On a warm December day, Chrissy Beckles and two members of her team were calling quits on a day of searching for dogs at dumpsites in Yabacoa, Puerto Rico. Traveling down a crowded highway, Beckles spotted a black dot in an open field next to the road at a pincho (meat skewers) stand.

Slowing her car down, she scoured the field to identify it. Out of nowhere, there it was: a dog. It was moving through the scraggly field, likely following the enticing smells the pincho stand was emitting. Beckles and Sarai Cruz Negrón steered their cars off the road onto the gravel parking strip.

With the busy highway nearby, it could have been only a matter of minutes before the dog was injured, or worse, killed. This wasn’t the first time Beckles had placed herself in a tough situation, but it’s always for the benefit of Puerto Rico’s stray dogs.

Beckles, the founder of The SATO Project, first visited Puerto Rico over eight years ago. Her husband Bobby, a stuntman, was filming on the island, and she joined for the trip. After seeing the dogs that littered beaches during their visit, Beckles could not help but wonder what rescue groups were active and how she could help.

Compelled to do more after adopting her second dog, Boom Boom, Beckles began rescuing full time in 2009 and founded The SATO Project in November 2011. The SATO Project frequently works with other shelters and rescue groups, assists in adoptions, and hosts spay and neuter marathons.

With the early 2020 earthquakes in Puerto Rico, The SATO Project has been rushed to help evacuate dogs from the island. These included not only dogs they had rescued, but owner-surrendered dogs because of the natural disasters.

In the span of a month, they organized three chartered flights transporting over 250 animals to the United States for adoption. To put this in perspective, they usually average only five "freedom flights" per year.

These earthquakes are not the first natural disasters The SATO Project has been affected by. The most significant one was two years ago: Hurricane Maria. Beckles lost her home, and many volunteers and their families were directly affected as well. Hurricane Maria destroyed everything in its wake, and its lasting effects are still noticeable today, from areas of land stripped of trees to windows still boarded up with plywood.

“If you wanted to make a zombie apocalypse movie—this was the place. Everything was dead, but it’s astounding how fast it rebounded and regrew. But there are still, like the rainforest, parts that will never grow back,” Beckles said. It is astounding that they found dogs alive post-Maria; some were on the streets before the storm and some were abandoned because of it.

Dog overpopulation, animal abuse and cruelty are not issues that began in the wake of Hurricane Maria, with an earlier study showing connections between domestic violence and animal cruelty in Puerto Rico. “There’s never bad dogs, there’s bad people. It’s like having a kid, you have to raise them right,” Beckles said.

Leaving their vehicles, Beckles and Cruz Negrón formulated a plan to safely rescue the dog. Using the supplies stored in the back of Beckles’ black Jeep, Beckles approached the dog slowly with a plastic cup of hard dog food. Suspicious, the dog trotted around cautiously as Beckles lowered herself and the food closer to the dog’s level for its comfort. Sneaking closer to inspect the food, slowly the dog began to take some from her open hand. Cruz Negrón came up behind Beckles, leash in hand, and crouched down in the tall grass.

A few minutes passed like this, with Cruz Negrón and Beckles feeding the dog until it had achieved some level of comfort around them.

Beckles knew it was time to leash the dog before it bolted off. She placed her hand through the loosened leash, filled it with food, and waited until the dog began eating again to cautiously lift the leash over and around her neck.

All seemed calm until the leash tightened, and when it did, the dog panicked and began jerking herself away from Beckles in an attempt to flee.

Rescuing satos, the term given to the mixed-breed street dogs of Puerto Rico, is never an easy task. It often requires assessing the situation of the dog: are they in immediate danger from aggressive humans or busy infrastructure? If not, the long process begins with building trust. At one of the locations Beckles and her team visited earlier that day, a beachfront street, they encountered numerous dogs.

After placing food around for these skittish dogs to eat, she sent photos to one of her volunteer members, Daphne Osario, who quickly identified them as dogs she had been feeding for a few weeks.

This is the typical process of rescuing a sato; they spend weeks feeding them until the sato has built trust with the volunteer. This trust—likely the first positive interaction many of these dogs have had with humans—is vital in rescuing and rehabilitating dogs for adoption.

