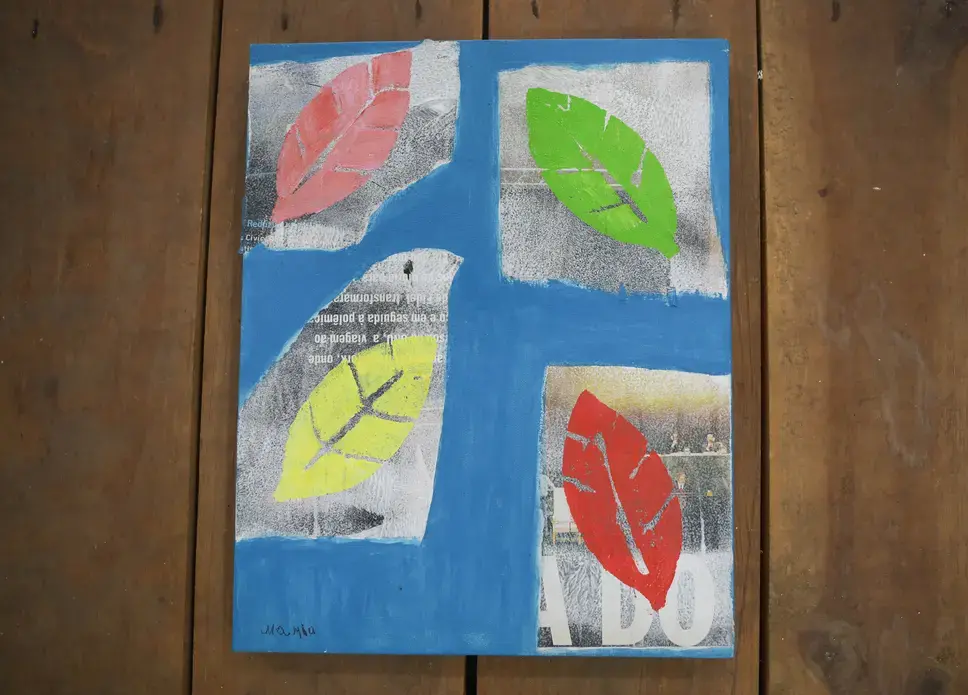

MARITUBA, Brazil — Art is Maria da Silva Trindade’s favorite class because, while she likes painting, she loves not having homework.

The 94-year-old hates homework.

Trindade is one of nearly 40 residents, most of whom didn’t graduate from elementary, still living in Marituba’s former leprosy colony. As of this school year, Trindade is the oldest student in a pilot program that is helping leprosy patients pursue their education.

“Before I got leprosy, I didn’t have the opportunity to study because I needed to work,” Trindade said. “I needed money for clothes, I needed money to live, so I went to work. But now, I can finally go to school.”

Brazil is the only country in the world still failing to reach the World Health Organization’s prevalence rate standard for leprosy elimination, which is one case per 10,000 people. Most recently, Brazil had a 1.48 case rate.

The northern state of Pará, home to Marituba, is one of the regions most affected by leprosy. Over the last quarter-century, the state has had more new cases than any other in the country. The Biblical disease, which passes through regular physical contact and respiratory droplets, is heavily stigmatized throughout Brazil.

Prior to the practice being outlawed, leprosy patients were federally-forced to relocate to colonies, like the one in Marituba. Trindade moved in after being diagnosed with the disease at the age of 15. In 2018, one in 10 people diagnosed with leprosy was under the age of 15, according to data from Brazil’s Ministry of Health.

“The women here welcomed me and gave me advice,” Trindade said. “They told me not to be afraid. They said one day I’d be healthy again and that I would do normal things, like go to school.”

Back to Class

Ediana Barbosa has been teaching Trindade and other Marituba residents since the inception of the pilot program.

“At first, I was a little afraid to work with older people because I am so much younger and they have so much more life experience,” Barbosa said. “But now, sometimes we forget the teacher-student relationship because we are more like close friends. We can talk about everything.”

To inspire others to join the free classes, Barbosa tells residents to look to Trindade. Despite the amputation of the majority of her fingers, Barbosa said Trindade is consistently one of the first students to arrive in class.

“She is a reference for other patients, we always say ‘If Maria can do it, so can I,’” Barbosa said. “She could just stay in her bed and watch TV, but she chooses to be here and to learn. She is an example for students and professors alike to never give up.”

According to Patricia Everdosa, the director of the former colony, interest in the program is slowly on the rise.

“The community has segregated them and has told them their whole lives what they can’t do—we are teaching them what they can do,” Everdosa said.

With more residents curious about class, Everdosa hopes to expand the program by offering a wider range of subjects and providing teachers with more supplies.

“We always ask them, ‘What do you want to learn tomorrow?’” Everdosa said. “We can offer them different types of stimulus that will allow them to live like people who don’t have leprosy. We want them to become the best versions of themselves.”