A century ago, at the end of the Great Influenza, global life expectancy was in the mid 30s. In the US, it was 47.

Today, just a hundred years later, global life expectancy is in the 70s. Childhood mortality worldwide has been reduced by a factor of 10. The doubling of human life expectancy should be understood as the single most important development of our era. If a newspaper came out only once a century, that extra lifespan would be the banner headline: world wars, moon landings, the Internet would all be below the fold.

But because doubling life expectancy happened slowly, the aggregate result of countless interventions, we don’t recognize it for the achievement it is. Far more people know about the moon landing than, say, the eradication of smallpox. That blind spot has consequences: think of all the Hollywood films, monuments, taxpayer dollars devoted to celebrating and supporting our military forces, and the tiny fraction of that money and attention devoted to the heroes of medicine and public health.

Doubling life expectancy is so momentous because it is so intimate and global at the same time: all those extra days of life you get to experience, the children you didn’t lose in infancy who get to grow old enough to have their own children. But the global effects are just as significant, and they create their own challenges. We added 5 billion humans to the planet since 1920, not because people were having more babies, but because we figured out all these new ways to keep people from dying. Global threats like climate change are also a byproduct of these public health and medical revolutions. If life expectancy had stayed where it was, atmospheric carbon levels would be much lower than they are today, because there would be far fewer humans living carbon-heavy industrial lifestyles.

And the COVID-19 pandemic — arriving right on the centennial of the end of the Great Influenza — is a reminder that continued progress in extending our lives is not inevitable. That’s why it’s essential to understand how we managed to pull off this extraordinary feat — and what we need to do to ensure the benefits of extended life are shared by all communities.

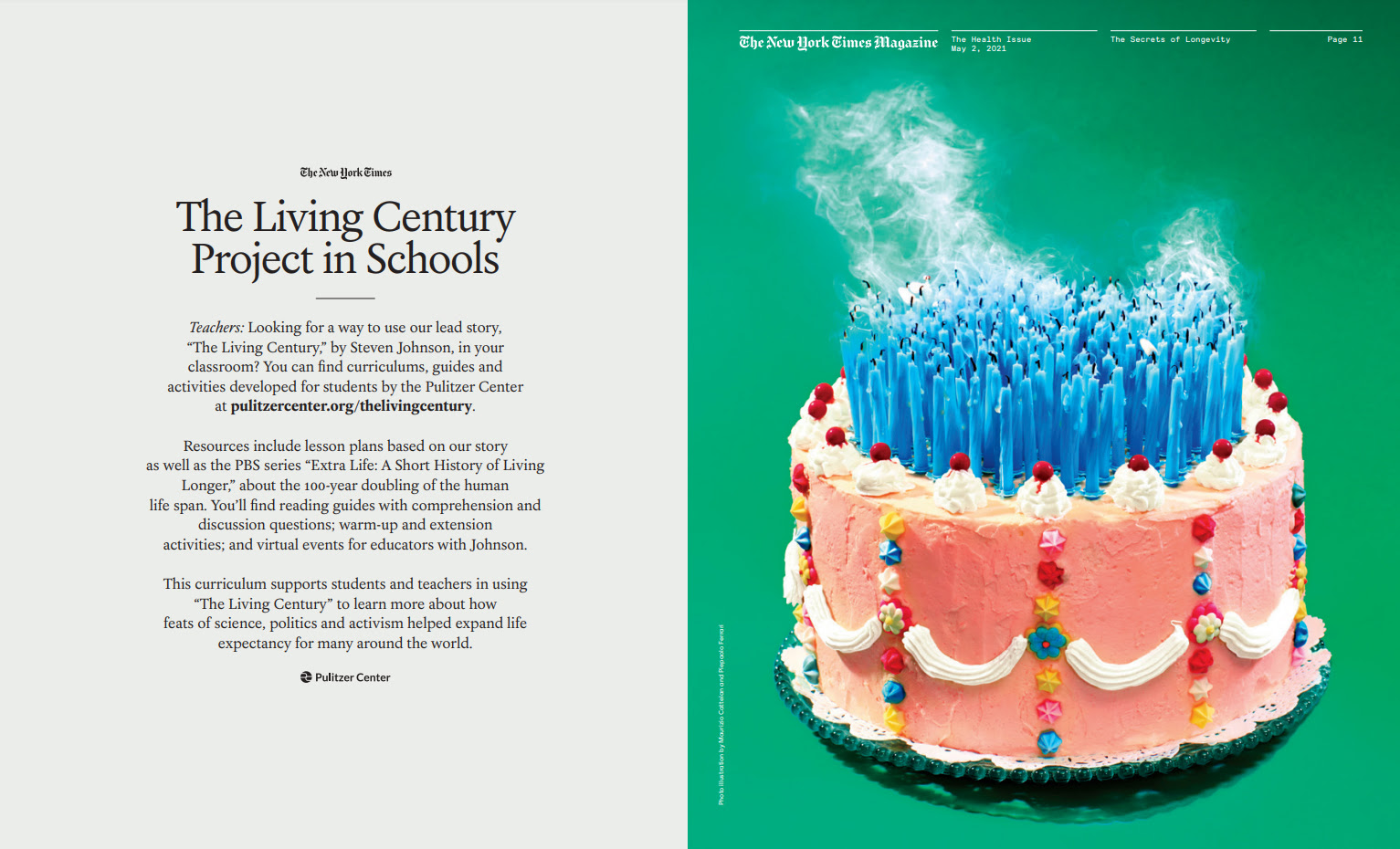

Pulitzer Center is proud to partner with The New York Times Magazine and PBS to create and share curricular resources connected to this project. Explore the curricular resources by visiting www.pulitzercenter.org/thelivingcentury.