The dog bucked, frantically running and jumping back and forth. “Go grab a towel,” Beckles told Cruz Negrón.

Rushing back with the towel, Cruz Negrón gave it to Beckles who straddled the dog cautiously and wrapped it up in an attempt to calm it. With the dog under the control of Beckles, Cruz Negrón worked to wrap the remainder of the leash around its snout as a makeshift muzzle to protect from the possible bite out of fear.

With a frantic car swap, Henry Freidman began driving Cruz Negrón’s car as she climbed in the back of Beckles’ Jeep with the dog. Once everyone was loaded in, they headed off to Clinica Mi Mascota, an animal clinic frequently used by The SATO Project.

Once a dog is physically rescued off the streets, the real rescue process has only just begun. Upon arriving at an animal hospital, the sato undergoes numerous health checks such as tests for heartworms, or, if needed, x-rays. If the dog has a viral disease transmittable to other dogs, it is placed in quarantine. If it has a serious injury, such as one obtained by being hit by a car, it remains in the care of the animal hospital until healed.

Each dog can spend weeks in animal clinic care before it is placed in behavioral observation to see how they interact with humans and other animals. One place they can do this is at Osario’s home.

There, satos can develop in a safe space that has roaming land for them to play and interact with one another. Once it passes all health and behavioral checks, the dog is available for adoption. The process can take weeks to months, each time length depending on the individual dog.

Once arriving at Clinica Mi Mascota, Friedman and Cruz Negrón rushed inside with the newly rescued sato. Weaving through clinic visitors and their pets, they took the towel-wrapped dog back to a cramped x-ray room to test for heartworms immediately.

Heartworms are common in satos due to the tropical weather and high mosquito population in Puerto Rico. They constantly produce offspring, which is why it is important to notice it early, and cause inflammation and damage to the heart, arteries, and lungs.

Both sitting on the table holding the dog, Cruz Negrón softly petted the newly named Pinchata, a feminine riff off the word Pincho, to help her calm down. Minutes passed in the cramped examination room, where walls are lined with metal crates holding animals with differing injuries.

Beckles walked around, checking on dogs under her care and speaking with veterinary techs on their progress. Techs rushed back and forth through doors, sometimes holding animals and sometimes holding stacks of paperwork. Finally, a tech appeared and shared that Pinchata had tested negative for heartworm. The techs took her to continue running tests and doing health checks.

Walking up winding stairs to the upstairs of the clinic, Cruz Negrón, Beckles, and Friedman went to check on puppies rescued earlier in the day from a couple. The couple had noticed that one of the dogs wandering around their house had been impregnated by another street dog. Instead of ignoring her, they generously kept an eye on her and, when she delivered her puppies, they reached out to The SATO Project to come to rescue them.

They lived on a hillside house in close proximity to the earlier mentioned beachfront street. Upon arrival, Beckles and Osario, who had been initially contacted by the couple due to her work in the area, found a mom and four puppies ready for rescue. They loaded them into crates in Osario’s van and left for Clinica Mi Mascota. Seeing them later in the day, Beckles noted how much healthier they looked in just that short time of care.

In the wake of Hurricane Maria, The SATO Project was flying dogs out every week for the first few months. “We were the first plane into Puerto Rico other than military after Maria. We flew in human supplies and flew out dogs,” said pilot Ric Browde, President and CEO of Wings of Rescue, the flight organization that partners with The SATO Project for flying animals to the mainland.

American Airlines had ceased flights to New York, and overall the number of flights off the island significantly dropped. Beckles and her team began utilizing private flight groups, such as Wings of Rescue, due to their flexibility and absence of commercial airline restrictions.

These restrictions include temperature limits, where if the outside temperature was over 85 degrees, they could not fly. Because commercial airlines also often transport pharmaceuticals, pressurized cargo space is already taken and dogs are transported like regular cargo. Additionally, the financial difference was significant; flying 100 dogs on a private plane is cheaper than flying 100 on commercial.

