Last autumn, I spent a month documenting Canada's indigenous population. Originally, the story was supposed to examine HIV in First Nations communities. Canada's prevalence rates are 5 to 10 times higher than in comparable indigenous populations in Australia, New Zealand, or the United States, and the number of Aboriginal Canadians living with HIV increased by 24% between 2005 and 2010.

In a country that has one of the best healthcare systems in the world and pioneered some of the most progressive harm reduction strategies in existence, these numbers make no sense. To put them into context, a 2012 UNAIDS study shows that the number of new HIV infections in Sub-Saharan Africa decreased by 25 percent between 2001 and 2011.

Once I arrived and began to talk to subjects, a clear pattern emerged. Almost every indigenous person I met had ties to Canada's Indian Residential School system—a network of federally run, Christian boarding schools that were meant to assimilate young indigenous students into western Canadian culture. Until the last school closed in 1996, Indian Agents from the Department of Indian Affairs would forcibly take children from their reserves as young as two or three years old and send them to these places, where they were punished for speaking their native languages or observing any indigenous traditions. There are countless stories of sexual and physical abuse occurring as well, and in some extreme instances children endured medical experimentation and sterilization.

As a result, generations of Canada's First Nations forgot who they were. Languages died out, sacred ceremonies were simultaneously criminalized and suppressed by the Canadian government. "'You stupid Indian' were the first English words I ever learned," First Nations member Tom Janvier told me. He was sent to residential school as a three-year-old, where he was bullied, beaten, and sexually molested. "It became self-fulfilling. My identity was held against me."

As a way to cope, or to forget, or simply because any notion of self-esteem or self worth had been obliterated with their identities, a disproportionate number of First Nations people began to engage in high-risk behavior—which perhaps explains the elevated rates of HIV transmitted through injected drug use and unsafe sex.

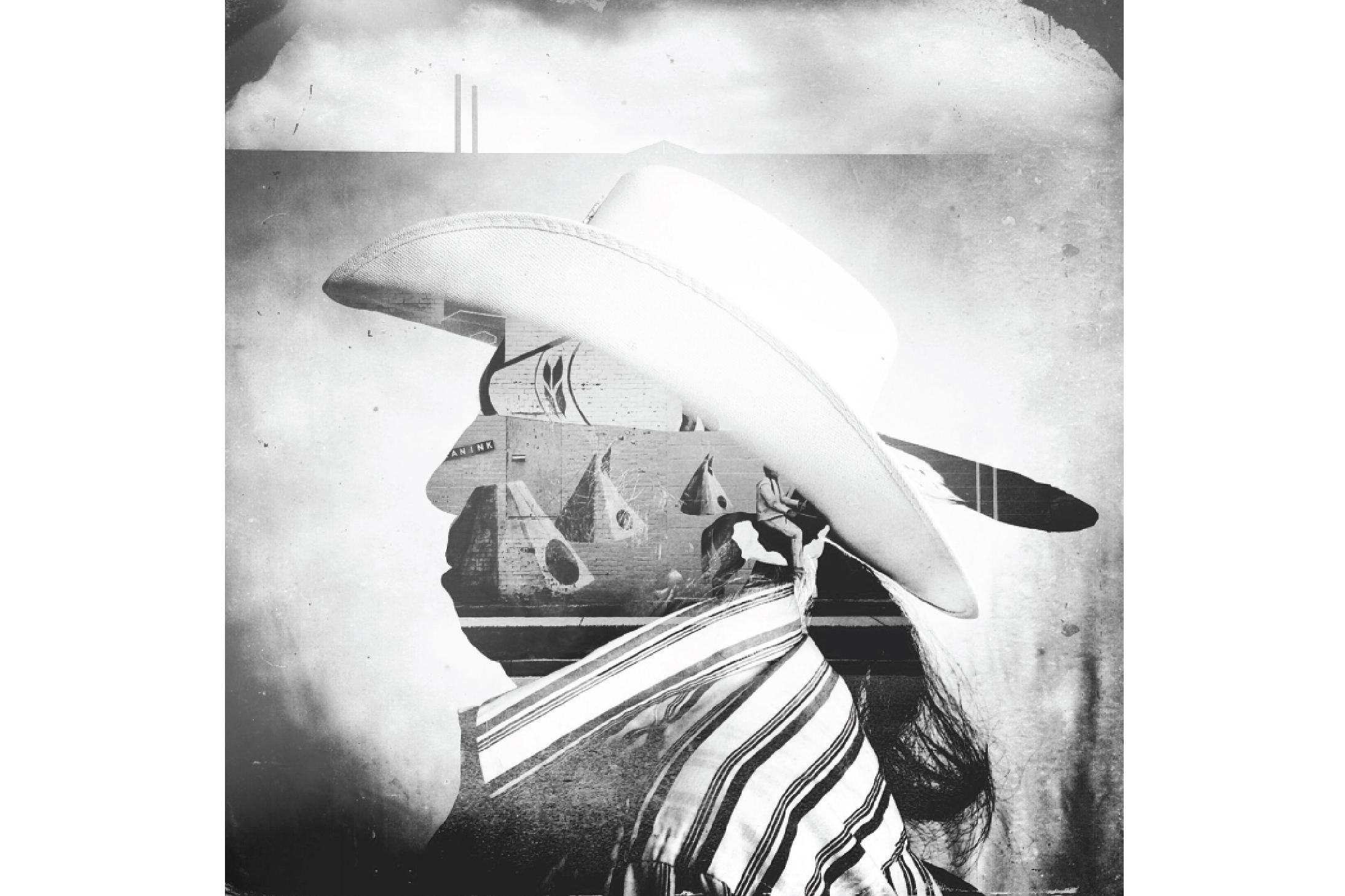

And yet, in spite of this system of institutionalized oppression, First Nations communities are finally beginning to recover. For the first time in decades, children are being brought up speaking Ojibwe and Cree and Blackfoot again. Potlatches and sun dances and sweat lodges have returned. As revealed in these images, made possible through a grant through The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, there is a new revitalization of First Nations culture occurring. Undeniably linked to the collective healing process, these people, who have endured so much, are reclaiming their voice in Canada.

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Brian Castner

The Mackenzie River in far northern Canada is the second longest in North America, a massive...