halibut, tossing over many of the cod to make room for the more valuable fish.

As Derek Akeya and two other villagers return from their late-summer fishing trip, they have just two halibut in their skiff as it pounds through the waves.

There is a slight chill to the air, a reminder that a change of season is not far away.

With the warm water temperatures of this summer, it will be harder for ice to form.

Still, climate change does not move in lock step from year to year, and scientists are unsure, in a time of such extreme changes, what happens next.

Akeya is not giving up hope that the coming winter will bring thick sea ice for his children to experience.

But he is not expecting a big turnaround.