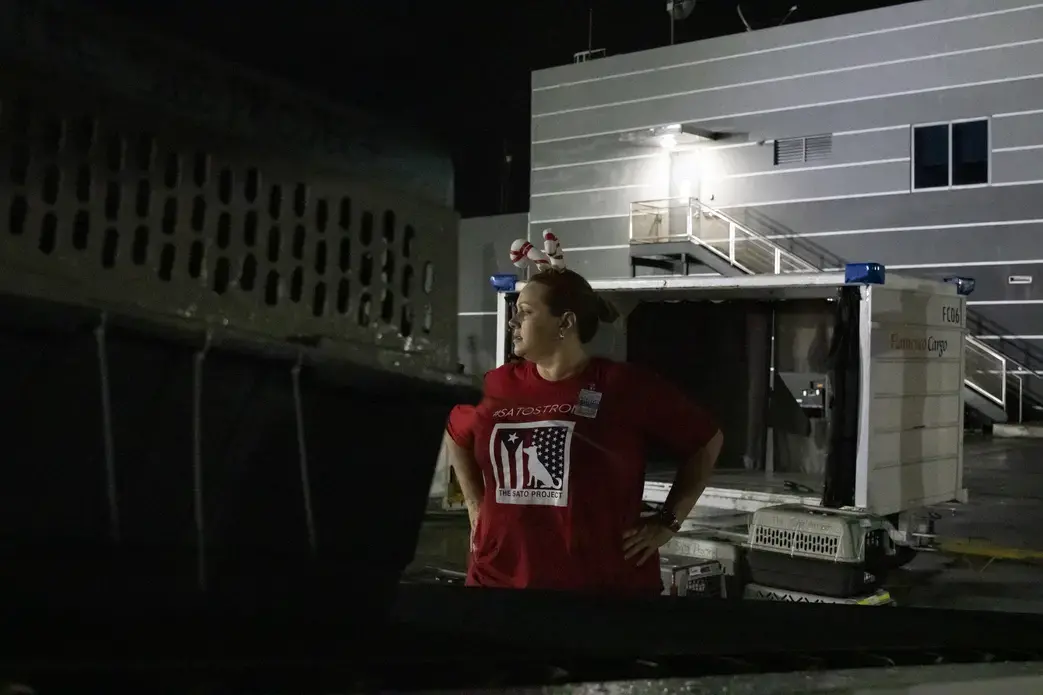

A typical freedom flight at night goes like this: around midnight, Beckles and her team head for the airport, surrounded by the active nightlife of Santurce and the probable ever-present drizzle of rain that defines Puerto Rico’s tropical weather.

As soon as they arrive, everyone hits the ground running. From midnight until 1 am, team members load and condense dogs into crates on a mobile cart train. On average there are two dogs per crate, as it is actually safer for the dogs to share space so as to not move around too much during turbulence.

The carts’ wheels begin turning around 2 am, bringing the dogs past the security gate and alongside the plane. As the clock strikes 2:30 am, crates begin the loading process onto the plane.

Like a giant game of Jenga, crates are organized by size and weight and Beckles calls out for specific numbers from the top of the conveyor belt.

The last crate hits the plane around 2:50 am; in those 20 minutes alone, around 50 crates are loaded onto the plane. Each dog is secure and ready for their freedom flight home. Once loaded, the plane moves to the end of the runway, waits for the signal, and takes off around 3 am.

Once the plane lands early the next morning in Morristown, New Jersey, families come to meet their dog, or individual volunteers drive them to their homes. On average 50 percent of dogs have homes and the other half are fostered. The average wait time in foster care is 10 days because they already have meet and greets lined up once the dog arrives.

Some people apply for a dog by name, seen on social media or the organization's website, or the team matches dogs to the adopters’ applications. It is a five-page application, suited to confirm a safe home and environment for the dog.

Some adopters’ applications stay in a database waiting for new dogs to be rescued and matched to them. The return rate is less than 0.1 percent, according to Beckles, and has only been returned on human error, for example an unforeseen circumstance like illness, not the dog’s. Over time, The SATO Project has experienced a high number of repeat adopters.

One of these adopters was waiting with open arms for Pinchata to come to her forever home on January 25, 2020. Pinchata was on one of the earthquake evacuation flights with five other lucky satos going to the continental United States.