This story excerpt was translated from Spanish. To read the original story in full, visit El País. You may also view the original story on the Rainforest Journalism Fund website. Our website is available in English, Spanish, bahasa Indonesia, French, and Portuguese.

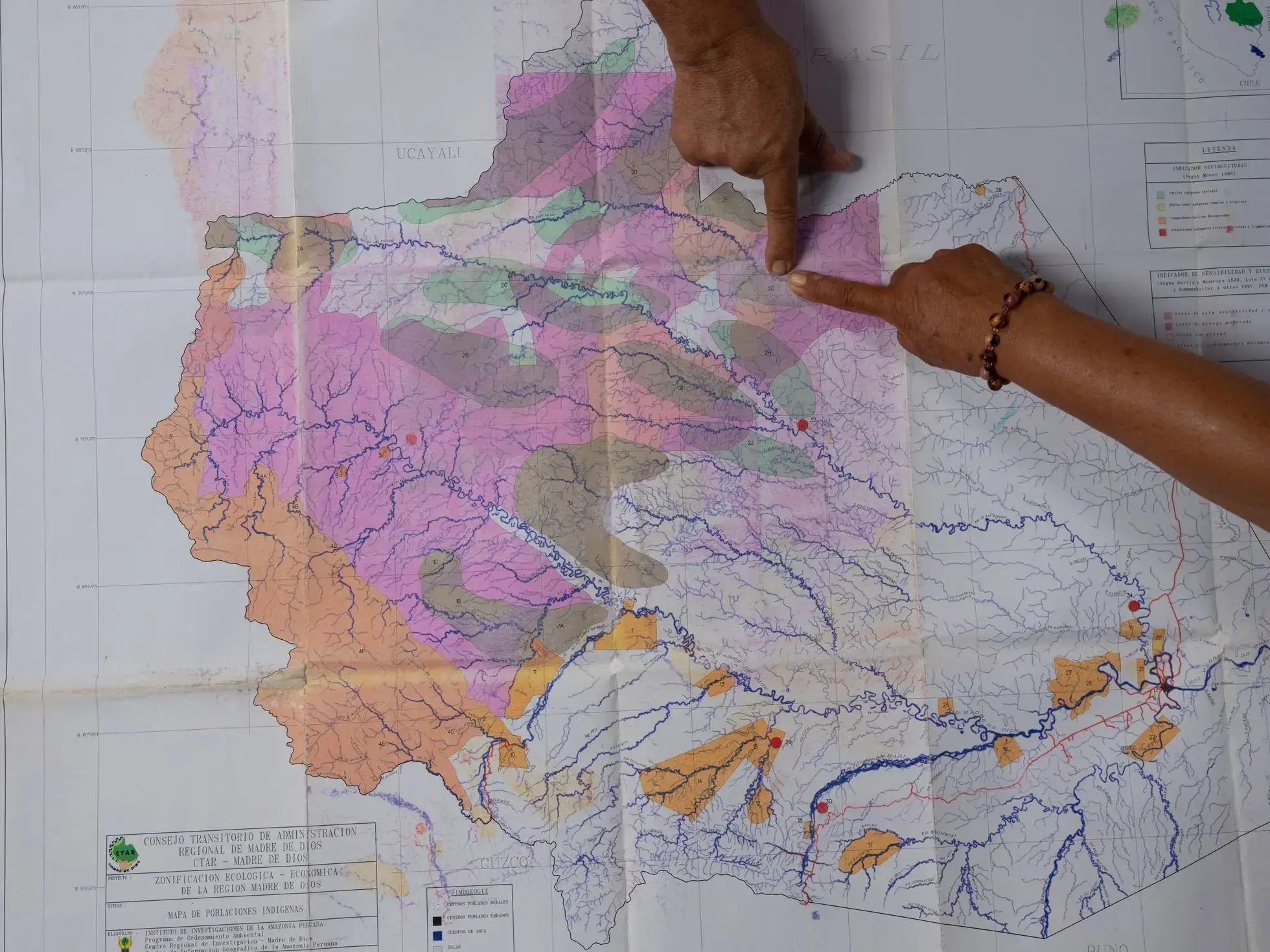

Campaigns to exploit the Peruvian Amazon threaten some of the last isolated groups on the planet. The struggle for territory and resources is now being fought in the courts and in the law offices. How to reconcile projects of 'national interest' with the survival of entire peoples and forests vital to the climate?

