As the year 2020 came to a close, Bangor Daily News reporter Callie Ferguson checked her email and discovered an attorney for the Maine State Police had sent more than 50 pages of trooper discipline records spanning the past five years.

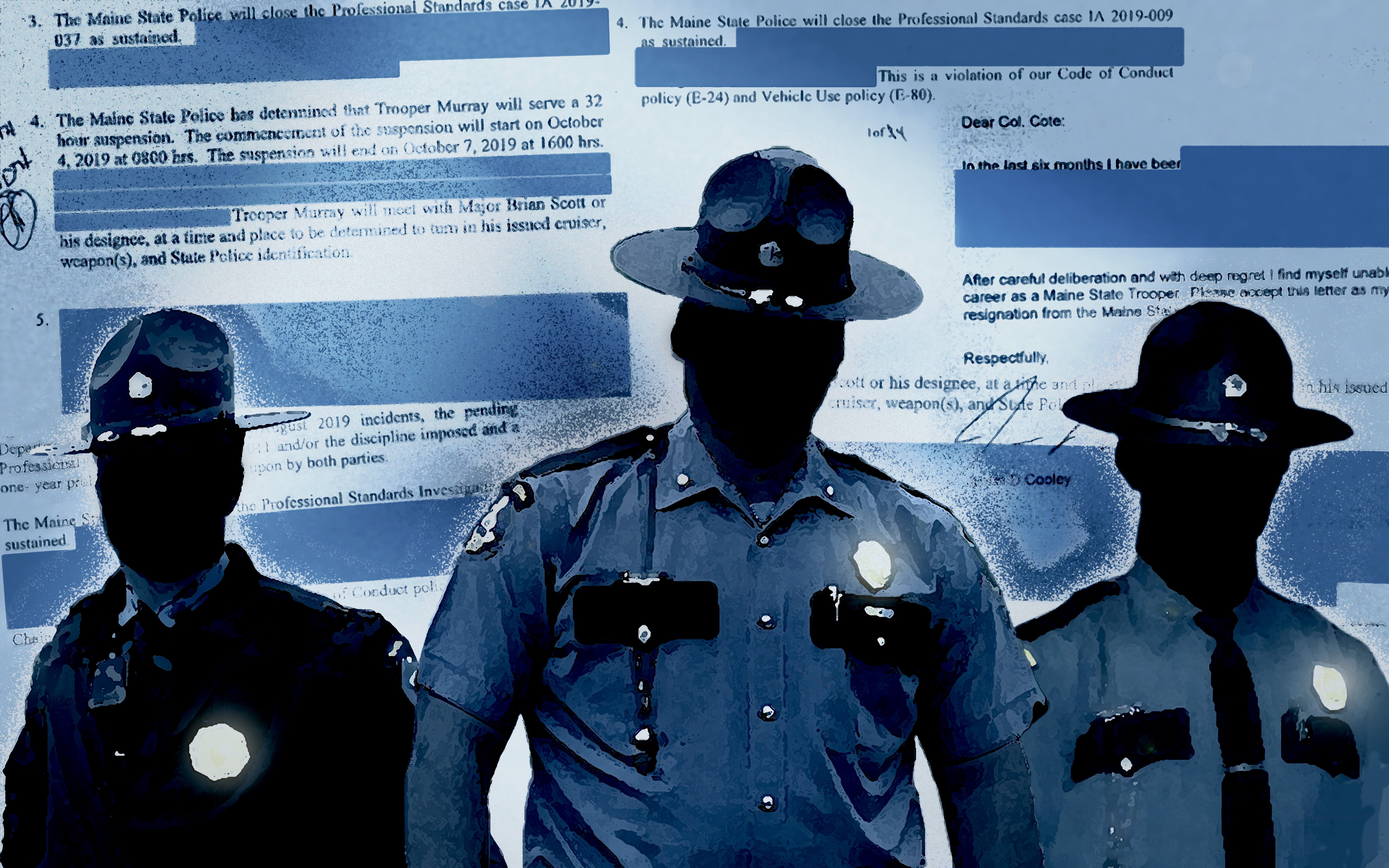

She had requested the documents six months earlier, in late May. Reading them, she wasn’t certain what they showed. The records were supposed to document when the agency punished officers for wrongdoing, but they were written in such a vague way that she couldn’t understand the underlying misconduct in most cases. In an email to her editor, Erin Rhoda, she also pointed out that the state police had “redacted portions of agreements that we could possibly contest.”

The next day, Dec. 30, 2020, Matt Byrne, a reporter for the Portland Press Herald, received a similar batch of discipline records. He had waited even longer than Ferguson, having requested them in February 2020 with the hope that they might serve as the basis for a story about how Maine’s largest police force handles discipline matters.

Instead, he sat in his living room and looked over the vague, blacked-out records with a similar frustration to Ferguson and Rhoda. Reporters usually ask for public records to answer questions. Instead, the records invited more of them: What misbehavior was the state police concealing? Why isn’t the agency more forthcoming, and what are the consequences of the lack of transparency?

It’s not typical for competing newspapers to team up. The public usually benefits from multiple news outlets competing on a single story because the competition results in more journalism.

In this case, however, Ferguson knew that Byrne had asked for similar records. Rhoda reached out to Cliff Schechtman, the Press Herald’s editor in chief, and, after a conversation over Zoom, everyone agreed that readers would ultimately get more information if the papers worked together to bring to light the misconduct missing from the records.

The partnership hopefully made a statement, too: that it was worth setting aside rivalry to better confront how police keep matters of public interest a secret.