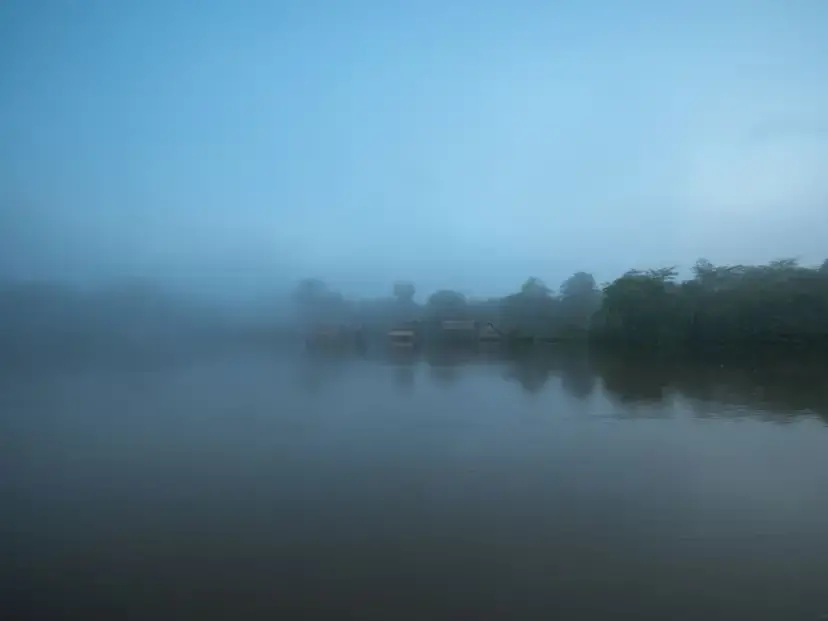

Deep in the Peruvian Amazon, on the border with Brazil, stands a small but fierce bastion of resistance to pressure from sectors such as oil and timber. The Matsés village of Puerto Alegre is a week's motorized canoe ride from the first town to handle money, but only a few hours from some of the last tribes in voluntary isolation on the planet; semi-nomadic groups who refuse contact with the outside world after being enslaved by rubber tappers last century, persecuted by settlers, decimated by imported ailments and bombed with napalm by the Peruvian Air Force in 1964 for opposing a road that was to cross their territory.

In Puerto Alegre, its inhabitants prepare potent ointments of frog venom for hunting, as well as access to satellite internet, weak, but enough to watch a few seconds of Bizarrap's Session 53 with Shakira. Chief Ricardo Nacua Pacha Moconoqui, 39, is the son of an Indigenous man who lived in isolation until his youth. Nacua knows how to handle a bow and arrow, but usually hunts with a shotgun. He also doesn't wear the traditional matsés tattoo - a line around the mouth connecting the corner of the mouth to the base of the ears - but displays a naïve jaguar tattoo on his shoulder. "Guerrero," he says. There is no state presence here, but there are many who try to enter to extract wealth. "If we don't defend this territory, who will?"

Unlike in most Native communities, the elders of Puerto Alegre preserve memories of their own life in isolation, when they shunned contact with the outside world. In the last two decades, the village they founded on a river overlook has driven out unscrupulous loggers, stopped a Canadian oil company in its tracks and contributed to the creation, in 2021, of an intangible reserve for Indigenous people who still remain isolated, and with whom they share territory. This advocacy has come at a cost for some Matsés. "I can't go anywhere alone," comments one of the activists behind the initiatives, who asks to protect his identity because he lives under threat. "People who used to be my friends became my enemies because they wanted to work for these companies."

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Despite the historic resistance of communities such as Puerto Alegre, the threats to them and their neighbors, the isolated peoples, are multiplying. For example, with a proposal to extract natural resources in protected areas, including those that are home to isolated tribes; a campaign financed by corporate lobbies to deny the documented existence of these groups; and state measures to expand fossil fuel extraction.