The reporters received discipline records for 19 officers. For 12 of them, the documents lacked enough detail to understand what happened. The documents formed the basis of the investigation.

It’s difficult to begin a story with so little information, especially when all three reporters are working in separate locations from home. Some of the discipline records only had the names of officers, the date of the violation, their punishment and, sometimes, a brief description. There didn’t appear to be an obvious logic as to why some punishments were harsher than others. Byrne mentioned a trooper whose arrest he’d covered in the past didn’t appear to have a discipline record at all.

Rumors gave the reporters some leads. At least three former state troopers heard versions of why their former colleagues were punished. They decided to talk to Rhoda off the record because they thought the state police should be transparent about its mistakes. Some of them believed the agency let certain officers get away with lighter punishments than others.

But newspapers don’t publish rumors. Not unlike law enforcement officers, reporters look for evidence that can be verified. The reporters sought to confirm what they learned in a way that met standards for publication: by corroborating information with documents and on-the-record interviews.

Some of the records hinted at where to find additional information. In one case, Byrne studied a record stating that Trooper Bryan Creamer had been suspended for a day for failing to properly investigate a fatal motor vehicle crash on July 3, 2017, with few other details. But that date was a thread to pull. All fatal crashes result in reports stored with the Bureau of Highway Safety. How many fatal crashes could have happened on that day? Only one.

Byrne requested the report, and Rhoda saw the victim’s car had been registered to a woman who shared the deceased’s last name: Naomi Long. No one could find a current phone number for her, but Byrne found an email. Long wrote back to Rhoda within a few hours. By the end of the day, Rhoda had begun to unravel what had happened.

In other cases, the reporters pieced together an officer’s misconduct using public records from multiple sources. For instance, Detective David Coflesky was suspended for 60 days in 2016 for operating a motor vehicle “without permission” in Vermont after drinking alcohol. Ferguson cross referenced his name on a spreadsheet she keeps of Maine law enforcement officers who have been punished by the Maine Criminal Justice Academy, which certifies and decertifies officers, and found Coflesky among the names.

The academy provided her with the findings of its investigation, which contained a few more details: that Coflesky had been in Killington, Vermont; that he’d consumed “substantial quantities” of alcohol; and that the car he took belonged to someone else. Byrne called the police chief in Killington who confirmed the Maine officer was not arrested.

One discovery took Byrne in a direction he didn’t anticipate. Records from the criminal justice academy showed pending criminal charges against a state trooper, Justin “Jay” Cooley, but his name didn’t show up among the discipline records. Byrne spent a day in late January driving to the courts in Lewiston and Auburn to pull court documents related to the criminal charge and saw they contained Cooley’s ex-wife’s name. Byrne called her. It turned out Amy Burns had been waiting for several years to tell someone her story.

In this slow, tedious way the reporters gained momentum, with portraits of wrongdoing emerging through a collection of keyhole views. The time-consuming process illustrated the difficulty of getting answers to basic questions about how the state’s elite police agency holds its officers accountable.

The reporters also hit plenty of dead ends.

One record stated that Cpl. Tom Fiske had been reprimanded in July for being “engaged in misconduct” with a female passenger in his cruiser on the Baxter Park Road. Ferguson and Rhoda had independently heard more about what had happened through the rumor mill, but they struggled to confirm the truth with anyone with direct knowledge.

Rhoda checked three different dispatch systems to see if the misconduct had been reported to a 911 operator. It hadn’t. Ferguson wondered if the state police had discussed the situation over email, which is public, so she asked the state police to provide any such written exchanges. The agency denied the request, citing the statute that makes personnel records confidential.

Without more corroboration, Fiske’s transgression remains a rumor. But it’s noteworthy that information about misconduct still seeps out, just not through official channels where it’s been vetted.

Indeed, there were some questions that only the state police themselves could answer. But even when the agency didn’t use confidentiality statutes to block their way, the reporters often struggled to get complete responses.

For instance, in late January, Ferguson re-read each record and noticed details she hadn’t before. Not all of the records looked the same: Some were written in a memorandum format, while others read like a negotiated agreement between the agency and the officer’s union. Some troopers had multiple documents associated with a single punishment, while others had just one. Not all the records had signatures.

Christopher Parr, the agency’s staff attorney, is the state police’s point of contact for freedom of information requests. On Jan. 28, Ferguson emailed to ask if he could talk on the phone to explain the different records. He responded by saying he preferred to communicate via email “to ensure for the greatest transparency.”

Wanting to make sure Parr understood what she was asking, and that she’d have a chance to ask follow-up questions, Ferguson said it might be more efficient to talk on the phone and that he was welcome to record their phone call. Again he declined. She submitted 12 questions in writing the next morning. His reply took three weeks and didn’t address specific questions.

Earlier in January, Parr had mostly denied Rhoda’s request to lift the redactions from the documents the newspaper received. He also declined to specify the precise statutory reasons for each redaction.

So the BDN pursued its only other avenue for appeal. On Jan. 28, the newspaper filed a lawsuit contesting the redactions. The Press Herald then sued a month later, on Feb. 23. The newspapers have since combined their lawsuits, arguing that the state police unlawfully redacted information intended for public viewing. While Maine law makes most employee records confidential, records of final discipline are public.

Newspapers don’t often appeal denials of public information in court because it is expensive. But in this case, two outside organizations agreed to lend their support. The Washington D.C.-based Pulitzer Center provided funding to cover some of the attorneys’ fees, and Yale Law School’s Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic is working pro bono with the newspapers’ attorneys.

The lawsuit is ongoing.